Kaspersky, Argentina

With more than 2.5 billion gamers from all over the world, it’s no wonder that at least a fraction of them would bring into action additional tools to gain an unfair advantage over their opponents in the virtual world. This is one of the many reasons behind the existence and rapid growth of a multi‑million‑dollar industry that thrives on selling cheats, hacks and modifications to desperate gamers seeking to gain the upper hand in their next match.

Let’s dissect these tools and understand how modern games and anti-cheating technologies can easily be bypassed, all while we get a glimpse of the dubious market and supporting crews that develop, sell, and maintain the commodities in this illegal economy. It’s not unusual for cheats to be more expensive than the actual games they are trying to profit from, or for players to buy a single title over and over until they can avoid being banned by the protective measures implemented in the first place.

Fortnite? Overwatch? League of Legends? If you’ve heard of these games but you don’t know what an aimbot, a wallhack, or an ESP means, then you might finally understand why all those competitive matches you played have made you feel like a fish out of water.

Join me in this presentation and learn the inside-out of an industry that has remained in the shadows for a very long time. I will be presenting real-world cheats used by gamers worldwide that in some cases closely mimic techniques that would rival numerous advanced threat actors in the malware ecosystem.

Game over? Maybe not...

As of 2018, video games represent one of the most lucrative businesses in the world, generating US$43.4 billion in revenue within the United States alone [1]. Taking into consideration that video game licences are only a fraction of the total market, the importance of such an industry, when compared, for example, to the movie and music industry, is slowly becoming more evident. In addition, conservative estimates on the global revenue for the gaming industry indicate that it’s over US$130 billion for this past year [2], putting it above Hollywood and blockbuster releases premiering worldwide.

An entire ecosystem has been born around the gaming industry, eSports or electronic sports being one of the main attractions for audiences eager to watch teams or individuals play against each other in tournaments broadcast on cable television. With nearly 400 million viewers each year [3], and more being added via streaming platforms such as Twitch or Mixer, eSports and the mainstream media have found a balance between the two worlds, understanding that there’s an outstanding business potential in these competitions.

There’s an urban myth that video games are only played by a certain type of individual, but current research presented by ESA (the Entertainment Software Association) indicates that in the US the average gamer is 34 years old, and that women represent 45% of the gaming demographic. Currently, one of the leading factors when deciding which video game to purchase is the online gameplay capability, a feature that enables developers and publishers to charge a subscription fee for the service being provided, and provides players with a competitive arena in which to test their abilities against equally ranked opponents.

While difficult to understand for some, the popularity of video games is not an accident. Designers specifically craft rewards systems that keep the players hooked for long enough until they can receive the next ‘hit.’ Online worlds provide the novelty that humans seek, all within a controlled environment that anyone can join on demand. While the psychology involved in creating an addictive video game is outside the scope of this research, it’s important to understand why these virtual worlds present such a fragile equilibrium, where players who seek to gain unfair advantage over their opponents can easily break it.

Although the use of cheats in video games has been present since the early days of their development, it wasn’t until cheat codes appeared that they gained attention from enthusiasts wanting to make their gaming sessions easier or harder, depending on the cheat used. For example, a popular cheat named ‘Konami Code’, developed by Kazuhisa Hashimoto by porting the game Gradius to the NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) in 1986, is considered one of the first of its kind. This code enabled the developer to lower the game’s difficulty by giving the player additional resources, hence making the testing of the game much easier. It’s been a long journey since those days, and we can currently encounter cheats demonstrating malware-like behaviour, using anti‑detection techniques and evasion features that rival rootkits and implants found in advanced persistent threats.

This paper will address the following questions, inspired by the Five Ws [4] investigative methodology:

In the beginning it was common for games to be single-player, meaning that no one was affected by cheating other than the player controlling the game. In this context, cheating was used to modify game parameters and difficulty by abusing undocumented features or vulnerabilities found within the game. A clear example of this was cheat codes that game developers began embedding into their creations for debugging purposes. However, as time went by and the complexity of games increased, so did the complexity of cheats and the unforeseen consequences of this activity.

In today’s massive multiplayer and online context, cheating means that a player is able to gain unfair advantage over their opponents or the environment set up by the game developers. The reasons for using cheats in online games are various and so are the types of cheats available, depending on the type of game played. However, there’s a worrisome commonality that emerges as digital markets and communities demonstrate a marked growth year after year: game publishers invest large sums of money to create and maintain infrastructure for players to compete online, making these services available for a fee, yet cheaters spoil the fun for everyone, causing financial losses for the companies that can’t seem to put an end to this problem.

There’s an implicit equation that presents itself in trending video games, in which the player exchanges time either for an advancement of skills or ranking, or to amass virtual goods such as items that can be traded within the game or sold for a flat fee in different auction shops. If these players are legitimately paying for a game as well as a subscription service for online gameplay, and exchanging uncountable hours of their time in pursuit of a goal, it seems evident that cheaters are causing tangible losses by bending the rules that are set by the original game creators.

While different taxonomies exist for the classification of cheats [5], some more extensive than others, two noticeably separate categories surface when considering the nature of online video games:

Technical vulnerabilities are the primary focus of this research paper, paying special attention to the client and how different cheats take advantage of misplaced trust in the player’s environment. Multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) games like Dota 2 are mitigating these types of cheats by using a network architecture in which the server plays a significant role in deciding what the player sees and how the client interacts with the server and other competitors. However, this is not a common case given that other games prioritize speed and responsiveness over everything else [6], even at the cost of dealing with cheaters that can potentially harm the community, the game, and the company’s reputation.

The information security community has only recently begun to pay attention to the gaming industry and the problems that affect it, even though a lucrative and illegal business is growing at a steady pace and hiding in plain sight. There’s no need to look in anonymous or private networks to find stolen game items or compromised accounts markets; all it takes is a simple search and a bit of patience. When it comes to cheats, it’s astonishing to find that the same measures as are used to protect malware are used in these creations: packed or obfuscated code is the norm, all to protect intellectual property and avoid detection, just as in malicious code. Game publishers and anti-cheating solutions race to provide detection either by signature, heuristics, or even the reports of other players, giving the cheaters the upper hand by putting the industry in a reactive mode.

In the past, a grey market for stolen game items or credentials existed even on auction sites such as eBay. Nowadays, specialized virtual item websites have emerged as the answer to all those players looking to avoid putting in the effort or time required to level-up or obtain certain game items. An economy that includes virtual sweatshops in which someone else takes over the player’s account to perform dull or repetitive tasks in order to advance to a different level or acquire a particular skill is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to services offered to players wishing to avoid fair play rules.

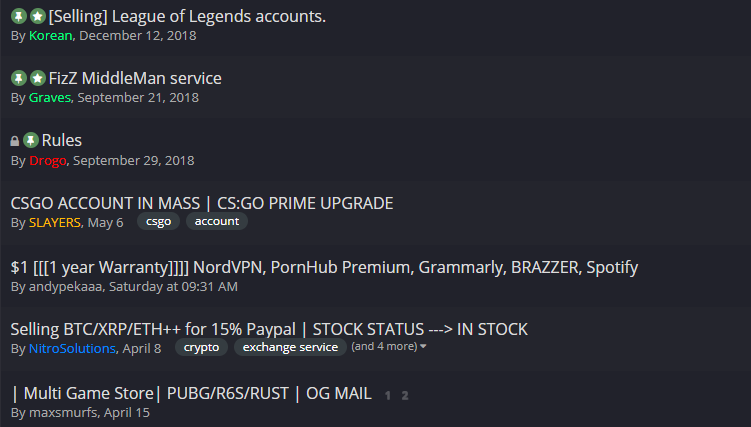

Figure 1: In addition to selling cheats, some online communities trade and resell hacked accounts for games, VPN providers and pornography websites.

While End User Licence Agreements (EULAs) clearly state that current games are licensed to the user and not sold, making the activities required to design and develop cheats illegal, websites such as UnKnoWnCheaTs or MultiPlayer Game Hacking (MPGH) provide cheat programming tutorials in different languages along with ready-made cheats shared by community members, all in a free manner. Even if public cheats, such as the ones found on these websites, are short-lived and players using them are usually banned promptly, they serve as a starting point for those that are eager to develop and expand their private collection of cheats. The longevity of these sites is evidence of their popularity among gamers: ‘UnKnoWnCheaTs is the oldest game cheating community in existence – we have been leading the game hacking scene for over 15 years...’ [7] Even if companies are fighting a battle against cheaters, some players evidently prefer to use them and claim that it’s their legitimate right to do so as buyers and enthusiasts of the games.

One of the most infamous cheats that gave a few indicators of the magnitude of the returns obtained by cheat developers was WoWGlider, a bot developed by MDY Industries for World of Warcraft, a game which at its peak gathered 12 million players together in a virtual world. WoWGlider sold over 100,000 copies for US$25 each, making this single cheat a multi-million-dollar enterprise. However, it gained so much attention that Blizzard Entertainment, the developer of World of Warcraft, sued MDY Industries and ordered it to pay US$ six million under allegations of copyright infringement.

Other cases related to companies tracking down cheaters and cheat developers are more subtle, such as the case of game developer Realtime Worlds, which decided to offer a ‘cheater amnesty’ [8] by allowing them to come clean before being banned. By the company’s estimates, almost 50% of the banned accounts were paid accounts, and some had over 1,500 hours of gameplay on them. Moreover, the company estimated that ‘the revenue that the three main cheat-makers had been generating was between $15,000 and $50,000 per month each, with users spending $30 per month on hacks.’ [9].

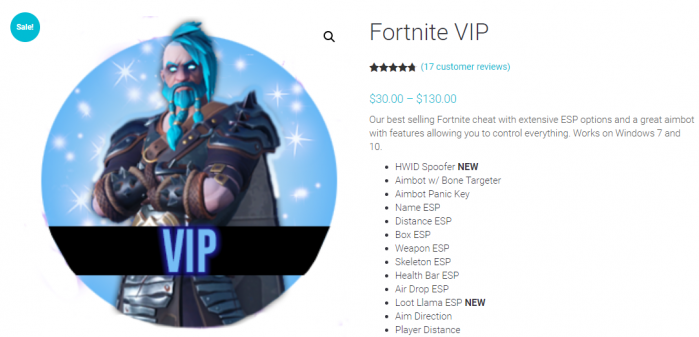

Figure 2: Depending on the game and how customized the cheat is, the price could easily exceed the original cost of the game.

As with ransomware, sometimes fighting cheat developers using legal resources means a long and tedious process in which different laws are involved, since the author might have one nationality but host the cheat in a different country, and finally distribute it to different regions again. In an example of the ‘Napster Effect’, even if the result is successful for the game publisher, nothing stops other individuals carrying the torch and taking it from where the last developer left off, promptly replacing one cheat with another, newer one. Furthermore, chasing cheaters means turning against users that pay for the game and an online subscription fee, creating a dilemma that some companies prefer simply to ignore.

During January 2019, Valve Corporation, the creator of the digital distribution platform Steam and popular games such as Counter Strike, Dota 2 and others, banned over one million accounts in what is known as the biggest ban wave to hit Steam so far [10]. The exact date on which these accounts were marked for banning is still unknown, as it’s a common procedure to delay the verdict in order to avoid giving out information about which cheats have been detected or when.

Maintaining a clean gaming community is paramount in these days of online multiplayer games where the life expectancy of a game is dictated not only by its graphics, music, or the level of entertainment provided in single-player mode, but by the hours of endless fun that players can access via competitive matches against other players. Let’s take, for example, the first-person shooter (FPS) Counter Strike, released in 1999 and still played worldwide and updated with different editions such as Counter Strike: Global Offensive. Another interesting example is the real-time strategy (RTS) game StarCraft, initially released in 1998, and presenting a sequel in 2010: StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty. Both games are still played competitively to this day for prizes that average half a million dollars per tournament [11].

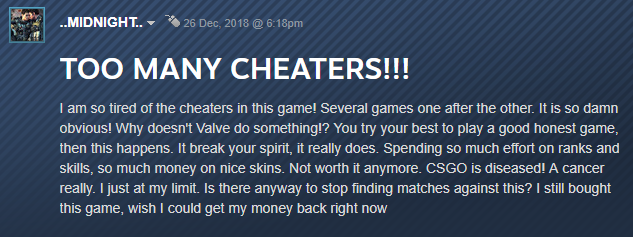

Figure 3: Communities are riddled with messages complaining about the number of cheaters increasing and ruining the game for players and the reputation of the developers [12].

Figure 3: Communities are riddled with messages complaining about the number of cheaters increasing and ruining the game for players and the reputation of the developers [12].

Valve’s digital download market and community registered 125 million users as of 2018, remaining the dominant PC games distribution platform. Steam offers publishers and developers a straightforward and familiar environment for monetizing their creations. However, blockbuster games such as Epic Games’ Fortnite, Blizzard’s Starcraft and Riot Games’ League of Legends choose not to be a part of Steam and control their own ecosystems. Perhaps Steam’s 30% cut is more than enough reason to drive the big-name publishers to develop their own in-house solutions and infrastructure for each title.

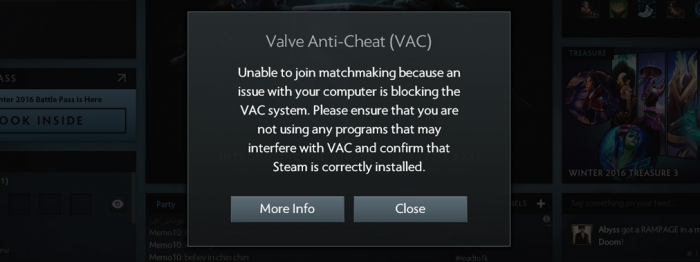

One of the features that has kept Steam as the leading platform for online gaming is the VAC system, where VAC stands for Valve Anti-Cheat, an ‘automated system designed to detect cheats installed on users’ computers. If a user connects to a VAC-Secured server from a computer with identifiable cheats installed, the VAC system will ban the user from playing that game on VAC-Secured servers in the future.’ [13].

Initially, the VAC system banned players for only 24 hours, then for longer periods such as one to five years, and currently a ban is permanent and non-negotiable, as explicitly stated by Valve. Even if new accounts are easy to obtain, unless the user provides some form of verifiable information such as a credit card or a phone number, the platform’s functionality will be greatly reduced. While cheating cannot be avoided entirely, it can be made expensive for those trying to engage in the activity.

The way anti-cheating engines work remains unclear, as security through obscurity appears to be an essential component to keep cheaters in the dark about how detection is being achieved. There’s a heated discussion between end-users and publishers protecting their communities with this type of software, as privacy concerns keep reaching the media. Even doing a simple web search caused some anti-cheating solutions to incorrectly prohibit players from joining a game, as memory scans detected words such as ‘cheat’ and flagged the suspicious activity. Valve’s VAC has had its own fair share of accusations for inspecting DNS queries made by the user, even prior to launching any game from the platform [14]. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has classified Blizzard’s anti-cheating component ‘The Warden’ as spyware, given that most users are unaware of this piece of code inspecting their network traffic and filesystem, even if they previously agreed to having it installed in the EULA [15].

The methods used by anti-cheating solutions for protecting players include full memory scanning, process analysis, code inspection, and more. As presented in the previous section, users have raised concerns over privacy issues mostly because they are unaware that these components are active or of how much of their information is being sent back to third-party companies. In order to detect cheats, these tools require user-level or kernel-level privileges, constantly looking for matched patterns previously defined in signatures, exhibiting similar behaviour to traditional anti-virus software.

When considering the network architecture of online games, some elements have to be handled by the client to speed up processing and reduce the lag between when an action is sent to the server and when a response is received and rendered on the display. This leaves the door open to client-side cheating, where the player can modify game files, memory variables, or even use different graphic card drivers to reveal information that was previously hidden by the game client. Such is the case with wallhack or ESP (extra sensory perception) cheats, in which the player is able to see opponents through walls, exhibiting god-like abilities simply by having more information to hand than other players.

Figure 4: A wallhack and aimbot from a cheat provider that sells time-based subscriptions for different games. A monthly subscription can start at around US$20, rising to US$100 for a lifetime membership.

Figure 4: A wallhack and aimbot from a cheat provider that sells time-based subscriptions for different games. A monthly subscription can start at around US$20, rising to US$100 for a lifetime membership.

A popular tool used for debugging games and beginning the development process of a game modification is Cheat Engine [16], which includes a hexadecimal editor, memory scanner, and a graphical user interface that makes the task of reverse engineering games much simpler. While Cheat Engine is aimed at single-player games, as we have seen earlier, sometimes all the player needs is additional information that the game already possesses but has chosen to hide while participating in multiplayer matches.

As is the case with some malware families, techniques such as code injection are not uncommon when it comes to modifying the behaviour of video games. To achieve this, cheat developers can use Cheat Engine to analyse and mark the desired memory regions or memory variables to modify, mapping the usually obfuscated game functions and understanding how to run their custom code on demand. Since operating system protections such as Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) and Data Execution Prevention (DEP) add complexity to this task, developers rely on professional debuggers such as IDA Pro or Olly Debugger to create signatures [17] that can identify a code section that is able to change its memory address each time it its executed.

Figure 5: VAC will monitor running software and if it detects PowerShell, Sandboxie, Cheat Engine, or other blacklisted utilities it will prohibit the player from joining an online match [18].

Figure 5: VAC will monitor running software and if it detects PowerShell, Sandboxie, Cheat Engine, or other blacklisted utilities it will prohibit the player from joining an online match [18].

Function hooking is used by advanced malware implants and rootkits, intercepting function calls in order to modify the behaviour of particular software or even the operating system. This technique also proves useful in cheat development as it provides a way to render objects that are hidden from the player or add scripted events when distinct conditions occur. With the use of function hooking and basic knowledge of a scripting language, it’s trivial to write a simple program (bot) that can automate boring or tedious tasks and execute tasks repeatedly at a speed that no human would be able to match.

Fortnite, a battle royale style game with over 250 million players [19], will detect the presence of a running debugger when the game is launched and attempt to thwart reverse engineering activities, warning the user about it. More advanced cheaters have gone one step further in their objective of gaining an unfair advantage over their opponents and are using rootkits that are able to hide game modifications from anti-cheating utilities. This creates a dynamic threat landscape in which game developers need to have anti-cheating solutions to protect their games, and these solutions could also exhibit rootkit behaviour. It’s an arms race between two opposing forces, ironically, as it is with many current video games.

The activity of cheating in video games covers a wide spectrum of activities and motivations. A growing economy is thriving in a niche market, targeting those individuals that are looking to pay for utilities, hacks, trainers, and different modifications that can alter the game’s difficulty at will. Their behaviour is sometimes internally justified when the cheating is done only to ‘beat the system,’ and not other human players. While the social and behavioural ramifications of cheating other players would require a different type of study, its consequences are evident and have a direct impact on the revenue of legitimate companies and honest players.

Monetary estimates of the size of this virtual economy are problematic, as the aforementioned cases that have been legally prosecuted end up revealing only a modest glimpse of this landscape. In spite of this, given the astonishing userbase of AAA games, it’s possible to speculate that the problem is much bigger than is currently represented by a handful of examples. The information security community is beginning to take a more proactive approach when it comes to protecting gamers, and educating them about the dangers of online entertainment activities.

As an emerging research area, it’s paramount that security professionals are equipped with the necessary knowledge that allows them to monitor these grey markets and these dubious tools that mirror the behaviour of traditional malware infecting users worldwide. This is a puzzle that requires a multidisciplinary approach in order to provide companies and users the fair play environment they envisioned when developing or purchasing a game. Perhaps a game developer is not familiar with the terminology and intricacies of the malicious landscape security professionals deal with on a daily basis. In the same manner, a vast majority of reverse engineers wouldn’t necessarily know the meaning of an aimbot, wallhack, or ESP.

The level of engagement and interest a user will demonstrate in a game, although variable, is not random. Extensive studies on the functioning of variable rewards systems measure how often a player should receive some form of stimulus from the game. As with the now moderately infamous ‘Skinner Box’ [20], video games use the same principles for creating compelling and addictive environments that players can’t resist. Considerable effort goes into designing levels, characters, and a reward system that will keep players on the edge of their seats for uncountable hours. However, when cheaters are factored into this delicate equation, we can begin to observe how the activity interferes with the level of enjoyment other players experience, thus converting the game into an activity that’s not fun anymore. And when players stop playing, and online communities become toxic, a whole industry, and the jobs that depend on it, suffer.

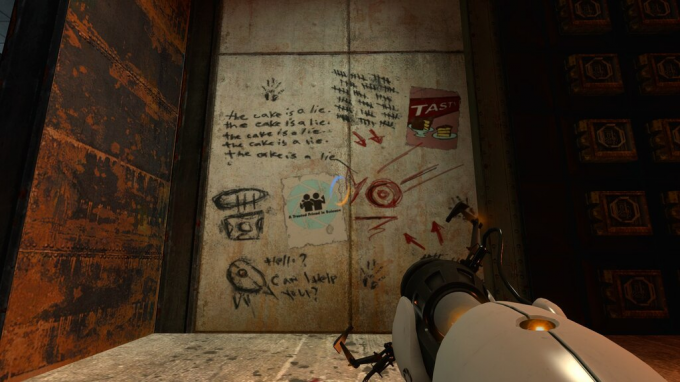

Figure 6: ‘The cake is a lie.’ In the game Portal 2, an Easter egg shows that the promised reward sometimes is only used as a motivation and is not real. The essence of behavioural game design distilled in a simple phrase.

As old as mankind, cheating is not a novel activity per se, but adding the technology component produces an attractive scheme in which to study and understand the consequences of this behaviour on a massive scale. With malware-like abilities, a wide range of utilities for game modification are distributed and sold each day. The anti-virus industry already has experience in dealing with obfuscated code, packed executables, and other common techniques found in malicious samples that can easily be transferred to the gaming ecosystem. Even if not all cheats are created equal or are malicious in their nature, the illegality of these creations is clear, and that’s not taking into consideration the security and privacy implications for users.

[1] U.S. Video Game Sales Reach Record-Breaking $43.4 Billion in 2018. http://www.theesa.com/article/u-s-video-game-sales-reach-record-breaking-43-4-billion-2018/.

[2] Market Brief – 2018 Digital Games & Interactive Entertainment Industry Year In Review. https://www.superdataresearch.com/market-data/market-brief-year-in-review/.

[3] eSports is now an industry with 400 million viewers. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audio/2019-02-14/esports-is-now-an-industry-with-400-million-viewers-radio.

[4] Five Ws. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_Ws.

[5] Jianxin Yan, J., Randell, B.:, A systematic classification of cheating in online games, 2005. https://prof-jeffyan.github.io/acm_ng05.pdf.

[6] Source Multiplayer Networking. https://developer.valvesoftware.com/wiki/Source_Multiplayer_Networking.

[7] UnKnoWnCheaTs - Multiplayer Game Hacks and Cheats. https://www.unknowncheats.me/forum/index.php.

[8] Do we need some sort of ‘cheater amnesty’ as we crack down on cheaters? https://bandedehoufs.net/BDHapbnotespatchs2011_09.html.

[9] APB Reloaded cracks down on cheaters. https://www.engadget.com/2011/10/02/apb-reloaded-cracks-down-on-cheaters/.

[10] Over 1 million VAC banned in January. https://www.esports.com/news/over-1-million-vac-banned.

[11] StarCraft II Esports in 2019. https://wcs.starcraft2.com/en-us/news/22820917/StarCraft-II-Esports-in-2019/.

[12] Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. https://steamcommunity.com/app/730/discussions/0/1742229167202400143/.

[13] Valve Anti-Cheat System (VAC). https://support.steampowered.com/kb/7849-RADZ-6869.

[14] Valve DNS privacy flap exposes the murky world of cheat prevention. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2014/02/valve-dns-privacy-flap-exposes-the-murky-world-of-cheat-prevention/.

[15] A New Gaming Feature: Spyware. https://www.eff.org/es/deeplinks/2005/10/new-gaming-feature-spyware.

[16] Cheat Engine. https://www.cheatengine.org/aboutce.php.

[17] SigMaker. https://github.com/ajkhoury/SigMaker-x64.

[18] Disconnected by VAC: You cannot play on secure servers. https://support.steampowered.com/kb_article.php?ref=2117-ILZV-2837.

[19] Fortnite Usage and Revenue Statistics (2018). http://www.businessofapps.com/data/fortnite-statistics/.

[20] The psychology of rewards in games. http://www.mostdangerousgamedesign.com/2013/08/the-psychology-of-rewards-in-games.html.