Check Point, Israel

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

Malicious Android applications are quite common, and can even be found from time to time in the Google Play Store. Thus, a lot of work has been done in both industry and academia on Android app analysis, and in particular, static code analysis.

One of the problems faced by static code analysis is encryption of sensitive strings, e.g. names of functions called by reflection. App developers can perform such encryption by writing custom code, or using off-the-shelf obfuscators.

Dynamic code analysis – running the app in an emulator – is not affected by such obfuscation techniques, because the sensitive data is decrypted by the app's code at runtime. To leverage this advantage, we created a combined analysis process, composed of both dynamic and static analysis modules, in which the dynamic module extracts the decrypted data and passes it to the static module.

One challenge immediately comes to mind: while static analysis can analyse every line of code in the app, dynamic analysis is only aware of the code that actually runs. In other words, we might have to work hard during dynamic analysis to reach all possible flows where encrypted data is used. The solution is to make the dynamic module more active by showing it the right direction. The static module searches the app code for all invocations of the decryption code, which is usually in the form of a static function (e.g. in off-the-shelf obfuscators such as DashO, KlassMaster and others). It provides the dynamic module with a list of function calls, including argument values. The dynamic module performs these function calls and returns the results to the static module, which then patches the app code using the decrypted strings.

We implemented this concept and tested it on samples obfuscated by DashO. As we hoped, this approach enabled static analysis to detect new suspicious behaviours in applications with previously limited analysis coverage.

As of May 2018, Android is the most popular commercial operating system in the world (definitely the most popular mobile OS; prevalence over Windows is within statistical error [1]), with millions of applications available for download from numerous global application markets [2]. The prevalence of the OS, its open ecosystem and well established global app distribution model contribute to the creation of a dangerous attack surface that is exploited by numerous threat actors ranging from opportunistic 'script kiddies' looking for fame and glory, via criminal organizations hacking for profit, to government agencies on spying missions.

In spite of genuine efforts by the operators of the app markets, malware does manage to find its way inside, sometimes reaching millions of downloads before being removed. Malware apps sometimes even manage to sneak into Google Play, the largest and the most well protected of the Android app markets [3]. Alternative app stores are often even less well protected.

As a result, a lot of effort has been invested, both in the industry and academia, into developing methods of automatic Android app analysis that could quickly and accurately separate malicious apps from benign ones.

One of the widely used methods, often called 'dynamic analysis', involves running the application in a controlled environment: a sandbox, an emulator or a quarantined physical device. During runtime, the analysis code monitors the state of the application and the operating system. If the app accesses sensitive user information, tries to exploit a known vulnerability, communicates with its C&C server or exhibits other suspicious behaviour, it will be discovered by the analysis code. And since the malicious code is contained inside the sandbox, no actual harm can be done.

Although dynamic analysis can be very effective, it also has shortcomings – its coverage of the app's behaviour can be limited as it can only analyse behaviours actually happening during the analysis time. Malicious behaviours that are triggered by input from the user, network events and temporal events could be completely invisible to the dynamic analysis. Some malicious applications take advantage of this weakness by intentionally employing various evasion or anti-emulation techniques, for example by implementing a 'time bomb', which is a mechanism that defers the execution of a malicious behaviour until some time later in the future, hopefully beyond the scope of the ongoing analysis.

A completely different approach to code analysis, which is also very common, is known as 'static code analysis', 'data-flow analysis' or 'taint analysis' [4]. In this method, the analysis tries to gain insights about the code's functionality without running it. In particular, it analyses the flow of data within the code, in order to find out how sensitive user data is handled. For example, the analysis can look for all function calls that result in opening a network socket, and then follow the variable that references the socket, to find out if any sensitive user data is written to the socket.

Static analysis can sometimes cover behaviour that isn't covered by dynamic analysis. For example, if the code that performs this behaviour is protected by a time bomb or another evasion technique.

One of the obstacles that static analysis faces when analysing real-world applications is code obfuscation. Code obfuscation is used by legitimate app developers to protect their intellectual property, but also by malicious apps to evade detection. Some developers may choose to implement their own methods of obfuscation, but most use off-the-shelf obfuscation solutions.

Unlike static analysis, dynamic analysis isn't hindered by obfuscation. The functionality of the obfuscated code during runtime is equivalent to the functionality of the original code, regardless of whether it runs in a sandbox/virtual device or on a real Android device. For example, sensitive strings encrypted during obfuscation are decrypted at runtime. This means dynamic analysis can reveal information that is potentially beneficial to static analysis, and could enable it to improve its coverage of obfuscated code.

In our research, we chose to tackle two related obfuscation techniques: string encryption and dynamic method binding via reflection. The second technique is often combined with the first one. That is, the strings containing the names of the classes and methods called by reflection are also encrypted.

We considered multiple approaches. For example, we considered making the dynamic analysis module intercept the decrypted strings when they are returned from the decryption code by placing breakpoints. Unfortunately, full code coverage is the Achilles' heel of dynamic analysis. Therefore, this approach doesn't guarantee decryption of all the needed data – the dynamic analysis might just not reach it in its usual flow.

To maximize coverage, we implemented a more sophisticated approach. Instead of passively waiting for the string to be decrypted, the dynamic analysis can actively execute the decryption code. Of course, cherry-picking the interesting calls could be very complicated, especially if the call depends on the context or some previously calculated state. Fortunately, many common obfuscators use static, stateless code to perform the decryption. For the first stage of our research we limited ourselves to such obfuscators, as we'll show in the following sections.

Common obfuscation techniques include, among others:

Class and method renaming seems to be the most common technique in malicious apps and apps found in third-party markets [5], so it might seem like a natural choice for deobfuscation research. However, since the original names are completely removed from the app installation file, deobfuscation is simply not possible. Fortunately, renaming only poses a problem to 'manual' reverse engineering, because automated static analysis doesn't rely on the meaning of the names found in the code (except for names from the Android API or Java library, but these cannot be modified). Therefore, we chose to focus on string encryption and reflection. They are both quite common, and dealing with the first one allows us to deal also with the second.

Although previous work has already been done to assess the prevalence of different obfuscators in the Google Play Store [6], we wanted to gather such statistics on a larger scale. Also, many of the obfuscators that support string encryption allow the user to choose whether to use it or not, since it can impact performance [7, 8]. Therefore it was important to find out specifically how common are different implementations of string encryption, by different off-the-shelf obfuscators.

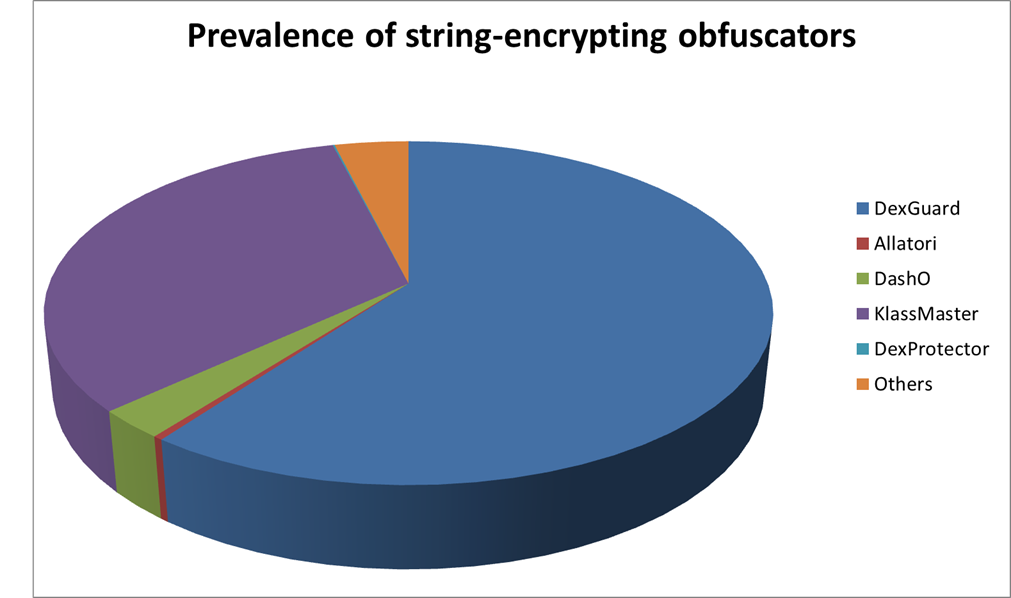

We ran statistics on 400,000 malicious APKs and 6 million non-malicious Android apps from Check Point's app repository. Using code signatures for different implementations of string decryption, we identified whether an app is obfuscated by one of the common obfuscators known to us (refer to the 'Experiments and results' section for an example of such a signature). We found that 3.6% of the apps were obfuscated using string encryption. It's interesting to note that string encryption isn't more common among malicious apps. In fact, only 3.5% of the malicious apps we examined contained encrypted strings. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of the data.

| Obfuscator | Out of obfuscated apps | Out of all apps |

| Allatori | 0.37% | 0.01% |

| DashO | 2.71% | 0.10% |

| DexGuard | 60.2% | 2.17% |

| DexProtector | 0.1% | <0.01% |

| KlassMaster | 32.93% | 1.18% |

| Other | 3.87% | 0.14% |

Figure 1: Prevalence of string-encrypting obfuscators.

The typical obfuscator implements string encryption in the following manner. During build time:

During runtime, the decryption code for any particular string runs immediately before the app code reads that string.

As an example of a relatively simple method of string encryption, we chose DashO, a commercial obfuscator developed by PreEmptive Solutions [9].

DashO replaces occurrences of sensitive strings with function calls to a static decryption function. The arguments passed to the function include a string and a number. Both arguments are constants, whose initialization is adjacent to the decryption function call. An example can be seen in Excerpt 1, which is from a malicious app called com.software.app [10], disassembled into smali code [11].

const-string v1, "\t\u001b\u0002\u0019\u0019\u0001\u0014EX"

const/16 v2, 0x79

invoke-static {v1, v2}, Lcom/software/app/Activator$2;->getChars(Ljava/lang/String;I)Ljava/lang/String;

move-result-object v1

The same decryption function, Activator$2;->getChars, is called many times throughout the application code, each time with different arguments. The decryption logic is contained entirely inside the decryption function, and doesn't use additional data apart from the arguments passed to the function. The code (from the same malicious app) can be seen in Excerpt 3, in the Appendix.

DexGuard is a commercial obfuscator developed by GuardSquare [12] (who also develop ProGuard, a popular open-source obfuscation and optimization tool). Its implementation of string encryption is more complex than the previous example.

DexGuard replaces string occurrences with calls to a static decryption function, as in the previous example. But it doesn't use the same function for all decryption instances. Instead, variations of the function are generated for each of the classes where string encryption is used. These variations differ both in the constants they contain as well as in the opcodes.

Also, the decryption logic isn't at all contained within the decryption function. Some of it is actually inserted into the function where the original string instance appears, as can be observed in Excerpt 2, which is from a malicious app called com.xomyjmqmlapu.pahrxyxea [13]. In addition, a static binary array containing encrypted data is generated in each class where string encryption is enabled. This array is accessed by the decryption function, and also by the function that calls it. The result is that discovering the value of the arguments passed to the decryption function isn't as trivial as in the case of DashO.

sget-object v2, Lcom/ipduqdlyvx/dakgeycodriu/s;->aa:[B

const/16 v3, 0x65

aget-byte v2, v2, v3

neg-int v2, v2

sget-object v3, Lcom/ipduqdlyvx/dakgeycodriu/s;->aa:[B

const/16 v4, 0x19f

aget-byte v3, v3, v4

neg-int v3, v3

const/16 v4, 0xde

invoke-static {v2, v4, v3}, Lcom/ipduqdlyvx/dakgeycodriu/s;->Q(III)Ljava/lang/String;

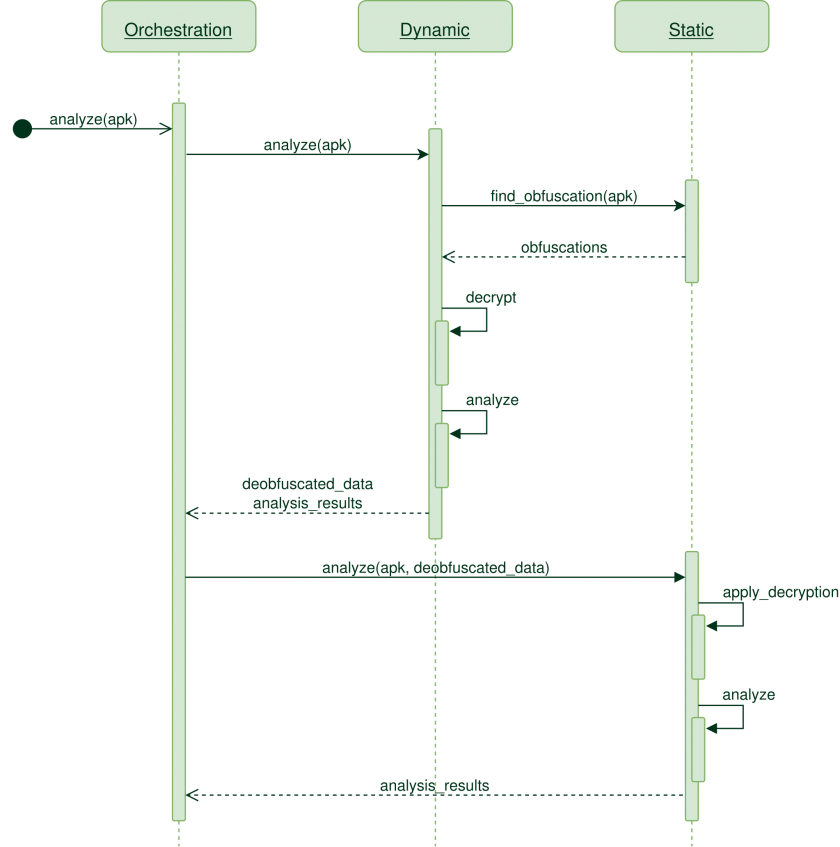

The deobfuscation flow is illustrated in Figure 2. The steps are as follows:

Figure 2: Deobfuscation flow.

Figure 2: Deobfuscation flow.

Our experiments employed the existing application analysis infrastructures in Check Point. The central elements we used were:

The first step of our research was to collect the data. Although we had a huge set of applications, they were not properly tagged with the obfuscation information. We used the following signature to locate the required obfuscated apps for further analysis:

Signature for DashO decryption function

Once the samples were tagged, we could finally run our algorithm and validate the thesis.

Since DashO's implementation of string encryption is relatively simple, we chose it for the first experiment.

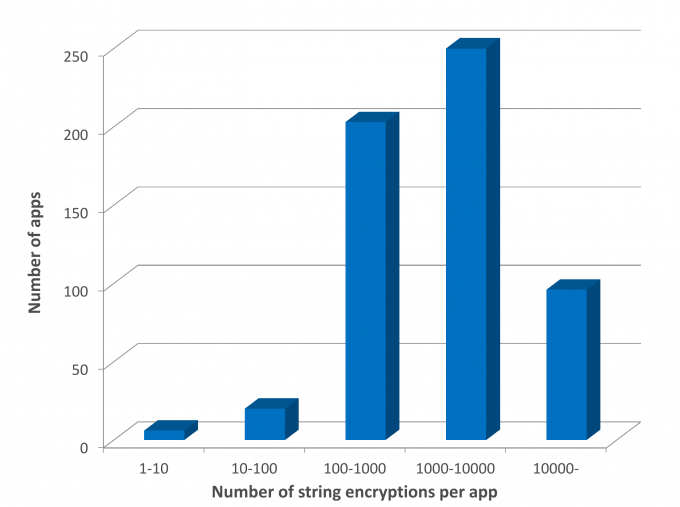

We created a data set composed of 586 samples, each of them an Android application, either malicious or benign, containing strings encrypted by DashO.

We ran all the apps in our dynamic analysis infrastructure, which first used the static analysis infrastructure to identify all decryption calls and extract argument values. After the first static analysis phase, the dynamic analysis executed all the decryption calls. The decryption results were saved to JSON files that were passed to the static analysis infrastructure in order to perform full static analysis of each sample.

We also ran the static analysis infrastructure on the same samples without feeding it with any decrypted string data.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the number of encrypted strings among the different apps we tested. Recall that obfuscators such as DashO allow the user to encrypt just some of the strings in the code, to reduce the performance hit caused by having to run the decryption code during the application runtime.

Since we have no ground truth for these samples, we cannot estimate the recall of the decryption call identification. But we do know that argument values were successfully retrieved for 99% of the decryption calls, on average.

In 61 out of 586 samples (10.4%), static analysis detected new data flows that it had not detected without the string decryption. Some of these flows involved:

Figure 3: Encryptions per app.

Figure 3: Encryptions per app.

We implemented the complete deobfuscation solution and tested it on hundreds of Android applications. The experiment confirmed our assumptions and enabled detection of new behaviours in applications with previously limited analysis coverage. More importantly, the research demonstrates that modern threats require holistic approaches to application analysis. It is not enough to choose one approach – effective threat prevention requires collaboration of multi-disciplinary teams employing a wide range of techniques.

Possible directions for further research include:

Finally, since obfuscation is often used to protect intellectual property in benign apps, rather than to conceal malicious behaviour, it is worth mentioning that implementing a deobfuscation system as we described here is far from trivial. This research is aimed at developers of automated malware detection solutions, rather than for researchers interested in reverse-engineering particular obfuscated Android apps for their intellectual property.

[1] http://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share.

[2] https://www.statista.com/statistics/266210/number-of-available-applications-in-the-google-play-store/.

[3] https://source.android.com/security/reports/Google_Android_Security_2017_Report_Final.pdf.

[4] https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/20223/1/far%2B14flowdroid.pdf.

[5] Understanding Android Obfuscation Techniques: A Large-Scale Investigation in the Wild. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1801.01633.pdf.

[6] Who Changed You? Obfuscator Identification for Android. http://web.cse.ohio-state.edu/presto/pubs/msoft17.pdf.

[7] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-65687-8_21.

[8] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404817302092.

[9] https://www.preemptive.com/products/dasho/overview.

[10] https://www.virustotal.com/#/file/833ac61ca31366995f9b3ad4f77a838d44fac0317ecfd5bc31f1adeb149c3543/detection.

[11] https://github.com/JesusFreke/smali/wiki.

[12] https://www.guardsquare.com/en/dexguard.

[13] https://www.virustotal.com/#/file/d3ca9e40a2bd04896a0336ef2eb3dd6824786f2b7d040107cb7a5c39d945370f/detection.

[14] https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2017/10/vb2017-paper-crypton-exposing-malwares-deepest-secrets/.

.method public static getChars(Ljava/lang/String;I)Ljava/lang/String;

.locals 5

const/4 v0, 0x0

:try_start_0

invoke-virtual {p0}, Ljava/lang/String;->toCharArray()[C

move-result-object v2

array-length v3, v2

:goto_0

if-eq v0, v3, :cond_0

aget-char v1, v2, v0

and-int/lit8 v4, p1, 0x5f

xor-int/2addr v4, v1

add-int/lit8 p1, p1, 0x1

add-int/lit8 v1, v0, 0x1

int-to-char v4, v4

aput-char v4, v2, v0

move v0, v1

goto :goto_0

:cond_0

const/4 v0, 0x0

invoke-static {v2, v0, v3}, Ljava/lang/String;->valueOf([CII)Ljava/lang/String;

move-result-object v0

invoke-virtual {v0}, Ljava/lang/String;->intern()Ljava/lang/String;

:try_end_0

.catch Lcom/software/app/Activator$ArrayOutOfBoundsException; {:try_start_0 .. :try_end_0} :catch_0

move-result-object v0

:goto_1

return-object v0

:catch_0

move-exception v0

const/4 v0, 0x0

goto :goto_1

.end method

.method private static Q(III)Ljava/lang/String;

.registers 9

add-int/lit8 p0, p0, 0x20

add-int/lit8 p1, p1, 0x4

new-instance v0, Ljava/lang/String;

const/4 v4, 0x0

sget-object v5, Lcom/ipduqdlyvx/dakgeycodriu/s;->aa:[B

rsub-int/lit8 p2, p2, 0x34

new-array v1, p2, [B

add-int/lit8 p2, p2, -0x1

if-nez v5, :cond_16

move v2, p0

move v3, p2

:goto_13

add-int/2addr v2, v3

add-int/lit8 p0, v2, -0x2

:cond_16

int-to-byte v2, p0

add-int/lit8 p1, p1, 0x1

aput-byte v2, v1, v4

if-ne v4, p2, :cond_26

const/4 v2, 0x0

invoke-direct {v0, v1, v2}, Ljava/lang/String;-><init>([BI)V

invoke-virtual {v0}, Ljava/lang/String;->intern()Ljava/lang/String;

move-result-object v0

return-object v0

:cond_26

move v2, p0

add-int/lit8 v4, v4, 0x1

aget-byte v3, v5, p1

goto :goto_13

.end method