Telsy, Italy

The information contained herein relates to what I observed throughout 2019 during my analysis and research activities. For my research I originally chose the telecommunications sector because it is a vital component for nearly every existing operating entity. Due to their critical role in today’s society, these organizations are now faced with a multitude of threats in the cyber landscape, ranging from targeted attacks to malicious actions attributable to the criminal or activist world. Adversaries that are targeting this sector have included those suspected by the security industry of operating in support of China, Iran, Russia, Vietnam and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Hacktivism also poses a big threat to ISPs due the involvement of telco companies in government directives and digital regulations.

In 2019 the security community engaged in tracking a new threat trend designed to perform activities commonly known as Domain Name System (DNS) hijacking. These operations were against targets operating in the telecommunications and ISP sector. Since DNS is a fundamental protocol of the Internet, if an adversary succeeds in the hijacking of a DNS infrastructure it could subvert the intended route of the traffic and redirect it to an unintended destination. The primary aim of this type of attack is to facilitate unauthorized access to third-party targets or to enable further malicious activity. When talking about an attack on DNS infrastructures it is usual to identify two distinct groups of victims: public entities or national organizations, ministries, critical infrastructures operating in the energy sector, etc., and DNS registrars, telecommunication companies and ISPs.

Targeted attacks are one of the biggest threats against ISPs and telecom companies in general. Very often, adversaries have the skills, the time and the resources to conduct extensive information-gathering activities in order to compromise a particular network infrastructure. In some cases, these attacks have been characterized by the use of custom and very evasive malware. Table 1 summarizes (in a non-exhaustive manner) what was observed in 2019 regarding the actors and tools involved in targeted attacks against telcos and ISPs.

| Adversary | Tools and malware | Suspected origin |

| APT30 | Evora | China |

| APT41 | RbDoor | China |

| ‘Operation DeadlyKiss’ | DeadlyKiss | China |

| ‘Operation SoftCell’ |

Chopper WebShell Poison Ivy RAT |

China |

| APT34 (a.k.a. OilRig) | RGDoor IIS BackDoor | Iran |

| MuddyWater | NTSTATS | Iran |

| TeamSpy | Commodity malware | Russia |

Table 1: Non-exhaustive summary of actors and tools observed in 2019.

Vector: It is likely that attackers exploited vulnerable external services, VPN credentials and/or used social engineering tricks in order to achieve initial code execution within the victim environment. Once initial code execution has been achieved, we believe with medium-to-high confidence that DeadlyKiss is deployed through self-extracting archives.

Initialization: Once executed, the payload is decrypted using AES-256 in CBC mode and using the MD5 of a hard-coded string as the key. The malware rolls back the installation if Fidelis Endpoint Protection, Carbon Black EDR or AVG Internet Security is found running on the targeted system.

Command and control: Despite the fact that the malware exploits several tricks to remain under the radar, it uses standard HTTP protocol to communicate with command-and-control servers. However, the actor has paid a lot of attention to remaining hidden and to avoiding network-based detection efforts. For example, the malware can be configured to communicate with the outside world only at predefined times (for example, only on Monday from 4:00 PM to 6:00 PM). The malware is able to extract the proxy configuration of the system from Microsoft Internet Explorer settings.

Anti-forensics: The malware is particularly focused on making system analysis very difficult during incident response practices. In detail, the malicious toolkit is able to modify the timestamps of the files relating to it, making it difficult to create timelines during the events reconstruction phase.

Anti-analysis: The malware implements various techniques and strategies aimed at discouraging and making static and dynamic analyses particularly difficult. Among the most interesting are code obfuscation and string encryption.

Code obfuscation: the code obfuscation mechanism put into place by the actor is very effective in discouraging and making both static and dynamic analysis particularly difficult and is also very effective in complicating code matching, binary diffing and code‑based signature generation practices.

This is because the technique implemented is able to break long sequences of opcodes, change the control-flow graphs and modify the code instructions at a high level. Its operating methodology can be summarized through the following steps:

The following is an example of an obfuscated code snippet:

v3 = GetLastError() + 41;

v22 = 270 - v3;

if ( ( signed int ) v3 > 48 ) {

if (v3 == 600) {

div(919,13);

} else if (v3 == 712) {

div(810,34);

} else if (v3 == 390) {

div (780,22);

} else {

switch(v3) {

case 610:

div(400,34);

case 690:

div(780,43);

default:

div(890,23);

}

}

[REDACTED]

The returning value of an API call and subsequent calls to garbage functions are used to complicate the understanding of the original code; this normally suggests the use of opaque predicates but here all fragments of the obfuscated code land on more junk code, which with particular conditions eventually lands back at the original code.

String encryption: The malware encrypts all of the strings to be used during its workload. This makes it more difficult to have some strings as a reference in order to better understand the general nature of the executable. Generally speaking, strings are decrypted making use of RC4 algorithm and the first bytes of the encrypted strings as key. The following pseudo-code reports a series of instructions that could be used to decrypt a DeadlyKiss internal string.

s = "WuYrfU2FsdGVkX1+N/vX/GsmXZkN6uJeK3UKM";

key = s[:5];

ctext = s[5:];

w = RC4.new(key);

print w.decrypt(ctext);

Generally speaking, DeadlyKiss is to be considered an advanced and robust malicious implant. Actor spent a lot of time in the care of its code and limited its diffusion in order not to compromise the very low detection rates that the malware presented at the time of the original report.

From 2016 to 2019 the variants of this malware family remained virtually the same. My first internally developed YARA rule based exclusively on internal strings found positive matches in versions that were temporally very distant from each other.

However, despite some difficulties described earlier in code-based rule generation, it is possible to use specific references such as particular imports and XOR cycles.

For example, the IsUserAnAdmin function is imported through its corresponding hex value (see Figure 1) and there are XOR cycles we can use to generate useful threat-hunting rules.

Figure 1: The IsUserAnAdmin function is imported through its hex value.

Figure 1: The IsUserAnAdmin function is imported through its hex value.

The rule obtained looks similar to the following:

rule APT_DeadlyKiss_81893_23211 : APT {

meta:

description = "Detects DeadlyKiss based on imported IsUserAnAdmin function and XOR"

author = "Emanuele De Lucia"

strings:

$export_1 = "DllRegisterServer" ascii

$export_2 = "ServiceMain" ascii

$export_3 = "DllUnregisterServer" ascii

$export_4 = "DllCanUnloadNow" ascii

$isuseradmin = { A8 02 00 }

$shell = "SHELL32.dll" ascii

$xor_x32 = { C1 E9 02 32 48 FC 32 08 }

$xor_x64 = { C1 E8 02 32 44 0A FC 32 04 0A }

condition:

( uint16 ( 0 ) == 0x5A4D and

( $isuseradmin and $shell and 1 of ( $export_* ) and ( $xor_x32 or $xor_x64 ) ) )

}

Vector: Variants of Evora are spread both by spear-phishing attacks and by exploiting external vulnerable services and/or weak credentials in order to obtain a first code execution within the victim environment.

Initialization: The malicious toolkit is composed of a loader DLL with an embedded executable within its .data section. The embedded executable is extracted and runs in memory. If the -Install function is called during the initialization the loader will create a new service in order to achieve persistence.

Command and control: Evora has been designed to communicate with command-and-control servers using a webmail service provider. Some samples observed during 2019 used a webmail service provided by Netvigator, a Chinese telco company. Netvigator uses Zimbra as a mail server that provides for access to mail accounts through SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol).

The following is an example of an AuthRequest SOAP request sent to https://em.netvigator[.]com/service/soap/AuthRequest by an Evora implant:

<soap:Envelope xmlns:soap="http://www.w3.org/2003/05/soapenvelope"><soap:Header><context xmlns="urn:zimbra"><nosession/><userAgent name="Zimbra Desktop" version="Windows"/><via>REDACTED</via></context></soa p:Header><soap:Body><account:AuthRequest xmlns:account="urn:zimbraAccount"><account:account by="name">REDACTED</account:account><account:password>REDACTED</account:passw ord><account:prefs/><account:attrs/></account:AuthRequest></soap:Body></soap: Envelope>

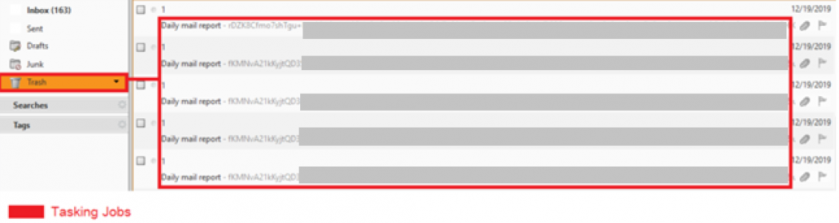

The configuration part, once decrypted, contains a username and password to validate a communication session. Once the malware is successfully authenticated, it performs a series of actions in order to retrieve tasks to be executed in the context of the victim system. After having performed a SyncRequest, it collects all items in the Trash folder of the mailbox, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Tasks and command responses to be parsed and decrypted as observed within a replicated environment.

The response to this query contains a JSON object with the contents of any item. The tasking messages are composed of two parts: the task information within the message body and the command body in an attachment, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Task information and command body of an Evora tasking message as observed within a replicated environment.

Figure 3: Task information and command body of an Evora tasking message as observed within a replicated environment.

The task information is responsible for providing data such as the command ID to be executed and victim information such as the IP and MAC address. Any data related to tasking and commands executed is encrypted through AES-256 in CBC mode. The configuration data, embedded within the .data section of the executable, contains a crypto master key as well. This key is in turn used in a key-based password generation algorithm to generate a new key for the AES-based encryption scheme. Once executed, the malware responds to each task, uploading another mail attachment to the same Trash folder, which contains the command response.

The extracted command ID list is shown below (in numerical order):

| Task | Action |

| 0x10 | Sends to the actor the current running configuration |

| 0x11 | Updates the current configuration |

| 0x12 | Loads a new specific DLL module from disk |

| 0x13 | Reads and sends the content of a file |

| 0x14 | Updates the content of a file |

Anti-forensics: For the analysed version of Evora there seem to be no anti-forensics tricks.

Anti-analysis: Evora uses the ‘IsDebuggerPresent’ API call.

LZARI compression is not common in malware. It’s mainly used in PlayStation 2 emulators where it is used to compress games‑related files. A YARA hunting rule focused on this aspect can be very effective in finding variants of this family. An example of such a rule is as follows:

rule APT30_Evora_LZARI_8923_23 : CHINESE APT GROUPS {

meta:

description = "Detects LZARI code to detect APT30/Evora implants"

author = "Emanuele De Lucia"

tlp = "white"

company = "Telsy SpA"

strings:

$hex1 = { 66 0F 7F 84 24 60 28 01 00 48 89 7C 24 30 89 7C 24 38 89 BC 24 8C D4 00 00 }

$hex2 = { C7 84 24 5C 28 01 [5] A1 ?? ?? ?? ?? 89 94 24 24 28 01 00 89 84 24 38 28 01 00 }

condition:

(uint16(0) == 0x5A4D and filesize < 900KB and ( 1 of ($hex*)))

}

In early 2019 I was alerted to a compromise that occurred against the public-facing website of an ISP operating in the Middle East.

Although this news by itself was not particularly interesting, it acquired a lot more significance when variants of the ‘TwoFace’ webshell were identified within the victim website in conjunction with variants of the IIS RGDoor backdoor. At the time, this combination was consistent with cyber operations commonly conducted by the threat actor known as APT34 (a.k.a. OilRig), and after this event, the security community updated the group’s TTPs by adding ISPs to its potential targets.

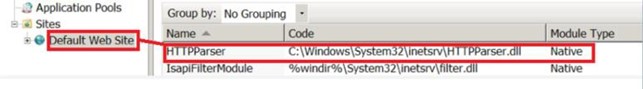

Vector: IIS RGDoor is installed within the target system by exploiting vulnerable public-facing web servers. The TwoFace webshell is used to get commands executed in the context of the victim service. IIS RGDoor is then loaded as a native extension module, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Module configuration section of an IIS server infected by RGDoor.

Figure 4: Module configuration section of an IIS server infected by RGDoor.

By observing a potential infection during its workload, a spawning of command shells from the webserver process can be noted while the malware performs operations aimed at collecting information from the network environment. This feature can be used in order to find and exploit vulnerable services and to pivot to internal nodes.

Targeted attacks against ISPs and companies operating in the telco sector should be taken very seriously. The greatest threats are represented by actors looking for customer data, for monitoring capabilities and for exploitation of a valuable infrastructure in order to conduct espionage operations against third parties.

Indeed, the compromise of an ISP network could allow further intrusion activities as it could allow the actor to re-route network traffic and/or communications to actor-controlled malicious infrastructure.

Finally, the amount of data that could be collected by compromising the network of an ISP is enormous and could be used in various intelligence activities as well as in espionage activities against individuals, entities and organizations.

[1] DeadlyKiss: Hit one to rule them all. Telsy discovered a probable still unknown and untreated APT malware aimed at compromising Internet Service Providers. Telsy. September 2019. https://www.telsy.com/deadlykiss-malware/.