Prismo Systems, USA

According to OWASP’s top 10 web application security risks, injection flaws are one of the topmost risks and have ruled as such for a decade. Injection flaws include SQL, NoSQL, OS command and LDAP injection techniques. Threat actor groups such as Axiom and Magic Hound have been observed using SQL injection to gain access to systems. The research community has extensively discussed exploitation details for SQL, NoSQL, OS command and LDAP injection exploits. This paper will dive into the technical details of a novel detection algorithm that can be used to detect these injection exploits.

Our detection algorithm leverages code flow analysis. Injection attacks such as SQL, NoSQL, OS command and LDAP injection exploits insert additional code, which leads to a change in the legitimate code of an application. The algorithm makes use of abstract syntax trees (AST), program dependency graphs (PDG) and SQL parse trees to compute the changes in the original code caused by injection-based exploits.

The detection algorithm discussed in this paper provides an inherent advantage. It not only detects SQL, NoSQL, OS command and LDAP injection exploitation by a threat actor but also automatically identifies the vulnerable section of the application code, which will help application developers in patching the code, preventing further exploitation.

Web injection exploitation has ruled as the top web application vulnerability for a decade. Injection flaws [1] include SQL, NoSQL, OS command and LDAP injection techniques. Exploitation occurs when untrusted data is sent to an interpreter as part of a command or query.

OS command injection is an exploitation technique in which the goal is the execution of arbitrary commands on the host operating system via a vulnerable application. OS command injection exploitation is operating system-independent, i.e. it can happen on Windows or Linux.

In the case of SQL injection exploitation, malicious SQL statements are inserted via the methods which accept a user’s or external inputs such as GET, POST, HTTP headers, lambda functions, etc. These malicious SQL queries are executed and perform malicious activities such as dumping the database contents, etc. to a location determined by the attacker. Threat actor groups such as Axiom [2] and Magic Hound [3] have been observed using SQL injection to gain access to systems. Injection attacks such as SQL injection exploitation can lead not only to malicious access to the database but also to the installation of malicious code such as web shells [4]. Databases such as MongoDB support the use of JavaScript functions for query specifications and map/reduce operations. Since MongoDB databases (like other NoSQL databases) do not have strictly defined database schemas, using JavaScript for query syntax allows developers to write arbitrarily complex queries against disparate document structures. If these queries accept input from HTTP methods and headers such as GET, POST, Cookies, User-Agent, etc. then these JavaScript functions can be prone to NoSQL injection exploitation [5]. Besides SQL and NoSQL databases, threat actors can also construct a malicious XPath expression or XQuery to retrieve the data from an XML database.

Injection attacks such as SQL, NoSQL and OS command injection exploits add additional code, which leads to a change in the legitimate code of the application. This change in the legitimate code is reflected in the abstract syntax tree (AST), program dependency graph (PDG) and SQL parse tree. In the first section of this paper we will take examples of SQL, NoSQL and OS command injection exploits and show the changes in the AST, PDG and SQL parse tree due to the exploits. These changes in the code are the fundamental principle of the detection algorithms used to detect SQL, NoSQL and OS command injection, which are discussed in the subsequent sections.

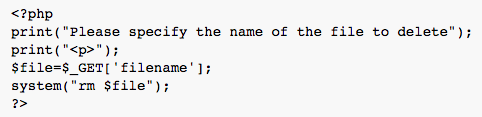

Figure 1 shows code that is vulnerable to OS command injection attack.

Figure 1: Code vulnerable to OS command injection.

Figure 1: Code vulnerable to OS command injection.

The code takes the name of the file which is to be deleted from the value field of the GET method. In the subsequent line of code the PHP program execution function system() takes the value of the file name from the data field of the GET method and invokes the bash command rm to delete the file.

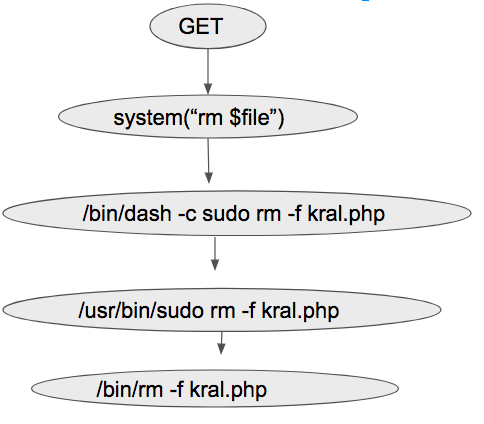

Let’s assume that the file shown in Figure 1 is on a server with IP address x.x.x.x as test.php. hxxp://x.x.x.x:8000/test.php?filename=kral.php is an example of the legitimate input. It takes input as kral.php from the data field of the GET method and deletes the file kral.php from the folder. The dynamic call graph which captures the execution flow, i.e. control and data dependency, is shown in Figure 2. The dynamic call graph captures the control and data flow not only when the code is executed by a PHP application but also when the OS commands are executed by the PHP application. The nodes in the graph denote the statement, predicates, OS events and system calls. The edges denote the parent-child relationship.

Figure 2: Dynamic call graph of the legitimate request.

Figure 2: Dynamic call graph of the legitimate request.

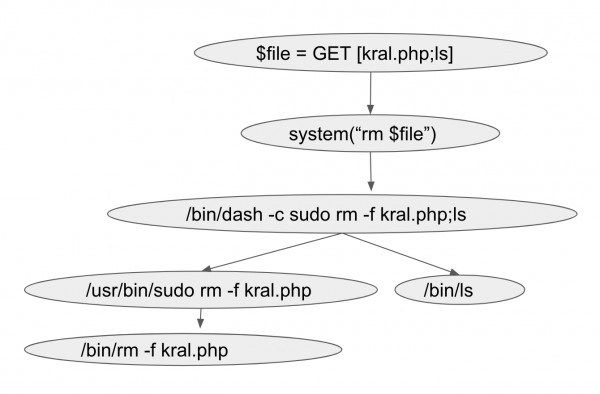

http://x.x.x.x:8000/test.php?filename=kral.php;ls is an example of an OS command injection exploit. In the request, the threat actor has injected the OS command ls with the value of the GET method kral.php.

Figure 3 shows the dynamic call graph when the exploit is sent to the vulnerable application. As can be seen, a new node with the value /bin/ls – the injected OS command – is spawned. The value of this additional node can be traced up the graph and is the same as the command ls that was appended to the value field of the GET method.

Figure 3: Dynamic call graph with OS command injection exploit.

Figure 3: Dynamic call graph with OS command injection exploit.

The algorithm used to detect the OS command injection attack not only makes use of application‑level hooks but also captures system calls and other OS events to generate the dynamic call graph. As part of the first step, the dynamic call graph traces the data passed to those methods that accept user or external inputs such as GET, POST, Cookies, HTTP headers, etc. The subsequent child processes (which can be OS events or invocation of the system calls spawned due to the execution of a program execution function such as eval(), passthru(), shell_exec(), system(), proc_open(), expect_open() or ssh2_exec()) get captured in the dynamic call graph.

Once the dynamic call graph has been generated, the algorithm uses the graph to check whether the exact name of the command line argument of any of the child processes of the program execution functions that are being spawned by the OS command is same as the value or appears in the part of the value passed to the methods that accept user inputs such as GET, POST, Cookies & HTTP headers. If the condition is found to be true, an alert for OS command injection vulnerability is raised. The algorithm is independent both of the application which is being executed and of the operating system on which the algorithm is running, hence it helps to identify both known and zero-day OS command injection vulnerabilities.

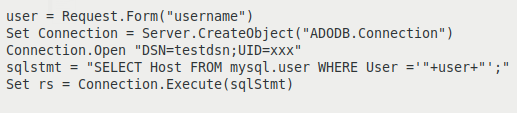

Figure 4 is an example of code that is vulnerable to SQL injection attack. The code accepts the username from the HTTP request in the variable user. The variable user then acts as an input to the SQL query sqlStmt. In the subsequent part of the code, the query gets executed by the function Connection.Execute().

Figure 4: Code vulnerable to SQL injection.

Figure 4: Code vulnerable to SQL injection.

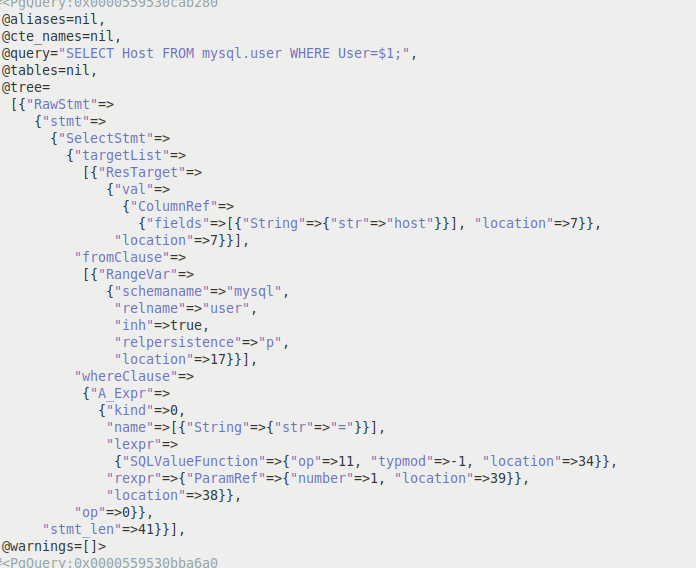

SELECT Host FROM mysql.user WHERE User ='abhi'; is an example of a legitimate SQL query executed by the application. The legitimate query sent to the database is defined in the application and the value of the variable user as 'abhi' is taken from the value field of the methods which accept user input such as GET, POST, etc. Figure 5 shows the PostgreSQL parse tree [6] of the normalized query.

Figure 5: PostgreSQL parse tree of the valid normalized query.

Figure 5: PostgreSQL parse tree of the valid normalized query.

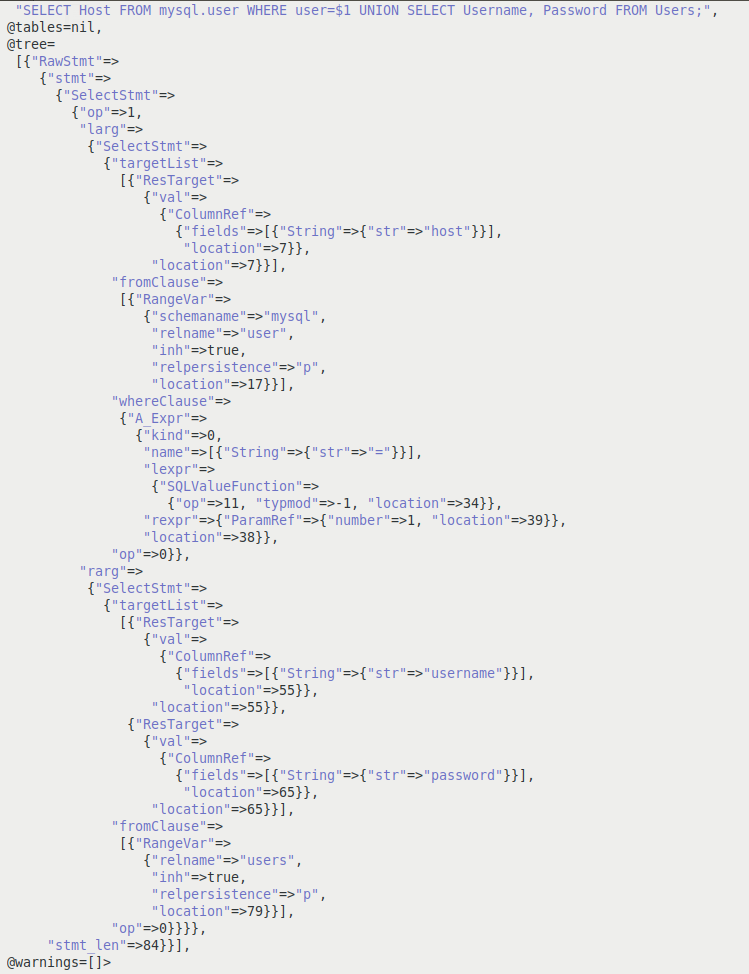

In the case of an SQL injection exploitation, a threat actor will insert a malicious SQL query along with a value into the methods that accept user or external inputs (such as GET, POST). This malicious query will be executed by the application along with the legitimate query. Explaining it with an example, if the threat actor injects the malicious SQL query UNION SELECT username, Password FROM Users by appending it to the value of the variable user 'abhi', the query that gets executed by the application becomes SELECT Host FROM mysql.user WHERE user= 'abhi' UNION SELECT username, Password FROM Users ;.

A PostgreSQL parse tree of the normalized SQL query with the injected SQL query is shown in Figure 6. As can be seen in Figure 6, an additional node is created in the PostgreSQL parse tree as a result of the inserted SQL command.

Figure 6: PostgreSQL parse tree with the injected SQL command.

Figure 6: PostgreSQL parse tree with the injected SQL command.

SQL injection exploits will introduce an additional SQL query to the database. This injected SQL query will be reflected as an additional node in the query parse tree of the legitimate normalized SQL query.

The algorithm used to detect the SQL injection attack makes use of application-level hooks to construct a program dependency graph (PDG). The PDG captures the flow of data and control from methods which accept external or user input such as GET, POST, Cookies, etc. to the functions which execute the SQL query such as mysql_query(), mysql_db_query(), mysql_unbuffered_query(), pg_execute(), pg_query(), pg_query_params(), pg_prepare(), pg_send_query() and pg_send_query_params(). Once the PDG is generated, it is used to identify the legitimate SQL queries which are the sink for the value from the methods which accept user or external input such as GET, POST, etc. These SQL queries are the parameters for the SQL query execution functions and are stored as the parse tree. Any injected malicious SQL query will be reflected in an additional node in the parse tree of the normalized legitimate SQL query. For every database access, the parse tree of the executing query is compared with the parse tree of the legitimate query. If there is an additional node in the parse tree of the executing SQL query, then it gets matched with the value or with the part of the value passed to the methods that accept user or external input. In the case of a match, an alert for SQL injection is raised.

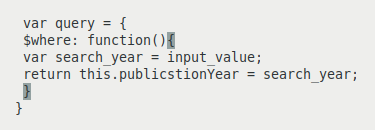

A NoSQL database provides the ability to run JavaScript in the database engine to perform complicated queries or transactions. Figure 7 shows an example of a JavaScript query. The query accepts external input in the variable search_year and then searches in the database for all the publications that match the values of the search year.

Figure 7: JavaScript query.

Figure 7: JavaScript query.

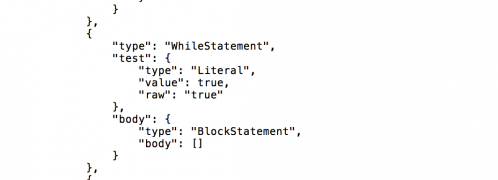

A legitimate GET request will appear in the format http://server.com/app.php?year= 2015. The input ‘2015’ will act as an input value for the variable search_year, and the query will return the publications which were published in the year 2015. An example of a NoSQL injection attack is http://server.com/app.php?year=2015;while(true){}. The exploit injects the NoSQL code while(true){}. This injected code will be executed by the database and will cause the database to enter into an infinite loop, leading to a denial of service attack. If we construct abstract syntax trees [7] for the legitimate JavaScript function and the function with injected NoSQL code and compare them, as can be seen in Figure 8, NoSQL injection leads to the addition of a new node.

Figure 8: Addition in the AST of the legitimate JS function.

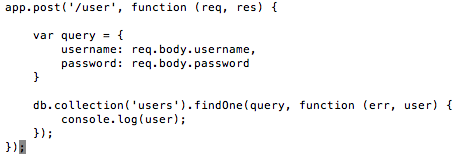

Besides using JavaScript to draft queries, JSON format is also used to send queries to NoSQL databases and is prone to NoSQL injection exploitation. Figure 9 shows an example of the vulnerable code [8] which crafts a query in JSON format. The code accepts the value of the variables username and password from the POST method, and the query is sent to the database by invoking the findOne function.

Figure 9: Code vulnerable to NoSQL injection exploitation.

If a user enters ‘admin’ as the value for the variable username, and ‘password’ as the value for the variable password, the JSON query which is sent to the database will be as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: JSON query sent to the database.

Figure 10: JSON query sent to the database.

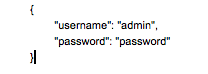

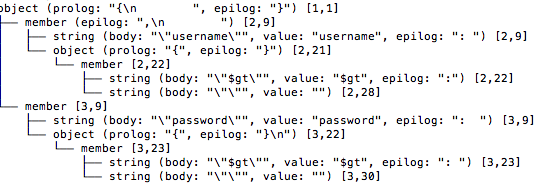

The AST of the legitimate JSON query, shown in Figure 11, will always have two members.

Figure 11: AST of the legitimate JSON query.

Figure 11: AST of the legitimate JSON query.

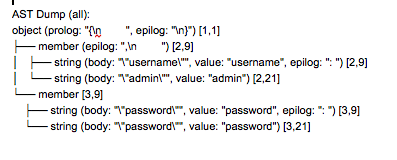

Taking an example of a malicious query, a threat actor can enter {"$gt":" "} as the value for the variables username and password, which will lead to the query shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Malicious query due to injection.

Figure 12: Malicious query due to injection.

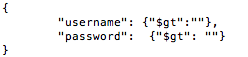

$gt will select the documents which are greater than “ “. This statement will always be true, and the threat actor will successfully be able to authenticate. If we construct the AST of the modified JSON query due to the NoSQL injection exploit (Figure 13), we can see that additional nodes are introduced.

Figure 13: AST of the NoSQL exploit JSON query.

Figure 13: AST of the NoSQL exploit JSON query.

NoSQL databases accept queries in the form of JSON or JavaScript functions. NoSQL injection exploits will introduce additional JavaScript code or a JSON query. This injected code or JSON query will show up as additional nodes in the abstract syntax tree of the legitimate normalized JavaScript code or JSON query.

The algorithm used to detect a NoSQL injection attack makes use of application-level hooks to monitor functions such as mapReduce(), find(), findOne(), findID() and the where operator. These functions accept queries in the form of NoSQL JavaScript functions or as JSON arguments which get executed in the NoSQL database. Once the functions are hooked in an executing application, their arguments are used to identify the JavaScript code or queries in JSON which are executed by the database. A program dependency graph is used to identify the JS functions or JSON query which accepts user or external input from methods such as GET, POST, etc. If there is a flow of data from such methods to these JavaScript functions or a JSON query, then the abstract syntax tree (AST) of the legitimate JS function or JSON query is computed. In the case of a successful NoSQL injection exploitation, the AST of the legitimate JavaScript code or JSON query will change. NoSQL exploitation will introduce additional nodes to the legitimate AST. For every database access, the AST of the executing JS function or JSON query is compared with the legitimate JS function or JSON query. If there is an additional node in the AST of the executing JS function or JSON query it is compared with the value or with the part of the value passed to the methods such as GET, POST, Cookies, User-Agent, etc. In the case of a match, an alert for NoSQL injection is raised.

XPath injection [9] exploitation is similar to SQL injection exploitation with the difference being that, in the case of SQL injection exploitation, malicious SQL queries are sent to the database and, in the case of XPath injection exploits, malicious XPath expressions are sent to the XML databases which store the data. These malicious XPath expressions can then be used to modify or delete the data stored in the XML database.

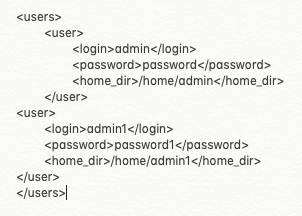

Figure 14: An XML file storing login and password.

Figure 14: An XML file storing login and password.

Figure 14 shows an example of an XML file storing login and password details. Figure 15 shows an example of code [9] vulnerable to the XML path injection vulnerability. The code accepts the user input username and password from the GET method and passes the variable xlogin to XPathExpression. The code then creates a new instance of the Document which, in the subsequent code xlogin.evaluate(d), is used to validate the username and password stored in the XML file with the username and password in the variable xlogin. In the case of a valid username and password, authentication succeeds.

Figure 15: Code vulnerable to XPath injection exploitation.

Figure 15: Code vulnerable to XPath injection exploitation.

If a threat actor enters 'admin' or "=" for the username and " or "=" for the password, the XPath expression becomes

//users/user[login/text()='admin' or "=" and password/text() = " or "="]/home_dir/text()

The condition or "=" is always true and allows the threat actor to log onto the system without authentication.

The algorithm used to detect an XPath injection attack makes use of application-level hooks to construct a program dependency graph (PDG). The PDG captures the flow of data and control from methods which accept external input such as GET, POST, Cookies, etc. to the functions such as xpath.compile() which construct the XPath expression, and functions which execute XQuery such as xdmp:eval(), xdmp:value(), fn:doc() and fn:collection(). Once the PDG is generated, it is used to identify the legitimate XPath expression or XQuery which accepts data from the methods that take user input such as GET, POST, Cookies, etc. Any injected malicious XPath expression or XQuery will show up as a change in the abstract syntax tree of the normalized legitimate XPath expression or XQuery. For every database access, the AST of the executing XPath expression or XQuery is compared with the legitimate XPath expression or XQuery. If there is an additional node in the AST of the executing XPath expression or XQuery, then this change in the AST is matched with the value or with the part of the value passed to the methods which accept user inputs such as GET, POST, Cookies, etc. In the case of a match, an alert for XPath injection is raised.

LDAP injection is another injection technique which has been used by threat actors to extract information from the LDAP directory. LDAP filters are defined in RFC 4515. RFC 4256 allows the use of the following standalone symbols as two special constants:

- (&) -> Absolute TRUE

- (|) -> Absolute FALSE

In the case of LDAP injection exploitation a threat actor can inject a malicious filter. If the web application does not sanitize the query, the inserted filter will be executed by the threat actor, which can lead to providing additional information to the threat actor, or to bypassing access control.

![]() Figure 16: Legitimate LDAP query filter in an application.

Figure 16: Legitimate LDAP query filter in an application.

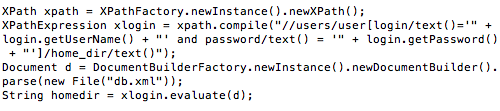

Figure 16 shows an example of an LDAP filter in an application which accepts the value of the variables username and password from the user-supplied input methods such as GET, POST. If the value of the variable username is abhi and the value of the variable password is pass, then the parse tree of the LDAP filter is as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17: Parse tree of the legitimate LDAP filter.

Figure 17: Parse tree of the legitimate LDAP filter.

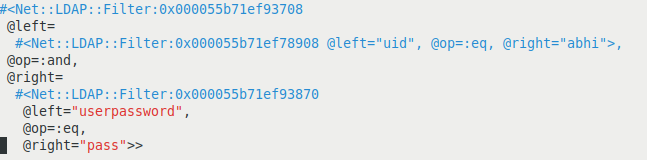

In an application, the LDAP filter will remain the same, only the value of the user input variables to the LDAP filter will change. In the case of an LDAP injection exploitation, a threat actor can introduce a malicious LDAP filter which will modify the legitimate LDAP filter and will be executed by an application. Explaining it with an example, for the LDAP filter shown in Figure 16, if a threat actor enters abhi)(&)) as the value of variable username and userpassword is left empty, the modified LDAP filter query is as shown in Figure 18.

![]()

Figure 18: LDAP filter due to the injection attack.

In the modified filter, only the first filter is processed by the LDAP server – that is, only (&(uid=abhi)(&)) is processed. This query is always true, so the threat actor will be able to authenticate without having a valid password. This is also reflected in the parse tree of the modified query shown in Figure 19.

![]()

Figure 19: Parse tree of the modified query.

In the case of LDAP injection exploitation, if a threat actor introduces a malicious filter, then it will be reflected by a modification in the parse tree of the legitimate filter query.

The algorithm used to detect LDAP injection attacks makes use of application hooks to monitor the functions which execute LDAP filter queries such as ldap_search(), ldap_search_st(), ldap_search_ext() and ldap_search_ext_s(). Hooks to these functions help to identify the legitimate LDAP filter queries which will be executed by an application. Application hooking is also used to generate a program dependency graph which captures the flow of data and control from methods which accept user inputs such as GET, POST, etc. to the functions which execute LDAP filter queries. Once the program dependency graph has been generated, it is used to identify the legitimate LDAP filter queries in an application which can accept user input from methods such as GET, POST, etc. If there is a flow of data from methods such as GET, POST, etc. to the LDAP filter queries, the parse tree of the normalized LDAP filter query is computed and stored. For every access to LDAP, the parse tree of the normalized executing LDAP filter query is compared with the parse tree of the normalized legitimate LDAP filter query. In the case of a mismatch between the parse trees, the values from methods such as GET, POST, etc. are checked to validate if the mismatch is due to the value field. If the validation is found to be true, an alert for LDAP injection exploitation is raised.

The algorithm used to detect NoSQL, SQL, XPath, OS command and LDAP injection attacks makes use of application-level hooks and monitoring of systems calls. Injection attacks such as SQL, NoSQL, OS command and LDAP injection exploits add additional code which leads to a change in the legitimate code of the application. The algorithm used to detect web injection-based exploitation makes use of abstract syntax trees (AST), program dependency graphs (PDG) and query parse trees to compute the changes in the original code due to injection-based exploits. The computation of changes in the code is done for every access to the database and invocation of program execution functions. If there is any deviation from the original code which is identified by changes in the AST, PDG, SQL parse tree or LDAP parse tree, it is checked to determine whether the deviation is due to the value or part of the value passed to the methods which accept user input such as GET, POST, Cookies, User-Agent, etc. In the case of a verification, an alert for injection exploitation is raised.

The algorithm used to detect injection-based exploitation has the following inherent advantages:

These factors make the algorithm a recommended solution to detect NoSQL, SQL, LDAP, OS command, XPath and XQuery injection exploitation.

[1] Top 10-2017, Top 10. https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Top_10-2017_Top_10.

[2] Exploit Public-Facing Application. https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1190/.

[3] SQL Map. https://attack.mitre.org/software/S0225/.

[4] Compromised Web Servers and Web Shells – Threat Awareness and Guidance. https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/alerts/TA15-314A.

[5] NoSQL Injection. https://ckarande.gitbooks.io/owasp-nodegoat-tutorial/content/tutorial/a1_-_sql_and_nosql_injection.html.

[6] libpg_query. https://github.com/lfittl/libpg_query/blob/10-latest/README.md#resources.

[7] ECMAScript parsing infrastructure for multipurpose analysis. http://esprima.org.

[8] NoSQL injection in Mongodb. https://zanon.io/posts/nosql-injection-in-mongodb.

[9] XPath Injection. https://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/643.html.

[10] JSON -AST. https://github.com/rse/json-asty.

[11] LDAP Injection & Blind LDAP injection in Web Application. https://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-europe-08/Alonso-Parada/Whitepaper/bh-eu-08-alonso-parada-WP.pdf.

[12] LDAP Filter Parser. https://www.rubydoc.info/github/ruby-ldap/ruby-net-ldap/Net/LDAP/Filter/FilterParser.