Sophos, Australia

The popular macOS bundleware exemplar presented in this research employs some surprising techniques. Not only does it employ anti-debugging, strings/API encryption and Mach-O runtime decompression techniques, its developers went as far as embedding a full backdoor component into the installer, granting it capabilities that extend way beyond what one might expect from a piece of installation software.

In this research, we’ll dive into the installer’s Mach-O binary to demonstrate how it piggy-backs on ‘non-lazy’ Objective-C classes, the way it dynamically unpacks its code section in memory and decrypts its config. An in-depth analysis will reveal the structure of its engine and the full scope of its hidden backdoor capabilities, anti-debugging, VM evasion techniques and other interesting tricks that are typical in the Windows malware scene, but which aren’t commonly found in the unwanted apps that claim to be clean, particularly on the Mac platform.

This paper will reveal practical hands-on tricks used in Mach-O binary analysis under a Hackintosh VM guest, using LLDB debugger and IDA Pro disassembler, along with a very interesting marker found during the analysis.

DISCLAIMER: the software vendor won’t be named; this research is entirely focused on technical aspects of the reverse-engineered software.

The user experience interacting with Mac applications normally starts from the download and installation process. In their quest to make this experience positive, many developers turn to application installation platforms that promise enhanced installation analytics, optimized footprint, and a guaranteed smoothness of installation.

What happens is that some of the application installation platforms bundle the title application with third-party software, such as adware or browser toolbars, leading to a setup that the end-user might find unwanted.

The word ‘unwanted’ is the key here. Once the target application is installed, users often encounter undesirable consequences, such as installed browser hijackers that modify the search engine for their web browser. In some cases, the highly questionable Mac removers might prompt the user to pay for the removal of non-existent threats.

To protect customers, for many years Sophos has detected such bundleware under the tag ‘potentially unwanted application’.

Detecting such applications is never a problem, as they normally belong to a league that is different from malware – it’s a way more simplistic breed, so to speak.

That’s not always the case though.

The fairly popular bundleware exemplar described in this paper employs techniques that any seasoned threat researcher will find rather amusing. Not only does it employ anti-debugging,

strings/API encryption, runtime decompression and VM evasion, its developers went as far as embedding a full backdoor component into the installer, granting it capabilities that extend way beyond what one might expect from a piece of installation software.

The power given to the installer practically enables full control over the target system. Even if this was done so that the company behind it would have ‘advanced analytics’ or the ability to push any third-party software it wants, what happens if this power is abused?

Boasting ‘tens of millions of downloads’ per day (whether this is true or not), this particular bundleware has potential access to a large number of Macs around the world. Given the amount of power it aggregates, it is a matter of duty for security folks to take a closer look at this software.

The bundleware described in this post is a Cocoa application – an application built with the AppKit framework [1]. It is distributed as an application bundle. Among other resources contained in the bundle, the Info.plist file (an XML file) contains a key CFBundleExecutable that points to the main executable located in the MacOS folder.

From sample to sample, the name of the main executable varies. For example, it can be named radiosurgical or Herculid.

The digital signature used to sign the app varies constantly. At one point, it was signed by ‘Owen Bell’; in other cases, it was signed by ‘RuiQing Software Technology Beijing Inc.’; in September – October 2018, the app was signed by ‘AVSoftware EOOD’.

Compiled as Mach-O (the native executable file format for macOS), the main executable relies on Objective-C runtime libobjc.dylib.

When the kernel first loads it, it makes sure it’s a valid Mach-O file, and then examines its mach_header structure. Next, it loads the dynamic linker to load all the shared libraries that the main executable links against.

The dynamic linker thus initializes the Objective-C runtime, and then calls the program’s main() function.

What appears unusual, though, is that the entry point starts from garbage bytes – that is, the entry point has no valid code to execute:

__text:0000000100001150 start db 4

__text:0000000100001151 db 4Ah ; J

__text:0000000100001152 3 db 3Eh ; >

With no valid code at the entry point, how is it executed without crashing?

The answer lies in the concept of non-lazy (‘eager’) and lazy (‘on-demand’) implementation of Objective-C classes.

Non-lazy classes are realized when the program starts up. These classes will always implement the +load method.

Contrary to that, lazy classes (classes without the +load method) do not have to be realized immediately, but only when they receive a message for the first time (hence the term ‘lazy’).

Let’s check out Objective-C runtime’s own source [2] found in the objc-runtime-new.mm file.

The snippet below realizes the non-lazy classes, retrieved with the _getObjc2NonlazyClassList() call:

// Realize non-lazy classes (for +load methods and static instances)

for (EACH_HEADER) {

classref_t *classlist = _getObjc2NonlazyClassList(hi, &count);

for (i = 0; i < count; i++) {

realizeClass(remapClass(classlist[i]));

}

}

Looking at the source of the Objective-C runtime [3] in objc-file.mm, one can see that the _getObjc2NonlazyClassList() function collects non-lazy classes from the __objc_nlclslist data section:

// function name | content type | section name - 'nl' stands for non-lazy

GETSECT(_getObjc2NonlazyClassList, classref_t, "__objc_nlclslist");

The __objc_nlclslist data section of the main binary is very small. It enlists only two non-lazy classes: ListedUpaithric and __ARCLite__:

__objc_nlclslist:0001000692C8 __objc_nlclslist segment para public 'DATA' use64

__objc_nlclslist:0001000692C8 dq offset _OBJC_CLASS_$_ListedUpaithric

__objc_nlclslist:0001000692D0 dq offset _OBJC_CLASS_$___ARCLite__

__objc_nlclslist:0001000692D0 __objc_nlclslist ends

The ListedUpaithric name, like many other class names, is random. For example, in another sample this class is called HoundingHusky.

Both classes above have the +load method, and that method is called to realize both classes.

The +load method of the ListedUpaithric class will be called before the +load method of the __ARCLite__ class, as ListedUpaithric is enlisted as the first non-lazy class.

It’s worth noting that the +load method of the __ARCLite__ class contains no valid code. The reason is because it is located within the __text section of the executable, which is encrypted.

The +load method of the ListedUpaithric class is physically located in a section of the executable that has a random name, such as __amorpha or __mottled.

Once run, the +load method will take a 32-byte XOR key that is hard-coded in the body and use that key to decrypt the __text section (around 15KB in size) of the executable, including the +load method of the __ARCLite__ class.

The decryption routine relies on a special anchor stored in the __text section. The virtual address of this anchor is used to describe the virtual address and virtual size of the encrypted __text section.

For example, the anchor can be located at the virtual address 0x100001CF0, as shown below:

__text:000100001CF0 23 anchor db 23h ; # ; DATA XREF: decrypt_code+101

__text:000100001CF1 2B db 2Bh ; +

...

In that case, the decryptor uses the address of the anchor to describe the parameters of the __text section. In the snippet below, the decryptor makes the __text section writeable and executable, by assigning a new protection to it. To do that, it takes the address of the anchor (0x100001CF0) and subtracts 0xBA0 from it to locate the start of the __text section (0x100001150):

vm_protect(mach_task_self(), // decoded stings: 'vm_protect', 'mach_task_self_'

(char *)&anchor – 0xBA0, // 0x100001150 –> start of the __text section

0x37F2, // size of the entire __text section: 14,322 bytes

0,

VM_PROT_ALL) // assign read, write, and execute access rights

Once the entire __text section is decrypted, the anchor shown above gets decrypted into the following text:

__text:000100001CF0 MaximMaximovicIsayev db 'Maxim Maximovich Isayev',0

Being next in line, the +load method of the __ARCLite__ non-lazy class is called to perform further initialization.

The decrypted __text section is quite small – it’s a valid code section containing a valid entry point, and it consists of another layer of decryptor and decompressor:

__text:0000000100001150 public start

__text:0000000100001150 start proc near

__text:0000000100001150 push 0

__text:0000000100001152 mov rbp, rsp

__text:0000000100001155 and rsp, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h

__text:0000000100001159 mov rdi, [rbp+8]

With both non-lazy classes realized, the entry point above receives control. From there, the main() function of the executable is called, followed by _exit().

Once decrypted, the anchor point within the encrypted __text section represents itself as a hidden text that is quite interesting by itself.

The following are some facts about Maxim Maximovich Isayev.

|

Maxim Maximovich Isayev (Максим Максимович Исаев) is the real name of Max Otto von Stierlitz, the lead character [4] in a popular Russian book series written in the 1960s. A Soviet James Bond [5], Stierlitz takes a key role in SS Reich Main Security Office in Berlin during World War II. Working as a deep undercover agent within the SS, he diverts the German nuclear ‘Vengeance Weapon’ research program into a fruitless dead-end. |

Leaving a hidden marker like this could indicate an intentionally planted false flag. Regardless of the intention, this maker stays constant across the entire family of this bundleware.

Once the entry point within the __text section is called, the main() function that follows it will read an internal chunk of data with a size of ~300KB.

This encrypted data is stored in a separate section of the executable.

The data will be read, its CRC32-based hash validated, then decrypted and further decompressed into a buffer, allocated with the vm_allocate() function.

The decompression is achieved by dynamically loading the libz.1.dylib library, and calling the uncompress() API from it.

The decompressed data has a size of ~800KB and Mach-O executable format (MH_BUNDLE type). This data is loaded from memory as a plug-in with the help of the NSCreateObjectFileImageFromMemory() and NSLinkModule() APIs.

This method is equivalent to dynamic DLL loading on Windows. It is described on the macOS man page [6] as a way to programmatically load plug-ins [7] after a program starts executing.

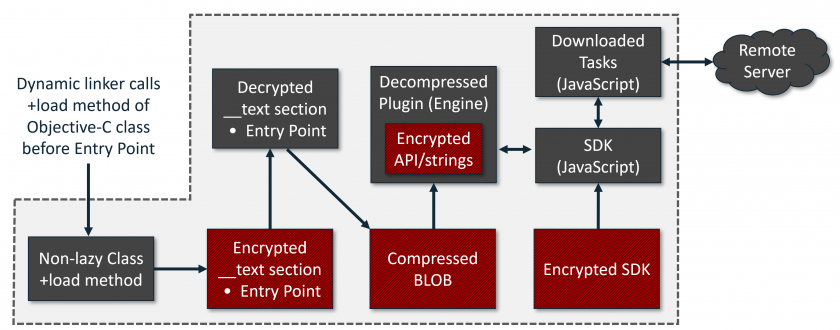

The loaded module represents itself as an engine driven by the JavaScript files.

Some of the scripts reside in the app’s Resources directory in an encrypted form, forming an SDK. Other JavaScript files are fetched from a remote server as tasks (internally called ‘offers’, as they are designed to offer/advertise other products).

Figure 1: Engine driven by JavaScript files.

Figure 1: Engine driven by JavaScript files.

The downloaded tasks rely on high-level function calls from the SDK. This allows the composing of tasks with a very flexible logic.

There are several classes exposed by the engine to the SDK, such as:

The engine itself is executed on the macOS platform natively.

For example, a JavaScript task may attempt to elevate the privilege level with the following call:

function relaunchWithRoot() {

installer.relaunchingWithRoot = true;

var successR = installer.elevatePrivilegedTask();

The elevatePrivilegedTask() call in JavaScript has a corresponding method in the engine’s class, such as tr54jds23. The engine exposes this method to JavaScript code so that it can be called directly from the engine.

When tr54jds23->elevatePrivilegedTask() is executed, the engine calls another method: ICTaskManager->elevatePrivilegedTask().

That will, in turn, create the task ICTaskManager->root_Task, which will then create an authorization with the 'system.privilege.admin' flag. Next, the task is executed with the AuthorizationExecuteWithPrivileges() call.

In practice, this may invoke a dialog asking for the admin password so that the task can be executed as root.

The engine module stores the names of all critical functions and most critical strings encoded. In one of the most recent samples, there are 1,228 encoded strings, decoded with 1,055 different functions. That is, some strings are decoded with the same function.

All the string-decoding functions use different keys, but they implement one of the following three algorithms:

One of the string decryption routines can be demonstrated with the anti-debugging trick explained in the next section.

An attempt to attach to or run the bundleware app under a debugger produces the following error:

mac:/ user$ sudo lldb /Users/user/Installer/Installer.app

(lldb) target create "/Users/user/Installer/Installer.app"

Current executable set to '/Users/user/Installer/Installer.app' (x86_64).

(lldb) r

Process 1280 launched: '/Users/user/Installer/Installer.app/Contents/MacOS/radiosurgical' (x86_64)

Process 1280 exited with status = 45 (0x0000002d)

The anti-debugging defence is provided with a ptrace() request named PT_DENY_ATTACH (0x1F), called from the function below:

ptrace = 0x515D5A5D; // encrypted 'ptrace' string: 5D 5A 5D 51

ptrace_plus_4 = 0x5752; // 52 57

ptrace_plus_6 = 0x33; // 33

ptrace[0] = add_2D_xor(0x5D, 0); // decrypt 1st char (5D ^ (2D + 0))

i = 1; // start loop from the 2nd char

do

{ // decrypt the rest

ptrace[i] = add_2D_xor(ptrace[i], i); // ptrace[i] ^= 2D + i

i++;

}

while (i != 6); // 6 characters from the 2nd char, including /0

fn_ptrace = dlsym(RTLD_NEXT, &ptrace); // get proc address from the dylibs

return fn_ptrace(PT_DENY_ATTACH, 0, 0, 0); // call ptrace(), deny tracing

If the process is being debugged, as defined in man ptrace [8], it will exit with the exit status of ENOTSUP (45), ‘error, not supported’. Otherwise, it sets a flag that denies future traces – an attempt to debug it with this flag set will result in a segmentation violation exception.

By stepping over the deny_attach() call (or NOP-ing the five bytes of the call), the anti-debugging trick above can easily be circumvented:

-> 0x103dd1ff5 <+25>: callq 0x103e30cd3 ; call the function with ptrace()

0x103dd1ffa <+30>: callq 0x103de03aa ; ICCrashLogger::sharedLogger()

0x103dd1fff <+35>: movq %rax, %rdi

(lldb) re w pc '$pc+5' ; step over deny_attach() by adding 5 bytes to $pc

(lldb) x/2i $pc ; now $pc (RIP) points to the next instruction

-> 0x103dd1ffa: e8 ab e3 00 00 callq 0x103de03aa ; ICCrashLogger::sharedLogger()

0x103dd1fff: 48 89 c7 movq %rax, %rdi

In April 2019, the string encryption algorithm was updated.

This time, each hard-coded integer number within a decryption function is encoded with a separate function.

| For example, number 6 is encoded as: | The same code is collapsed by Hex-Rays Decompiler into: |

| get_6 proc near push rbp mov rbp, rsp mov al, 3 ; al = 3 shl al, 2 ; al = 12 movsx ecx, al ; ecx = 12 mov eax, 65 ; eax = 65 xor edx, edx ; edx = 0 idiv ecx ; 65 / 12, eax = 5 mul cl ; eax = 60 mov cl, 65 ; cl = 65 sub cl, al ; cl = 65 - 60 = 5 inc cl ; cl = 6 movsx eax, cl ; result = 6 pop rbp retn get_6 endp |

signed __int64 get_6() { return 6; } |

The engine is able to detect the presence of a virtual environment through the method checkPossibleFraud(). This method is exposed to JavaScript, where it can be called as:

var isVm = system.checkPossibleFraud()>0 ? 1 : 0;

To achieve that, the engine compiles a so-called ‘fraud’ report that consists of the following details:

The crash logger sends a GET request to a remote script, disguised as a PNG file:

http[://]ec2-54-191-37-103.us-west-2.compute.amazonaws[.]com/black.png

The stats it submits to the remote script are encoded as URL parameters:

The installer uses two configuration files. The first one is dynamically extracted from an unused cavity of the installer’s own DMG file. This configuration is written into the DMG file (a process internally called ‘injection’) after the DMG file is built, and is encrypted with the AES-128 algorithm.

To locate the encrypted config within the DMG file, the installer module parses the contents of the file. For each pair of bytes, it subtracts one byte from another, until it locates the following signature that consists of seven 64-bit integers, such as:

__const:0000000103E51C40 signature dq 0Fh, 9, 3Eh, 23h, 7, 86h, 0Ch

Once located, the config is extracted and decrypted. As shown in the example below, the extracted configuration specifies the URL of an application to download and install:

PRODUCT_TITLE = Duolingo%202017

PRODUCT_DESCRIPTION = To%20install%20Duolingo%202017%20for%20Mac%20click%20Continue.

PRODUCT_VERSION = Mac

PRODUCT_PUBLIC_DATE = 2017

PRODUCT_FILE_NAME = Duolingo%20Setup%20

PRODUCT_FILE_SIZE = 260.8%20MB

CHNL = download7-Duolingo

DOWNLOAD_URL = http%3A%2F%2Fcdn.downloadfree2.com%2Fmacsoftware%2FBlueStacks-Installer.dmg

PRODUCT_LOGO_URL = http%3A%2F%2Fwww.download7.co%2Fgamegraphics%2F90.png

ROOT_IF_INSTALLED = com.bluestacks.BlueStacks

APP_NAME = BlueStacks

TOS_URL = http%3A%2F%2Fwww.download7.co%2Feula.html

TYP = http%3A%2F%2Fpiroga.space%2Fpages%2FDM%2FDMTYP.html%3Foffers%3D

EXIT_PAGE_URL = http%3A%2F%2Fpiroga.space%2Fpages%2FDM%2FDMInter.html

PRIVACY_URL = http%3A%2F%2Fwww.download7.co%2Fprivacy.html

ISPBROWSER = ch

%40REPORT_ADD_PARAMS = IRONBRO_ID%253D9309%2526INST_GUID%253D4136ef6c-c79c-49b3-9400-5f99e43ac3e0

INST_GUID = 4136ef6c-c79c-49b3-9400-5f99e43ac3e0

The second configuration file is provided as a JavaScript file, and is decrypted with the other SDK files from the app’s Resources directory.

This configuration defines multiple operational parameters, such as report and ad servers:

var appInfo = {

report: 'http://rp.[REMOVED].com',

ad_url: 'http://os.[REMOVED].com/MacDarwenDLM/?v=5.0',

requires_root: false,

root_if_installed: [''],

skip_vm_check: false,

...

The report server from the configuration is used to receive posted reports.

The example below demonstrates what data is posted to the report server:

AC = DarwenDLM

PrID = MacDarwenDLM

PrSub = MacDarwenDLM

RS = Q

IRVER = 106.1712

CHNL = download7-Duolingo

PROD_TITLE = Duolingo 2017

schemeName = MacDarwenDLM

OSName = OSX

OSVer = 10.12

OSLang = en

_makeDate = 201711091722

SDT = 20181004195204931

UID = 9C0C266E-266D-4D98-B83C-BCB2A3018EB7

BRW = Safari

OSPlat = 2

MAC_L = [REMOVED]000000000000%3A127.0.0.1%3A24%3A0

hddSize = 107374182400

_makerver = total20171107115116

Isuseradmin = 1

isVmDef = 1

inst_flv = no_injection_106.1712

dwa.SrcNo = 1

QuitPage = welcomePage

RepCnt = 1

ofrClPrm = 266E-266D-4D98-B83C-BCB2A3018EB7

As seen in the example, the data it posts contains basic system information, such as macOS version number (OSVer), language (OSLang), MAC and IP addresses for all network interfaces (MAC_L), default browser name (BRW), HDD size, whether a VM was detected or not (isVmDef), whether the user is admin (isuseradmin), and some other parameters.

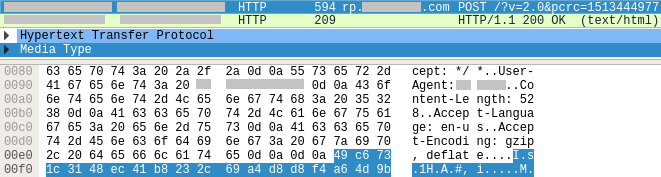

The collected data is assembled into a text, then encrypted with AES-128, and posted to the server:

Figure 2: The collected data.

Figure 2: The collected data.

Remote tasks are received encrypted from the ad server, as shown below:

POST os.[REMOVED].com/MacDarwenDLM/?v=5.0

USER-AGENT: ICMAC

Response:

Header: X-ICSCT-SERVER-NAME: ads-slave-1111-production-us-west-2-i-07e9c6437616f3e49

Data: 85,368 bytes binary [6c ec 6c 99...]

When the received task is decrypted, its data is split into named sections. Each section is surrounded with the following comments:

var namestartstr = '<!--SECTION NAME="';

var nameendstr = '"-->';

var sectionendstr = '<!--/SECTION-->';

The parser extracts JavaScript code from those sections. That code will then rely on APIs exposed by the SDK to drive the engine that exposes its own API interface to the SDK.

The nature of the received tasks may depend on the presence of a VM (a condition internally called ‘fraud’).

An analysis of the tasks received from the ad server reveals no malicious activity.

The bundleware’s engine consists of several components, capable of doing the following:

Being a legitimate distribution platform, the techniques employed by this popular bundleware product conceal a very powerful engine.

When viewed from a certain angle, this engine resembles a backdoor as it unlocks full access to the system.

The sheer power of the engine is made covert with the wisely engineered trickery. Some of its methods, such as loading code from memory, are known from the The Mac Hacker’s Handbook [9], and rather belong to the world of malware.

Given that the engine is driven by symmetrically encrypted remote tasks, any researcher who pays attention to detail couldn’t help but wonder what would happen if the control of its engine were to be intercepted.

Careful analysis of these techniques also demonstrates a disturbing trend we’re witnessing – the continued ‘spill’ of the traditional Windows malicious techniques, such as run-time packing, strings/API obfuscation and memory injection into the Mac world.

Even though the installer itself is legitimate, an analysis of state-of-art code where these techniques are honed to perfection is vitally important for researchers to understand what opportunities exist on the macOS platform, to be better prepared for the challenges that lie ahead of us.

[1] AppKit. https://developer.apple.com/documentation/appkit.

[2] objc-runtime-new.mm. https://opensource.apple.com/source/objc4/objc4-532/runtime/objc-runtime-new.mm.

[3] objc-file.mm. https://github.com/opensource-apple/objc4/blob/master/runtime/objc-file.mm.

[4] Stierlitz. Wikepedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stierlitz.

[5] Was the Soviet James Bond Vladimir Putin’s role model? BBC. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-39862225.

[6] NSModule – programmatic interface for working with modules and symbols. http://mirror.informatimago.com/next/developer.apple.com/documentation/Darwin/Reference/ManPages/man3/NSModule.3.html.

[7] NSObjectFileImage – programmatic interface for working with Mach-O files. http://mirror.informatimago.com/next/developer.apple.com/documentation/Darwin/Reference/ManPages/man3/NSObjectFileImage.3.html.

[8] Ptrace – process tracing and debugging. http://mirror.informatimago.com/next/developer.apple.com/documentation/Darwin/Reference/ManPages/man2/ptrace.2.html.

[9] Miller, C. The Mac Hacker’s Handbook. https://www.amazon.com/Mac-Hackers-Handbook-Charlie-Miller/dp/0470395362.