Posted by Martijn Grooten on Sep 4, 2017

The security community spends a lot of time and effort researching the infrastructure used by spammers to send billions of unwanted and often malicious emails every day – but there is something else spammers need in order to send you their emails: your email address.

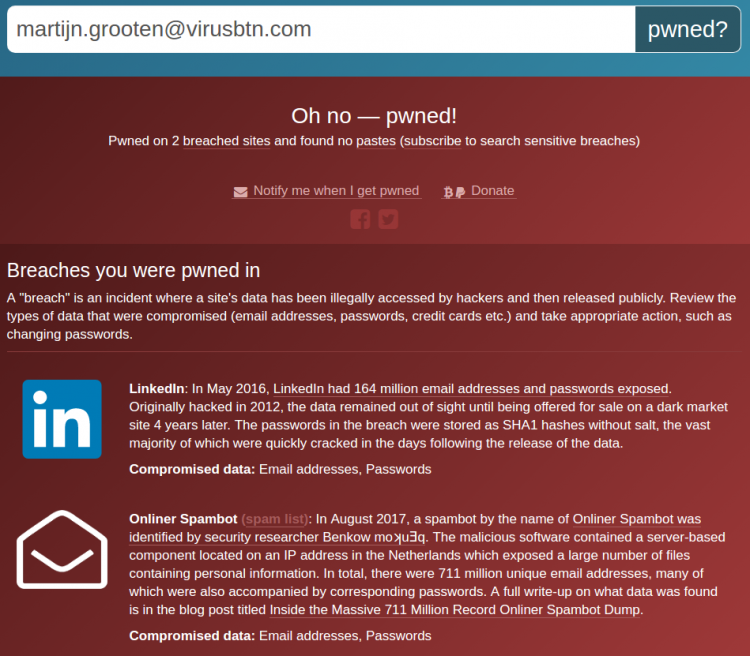

Security researcher Benoît Ancel's recent discovery of various databases used by spammers confirms that they don't have a shortage of email addresses: various files containing in total more than 700 million email addresses were found in an open directory on a server used by the Onliner spambot.

This would make it one of the biggest data breaches ever known, but it is unlikely that the 700 million email addresses are the result of a single breach. Rather, it is more likely that the data was collected from various sources; for instance, the files appear to contain the full list of email addresses stolen in LinkedIn's 2012 breach.

As the data has been uploaded to Troy Hunt's Have I been pwned? service, I was able to check a number of the domains I control. I noticed the absence of recent email addresses (including several 'tagged' addresses known to have fallen into the hands of spammers), as well as the presence of some addresses that have not been used for a decade or more, and several non-existent addresses.

If they could, spammers would send spam only to valid and actively used addresses: invalid or retired addresses often function as spam traps, which in turn feed into IP blacklists and content filters. Hitting a spam trap is a pretty good way of getting most of the subsequent emails in a spam campaign blocked. But once you start sending millions of unwanted emails, such traps are impossible to avoid – so spammers don't bother, and focus on quantity rather than the quality of the emails they send.

This explains why scrapers that look for email addresses on websites and in mailboxes often pick up strings that look like, but aren't, email addresses, such as Message IDs, and why spammers often try common local-parts (such as info@ or john@) on domains, hoping to reach more inboxes. The fact that lists of addresses are actively sold on underground forums where spammers hang out means that is is not unlikely that some of these lists are artificially inflated by the inclusion of fake addresses.

This doesn't make the discovery of the spammer databases any less interesting though, and it is likely that a significant majority of the addresses in the list are actively in use. Usually, if your data appears in a breach some action is recommended, such as changing your password or closing your account. In this case, there is no need for that: if your email address was present in this data breach, it confirms what you no doubt already knew: you are getting spam.

However, the databases discovered by Benoît also feature a second set of data, which includes passwords. In his blog post, Benoît conjectures that these are used by spammers to try and log into SMTP servers to send spam, although the source of this data may still be other breaches: the spammers would just hope that people used the same password for their ISP's SMTP server as they had on some online service. It is a good reminder of the first rule of password security: never reuse passwords.

A VB2017 reserve paper by CERT Poland researchers Maciej Kotowicz and Jarosław Jedynak analyses a number of active spambots. All reserve papers will be presented in Madrid (if not needed as reserves, they will be presented in the 'Small Talks' stream), so don't forget to register for the conference! Last year, at VB2016, Benoît and his then colleague Mehdi Talbi presented a paper on Haka, an open-source language for monitoring, debugging and controlling malicious network traffic.

The security community's praise for Have I been pwned? is well deserved: not only is it an excellent source to help you find which of your data has been breached, Troy's ethics in dealing with what is ultimately other people's data are a great example for the security community.