2016-01-01

Abstract

A growing percentage of Android malware, including Zeus, SMSSend, and re-packaged applications, are packed using legitimate packers originally developed to protect the intellectual property of Android applications, with other malware having been found packed with customized packers. In his VB2014 paper, Rowland Yu attempts to address the anti-decompiler and anti-debugging techniques of such packers, reveals the latest statistics on Android packed malware, and presents a generic method for detecting packed Android malware.

Copyright © 2014 Virus Bulletin

Recently, SophosLabs has noticed an increase in the use of Android packers on APK files. Android packers are able to encrypt an original classes.dex file, use an ELF binary to decrypt the dex file to memory at runtime, and then execute via DexclassLoader. In other words, Android packers have the ability to change the overall structure and flow of an Android APK file – which is more complicated than obfuscation techniques such as the use of ProGuard, DexGuard and junk byte injection.

Android packers were originally created to prevent the intellectual property of applications being copied or altered by others for profit. ApkProtect.com and Bangcle.com are the first two legitimate providers of online packing services. Bangcle.com even employs virus-scanning engines in an attempt to prevent malicious applications being packed. However, the developers’ centralized measuring systems and scanning engines have not been able to prevent malware authors from using their services. A growing percentage of malware, including Zeus, SMSSend, and re-packaged applications, are packed by their services. SophosLabs has also found malware packed with a customized packer.

As a result, security researchers are facing a great challenge in overcoming these packers’ complex anti-decompiler and anti-debugging strategies. Existing reverse engineering (RE) tools are not able to unpack and inspect hidden payloads within packed applications. Android sandboxes have trouble offering dynamic analysis information, as packed applications on Android Emulator keep crashing. Therefore, distinguishing Android malware from a group of packed applications is much harder than it is from a number of obfuscated applications.

This paper attempts to address the anti-decompiler and anti debugging techniques of the above packers, reveal the latest statistics on Android packed malware, use static RE utilities to analyse their logic flow and data structures, and demonstrate runtime behaviours via dynamic tools. Furthermore, we are building solutions to investigate hidden payloads via restoration of the original Android dex files from memory dump. Finally, the paper will present a generic method to detect packed Android malware.

A packer is a program that is used to compress and/or encrypt an executable file without affecting its execution semantics [1]. Packers were originally created to reduce the overall file size for distribution, and/or to protect files’ intellectual property against reverse engineering (RE). Later on, malware authors took advantage of these benefits and began to utilize packers as a means to avoid detection by anti-virus (AV) scanners.

While on the one hand, Android packers have anti-tamper, anti decompiler, anti-runtime injection and anti-debug capabilities for the protection of legitimate applications against loss of intellectual property, on the other hand, they present enormous challenges for existing RE tools and dynamic analysis systems when diagnosing potential mobile threats.

A rise in the use of packers in Android malicious applications has recently been seen by SophosLabs. These include Zeus, SMSSend and re packaged adware, all of which are packed either by legitimate online packing services such as ApkProtect.com and Bangcle.com, or using customized packers. The key step in verifying a packed application – malicious or otherwise – is acquiring the original dex file.

This paper will:

Present an overview of the online Android packing services of ApkProtect.com, Bangcle.com and Ijiami.cn.

Address the anti-decompiler and anti-debug techniques of Android packers, and look at why Android packers are more complicated than obfuscation tools.

Report on Android malware families using various packers, and their challenges for existing threat researching tools and systems.

Describe the Volatility project and a plug-in for analysing packed malware and restoring the original dex file via memory dump.

Present a solution for detecting packed malware.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: in section 2, we provide a deep insight into the working process of Android packers and their techniques; section 3 discusses the challenges for existing RE tools and dynamic systems; section 4 presents the Volatility project, describes a new Volatility plug in, and demonstrates its results for a packed application. Finally, section 5 draws a conclusion.

There is a well-known saying: ‘Know the enemy and know yourself, and you can fight a hundred battles with no danger of defeat.’ It is necessary to understand the operating principles of Android packers in order to know what kinds of challenges confront us and how to build solutions. This section will illustrate our subjects – the top three Android packing service providers – ApkProtect.com, Bangcle.com and Ijiami.cn.

All Android packing services are based on online black box systems. Developers upload their applications then obtain packed applications without any knowledge of the internal workings of the packer. However, for a malware researcher, it is vitally important to understand the inner workings of the packed files so as to be able to analyse the payloads of malicious applications and offer suitable detection.

To make reverse engineering simpler, a test application was created and uploaded to all three online packing services. The application contained the main Android components: Activity, Service, Content Provider, BroadcastReceiver and Intent, together with JNI and native library. Subsequently, the packed applications were examined to determine the differences between them and the original file in terms of static and dynamic analysis in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the packing services.

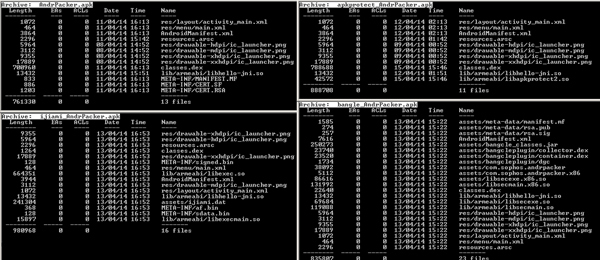

Figure 1 shows the differences in the file structure of the test application before and after packing by the three providers.

Figure 1. The APK file structure (top left: original APK, top right: file packed with ApkProtect, bottom left: file packed with Ijiami, bottom right: file packed with Bangcle).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 1.)

Table 1 lists the files added in the packed APKs, while Table 2 lists the files modified in the corresponding APKs.

| Pack provider | Added file | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| ApkProtect | lib/armeabi/libapkprotect2.so | ARM shared native library binary |

| Bangcle |

assets/meta-data/manifest.mf assets/meta-data/rsa.pub assets/meta-data/rsa.sig assets/bangcle_classes.jar assets/bangcleplugin/collector.dex assets/bangcleplugin/container.dex assets/bangcleplugin/dgc assets/com.sophos.andrpacker assets/com.sophos.andrpacker.x86 assets/libsecexe.x86.soassets/libsecmain.x86.so lib/armeabi/libsecexe.solib/armeabi/libsecmain.so |

APK manifest file Signature file The real signature file with certificate Encrypted original classes.dex file Bangcle information collector plug-in Bangcle implementation plug-in Bangcle plug-in log file ARM exectuable file x86 executable file x86 shared native library binary x86 native main binary ARM shared native library binary ARM native main binary |

| Ijiami |

META-INF/signed.bin META-INF/af.bin META-INF/sdata.bin assets/ijiami.dat lib/armeabi/libexecmain.so lib/armeabi/libexec.so |

Ijiami signed binary file Ijiami binary file Ijiami RSA signature file Encrypted original APK file ARM JNI load/unload native binary ARM shared native library binary |

Table 1. The files added in the packed APKs.

| Pack provider | Modified/replaced file | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| ApkProtect | classes.dex | Modified original classes.dex file |

| Bangcle |

AndroidManifest.xml classes.dex |

Configure to implement Bangcle class

Classes.dex replaced by Bangcle |

| Ijiami | AndroidManifest.xml

classes.dex |

Configure to implement Ijiami class

Classes.dex replaced by Ijiami |

Table 2. The files modified/replaced in the packed APKs.

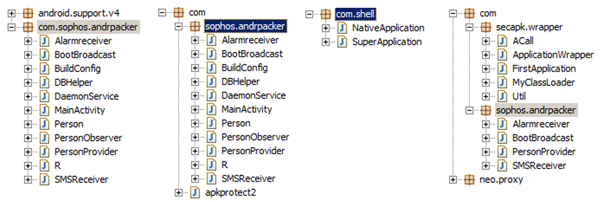

Figure 2 displays the code tree of the decompiled classes.dex file for the original APK, and for the file packed with ApkProtect, Ijiami and Bangcle (from left to right, respectively).

Figure 2. Code tree of decompiled classes.dex. From left to right: original, ApkProtect, Ijiami and Bangcle.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 2.)

After investigating the code tree of the decompiled classes.dex, we can conclude that ApkProtect is not an Android packing service, but an obfuscating and junk code injecting tool. It is able to encrypt most sensitive strings by using the AES cipher algorithm in the apkprotect2 class, but will not touch the original logic flow and code structures. Therefore, it is relatively simple to analyse and detect applications guarded by ApkProtect.

On the other hand, both Bangcle and Ijiami provide complete packing services. Bangcle supplies a group of standard classes, but still shows encapsulated BroadcastReceiver and Content Provider components from the original classes.dex. Ijiami goes a step further, by replacing the original dex file with its own standard NativeApplication and SuperApplication classes.

Sections 2.1 and 2.2 covered the APK file structure and the code tree of the packed application. However, several key technical issues need to be addressed in order to understand the unpacking process of Ijiami:

Technical issue (1): How to make sure the unpacked code is executed initially.

The key to this technical issue is the Android Application class. The Android reference page [2] describes the Application class as the ‘Base class for those who need to maintain global application state. You can provide your own implementation by specifying its name in your AndroidManifest.xml’s <application> tag, which will cause that class to be instantiated for you when the process for your application/package is created.’ As the context of the entire application, the Application class will be the starting point when executing the program.

When expanding the code tree and taking a detailed view of two standard classes in Ijiami, we found that the SuperApplication class extends Application class accounts to load and run the NativeApplication class, while the NativeApplication class is responsible for loading the native library binary for unpacking (shown in Listing 1).

package com.shell;

import android.app.Application;

public class NativeApplication

{

static

{

System.loadLibrary(“exec”);

System.loadLibrary(“execmain”);

}

public static native boolean load(Application paramApplication, String paramString);

public static native boolean run(Application paramApplication, String paramString);

public static native boolean runAll(Application paramApplication, String paramString);

}

package com.shell;

import android.app.Application;

import android.content.Context;

public class SuperApplication

extends Application

{

protected void attachBaseContext(Context paramContext)

{

super.attachBaseContext(paramContext);

NativeApplication.load(this, “com.sophos.andrpacker”);

}

public void onCreate()

{

NativeApplication.run(this, “android.app.Application”);

super.onCreate();

}

}

Listing 1: NativeApplication and SuperApplication classes of Ijiami.

Technical issue (2): Where and how to unpack the original dex file, then how to dynamically load the unpacked code.

Lib/armeabi/libexec.so supplies comprehensive code to implement the above functionalities. First, it recognizes and interprets files in the META-INF directory to verify the signature and integrity of encrypted data by using the RSA and AES crypto algorithms, then it decrypts assets/ijiami.dat to the original classes.dex in memory. The library binary then uses the DexClassLoader class to realize the dynamic loading of the unpacked code.

Technical issue (3): Stop runtime anti-debug by modifying the dex header.

When analysing the Ijiami packing service, we discovered that it has the ability to change the original dex header. The modification starts at the beginning of the dex file and runs to 0x28 bytes, filling it with random values. As a result, it can stop runtime debugging to trace the original dex file in memory by searching for DEX_FILE_MAGIC ‘dex\n035\0’. However, this also causes problems for the Volatility project (described in section 4) in locating the original dex file in memory.

This subsection explains the anti-tamper, anti-decompiler, anti runtime injection and anti-debug capabilities of Bangcle, based on detailed reverse engineering analysis. Let us begin with the entrypoint of the source code – the ApplicationWrapper class, as shown in Listing 2.

public void onCreate()

{

super.onCreate();

if (Util.getCustomClassLoader() == null) {

Util.runAll(this);

}

String str = FirstApplication;

try

{

this.cl = ((DexClassLoader)Util.getCustomClassLoader());

realApplication = (Application)getClassLoader().loadClass(str).newInstance();

if (realApplication != null)

{

localACall = ACall.getACall();

localACall.at1(realApplication, getBaseContext());

localACall.set2(this, realApplication, this.cl, getBaseContext());

}

}...

Listing 2: Entrypoint of Bangcle source code – ApplicationWrapper class.

The Util class in the entrypoint of the source code implements the main functionalities in the Applications layer of the Android architecture. The functionalities include verifying the integrity of classes.dex, checking if the architecture is x86 or ARM, copying the required native library binaries, encrypted classes.jar, and JNI binary to specific locations, creating child processes, then using the MyClassLoader class to load the decrypted classes.jar at runtime. Listing 3 displays the core method in the Util class.

public static void runAll(Context paramContext)

{

x86Ctx = paramContext;

doCheck(paramContext); // checking integrity of classes.dex

checkUpdate(paramContext);

try

{

File localFile = new File(“/data/data/” + paramContext.getPackageName() + “/.cache/”);

if (!localFile.exists()) {

localFile.mkdir();

}

checkX86(paramContext); // If it is x86 platform, copy related library binary

CopyBinaryFile(paramContext); // copy encrypted classes.jar and JNI binary

createChildProcess(paramContext); // create child processes

tryDo(paramContext);

runPkg(paramContext, paramContext.getPackageName()); // call MyClassLoader

return;

}...

Listing 3: Runall method of Bangcle’s Util class.

Meanwhile, Bangcle’s ACall class deals with binaries such as libsecexe.so in the Android Libraries layer. However, it is impossible to establish a relationship between the Java source code and the libsecexe.so binary since almost all function names in the binary are encrypted (shown in Figure 3). The standard format of the method name should follow the following template: Java_package_class_method, namely the Java package name, class name, then function method name [3].

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 3.)

When it is running, the Bangcle-packed application creates three processes (shown in Figure 4) instead of only one process in the original application. Moreover, the three processes in Bangcle are performing ptrace (process trace) so that debugging tools like gdb have trouble connecting them. This is because ptrace in Android limits only one process to observe and examine the trace’s memory and registers. Figure 4 also demonstrates the evidence of mutual tracing in three Bangcle processes [4], [5].

Finally, we summarize Bangcle’s capabilities:

Anti-temper – the Util class provides hash checking to check the integrity of classes.dex.

Anti-decompiler – the Util class also decrypts classes.jar in memory and employs MyClassLoader to load the decrypted .jar file at runtime.

Anti-runtime injection – it is impossible to establish a relationship between the ACall class and libse-cexe.so due to the encryption.

Anti-debug – Bangcle employs an anti-ptrace technique to prevent analysis by debugging tools.

Section 2 demonstrated the packing and unpacking processes of ApkProtect, Bangcle and Ijiami on the basis of comparing the file structures, analysing decompiled resource code, and runtime debugging. This section will introduce and describe the challenges for security researchers posed by the above packing services.

Figure 5 shows a trend line of Android malicious applications based on three packers. Since September 2013, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of malicious applications packed using Bangcle – Bangcle’s scanning engines have not been able to achieve the developers’ aim of avoiding packing malware applications. Meanwhile, the use of ApkProtect and Ijiami has seen a continuous and steady growth over the last five months.

Existing RE tools are not able to disassemble the payloads of packed samples due to the anti-decompiler characteristics of packers. The payloads of packed samples are encrypted by advanced cryptographies such as AES and DES. The packing process and the crypto key generation are classified as confidential. Moreover, the algorithms are embedded in the native binaries to make RE much more difficult.

Dynamic analysis systems such as DroidBox, Apk-Analyzer.net and Ijinshan.com [6] are unable to offer successful dynamic results for packed Android applications. The systems either provide very basic static information or simply crash when attempting to start applications. Figure 6 shows screenshots of the running behaviours of the test application in DroidBox and Ijinshan.com.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 6.)

So far, Android packers present two runtime anti-debug challenges: Ijiami is capable of modifying the dex header to prevent memory searching, while Bangcle prevents anti debugging by creating three interactive processes. Both cause serious consequences for existing debugging tools – even the Volatility project (see section 4).

By taking advantage of Android packers, cybercriminals are able to change an application’s dex file as a means of thwarting signature-based scanners. Even if an anti virus scanner has a database that includes the signature of the original APK sample, it will be unable to detect the newly packed version of the malware. Figure 7 displays a recent SMSSend example, showing the original malware as well as the version packed with ApkProtect.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 7.)

This part is split into three sections: section 4.1 will outline the required environment and steps for memory acquisition. Section 4.2 will concentrate on the Volatility framework and describe a new plug-in for analysing acquired memory and locating the offset of the unpacked dex file in the memory map. Finally, section 4.3, will demonstrate the usage of the Volatility plug-in to locate the offset of the unpacked dex file, write selected memory mapping to disk and patch back the dex header if required.

In order to perform memory analysis, a copy of the RAM from a target Android device or emulator is required. As Android is based on Linux, a newly developed Loadable Kernel Module (LKM), named LiME (Linux Memory Extractor) [7] is used for acquisition of volatile memory. It is necessary to cross compile LiME for use on an Android device/emulator. Additional steps are required for the prerequisites and environment setting. These steps, which can be found in several online wiki documents ([8], [9], [10], [11]) consist of:

Initialize an Android build environment including path and required package on either a Linux or OSX system.

Download the Android SDK and NDK.

Download the Android kernel source code.

Cross compile the kernel.

Create AVD then emulate the custom kernel with the AVD.

Download and cross compile LiME.

Load LiME on the Android device/emulator.

Acquire memory.

Volatility [12] is a single and cohesive framework for memory analysis of Windows, Linux, Mac and Android systems. It is open source, Python based, extensible and has scriptable APIs. Volatility also pre-ships with a list of very useful plug-ins for Android including Linux_pslist (which gathers active tasks by walking the task_struct), Linux_proc_maps (which gathers process maps for Linux), and Linux_dump_map (which writes selected process memory mappings to disk). However, a working Android Volatility profile with specific module.dwarf and the System.map is required to use these plug-ins. The configuration can be found in [12].

The following is the core part of this paper: a Volatility plug-in is designed to locate the offset of the original dex file in the memory map via a specific process ID (PID). The relevant code of the plug-in is shown in Listing 4.

1 signatures = {

2 ’map_header’ : ’rule map_header { \

3 strings: \

4 $hex = {00 00 ?? ?? 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 70 00 00 00 02 00} \

5 condition: $hex }’

6 }

7

8 class apk_packer_find_dex(linux_common.AbstractLinuxCommand):

9 ”””Gather information about the dex Dump in Memory running in the system”””

10

11 def __init__(self, config, *args, **kwargs):

12 linux_common.AbstractLinuxCommand.__init__(self, config, *args, **kwargs)

13 self._config.add_option(’PID’, short_option=’p’, default=None,

14 help=’Operate on a specific Android application Process ID’,

15 action=’store’, type=’str’)

16

17 def calculate(self):

18 ””” Required: Runs YARA search to find hits ”””

19 rules = yara.compile(sources = signatures)

20

21 proc_maps = linux_proc_maps.linux_proc_maps(self._config).calculate()

22

23 for task, vma in proc_maps:

24 if not vma.vm_file:

25 if vma.vm_start <= task.mm.start_brk and vma.vm_end >= task.mm.brk:

26 continue

27 elif vma.vm_start <= task.mm.start_stack and vma.vm_end >= task.mm.start_stack:

28 continue

29 elif vma.vm_end - vma.vm_start > 0x1000:

30 proc_as = task.get_process_address_space()

31 maxlen = vma.vm_end - vma.vm_start

32

33 data = proc_as.zread(vma.vm_start, maxlen - 1)

34

35 if data:

36 for match in rules.match(data = data):

37 for moffset, _name, _value in match.strings:

38 (usize,) = struct.unpack(‘I’, data[moffset - 4 : moffset])

39

40 i = 0

41 offset = moffset

42 while i < usize:

43

44 (maptype,) = struct.unpack(’H’, data[offset: offset+2])

45 (mapoffset,) = struct.unpack(’I’, data[offset+8: offset+12])

46

47 if maptype == 0x1000:

48 yield task, vma, moffset - 4 - mapoffset, moffset

49 break

50 i += 1

51 offset += 12

52

53 def render_text(self, outfd, data):

54 self.table_header(outfd, [(”Task”, ”10”),

55 (”VM Start”, ”[addrpad]”),

56 (”VM End”, ”[addrpad]”),

57 (”Dex Offset”, ”[addr]”),

58 (”Map Offset”, ”[addr]”)])

59 for (task, vma, offset, moffset) in data:

60 self.table_row(outfd, task.pid, vma.vm_start, vma.vm_end, offset, moffset - 4)

Listing 4: Apk_packer_find_dex plug-in.

In Volatility, each plug-in is able to call another one. Additionally, the results from one plug-in can be provided for further processing in other plug-ins [13]. A plug-in usually consists of a class name and three standard functions [14]: __init__(), calculate() and render_text(). In Listing 4, the class name is apk_packer_find_dex. The first function of the __init__() plug-in is the constructor of the class object with the capability of calling the super class constructor and/or defining additional command line options. The apk_packer_find_dex plug-in specifies a parameter name (--PID), a short option (-p) and help description.

The calculate() function loads an address space, accesses and parses the data, then prepares the output. Line 21 in the calculate() function in Listing 4 gets a process mapping list from a specific PID (the same as /proc/$PID/maps). The list contains the mapped memory regions and the access permissions of the heap, stack, and dynamically linked libraries. Lines 23–33 are a loop to read data from anonymous mappings because the original dex file should be unpacked in one of them. Lines 36-37 utilize a YARA rule to locate the offset of the map_list in the dex file. The YARA rule is declared in variable signatures based on the map_list structure shown in Figure 8.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 8.)

As discussed in section 2.3, the dex header is modified by the Ijiami packer, the map_list structure is thus a credible alternative for finding the original dex file. We know that the map_items in a map_list should start from TYPE_HEADER_ITEM, then TYPE_STRING_ID_ITEM followed by TYPE_TYPE_ID_ITEM. We also know that the size (count of the number of items) of HEADER_ITEM must be one, while HEADER_ITEM_OFFSET should begin from 0x0000, and header_size is always 0x70. All of these findings help to assign a specific search string for $hex in the YARA rule.

Once the offset of the map_list has been discovered, lines 41–47 in the calculate() function keep scanning map_list to find TYPE_MAP_LIST and the corresponding map_list_offset. Line 48 uses yield to generate a list of outputs including virtual memory start and end offsets as well as the dex and map_list offset in the memory. Finally, the render_text() function accepts the outputs and prints the data on screen in a standard fashion.

We use quotation marks around the word ‘original’ because we can’t acquire the raw dex file: Bangcle inserts its monitoring code into the original dex file before packing, and it is difficult to restore the first 0x28 bytes in the header section for an Ijiami dex file. However, the closest to the original dex file can be acquired using the following four steps:

Get the process ID of the target application by using Linux_pslist.

Locate the header and map_list offset of the unpacked dex file by looking at the apk_packer_find_dex plug-in output (shown in Listing 5).

$ python vol.py --profile=LinuxGolfish-2_6_29ARM -f lime.dump apk_packer_find_dex -p 876

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.3.1

Task VM Start VM End dex Offset Map Offset

---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

876 0x4c10d000 0x4c1a4000 0x28 0x8ffc8

Listing 5: Example output of the apk_packer_find_dex plug-in.

Dump a memory range specified by the Linux_dump_map plug-in to disk.

Patch DEX_FILE_MAGIC back if required, for instance, into an unpacked dex file from Ijiami packer.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 9.)

This paper provides an overview of the most popular Android packers: Bangcle, ApkProtect and Ijiami. It demonstrates the working principles of each in terms of static and dynamic analysis. Moreover, the paper describes some particular characteristics including dex header modification by Ijiami as well as the anti-ptrace technique employed by Bangcle.

A series of challenges have been discussed in section 3. These challenges include the explosive increase of Android malicious applications packed by three different packers, the inefficiency of existing reversing engineering tools, the failure of dynamic analysing systems, the anti-debug features, and the obstruction of generic detection.

Section 4 delivered an outline of the Volatility project. The Volatility project provides an open and complete framework for memory extraction and investigation. Volatility supports memory dump from Windows, OSX, Linux and Android, and supplies plenty of plug-ins for memory analysis. However, a customized plug-in named apk_packer_find_dex has been created to explore the process map list and locate the offset of the unpacked dex file in memory. We also demonstrated the acquisition of the original dex file with DEX_FILE_MAGIC patching.

In conclusion, the paper provides a practical solution for acquiring the original dex payload for a packed Android application. However, developing an efficient and effective detection solution for packed malware is a complicated task as it is impossible to unpack a piece of packed malware and detect the payload in the real world. On account of the background and information given in section 2, a detection solution can be based on a combination of AndroidManifest.xml, the size of the encrypted payload, resource files, and resources.arsc.

[1] Guo, F.; Ferrie, P. Chiueh, T.-C. A Study of the Packer Problem and Its Solutions. Symantec Research Laboratories, Pages 98 – 115, ISBN: 978-3-540-87402-7.

[3] Android on x86: Java Native Interface and the Android Native Development Kit. http://www.drdobbs.com/architecture-and-design/android-on-x86-java-native-interface-and/240166271.

[7] LiME – Linux Memory Extractor. https://code.google.com/p/lime-forensics/.

[9] Getting Started: Building Android From Source. http://xda-university.com/as-a-developer/getting-started-building-android-from-source.

[12] Volatility – An advanced memory forensics framework. https://code.google.com/p/volatility/.

[13] Macht, H. Live Memory Forensics on Android with Volatility. https://www1.informatik.uni-erlangen.de/filepool/publications/Live_Memory_Forensics_on_Android_with_Volatility.pdf.