Fortinet, Canada

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

Andromeda, also known as Gamaru and Wauchos, is a modular and HTTP-based botnet that was discovered in late 2011. From that point on, it managed to survive and continue hardening by evolving in different ways. In particular, the complexity of its loader and AV evasion methods increased repeatedly, and C&C communication changed between the different versions as well.

We deal with versions of this threat on a daily basis and we have collected a number of different variants. The botnet first came onto our tracking radar at version 2.06, and we have tracked the versions since then. In this paper we will describe the evolution of Andromeda from version 2.06 to 2.10 and demonstrate both how it has improved its loader to evade automatic analysis/detection and how the payload varies among the different versions.

This article could also be seen as a way to say 'goodbye' to the botnet: a takedown effort, followed by the arrest of the suspected botnet owner in December 2017, may mean we have seen the last of the botnet that has plagued Internet users for more than half a decade.

The first Andromeda to be discovered was spotted in the wild in 2011, and the new 2.06 version followed quickly afterwards in early 2012. Not much is known about any earlier versions and it is possible they were never released into the wild.

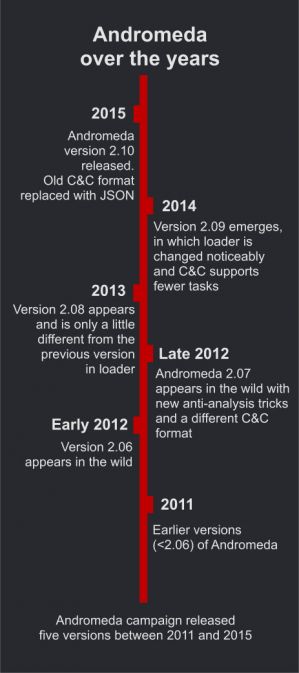

The campaign continued to develop with versions 2.07, 2.08, 2.09 and 2.10. The latest known version, 2.10, was first seen in 2015 and may be the final version released: according to posts on underground forums, the development of the threat stopped around a year ago. Figure 1 shows a brief history of Andromeda.

Figure 1: A brief history of Andromeda.

Regardless of the version, Andromeda arrives on the target machine as a packed sample. Various packers have been used, from very famous packers such as UPX and SFX RAR to lesser known and even customized ones which are compiled in various languages such as Autoit, .Net and C++.

Unpacking the first layer of the sample reveals the loader, which is small both in terms of size (13KB to 20KB) and in the number of function calls it contains.

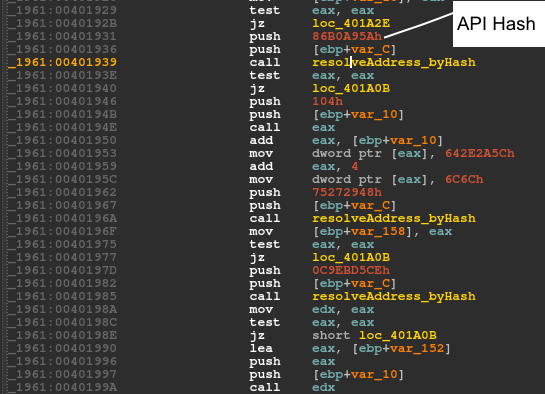

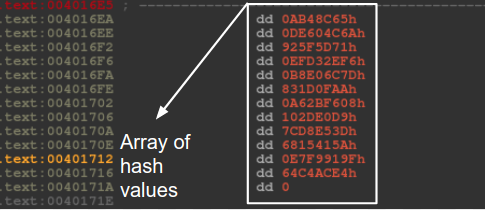

In all versions of Andromeda the loader avoids making direct calls to APIs. Instead, it incorporates hashes to find and call the APIs via general purpose registers. Versions 2.06, 2.07 and 2.08 pass hash values as immediate values to a function and thus find the matching API name. Version 2.06 uses a custom hash function, while versions 2.07 and 2.08 use CRC32. Versions 2.09 and 2.10 have the same trivial custom hash function. Figure 3 shows the loader in version 2.09 handling an array of hash values.

Figure 2: Version 2.08 passes the hash as an immediate value to 'resolveAddress_byHash'.

Figure 2: Version 2.08 passes the hash as an immediate value to 'resolveAddress_byHash'.

Figure 3: In version 2.09, the loader handles an array of hash values.

Figure 3: In version 2.09, the loader handles an array of hash values.

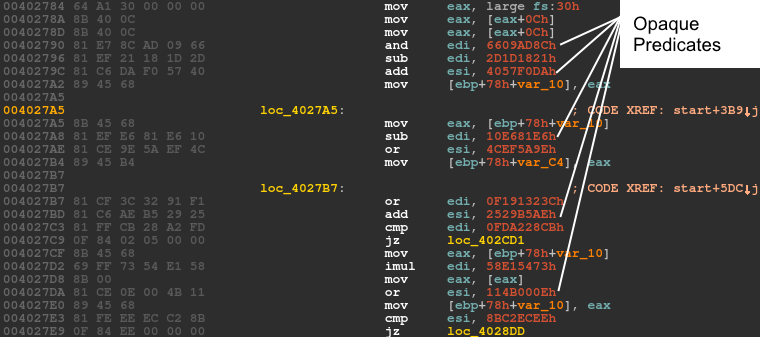

Version 2.10 also keeps an array of API hash values. The hash algorithm is a custom function and, in order to complicate static analysis further, the author incorporates opaque predicates, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Opaque predicates in the version 2.10 loader make static anaylsis more difficult.

Figure 4: Opaque predicates in the version 2.10 loader make static anaylsis more difficult.

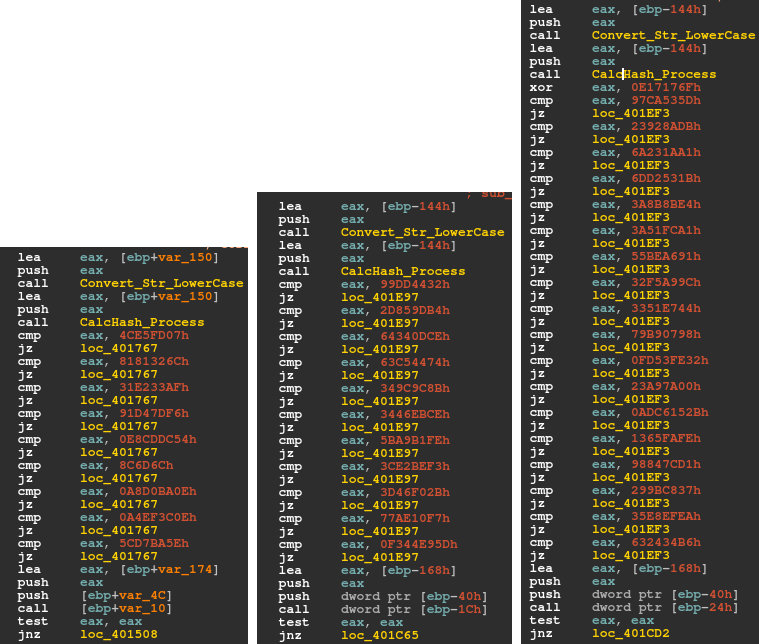

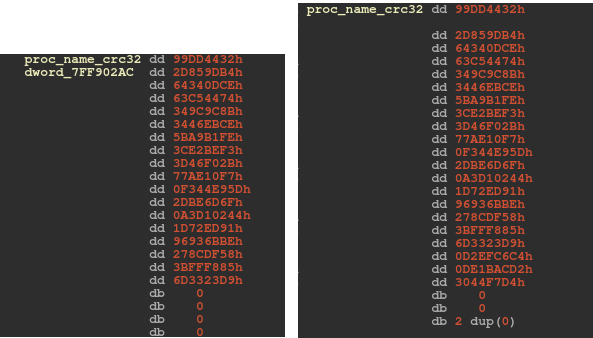

The section in the loader that is used to evade virtual machines and, more generally, analysis, is similar in versions 2.06, 2.07 and 2.08. In these variants, the loader enumerates the processes running on the machine and compares them against a list of unwanted processes. In order to do this, the loader converts the name of each process to lowercase and then calculates its hash value. The hash values are then compared against a hard-coded list of values. The same algorithm as is used to hash API names is used here. The hash algorithm in version 2.08 has an extra xor instruction (xor eax, 0E17176Fh). As shown in Figure 5, the newer versions have longer lists of unwanted processes.

Figure 5: From left to right: version 2.06, 2.07 and 2.08 hard-coded hash values correspond to the list of unwanted processes.

Figure 5: From left to right: version 2.06, 2.07 and 2.08 hard-coded hash values correspond to the list of unwanted processes.

| 2.06 | 2.07 | 2.08 |

| 0x4CE5FD07: vmwareuser.exe 0x8181326C: vmwareservice.exe 0x31E233AF: vboxservice.exe 0x91D47DF6: vboxtray.exe 0xE8CDDC54: sandboxiedcomlaunch.exe 0x8C6D6C: sandboxierpcss.exe 0x0A8D0BA0E: procmon.exe 0x0A4EF3C0E: wireshark.exe 0x5CD7BA5E: netmon.exe |

0x99DD4432: vmwareuser.exe 0x2D859DB4: vmwareservice.exe 0x64340DCE: vboxservice.exe 0x63C54474: vboxtray.exe 0x349C9C8B: sandboxiedcomlaunch.exe 0x3446EBCE: sandboxierpcss.exe 0x5BA9B1FE: procmon.exe 0x3CE2BEF3: regmon.exe 0x3D46F02B: filemon.exe 0x77AE10F7: wireshark.exe 0x0F344E95D: netmon.exe |

0x97CA535D: vmwareuser.exe 0x23928ADB: vmwareservice.exe 0x6A231AA1: vboxservice.exe 0x6DD2531B: vboxtray.exe 0x3A8B8BE4: sandboxiedcomlaunch.exe 0x3A51FCA1: sandoxierpcss.exe 0x55BEA691: procmon.exe 0x32F5A99C: regmon.exe 0x3351E744: filemon.exe 0x79B90798: wireshark.exe 0x0FD53FE32: netmon.exe 0x23A97A00: prl_tools_service.exe 0x0ADC6152B: prl_tools.exe 0x1365FAFE: prl_cc.exe 0x98847CD1: sharedintapp.exe 0x299BC837: vmtoolsd.exe 0x35E8EFEA: vmsrvc.exe 0x632434B6: vmusrvc.exe |

Table 1: Corresponding process to each hash.

Next, the bot takes advantage of registry artifacts and checks the registry value in the following key:

Key: HKLM\system\currentcontrolset\services\disk\enum

ValueName: 0

Version 2.06 parses the value of the subkey for the presence of the substrings 'qemu', 'vbox' and 'wmwa'. Similarly, versions 2.07 and 2.08 check for 'qemu', 'vbox' and 'vmwa'. (It is likely that 'wmwa' was a bug in version 2.06 that was patched later.) Upon finding any of these strings, each version takes a different approach to redirect the flow of the code.

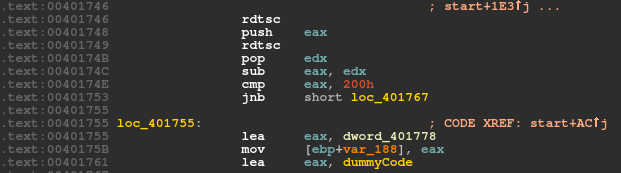

Before redirecting the code in versions 2.06 and 2.07, the sample designates another snippet of code that uses a technique known as 'time attack' in order to prevent further analysis. The malware acquires the timestamp counter (by calling rdtsc) twice and calculates the difference between the two. If the difference is less than 512ms, it proceeds to resolve imports and decrypt the payload. Otherwise, it leads to a dummy code, where the loader drops a copy of itself in %ALLUSERSPROFILE% and renames it to svchost.exe.

Figure 6: Timestamp analysis to detect the debugger.

Figure 6: Timestamp analysis to detect the debugger.

Following that, it creates an autorun registry for the dropped file as follows:

Key: HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

ValueName: SunJavaUpdateSched

Eventually, waiting for a command in an infinite loop, it sniffs port 8000. A received command will then be run in the command window.

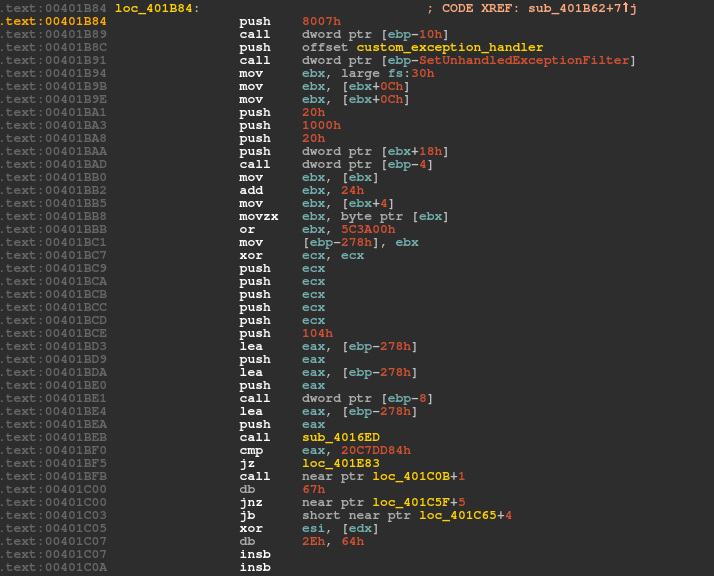

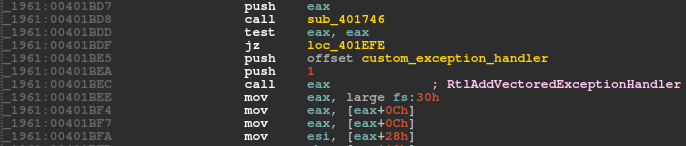

As part of its evolution, version 2.07 implements a custom exception handler using a call to SetUnhandledExceptionFilter. Similarly, version 2.08 calls RtlAddVectoredExceptionHandler and adds the custom handler as the first handler into the vectored exception handler chain (VEH), as shown in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7: Bot creates a custom exception handler in version 2.07.

Figure 7: Bot creates a custom exception handler in version 2.07.

Figure 8: Bot adds a custom exception handler into VEH in version 2.08.

Figure 8: Bot adds a custom exception handler into VEH in version 2.08.

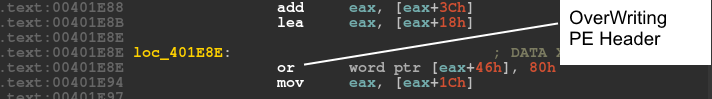

If the malware finds any of the substrings in the retrieved registry, it runs a function that causes an access violation. The access violation is created intentionally when the sample tries to overwrite the DLL characteristics in the PE header which only has read rights, as shown in Figures 9 and 10.

Figure 9: Overwriting the PE header raises an exception.

Figure 9: Overwriting the PE header raises an exception.

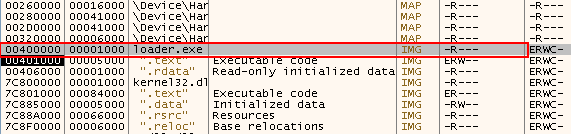

Figure 10: The PE header only has read rights.

Figure 10: The PE header only has read rights.

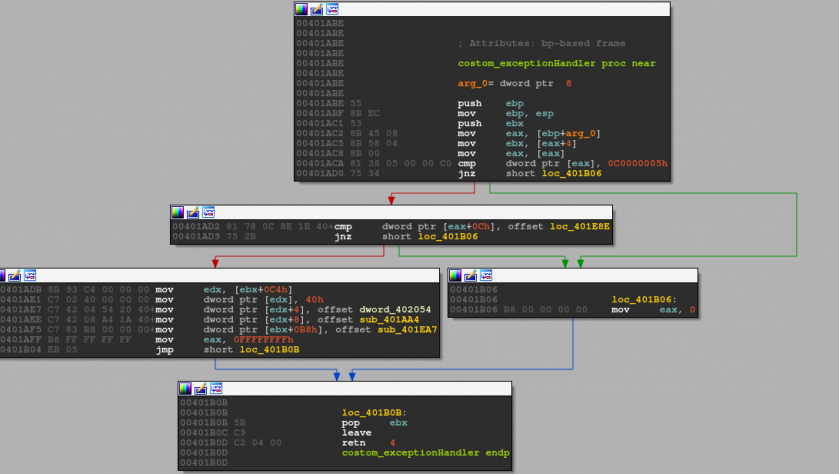

In this case, if the sample is not being debugged, control is passed immediately to the custom handler. The custom exception handler decrypts a piece of code that will be injected into another process later (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Custom exception handler.

Figure 11: Custom exception handler.

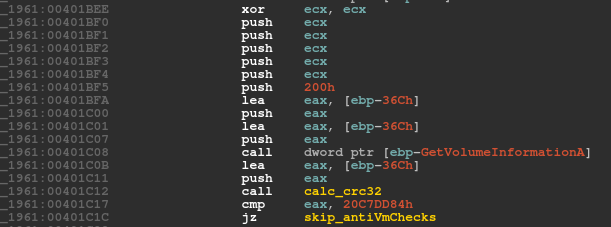

Versions 2.07 and 2.08 share another feature that controls whether the loader bypasses anti-VM and anti-debugging procedures. The loader calls GetVolumeInformationA on the 'C:\' drive and acquires the drive name. Next, it calculates the CRC32 of the drive name and compares it against a hard-coded value, 0x20C7DD84 (Figure 12). If they match, it bypasses the anti-forensics checks and proceeds directly to invoke the exception. The author probably used this technique to test the bot in his/her virtual machine without the need to go through the anti-VM/anti-analysis features.

Figure 12: Drive C checksum is calculated and compared to 0x20C7DD84.

Figure 12: Drive C checksum is calculated and compared to 0x20C7DD84.

Versions 2.09 and 2.10 evade debugging and analysis by implementing the same idea as previous versions, but this time in the payload. Eventually, in all versions, the loader injects the payload into a remote process using a process hollowing technique and runs it in memory.

As mentioned, the payloads of versions 2.09 and 2.10 start with some anti-VM tricks, despite the earlier versions having taken care of this in the loader. Like the older versions, they check for a list of blacklisted processes in case the machine is compromised. The number of blacklisted processes in version 2.09 is exactly the same as in 2.08, whereas it increases to 21 processes in version 2.10 (see Figure 13). Like versions 2.07 and 2.08, versions 2.09 and 2.10 calculate the CRC32 of the process name. However, instead of implementing the algorithm, they call RtlComputeCrc32 directly. If the bot finds any of the target processes, it runs a snippet of code to sleep for one minute in an infinite loop in order to evade detection.

Figure 13: The number of blacklisted processes increases in version 2.10.

Figure 13: The number of blacklisted processes increases in version 2.10.

If 'HKLM\software\policies' contains the registry key 'is_not_vm' and the key is VolumeSerialNumber, version 2.10 bypasses these checks. This behaviour is comparable to that in versions 2.07 and 2.08 where the bot checked the checksum of the root drive.

The main aim of Andromeda's payload is to steal the infected system's information, talk to the command-and-control (C&C) server, and download and install additional malware onto the system. In order to do this, it initiates a sophisticated command-and-control channel with the server. Each version of Andromeda uses a different format for the message and the report that it sends to the server.

As shown in Table 2, each version has two message formats, both sent as HTTP POST requests: Action Request and Task Report. Action Request contains the information exfiltrated from the compromised system; the bot sends it to the server after encryption. Task Report, as the name implies, provides a report about the accomplished task.

| Version | Action Request | Task Report |

| 2.06 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|bv:%lu|sv:%lu|pa:%lu|la:%lu|ar:%lu | id:%lu|tid:%lu|result:%lu |

| 2.07 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|bv:%lu|os:%lu|la:%lu|rg:%lu | id:%lu|tid:%lu|res:%lu |

| 2.08 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|bv:%lu|os:%lu|la:%lu|rg:%lu | id:%lu|tid:%lu|res:%lu |

| 2.09 | id:%lu|bid:%lu|os:%lu|la:%lu|rg:%lu | id:%lu|tid:%lu|err:%lu|w32:%lu |

| 2.10 | {“id”:%lu,“bid”:%lu,“os”:%lu,“la”:%lu,“rg”:%lu} {“id”:%lu,“bid”:%lu,“os”:%lu,“la”:%lu,“rg”:%lu,“bb”:%lu} |

{“id”:%lu,“tid”:%lu,“err”:%lu,“w32”:%lu} |

Table 2: Evolution of the message formats.

The Action Request format shares some essential tags among all versions, such as 'id' and 'bid', while some other tags are version‑specific, such as 'ar' in version 2.06 and 'bb' in version 2.10. It is only the last version of the bot that uses JSON format to communicate with the C&C server.

Table 3 describes the role of each tag in the format.

| Action Request | Task Report | ||

| Tag | Information | Tag | Information |

| id | Volume serial number of victim machine | id | Volume serial number of victim machine |

| bid | Bot ID, a hard-coded DWORD in payload | tid | Task ID provided by server |

| bv | Bot version | res/result/err | Flag indicating if task is successful |

| pa | Flag indicating whether OS is 32-bit or 64-bit | w32 | System error code, returned by RtlGetLastWin32Error |

| la | Local IP address acquired from sockaddr structure | ||

| ar/rg | Flag indicating if the process runs in the administrator group | ||

| sv/os | Version of the victim operating system | ||

| bb | Flag indicating if victim system uses a Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian or Kazakh keyboard | ||

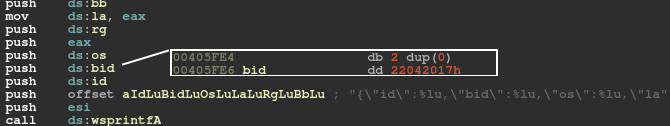

We believe that 'bid' is used to represent build ID and, interestingly, in some versions, like 2.06 and 2.10, it indicates a date in the format YYYYMMDD, as can be seen in Figure 14. In other instances, this tag represents a hard-coded random number. The latest observed 'bid' in version 2.10 is 22 May 2017, which suggests that development stopped then.

Figure 14: 'bid' value in version 2.10.

Figure 14: 'bid' value in version 2.10.

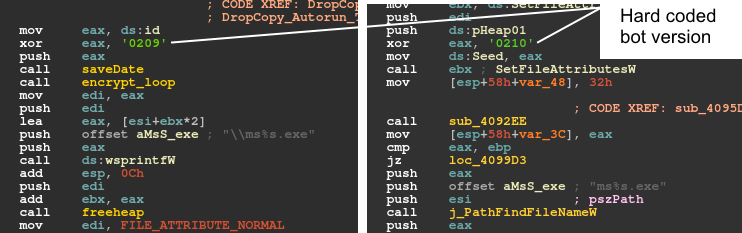

After version 2.08, 'bv', which indicates the bot version, is removed from the request message. However, in the two latest versions, there remains a clue as to the bot version, which is a hard-coded xor key. This xor key is used in five different places in version 2.09 and twice in version 2.10. In all cases, it xors the 'id' and will be further manipulated to be used as the file name or registry value (see Figures 15 and 16).

Figure 15: The bot version is represented as a hard-coded xor key and used as a file name.

Figure 15: The bot version is represented as a hard-coded xor key and used as a file name.

Figure 16: The bot version is represented as a hard-coded xor key and used in registries.

Figure 16: The bot version is represented as a hard-coded xor key and used in registries.

When the message is prepared for the required information, in all versions except the most recent one, the string is encrypted in two steps. The first step uses a 20-byte hard‑coded RC4 key and the second step uses base64 encoding. Version 2.10 encrypts the message only using the RC4 algorithm. After posting the message to the server, the bot receives a message from the server. The bot validates the message by calculating its CRC32 hash excluding the first DWORD, which serves as a checksum. If the hash equals this excluded DWORD, it proceeds to decrypt the message using the 'id' value as the RC4 key.

Next, it decodes the base64 string and obtains a plain text message. Received messages have the following structure:

struct RecvBlock {

uint8_t cmd_id;

uint32_t tid;

char cmd_param[];

};

According to the communicated cmd_id, the bot carries out a designated command which could be any number from the following: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9. In versions prior to 2.09, the bot is capable of performing all seven tasks. But in versions 2.09 and 2.10, it discards commands 4 and 5.

In Table 4 we take a look at each task and describe it further using static analysis of the code.

| cmd_id | Task type | Description |

| 1 | Download EXE | Using the domain provided in the command_parameter, the bot downloads an exe, saves it in the temp folder with a random name, and executes it. |

| 2 | Install plug-in | Using the domain provided in the command_parameter, the bot installs and loads plug-ins. |

| 3 | Update bot | Using the domain provided in the command_parameter, the bot gets the exe file to update itself. If a file named ‘Volume Serial Number’ exists in the registry, the bot drops the update in the temp folder and gives it a random name. Otherwise, the file is dropped in the current directory. This task is followed by cmd_id=9, which kills the older bot. |

| 4 | Install DLL | Using the domain provided in the command_parameter, the bot downloads a DLL into the %alluserprofile% folder with a random name and .dat extension. |

| 5 | Delete DLLs | The DLL loaded in cmd_id=4 is uninstalled. |

| 6 | Delete plug-ins | The plug-ins loaded in cmd_id=3 are uninstalled. |

| 9 | Kill bot | All threads are suspended and the bot is uninstalled. |

Table 4: The seven command IDs and their tasks.

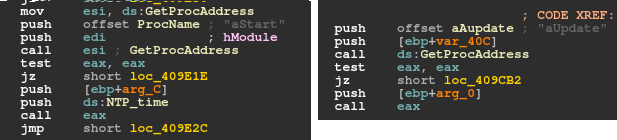

It is interesting to note that the cmd_id value changes a little in versions 2.09 and 2.10. As a result, the bot first downloads the plug-in and later finds three plug-in exports, aStart, aUpdate and aReport, using a call to the GetProcAddress API (Figure 17).

Figure 17: The payload also searches for plug-in exports aStart and aUpdate.

Figure 17: The payload also searches for plug-in exports aStart and aUpdate.

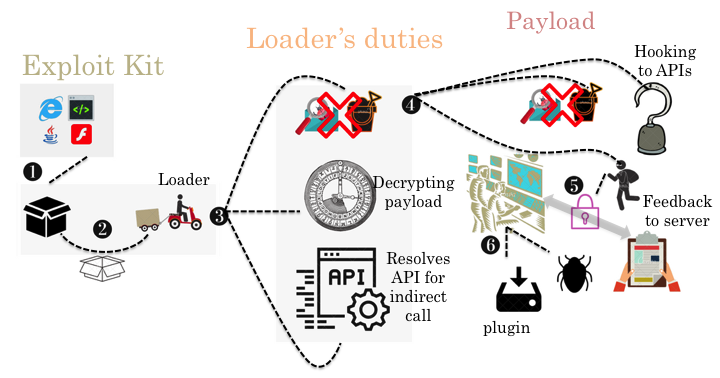

To summarize, Andromeda normally spreads via exploit kits located on compromised websites. The primary sample is packed and drops the loader after the unpacking stage. In the earlier versions of the bot the loader contains anti-VM and anti-analysis tricks. In all versions, the loader decrypts the payload and resolves APIs for indirect calls in the payload. As a result, using an anti-API hooking trick, the loader saves the first instruction of the API call into memory and jumps to the second instruction.

In the last two versions of the bot (2.09 and 2.10) the payload contains anti-VM and anti-analysis features. In version 2.07 and later versions, the payload leverages an inline hooking technique and hooks selected APIs. For example, in versions 2.07 and 2.08 the bot hooks GetAddrInfoW, ZwMapViewOfSection and ZwUnmapViewOfSection; in version 2.09 it hooks GetAddrInfoW and NtOpenSection; and in version 2.10 it hooks GetAddrInfoW and NtMapViewOfSection. In all versions, the bot steals information from the compromised system, sends the information to the server (after encryption), and waits for a command from the server.

Upon receiving a command from the server, the bot acts accordingly, installing plug-ins and downloading other malware. Finally, the bot sends a report about its mission to the server.

Figure 18: Andromeda at a glance.

Figure 18: Andromeda at a glance.

It has been a while since the last version of Andromeda was released. We have been waiting a long time for a new variant to emerge, but Reuters reported recently:

'National police in Belarus, working with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, said they had arrested a citizen of Belarus on suspicion of selling malicious software who they described as administrator of the Andromeda network.' [3]

Based on that, we can tentatively call this the end of the Andromeda era, and conclude that there won't be any further releases.

From 2011 to 2015, Andromeda kept analysts busy with its compelling features and functionality, and it remains among the most prevalent malware families today. Over the course of four years, five major versions were released, each new version being more complex than its predecessor. This guaranteed that Andromeda remained a sophisticated threat. A flexible C&C provided a wide range of functionality and efficiency, increasing the power of the threat by installing various modules. Meanwhile, it integrated several RC4 keys to encrypt data for C&C communications, thus making detection a significantly more complex challenge. Fortunately, however, analysts have become sufficiently familiar with Andromeda's ecosystem over the years to learn how to navigate all of its challenges.

[1] Tan, N. Andromeda 2.7 features. Fortinet blog. 23 April 2014. https://blog.fortinet.com/2014/04/23/andromeda-2-7-features.

[2] Xu, H. A good look at the Andromeda botnet. Virus Bulletin. May 2013. https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2013/05/good-look-andromeda-botnet.

[3] Sterling, T.; Auchard, E. Belarus arrests suspected ringleader of global cyber crime network. Reuters. 5 December 2017. https://ca.reuters.com/article/technologyNews/idCAKBN1DZ1VY-OCATC.

[4] Xu, H. Cracked Andromeda 2.06 spreads bitcoinn miner. Fortinet blog. 7 January 2015. https://blog.fortinet.com/2015/01/07/cracked-andromeda-2-06-spreads-bitcoin-miner.

MD5: 73564f834fd0f61c8b5d67b1dae19209

SHA256: 4ad4752a0dcaf3bb7dd3d03778a149ef1cf6a8237b21abcb525b9176c003ac3a

Fortinet detection name: W32/Kryptik.AFJS!tr

MD5: d7c00d17e7a36987a359d77db4568df0

SHA256: 44950952892d394e5cbe9dcc7a0db0135a21027a0bf937ed371bb6b8565ff678

Fortinet detection name: W32/Injector.ZVR!tr

MD5: b4d37eff59a820d9be2db1ac23fe056e

SHA256: 92d25f2feb6ca7b3e0d921ace8560160e1bfccb0beeb6b27f914a5930a33e316

Fortinet detection name: W32/Tepfer.ASYP!tr.pws

MD5: 3f2762d18c1abc67e21a7f9ad4fa67fd

SHA256: 2f44d884c9d358130050a6d4f89248a314b6c02d40b5c3206e86ddb834e928f6

Fortinet detection name: W32/BLDZ!tr

MD5: fb0a6857c15a1f596494a28c3cf7379d

SHA256: 73802eaa46b603575216fb212bcc18c895f4c03b47c9706cde85368c0334e0cd

Fortinet detection name: W32/Malicious_Behavior.VEX