Check Point, Israel

In a fundamental regime that is constantly wary of anything that might jeopardize its stability, and a region that is a hotbed of political conflicts and dissensions, it is not surprising to discover a large‑scale surveillance campaign that keeps an eye out not only for external threats, but also for internal ones.

Lately, we uncovered an operation dubbed ‘Domestic Kitten’, which uses malicious Android applications to steal sensitive personal information from its victims: screenshots, messages, call logs, surrounding voice recordings and more. This operation managed to remain under the radar for a long time, as the associated files were not attributed to a known malware family and were only detected by a handful of security vendors.

Whether it is an application that changes the device’s background into ISIS-related images, or one that impersonates a legitimate Kurdish news agency, the malicious APKs used by this actor were tailored for the use of specific ethnic groups. Those ethnic groups and minorities can be considered a natural enemy to the Islamic Republic of Iran: Kurds, ISIS supporters, Sunni Muslims, and even Iranian citizens.

Our suspicions of the attack’s origin were confirmed when we were able to gain access to logs that were uploaded from the victims’ infected devices to the C&C servers. The information we gathered from those findings revealed the true dimensions of the attack as well as its lifespan, with the earliest malicious instances dating back to 2016.

In our presentation, we will discuss the evolution of the mobile spyware, the Iranian fingerprints it carries, and the political motives behind the launch of such an attack. In addition, we will share never-before-seen insights into the data stolen from hundreds of victims.

Domestic Kitten is a targeted attack and a surveillance operation that has been utilizing backdoors for Android devices to infect victims in the Middle East since at least 2016.

We assess with high confidence that this attack originates from the Islamic Republic of Iran and, surprisingly enough, although it has managed to infect hundreds in multiple countries in the Middle East, the majority of its victims are Iranian. This led us to believe that this is an internal Iranian operation, and earned the attack its name: Domestic Kitten.

Our investigation started when we found one instance of the mobile backdoor that targeted ISIS supporters, and through it we were able to track a large-scale campaign that has remained under the radar for years, and is still active even after we uncovered and publicly disclosed most of its TTPs.

The first malicious APK we found was one that masqueraded as an application for changing wallpapers. The application was called ‘The State of the Islamic Caliphate’ (translated from Arabic), and offered ISIS-themed wallpapers.

Figure 1: The first malicious APK masqueraded as an application offering ISIS-themed wallpapers.

The Manifest file revealed that the application has permissions to access almost everything stored on the device it is installed on, including logged-in accounts, call history, contacts, and more.

Figure 2: The application has permissions to access almost everything stored on the device.

The MainActivity is found in the ‘intense.pub1.sbgs’ package, which is in charge of the wallpaper changing functionality.

Figure 3: The MainActivity is found in the ‘intense.pub1.sbgs’ package.

Another interesting package that caught our attention was ‘com.andriod.browser’, as a class in this package is called from the MainActivity. Not only does this package misspell the word ‘android’, but it is also the malicious component of this app.

Figure 4: The ‘com.andriod.browser’ package.

The ‘com.andriod.browser’ functionality is straightforward and the code is not heavily obfuscated.

Figure 5: com.andriod.browser.

The server address that the application communicates with can be found in the ‘Settings’ class, along with a code name for the application, ‘daeshsh’, which is the Arabic or Persian name for ISIS (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: The settings class contains the server address for communication as well as a codename for the application, ‘daeshsh’.

The ‘CommandManager’ class receives commands from the C&C by regularly sending the deviceUUID (a unique identifier for each victim) as a parameter to the ‘get-function.php’ script, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: deviceUUID is sent as a parameter to the ‘get-function.php’ script.

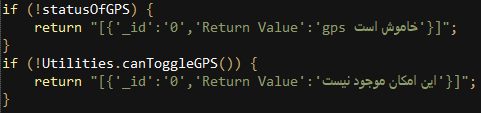

There are six types of commands that the C&C server can respond with: Get, Set, Take, Reset, Time and Delete. These commands enable the application to collection information about the device (including its model and location), steal any file on the system, delete messages or calls, take photos or videos, and even build structured logs from the device’s data.

Figure 8: The six types of commands the C&C server can respond with.

Each command is separated from its parameters by the ‘~~~’ delimiter, and different commands are separated by the ‘===’ delimiter (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Each command is separated from its parameters by the ‘~~~’ delimiter, and different commands are separated by the ‘===’ delimiter.

The structured logs can include all of the victim’s call history, browsing history, SMS messages, and more. Each log contains one type of data only, and starts with a different character that indicates what its content is. For example, the log containing SMS messages starts with the character ‘Z’. The fields stored in the logs are separated by the same unique delimiter as the commands: ‘~~~’.

Figure 10: The log containing SMS messages starts with the character ‘Z’.

We were able to hunt for more samples using code similarity, shared infrastructure, names of malicious packages, and a unique email address which appeared in the APK’s certificate.

Figure 11: APK certificate showing unique email address.

As a result, we found hundreds of backdoored applications belonging to this attack and using different themes to lure victims into downloading them.

Figure 12: Different themes were used to lure victims into downloading the backdoored applications.

There were multiple variants of the backdoors that were used over the years by the attackers. We will differentiate between the generations using the name of the malicious package in each variant:

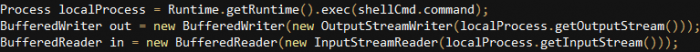

This is the oldest variant we were able to relate to this activity – it dates back to 2016. In addition to the data theft capabilities (device location, phone call recordings, etc.), it is capable of executing remote shell commands.

Figure 13: Com.memopt is capable of executing remote shell commands.

Surprisingly, some of the exception messages in this variant are documented in Persian:

Figure 14: Exception messages documented in Persian.

This variant is slightly more advanced than the previous ones and was introduced towards the end of 2018. The malicious package name was changed to ‘com.golf.rv’ or ‘com.internalcopy.c204’ in newer backdoors we discovered during 2019, which still maintain the same functionality and capabilities.

The code in these variants is obfuscated and protective layers are added to prevent any detection of strings. All strings, including the server, are encoded using a simple algorithm, which adds a constant to each character of the string and encodes the result using Base64.

Figure 15: A simple algorithm adds a constant to each character of the string and encodes the result using Base64.

This variant appears to be used for testing purposes by the attackers, as the malicious package was found in applications that were called ‘New 2019.apk’ (although it dates back to 2017). In multiple instances in this package, the attackers referred to the backdoor as ‘Kosar’, which might mean that this is the internal name they use for the malicious applications.

Figure 16: ‘Kosar’ might be the internal name the attackers use for the malicious applications.

The initial infection vector of this attack is still unknown, but we believe that the attackers use services such as Telegram to reach potential victims.

One of the malicious applications we came across was downloaded from ydownyload[.]net. Not much information could be found online about this domain, but it hosted a ‘download center’ from which close to 100 malicious backdoors belonging to this campaign could be downloaded.

Figure 17: Download center.

Among the downloaded backdoors were new and previously unseen variants that were introduced during 2019, as well as new C&C servers that they communicated with.

Therefore, it is possible that the victims are sent URLs via phishing messages to download the backdoors directly from this website.

Examining the names of the malicious applications can reveal who they might be targeting, since the majority of them have names in Arabic, Persian or Kurdish. In addition, the content they offer is usually appealing to certain ethnic or religious groups in the Middle East. Many of the applications have political or religious themes, with names such as ‘Verses from the Quraan’, ‘Kurdish Poetry’, or ‘Tehran Military News’. There are also some with names in English that serve generic use cases and may target a broader audience or entities (such as ‘Google Service Updater’, ‘Super VPN’, ‘Telegram X’, and so on).

Findings from the threat actors’ servers confirmed our suspicion, and showed that this attack focuses on targets in the Middle East, specifically countries such as: Iran, Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

Figure 18: The attack focuses on targets in the Middle East.

The different religious sects in those countries, and their struggle for power, often lead to internal conflicts and civil wars, with the most recent example being the ongoing civil war in Yemen between the Houthis and the Yemeni government. This civil war reflects the broader and deeper conflict between the Sunni and the Shia Muslims in the region, which was also viewed as the root cause for similar disputes in Iraq and Syria.

It appears that the attackers behind Domestic Kitten might be affiliated with one of the conflicting sides, which would explain the geopolitical motivations behind monitoring the mobile devices belonging to members of certain groups or minorities within those countries. This would also explain why the attackers were after some of the high-profile targets we discovered among the victims during our investigation, and how they would be of interest to a surveillance operation that watches out for any dissidents or potential threats.

WHOIS information behind some of the involved domains showed that they were supposedly registered by Iranian individuals. In addition, some of the related IP addresses were located in Iran, or had numerous Iranian top-level domains resolving to them. This is supported further by the Persian words and comments that were seen in some of the backdoors.

Figure 19: WHOIS information.

Although these may be false flags left by the attackers, the victims and the geopolitical motivations behind this operation do align with the political targets of Iran in the region.

Domestic Kitten managed to remain under the radar for a long period, dating back to at least 2016. Its ability to stay under the radar might be due to the fact that this is a dynamic operation: its infrastructure constantly changes, it introduces new capabilities and changes its code and package names.

Domestic Kitten is yet another example of how an attack that is not highly advanced in terms of the deployed tools still manages to make its way to more and more victims each day, and to get its hands on highly sensitive information by infiltrating mobile devices belonging to government officials in the Middle East.