2014-10-17

Abstract

In his VB2014 conference paper, Jean-Ian Boutin looks at the current webinject scene and how it has evolved over time, going from simple phishing-like functionalities to automatic transfer system (ATS) and two-factor authentication bypass, along with mobile components and fully fledged web control panels to manage money exfiltration through fraudulent money transfers.

Copyright © 2014 Virus Bulletin

Webinject files are now ubiquitous in the banking trojan world as a means to aid financial fraud. What started as private and malware-family-dependent code has blossomed into a full ecosystem where independent coders are selling their services to botnet herders. This specialization phenomenon can be observed in underground forums, where we see a growing number of offers of comprehensive webinject packages providing all the functionalities required to bypass the latest security measures implemented by financial institutions.

Our research covers the current webinject scene and its commoditization. We will take a look back and show how it has evolved over time, having started with simple phishing-like functionalities and now offering automatic transfer systems (ATS) and two-factor authentication bypass, along with mobile components and fully fledged web control panels to manage money exfiltration through fraudulent transfers.

Nowadays, a piece of malware that can inject arbitrary HTML content into a browser is all that a resourceful botmaster needs, as he can outsource virtually every other step in the process of performing a successful fraudulent financial transfer.

This has been confirmed by our recent observation of several malware families using the same webinject kits. Our research attempts to answer the question: will we see a consolidation phase, leading to the emergence of a few omnipresent webinject kits, similar to what we have seen in the web exploit kit scene?

Webinjects are one of the most advanced tools used by banking trojans to help defraud people’s bank accounts. As banking security measures have become more complex, there has been an increase in offerings for these products in underground markets. Webinjects have been around for several years already, but many of their features are still evolving.

This paper describes the evolution of the techniques used by webinject coders, as well as how the offerings of such criminal tools have evolved over the years. As the webinject configuration files become more and more advanced, it is becoming easier for researchers to identify the source of each webinject. As will be seen later on, it is now possible to track the webinject kits used in several distinct banking trojans, making it possible to see which offering is the most popular amongst the botmasters.

As users are relying increasingly on Internet banking to carry out their banking operations, cybercriminals are developing new ways to attack and compromise the very tools that are used in Internet banking: computers and mobiles. In the beginning, banking trojans targeted a handful of financial institutions and mainly used keyloggers and form-grabbing modules in an attempt to steal the users’ Internet banking credentials. While a keylogger is able to grab the user login and password as the user types them, it also creates huge amounts of useless data. All of the recorded data then needs to be parsed and searched by the botmaster in order to sort the useful information from the useless. Form grabbing was a clear evolution of this technique, as it grabs data that is entered into a web form, enabling the banking trojan to collect a user’s credentials as he is sending them to the server.

Form grabbing in this context is a rudimentary method of grabbing all GET/POST requests as they are sent to an external server. Well known banking trojans like Zeus [1] and SpyEye [2] first implemented [3] form grabbing by hooking web browser APIs. Some malware also implements form grabbing through the monitoring of network flows (pcap) [4]. API hooking is the preferred method, as it can intercept data before it is encrypted and sent to the server by the client’s browser. The functions hooked are browser-specific, and browser updates can disrupt the malware’s ability to intercept the data.

Nowadays, while some malware families still use this technique, most of the more advanced banking trojans are using webinjects to give them finer control over what is stolen from the user’s browser session. Moreover, webinjects can be used to modify the content of the web page the user is seeing, enabling a whole new range of nefarious activities on the compromised computer. Most webinjects include JavaScript, which allows cybercriminals to add code to the page to perform any type of action. As we will see later on, there are now several types of webinject ‘kits’ available for sale on underground forums, many of them using off-the-shelf JavaScript libraries such as jQuery.

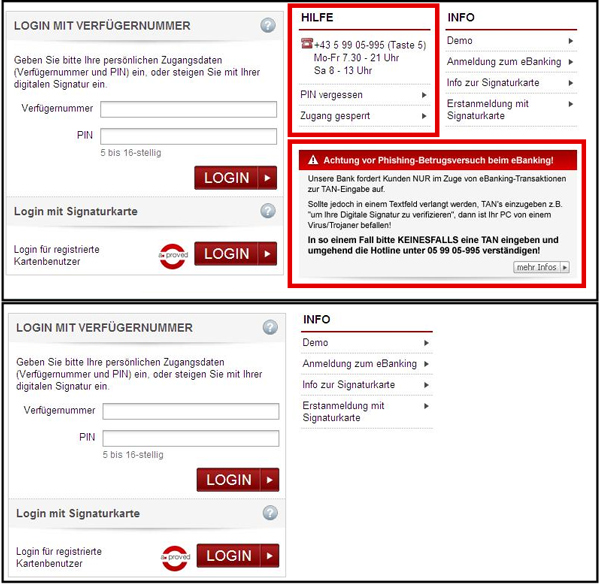

Popularized by well-known banking trojans like Zeus and SpyEye, webinjects are used by cybercriminals to target specific websites and alter their content. The web page content manipulation is possible through browser API hooking, just like the form-grabbing capability discussed before. The banking trojan can inspect the content received from the server and modify it on the fly before displaying it in the browser. This is a very powerful technique that can be used to deceive the user, as he will believe that the content he is seeing has been received directly through his bank’s website. This technique is widely known as a man-in-the-browser (MITB) attack. Figure 1 shows a webinject in action, where the fraudsters have simply removed a warning from the original login page.

Figure 1. Content removal using a webinject. Top: login page as seen on a clean system. Bottom: login page as seen on a compromised system (warnings removed).

The target and content to be added to a given web page is contained within a file called a webinject configuration file, which is typically downloaded by the infected computer from the command and control (C&C) server. This is another great advantage for the cybercriminals: the target, as well as the content to be injected into the web page, can easily be changed as long as the bot can download a new configuration file from the C&C. There exist several webinject configuration file formats, but the one popularized by older banking trojans such as SpyEye is now the de facto standard. Figure 2 shows an example of such a webinject configuration file.

As can be seen above, the target URL is specified first. There are then some letters next to the URL, which tell the banking trojan what action to perform when this URL is browsed to. Table 1 lists the meaning of each letter that can be found after the target URL, and Table 2 shows the different tags that are contained in the webinject configuration file.

| set_url common flags | Meaning |

|---|---|

| G | All GET requests should be inspected for possible injection. |

| P | All POST requests should be inspected for possible injection. |

| L | Used for logging purposes. Capture all content specified within data_before, data_inject and data_after. |

| H | Used for logging purposes. Capture the content that was left over by the ‘L’ flag. |

Table 1. set_url common flags.

| Common tags | Meaning |

|---|---|

| set_url | Specify target URL for webinjects. Regular expressions are supported and widely used. |

| data_before/data_end | Specify that the injected content should be placed just after this content. |

| data_inject/data_end | The content to be injected into the target web page. |

| data_after/data_end | Specify that the injected content should be placed just before this content. |

Table 2. Webinject configuration file common tags.

Some of the webinjects are very basic and have phishing-like features where, for example, boxes are added to a target website, asking the user for additional personal information. This additional information can later be used by the fraudster for various purposes such as accessing the user’s bank account, stealing his credit card number or selling his personal information (see Figure 3).

As time goes on, webinjects are becoming more and more specialized. In fact, some of them have advanced features that can automate transfers from the user’s bank account [5]. These scripts are customized as per the banking website and will try to circumvent any security measure put in place by the bank. As the banks are trying to add checks in their backend to detect these kinds of automatic tricks, the cybercriminals are coming up with different techniques to hinder detection. In Figure 4, you can see a webinject where the attackers insert random timeouts between steps to mimic human behaviour.

Once the fraudulent transfer from the compromised account to an attacker-controlled account has been made, these webinjects often have mechanisms to hide the transaction and amend the current account balance so that the user will not be aware of the transfer if he accesses his bank account through the compromised computer.

These ATS attacks were very popular in the past [6], but their popularity has diminished as the success-rate-to-complexity ratio has decreased. We still see some ATS attacks in the wild, but several cybercriminals now prefer using ‘manual’ attacks, where they simply take control of a host or route their traffic through it and perform the fraudulent actions manually.

As online fraud grew, banks increased their security measures. One of the most popular security techniques is to add multi factor authentication to important transactions such as login or performing a transfer. Some are more rudimentary and use a simple printed list of Transaction Authorization Numbers (TANs or iTANs), while others are far more sophisticated and involve the user’s mobile (mTANs) or an electronic device used in combination with the user’s bank card (chip-TANs). If multi factor authentication is implemented, the bank will ask for a specific TAN when the user makes a sensitive transaction on the bank’s website. The user then has to provide it either by looking on the list that was given to him (TAN), by checking an SMS that was just sent to his phone (mTAN), or by inserting his bank card into his chip TAN.

To circumvent mTANs, the cybercriminal can coerce the user into installing a piece of malware on his phone that is able to intercept SMS messages. This is usually done through social engineering. Once the user logs into his bank account, he will be shown a screen similar to the one shown in Figure 5, asking for his phone number, brand and OS.

(Click here for a larger version of Figure 5.)

Once this has been done, the user will receive an SMS on his phone with a link to a malicious application. He can also scan a QR code or browse directly to a link on his mobile in order for the malware to be downloaded on his phone. The user will then have to install the application manually. As the overall procedure involves several steps, fraudsters frequently inject a ‘manual’ into the web page the user is seeing, guiding him step by-step through the installation process. Once the malware has been installed on the phone, it will be able to redirect any SMS messages received on the user’s phone to the attacker, providing a means for the attacker to bypass mTANs. Perkele and iBanking are two well-known mobile malware families that have this capability.

As many banks incorporate some form of multi-factor authentication before allowing transfers to be conducted, webinjects must try to circumvent them. They have social engineering mechanisms built in to lure the user into providing enough information to enable the transfer to go through. Our monitoring of different botnets has enabled us to see a myriad of different schemes that are used to fool the user into providing a transaction authorization number. Whether it is an index-TAN (iTAN), mobile TAN (mTAN or mToken) or chip-TAN that is used, the schemes are somewhat similar. The user will be shown a pop-up window telling a false story as he is logging into his bank account. One such lie involves telling the customer that a transfer has been made in error, and that he must correct it by sending the money back. This particular scheme is made possible by a balance changer inside the webinject that will show the user an inflated balance, supporting the idea that the transfer really happened. Another scheme we have seen is to tell the user that his device must be calibrated through a test transfer. These are only a couple of the examples we have witnessed, but they show the extent of the fraudsters’ creativity.

Figure 6 shows a screenshot asking a user for a TAN from his iTAN list. These lists of TANs are handed out by banks on a sheet of paper, each one having a particular index. When an authorization is necessary, the bank will ask for a specific TAN using its index on the list. In this example, the fraudsters are attempting a fraudulent transfer and have been asked for a particular TAN by the bank. To obtain this TAN, they have injected the image shown in Figure 6 into the web page and are trying to trick the user into providing the TAN, purportedly for a special digital signature.

Although most of the webinjects target financial institutions, there are some that target popular Internet services such as Facebook, Twitter, Google and Yahoo. These webinjects will generally ask for personal information, such as credit card information, once the user logs into one of these services from a compromised computer. No web service is immune from this type of attack. Figure 7 shows a webinject targeting Twitter asking the user for his credit card number.

As the webinject configuration file contains key information for security researchers and CERT organizations worldwide, its creators attempt to make its content as hard to obtain as possible. Initially, banking trojans downloaded webinject configuration files in unencrypted form or using weak encryption mechanisms. As a growing number of analysts began tracking these configuration files, cybercriminals started to make the process of decrypting them harder and harder. Banking trojans such as Zeus and its variants now use several layers of encryption and store the configuration files in parts, meaning that the full webinject configuration file is never fully decrypted in memory.

Although several tools exist to obfuscate JavaScript code, and several cybercriminals are using them heavily (exploit kit authors for example), it is surprising to see that most of the webinject configuration files are not obfuscated, or only use compressors that are easily reversible. This might be due to the fact that they are usually delivered to the client in encrypted form, but it is surprising nonetheless.

This well-known technique [7] for compressing JavaScript is found in many webinject configuration files and is very easy to reverse. The reversing can be done using a simple replacement of the ‘eval’ function, and then JS beautifier [8] can make the script analysis easier. This compressor is handy to reduce the script size and accelerate the web page download, but does little in terms of making the code harder to analyse. Figure 8 shows an example of a script that has been compressed using /packer/.

Some types of obfuscation can slow down the webinject analysis considerably, as deobfuscation of these kinds of scripts is not trivial. The example in Figure 9 shows a webinject using variable assignment and conditional statement obfuscation: what should be very simple variable assignments and conditional statements are replaced with several mathematical operations that complicate the analysis.

Although not insurmountable, this type of obfuscation certainly hinders analysis. Although obfuscation like that depicted above is currently infrequent, we will most likely see more of it in the future. As the complexity of webinjects increases, so does the likelihood that their authors will try to protect their intellectual property more efficiently.

The multiplication of banking trojan platforms and the increase in complexity and security around bank websites have led to an increase in the demand for quality webinjects. This demand is now matched by several offerings in underground forums.

Just like many other goods [9], webinject configuration files are openly sold by several different actors, many of whom have ties with traditional organized crime groups [10]. With this phenomenon comes a standardization of the webinject configuration file format. As most webinject coders are now relying on this format to write their webinjects, most of the newer banking trojans are also using the format depicted in Figure 2. In fact, some banking trojans are also bundling converters in order to be compatible with as many webinject formats as possible. This was the case with banking trojan Gataka which bundled a tool to convert SpyEye webinject configuration files to its own format.

As the demand for webinjects rises, the offerings also naturally increase. People writing these webinjects need tools to ease the process of writing and testing webinjects. Config Builder, which was part of the Carberp source code leaked in 2013, is an example of such a tool. It bundles an editor and a version of Internet Explorer for webinject development and testing.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of webinjects for sale: those that have advanced capabilities such as automatic transfer or an account balance grabber, and those that are simpler and feature only a phishing-like pop-up that asks the user for personal data as he is logging in. In fact, some webinject coders sell features à la carte [11], depending on the customer’s needs. It is not uncommon to see the work of several different webinject coders used as part of the same campaign within a particular banking trojan. Some operators have compromised hosts in several countries and are therefore trying to target as many financial institutions as possible. Others target specific regions of the world and thus require webinjects targeting institutions in these regions.

We have encountered several different offerings in underground forums, some of which are very cheap, while others are much more expensive. Some sellers, such as the one shown in Figure 10, are selling cheap webinjects that target a wide array of financial institutions.

(Click here for a larger version of Figure 10.)

This actor is selling webinjects targeting financial institutions in several countries. The webinjects can be bought for around one hundred dollars each. They all have the same functionalities: they are designed to steal personal information from the user by injecting fake forms into legitimate bank websites.

Of course, there are much more comprehensive offerings which implement ATS, multi-factor authentication bypass, and even the bundling of a mobile component to compromise the user’s mobile in order to intercept mTANs.

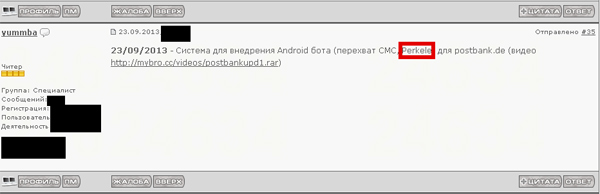

In the advert shown in Figure 11, the seller is saying that Perkele [12] is bundled with the webinject. This mobile malware is used to bypass mTANs as a multi-factor authentication measure. Most of the advanced webinjects now come with an administration panel that can be used to track the state of the compromised host, and control them.

Figure 11. Webinject coder bundling Perkele, a mobile component able to intercept SMS messages, as part of a webinject offering.

(Click here for a larger version of Figure 11.)

Webinject coders offer their products either as public or private webinjects, but some also offer partnerships. Public webinjects are products that are offered to everyone. Private webinjects, on the other hand, are given exclusively to the buyer, meaning that he can resell them and that the coder will not sell this work to any other botmaster. The private webinjects are, of course, more expensive than their public counterparts. In fact, one coder explains in his terms of service that private injects carry a 50% markup when compared to public ones. Some coders also offer a support period where the webinject will be corrected if it does not work as advertised.

Some coders are also interested in partnerships, where they ask for a share of the banking trojan’s profit. In a particular advert we saw, a coder was looking for people with botnets in the UK or Sweden and that were willing to share revenue.

This kind of offering is particularly interesting, as it means that webinject coding is now seen as an essential part of the overall fraud scheme. The fact that some botmasters are now willing to part with some of their earnings in exchange for webinjects leads us to believe that, since these components are now very complex and require constant updates from the coder, sharing profit with their creator makes sense.

As the complexity of the webinject configuration files grows, it is possible to see common patterns amongst them. These patterns allow us to track the different webinject coders, assess their popularity, and find out which banking trojans are using them.

In this section, we will review some of the most prolific webinject coders and where we have seen their creation.

As the complexity of webinjects has grown, so has the need to control them better and monitor the bots that are under their control. Advanced administration panels are bundled along with webinjects to allow botmasters to control the infected bots, collect and search personal information gathered through the webinject, and configure parameters related to the fraudulent operation.

The state of each bot, as well as the user’s bank account information, is shown in the administration panel. The botmaster can then, for example, order an automatic transfer from the user’s account to one of his money mules’ accounts. For these kind of functionalities to exist, the JavaScript code present in the webinject must communicate with the administration panel. When analysing such webinjects, security researchers must interact with the administration panel in order to retrieve information from it. Sometimes, through administration panel interaction, it is possible to retrieve money mule account information, download a mobile component, retrieve images, etc. The administration panel keeps track of the state of each bot and might not allow certain items to be downloaded, such as mobile components, if the state of the bot has not reach a certain point. Thus, during analysis, it is necessary to fully understand the flow of the webinject in order to recreate the different state changes so that all interesting content can be retrieved. Some basic checks are also sometimes performed by the panel before delivering content. For example, when a component is supposed to be downloaded by a mobile, the panel checks that the request has been made by a mobile user-agent before it serves the correct content.

Yummba is a moniker used in underground forums to advertise several different webinject offerings, varying in complexity. It is not clear at this point who is behind these offerings, so we will describe them as a group. This group is selling both simple webinjects that have phish-like features and complex webinjects that encompass mobile components to bypass multi-factor authentication measures. The webinjects come with a panel, which is shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

This group is offering both public and private webinjects. Their public offering is vast and targets numerous financial institutions in Europe, North America and Australia, and includes the necessary schemes to bypass the targeted institutions’ security measures. ATS webinjects are also available for several different banks. There is also a module which can inject content to steal personal information from an array of different banks, called Full Information Grabber (FIGrabber). Figure 14 shows some of the banks that are currently targeted by this framework.

The FIGrabber represents an advancement in webinjects implementing phish-like functionalities. In the past, we have seen webinjects that could be reused and slightly changed to target a different financial institution, but this platform, which targets tens of different banks across different countries, can easily be extended to add other websites. Moreover, there is a unique administration panel that allows the botmaster to manage all of his bots across different regions. This type of webinject appeals to botmasters who have bots scattered in different regions of the world.

As stated earlier, Yummba also bundles mobile components with webinjects targeting banks that implement mTAN as a two factor authentication measure. Interestingly, the first mobile component that was used was Perkele, as advertised in Figure 11, but lately we have seen this group starting to bundle iBanking as opposed to Perkele in certain webinjects [13]. As iBanking offers several features that are not included in Perkele, this is not a surprising development.

We have seen several different banking trojans use the Yummba offering: Qadars, ZeusVM and Neverquest, among others, are using this kit as part of their criminal operations.

Another popular kit is the Injeria webinject backend [14] which comprises webinjects as well as an administrative panel. This kit is easily recognizable as it uses the same distinctive URL parameters to download external scripts.

The last portion of the URL is base64 encoded and, once decoded, gives away the target and the mechanism used by the webinject to attack the targeted institution. Table 3 shows the different tags that were seen while we were monitoring this webinject, and their meaning.

| Tag | Webinject action |

|---|---|

| log-<project_name> | Phish-like inject that asks for additional personal information when the user logs into the targeted website. |

| mob-<project_name> | Webinject contains a mobile component that will be used in an attempt to bypass two-factor authentication sent to the user’s mobile. |

| req-<project_name> | Webinjects using this tag encompass some form of social engineering to bypass non-mobile two-factor authentication systems such as chip-TAN. |

| app-<project_name> | Webinject contains a mobile component that will be used in an attempt to bypass two-factor authentication sent to the user’s mobile. This one might be the evolution of the ‘mob-’ tag. |

Table 3. Different tags that were seen and their meaning.

As can be seen above, this kit also bundles mobile components and social engineering schemes in an attempt to bypass security measures put in place by banks. The fact that the script is retrieved from an external server, as is the case with most of the more advanced webinject kits we studied, means that the coder or the botmaster can quickly update the webinject to adapt to any changing environment or apply a new obfuscation layer to it.

This kit is used by several banking trojans, such as Qadars, Tilon, Torpig and Citadel. The fact that ever more functionalities are included in the webinject offering, and that a growing number of leading banking trojans are using this kit, leads us to believe that this group is currently a dominant player in the webinject coder realm.

There exist several other webinject offerings that are somewhat similar in terms of their functionalities to the others mentioned above. One example is sold by someone using the moniker ‘rgklink’. As with other offerings, this guy is selling a wide array of webinjects targeting different institutions and using varying degrees of sophistication. A free administration panel, called Scarlett, is offered with the purchase of his ATS webinjects. A screenshot is shown in Figure 16.

Table 4 summarizes some of rgklink’s offerings with prices as seen in an advert posted in underground forums in 2013.

| Bank country | Functionalities | Asking price (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Italy (UniCredit.it) | Login/password and token grabber, Jabber alerts | 450 |

| Canada (RBC) | Login/password grabber, additional personal information asked | 450 |

| Germany (Deutsche Bank) | Full ATS | 2,000 |

| Germany (34 targeted institutions) | IP, date, browser, login, password, holder name, balance, account type, account status, email accounts, bank accounts, credit card, expiration date, CVV, date of birth, card address, address list, questions, answers, phone, city, postal code grabber | 2,600 |

Table 4. Offerings and their prices.

As seen above, the price varies according to the webinject functionalities.

Most of the time, webinjects are downloaded by the bot from its C&C server. However, we are now seeing the addition of another layer of indirection: the content downloaded from the C&C is in fact a link to the source of the webinject. Figure 15 is a good example of this.

Downloading the webinjects directly from an external server serves several purposes. First, they can be updated very easily and can also apply different rules depending on which bot is downloading them. Second, some webinjects sold on underground forums are heavily obfuscated, making it very difficult for the botmaster who bought them to change them [15]. Thus, sometimes, the webinject coder will prefer to keep a version on an external server so that he can update it manually when necessary. Finally, it can halt the forensic analysis of compromised systems as the external server might no longer be reachable when the investigation is performed.

There are some webinject frameworks which rely extensively on external server interactions in order to know which content should be injected into a targeted web page. One such framework is constantly communicating with the external server, the admin panel in this case, and constantly receives new JavaScript code that is then inserted into the page. It uses a distinctive function name obfuscation method, includes jQuery, and uses cookies to persist data across web pages. Figure 17 shows an example of the type of communications that occur between the client and the server.

One URL parameter (‘func=’) contains a function name that will then be sent back by the server, appended to the web page and automatically executed. Figure 18 shows the function responsible for requesting new JavaScript from the server and appending it to the current web page.

In this case, the JavaScript functions downloaded from the C&C server are typically only setting different variables or changing the current state of the compromised system. In one of the scripts we studied, the possible states were: wait, block, tan and az. ‘Az’ is short for avtozalivov, the Russian term for ATS. Interestingly, the account information for the money transfer (DropId) is also sent using the same method as described above. Figure 19 shows an example of the variables necessary to tell the webinject kit where to perform the automatic transfer.

This technique is certainly not unique to this kit. In fact, the mule’s account information is rarely seen directly in the webinject – it almost always requires some form of interaction between the bot and the C&C and occurs at the very end of the transfer process. This is understandable, as the cybercriminals wish to keep this information private to prevent it from falling into the hands of security researchers or law enforcement.

Webinjects have evolved dramatically in the past few years. They are now commoditized goods in underground forums. Resourceful botmasters can subcontract webinject coding or buy existing webinjects to target virtually any bank in the world. With several banking trojans now using the same webinject kits, will we see the emergence of ‘the’ webinject kit, just like BlackHole, which was so dominant in the exploit kit scene for so many years? We believe that the answer to this question is yes, and that it has, in fact, already started.

[3] Sood, A. K. et al. Dissecting SpyEye – Understanding the design of third generation botnets. Comput. Netw., 2012.

[4] Sood, A. K.; Enbody, R. J.; Bansal, R. The art of stealing banking information – form grabbing on fire. Virus Bulletin, November 2011. https://www.virusbtn.com/virusbulletin/archive/2011/11/vb201111-form-grabbing/.

[5] Kharouni, L. Automating Online Banking Fraud, Automatic Transfer System: The Latest Cybercrime Toolkit Feature. Trend Micro Research Paper, 2012.

[7] Edwards, D. /packer/. http://dean.edwards.name/packer/.

[8] Lielmanis, E. JS Beautifier. https://github.com/einars/js-beautify.

[11] Klein, A. A La Carte: Criminals Charging Per Feature for Custom Webinjects. http://www.trusteer.com/blog/la-carte-criminals-charging-feature-custom-webinjects.

[12] Krebs, B. A Closer Look: Perkele Android Malware Kit. KrebsOnSecurity. http://krebsonsecurity.com/2013/08/a-closer-look-perkele-android-malware-kit/.

[13] Boutin, J.-I. Facebook Webinject Leads to iBanking Mobile Bot. welivesecurity. http://www.welivesecurity.com/2014/04/16/facebook-webinject-leads-to-ibanking-mobile-bot/.

[15] Klein, A. Webinjects for Sale on the Underground Market. http://www.trusteer.com/blog/webinjects-sale-underground-market.