Google, USA

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

Malware authors implement many different techniques to frustrate analysis and make reverse engineering malware more difficult. Many of these anti-analysis and anti-reverse engineering techniques attempt to send a reverse engineer down a different investigation path or require them to invest large amounts of time reversing simple code. This talk analyses one of the most interesting anti-analysis native libraries we've seen in the Android ecosystem. No previous references to this library have been found. We've named this anti-analysis library 'WeddingCake' because it has lots of layers.

This paper covers four techniques the malware authors used in the WeddingCake anti-analysis library to prevent reverse engineering. These include: manipulating the Java Native Interface, writing complex algorithms for simple functionality, encryption, and run-time environment checks. This paper discusses the steps and the process required to proceed through the anti-analysis traps and expose what the developers are trying to hide.

To protect their code, authors may implement obfuscation, encryption, and anti-analysis techniques. There are both legitimate and malicious reasons why developers may want to prevent analysis and reverse engineering of their code. Legitimate developers may want to protect their intellectual property, while malicious developers may want to prevent detection. This paper details an Android anti-analysis native library used by multiple malware families to prevent analysis and detection of their malicious behaviours. Some variants of the Chamois malware family [1] use this anti-analysis library, which has been seen in over 5,000 unique Android APKs. The APK with SHA256 hash e8e1bc048ef123a9757a9b27d1bf53c092352a26bdbf9fbdc10109415b5cadac is used as the sample for this paper.

The sample Android application includes a native library to hide the contents and functionality of native code. The Java Native Interface (JNI) allows developers to define Java native methods that run in other languages, such as C or C++, in the application. This allows bytecode and native code to interface with each other. In Android, the Native Development Kit (NDK) is a toolset that permits developers to write C and C++ code for their Android apps [2]. Using the NDK, Android developers can include native shared libraries in their Android applications. These native shared libraries are .so files, a shared object library in the ELF format. In this paper, the terms 'native library', 'ELF', and '.so file' are used interchangeably to refer to the anti-analysis library. The anti-analysis library that is detailed in this paper is one of these Android native shared libraries.

The bytecode in the .dex file of the Android application defines the native methods [3]. These native method definitions pair with a subroutine in the shared library. Before the native method can be run from the Java code, the Java code must call System.loadLibrary or System.load on the shared library (.so file). When the Java code calls one of the two load methods, the JNI_OnLoad() function is called from the shared library. The shared library needs to export the JNI_OnLoad() function.

In order to run a native method from Java, the native method must be 'registered', meaning that the JNI knows how to pair the Java method definition with the correct function in the native library. This can be done either by leveraging the RegisterNatives JNI function or through 'discovery' based on the function names and function signatures matching in both Java and the .so [4]. For either method, a string of the Java method name is required for the JNI to know which native function to call.

WeddingCake, the anti-analysis library discussed in this paper, is an Android native library, an ELF file, included in the APK. In the sample, the anti-analysis library is named lib/armeabi/libdxarq.so. The name of the anti-analysis library differs in each APK, as explained in the following section.

Within the classes.dex of the APK, there is a package of classes whose whole name is random characters. For the sample described in this paper, the class name is ses.fdkxxcr.udayjfrgxp.ojoyqmosj.xien.xmdowmbkdgfgk. This class declares three native methods: quaqrd, ixkjwu, and vxeg.

The native library discussed in this paper is usually named lib[3-8 random lowercase characters].so. However, we've encountered a few samples whose name does not match this convention. All APK samples that include WeddingCake use different random characters for their class and function names. It is likely that WeddingCake provides tooling that generates new random names each time it is compiled.

The most common version of the library is a 32-bit 'generic' ARM (armeabi) ELF, but I've also identified 32-bit ARMv7 (armeabi-v7a), ARM64 (arm64-v8a), and x86 (x86) versions of the library. All of the variants include the same functionality. If not otherwise specified, this paper focuses on the 32-bit 'generic' ARM implementation of WeddingCake because this is the most common variant.

As an example, the APK with SHA256 hash 92e80872cfd49f33c63993d52290afd2e87cbef5db4adff1bfa97297340f23e0, which is different from the one analysed in this paper, includes three variants of the anti-analysis library: generic ARM, ARMv7, and x86.

| Anti-analysis lib file paths | Anti-analysis library 'type' |

| lib/armeabi/librxovdx.so | 32-bit 'generic' ARM |

| lib/armeabi-v7a/librxovdx.so | 32-bit ARMv7 |

| lib/x86/libaojjp.so | x86 |

Table 1: Anti-analysis lib paths in 92e80872cfd49f33c63993d52290afd2e87cbef5db4adff1bfa97297340f23e0.

There are some signatures that help identify ELF files as a WeddingCake anti-analysis library:

- Android clang version 3.8.275480 (based on LLVM 3.8.275480)

- GCC: (GNU) 4.9.x 20150123 (prerelease)

Figure 1: JNI_OnLoad in IDAPro.

The JNI_OnLoad function is the starting point for analysis because there are no references to the native methods that were defined in the APK. For this sample, the following three methods were defined as native methods in ses.fdkxxcr.udayjfrgxp.ojoyqmosj.xien.xmdowmbkdgfgk:

public static native String quaqrd(int p0);

public native Object ixkjwu(Object[] p0);

public native int vxeg(Object[] p0);

There are no instances of these strings existing in the native library being analysed. As described in the 'Introduction to JNI' section, in order to call a native function from the Java code in the APK, the ELF must know how to match a Java method (as listed previously) to the native function in the ELF file. This is done by registering the native function using RegisterNatives() and the JNINativeMethod struct [5]. We would normally expect to see the Java native method name and its associated function signature ([Ljava/lang/Object;)I) as strings in the ELF file. Since we do not, the ELF file is probably using an anti-analysis technique.

Because JNI_OnLoad must be executed prior to the application calling one of its defined native methods, I began analysis in the JNI_OnLoad function.

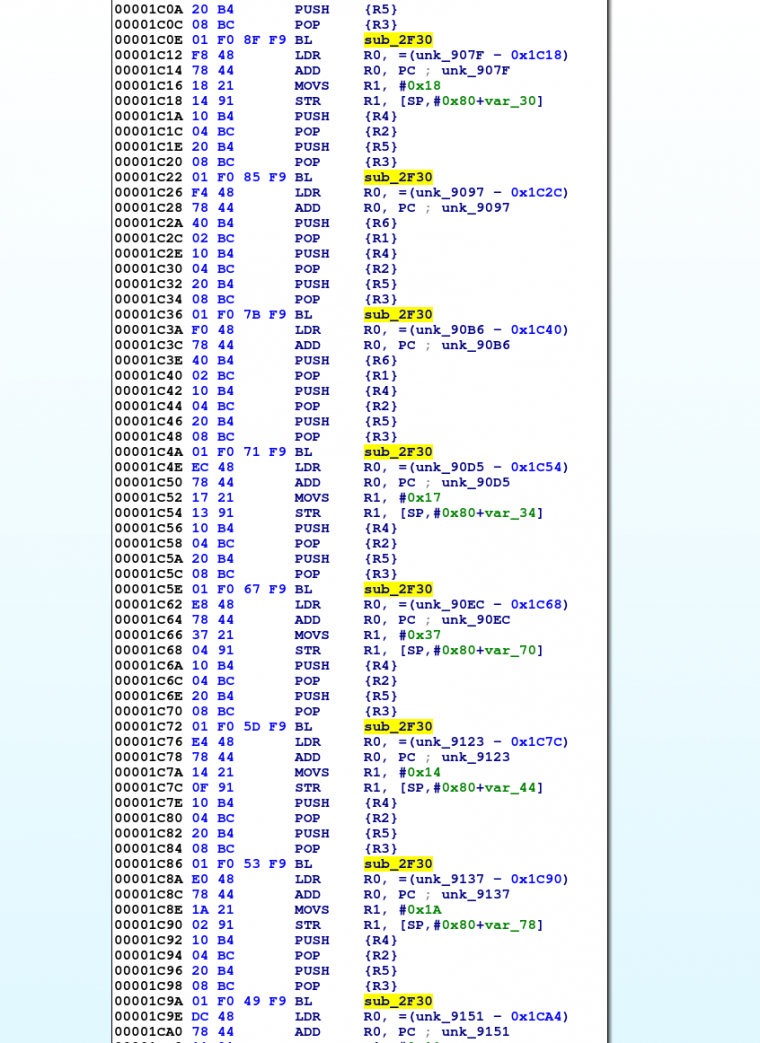

In the sample, the JNI_OnLoad() function ends with many calls to the same function. This is shown in Figure 2. Each call takes a different block of memory as its argument, which is often a signal of decryption. In this sample, the subroutine at 0x2F30 (sub_2F30) is the in-place decryption function.

Figure 2: Calls to the decryption subroutine in JNI_OnLoad in IDA Pro.

Figure 2: Calls to the decryption subroutine in JNI_OnLoad in IDA Pro.

To obscure its functionality, this library's contents are decrypted dynamically when the library is loaded. The decryption algorithm used in this library was not matched to a known encryption/decryption algorithm. The decryption function, found at sub_2F30 in this sample, takes the following arguments:

sub_2F30(Byte[] encrypted_array, int length, Word[] word_seed_array, Byte[] byte_seed_array)

The decryption function takes two seed arrays as arguments each time it is called: the word seed array and the byte seed array. These two arrays are generated once, beginning at 0x1B58 in this sample, prior to the first call to the decryption function. The byte array is created first; in this sample, it's generated at 0x1B58. The word array is created immediately after the byte array initialization at 0x1BD0. The word seed array and byte seed array are the same for every call to the decryption function within the ELF and are never modified.

The author of this code obfuscated the generation of the seed arrays. The IDA decompiled code for the generation of the two arrays, byte_seed_array and word_seed_array, is shown in Listing 1.

byte_seed_array = malloc(0x100u);

index = 0;

do

{

byte_seed_array[index] = index;

++index;

}

while ( 256 != index );

v4 = 0x2C09;

curr_count = 256;

copy_byte_seed_array = byte_seed_array

do

{

v6 = 0x41C64E6D * v4 + 0x3039;

v7 = v6;

v8 = copy_byte_seed_array[v6];

v9 = 0x41C64E6D * (v6 & 0x7FFFFFFF) + 0x3039;

copy_byte_seed_array[v7] = copy_byte_seed_array[v9];

copy_byte_seed_array[v9] = v8;

--curr_count;

v4 = v9 & 0x7FFFFFFF;

}

while ( curr_count );

word_seed_array = malloc(0x400u);

index = 0;

do

{

word_seed_array[byte_seed_array[index]] = index;

++index;

}

while ( 256 != index );

Listing 1: The IDA decompiled code for the generation of the two arrays, byte_seed_array and word_seed_array.

These algorithms output the byte_seed_array and word_seed_array shown in Listing 2. The author of this code tried to frustrate the reverse engineering process of this library by writing complex algorithms which would require more investment of effort, time and skill to reverse engineer. Using a complex algorithm to accomplish a simple task is a common anti-reverse engineering technique.

byte_seed_array =

[0x0, 0x1, 0x2, 0x3, 0x4, 0x5, 0x6, 0x7, 0x8, 0x9, 0xa, 0xb, 0xc, 0xd, 0xe, 0xf, 0x10, 0x11, 0x12, 0x13, 0x14, 0x15, 0x16, 0x17, 0x18, 0x19, 0x1a, 0x1b, 0x1c, 0x1d, 0x1e, 0x1f, 0x20, 0x21, 0x22, 0x23, 0x24, 0x25, 0x26, 0x27, 0x28, 0x29, 0x2a, 0x2b, 0x2c, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x2f, 0x30, 0x31, 0x32, 0x33, 0x34, 0x35, 0x36, 0x37, 0x38, 0x39, 0x3a, 0x3b, 0x3c, 0x3d, 0x3e, 0x3f, 0x40, 0x41, 0x42, 0x43, 0x44, 0x45, 0x46, 0x47, 0x48, 0x49, 0x4a, 0x4b, 0x4c, 0x4d, 0x4e, 0x4f, 0x50, 0x51, 0x52, 0x53, 0x54, 0x55, 0x56, 0x57, 0x58, 0x59, 0x5a, 0x5b, 0x5c, 0x5d, 0x5e, 0x5f, 0x60, 0x61, 0x62, 0x63, 0x64, 0x65, 0x66, 0x67, 0x68, 0x69, 0x6a, 0x6b, 0x6c, 0x6d, 0x6e, 0x6f, 0x70, 0x71, 0x72, 0x73, 0x74, 0x75, 0x76, 0x77, 0x78, 0x79, 0x7a, 0x7b, 0x7c, 0x7d, 0x7e, 0x7f, 0x80, 0x81, 0x82, 0x83, 0x84, 0x85, 0x86, 0x87, 0x88, 0x89, 0x8a, 0x8b, 0x8c, 0x8d, 0x8e, 0x8f, 0x90, 0x91, 0x92, 0x93, 0x94, 0x95, 0x96, 0x97, 0x98, 0x99, 0x9a, 0x9b, 0x9c, 0x9d, 0x9e, 0x9f, 0xa0, 0xa1, 0xa2, 0xa3, 0xa4, 0xa5, 0xa6, 0xa7, 0xa8, 0xa9, 0xaa, 0xab, 0xac, 0xad, 0xae, 0xaf, 0xb0, 0xb1, 0xb2, 0xb3, 0xb4, 0xb5, 0xb6, 0xb7, 0xb8, 0xb9, 0xba, 0xbb, 0xbc, 0xbd, 0xbe, 0xbf, 0xc0, 0xc1, 0xc2, 0xc3, 0xc4, 0xc5, 0xc6, 0xc7, 0xc8, 0xc9, 0xca, 0xcb, 0xcc, 0xcd, 0xce, 0xcf, 0xd0, 0xd1, 0xd2, 0xd3, 0xd4, 0xd5, 0xd6, 0xd7, 0xd8, 0xd9, 0xda, 0xdb, 0xdc, 0xdd, 0xde, 0xdf, 0xe0, 0xe1, 0xe2, 0xe3, 0xe4, 0xe5, 0xe6, 0xe7, 0xe8, 0xe9, 0xea, 0xeb, 0xec, 0xed, 0xee, 0xef, 0xf0, 0xf1, 0xf2, 0xf3, 0xf4, 0xf5, 0xf6, 0xf7, 0xf8, 0xf9, 0xfa, 0xfb, 0xfc, 0xfd, 0xfe, 0xff]

word_seed_array =

[0x0000000, 0x0000001, 0x0000002, 0x0000003, 0x0000004, 0x0000005, 0x0000006, 0x0000007, 0x0000008, 0x0000009, 0x000000a, 0x000000b, 0x000000c, 0x000000d, 0x000000e, 0x000000f, 0x00000010, 0x00000011, 0x00000012, 0x00000013, 0x00000014, 0x00000015, 0x00000016, 0x00000017, 0x00000018, 0x00000019, 0x0000001a, 0x0000001b, 0x0000001c, 0x0000001d, 0x0000001e, 0x0000001f, 0x00000020, 0x00000021, 0x00000022, 0x00000023, 0x00000024, 0x00000025, 0x00000026, 0x00000027, 0x00000028, 0x00000029, 0x0000002a, 0x0000002b, 0x0000002c, 0x0000002d, 0x0000002e, 0x0000002f, 0x00000030, 0x00000031, 0x00000032, 0x00000033, 0x00000034, 0x00000035, 0x00000036, 0x00000037, 0x00000038, 0x00000039, 0x0000003a, 0x0000003b, 0x0000003c, 0x0000003d, 0x0000003e, 0x0000003f, 0x00000040, 0x00000041, 0x00000042, 0x00000043, 0x00000044, 0x00000045, 0x00000046, 0x00000047, 0x00000048, 0x00000049, 0x0000004a, 0x0000004b, 0x0000004c, 0x0000004d, 0x0000004e, 0x0000004f, 0x00000050, 0x00000051, 0x00000052, 0x00000053, 0x00000054, 0x00000055, 0x00000056, 0x00000057, 0x00000058, 0x00000059, 0x0000005a, 0x0000005b, 0x0000005c, 0x0000005d, 0x0000005e, 0x0000005f, 0x00000060, 0x00000061, 0x00000062, 0x00000063, 0x00000064, 0x00000065, 0x00000066, 0x00000067, 0x00000068, 0x00000069, 0x0000006a, 0x0000006b, 0x0000006c, 0x0000006d, 0x0000006e, 0x0000006f, 0x00000070, 0x00000071, 0x00000072, 0x00000073, 0x00000074, 0x00000075, 0x00000076, 0x00000077, 0x00000078, 0x00000079, 0x0000007a, 0x0000007b, 0x0000007c, 0x0000007d, 0x0000007e, 0x0000007f, 0x00000080, 0x00000081, 0x00000082, 0x00000083, 0x00000084, 0x00000085, 0x00000086, 0x00000087, 0x00000088, 0x00000089, 0x0000008a, 0x0000008b, 0x0000008c, 0x0000008d, 0x0000008e, 0x0000008f, 0x00000090, 0x00000091, 0x00000092, 0x00000093, 0x00000094, 0x00000095, 0x00000096, 0x00000097, 0x00000098, 0x00000099, 0x0000009a, 0x0000009b, 0x0000009c, 0x0000009d, 0x0000009e, 0x0000009f, 0x000000a0, 0x000000a1, 0x000000a2, 0x000000a3, 0x000000a4, 0x000000a5, 0x000000a6, 0x000000a7, 0x000000a8, 0x000000a9, 0x000000aa, 0x000000ab, 0x000000ac, 0x000000ad, 0x000000ae, 0x000000af, 0x000000b0, 0x000000b1, 0x000000b2, 0x000000b3, 0x000000b4, 0x000000b5, 0x000000b6, 0x000000b7, 0x000000b8, 0x000000b9, 0x000000ba, 0x000000bb, 0x000000bc, 0x000000bd, 0x000000be, 0x000000bf, 0x000000c0, 0x000000c1, 0x000000c2, 0x000000c3, 0x000000c4, 0x000000c5, 0x000000c6, 0x000000c7, 0x000000c8, 0x000000c9, 0x000000ca, 0x000000cb, 0x000000cc, 0x000000cd, 0x000000ce, 0x000000cf, 0x000000d0, 0x000000d1, 0x000000d2, 0x000000d3, 0x000000d4, 0x000000d5, 0x000000d6, 0x000000d7, 0x000000d8, 0x000000d9, 0x000000da, 0x000000db, 0x000000dc, 0x000000dd, 0x000000de, 0x000000df, 0x000000e0, 0x000000e1, 0x000000e2, 0x000000e3, 0x000000e4, 0x000000e5, 0x000000e6, 0x000000e7, 0x000000e8, 0x000000e9, 0x000000ea, 0x000000eb, 0x000000ec, 0x000000ed, 0x000000ee, 0x000000ef, 0x000000f0, 0x000000f1, 0x000000f2, 0x000000f3, 0x000000f4, 0x000000f5, 0x000000f6, 0x000000f7, 0x000000f8, 0x000000f9, 0x000000fa, 0x000000fb, 0x000000fc, 0x000000fd, 0x000000fe, 0x000000ff]

Listing 2: The byte_seed_array and word_seed_array.

Knowing that these arrays are static, an analyst could dump the arrays any time post-initialization, thus bypassing this anti‑reversing technique.

The overall framework of the in-place decryption process is:

This process is repeated in JNI_OnLoad() for each encrypted array. I did not identify the decryption algorithm used in the library as being a variation of a known encryption algorithm. The Python code I wrote to implement the decryption algorithm is shown in Listing 3.

def decrypt(encrypted_bytes, length, byte_seed_array, word_seed_array):

if (encrypted_bytes is None):

print ( "encrypted_bytes is null. -- Exiting ")

return

if (length < 1):

print ( "encrypted_bytes len < 1 -- Exiting ")

return

reg_4 = ~(0x00000004)

reg_0 = 4

reg_2 = 0

reg_5 = 0

do_loop = True

# Address 0x2F58 in Sample e8e1bc048ef123a9757a9b27d1bf53c092352a26bdbf9fbdc10109415b5cadac

while (do_loop):

reg_6 = length + reg_0

reg_6 = encrypted_bytes[reg_6 + reg_4]

if (reg_6 & 0x80):

if (reg_5 > 3):

return

reg_6 = reg_6 & 0x7F

reg_2 = reg_2 & 0xFF

reg_2 = reg_2 << 7

reg_2 = reg_2 | reg_6

reg_0 = reg_0 + reg_4 + 4

reg_3 = length + reg_0 + reg_4 + 2

reg_5 += 1

if (reg_3 & 0x80000000 or reg_3 <= 1):

return

else:

do_loop = False

reg_5 = 0xF0 & reg_6

reg_3 = length + reg_0 + reg_4

reg_1 = reg_3 + 1

if (reg_0 == 0 and reg_5 != 0):

return

# Address 0x2F9A in Sample e8e1bc048ef123a9757a9b27d1bf53c092352a26bdbf9fbdc10109415b5cadac

reg_5 = reg_1

reg_1 = (reg_2 << 7) + reg_6

byte_FF = 0xFF

reg_1 = reg_1 & byte_FF

last_byte = reg_1

if (reg_5 == 0 or reg_5 & 0x80000000 or last_byte == 0 or signed_ble(reg_3, last_byte)):

return

reg_1 = (reg_4 + 4)

reg_1 = (reg_1 * last_byte)

reg_1 += length

crazy_num = reg_1 + reg_0 + reg_4

if (crazy_num < 1):

return

new_index = reg_1 + reg_0

reg_5 = 0

# Address 0x2FD8 in Sample e8e1bc048ef123a9757a9b27d1bf53c092352a26bdbf9fbdc10109415b5cadac

while (1):

byte = encrypted_bytes[reg_5]

reg_0 = byte << 2

reg_6 = word_seed_array[byte]

reg_0 = 0xFF - reg_6

if (not reg_6 & 0x80000000):

reg_6 = reg_0

reg_0 = reg_5

reg_1 = reg_0 % last_byte

reg_0 = new_index + reg_1

reg_0 = encrypted_bytes[(reg_0 + reg_4) & 0xFF]

reg_1 = word_seed_array[reg_0]

reg_2 = reg_1 | reg_6

index_reg_0 = reg_5

if (reg_2 & 0x80000000):

break

# Address 0x3012 in Sample e8e1bc048ef123a9757a9b27d1bf53c092352a26bdbf9fbdc10109415b5cadac

reg_1 = reg_6 + reg_1 + reg_5

reg_2 = arith_shift_rt(reg_1, 0x1F)

reg_2 = reg_2 >> 0x18

reg_2 = reg_2 & ~0x000000FF

reg_1 -= reg_2

reg_1 = 0x000000FF - reg_1

reg_1 = byte_seed_array[reg_1 & 0xFF]

encrypted_bytes[index_reg_0] = reg_1 & 0xFF

reg_5 += 1

if (reg_5 >= crazy_num):

break

print "*********** FINISHED DECRYPT *************** "

Listing 3: Python code to implement the decryption algorithm.

I wrote an IDAPython script to statically decrypt the contents of the ELF so that reverse engineering could continue. This script and description is provided in the Appendix.

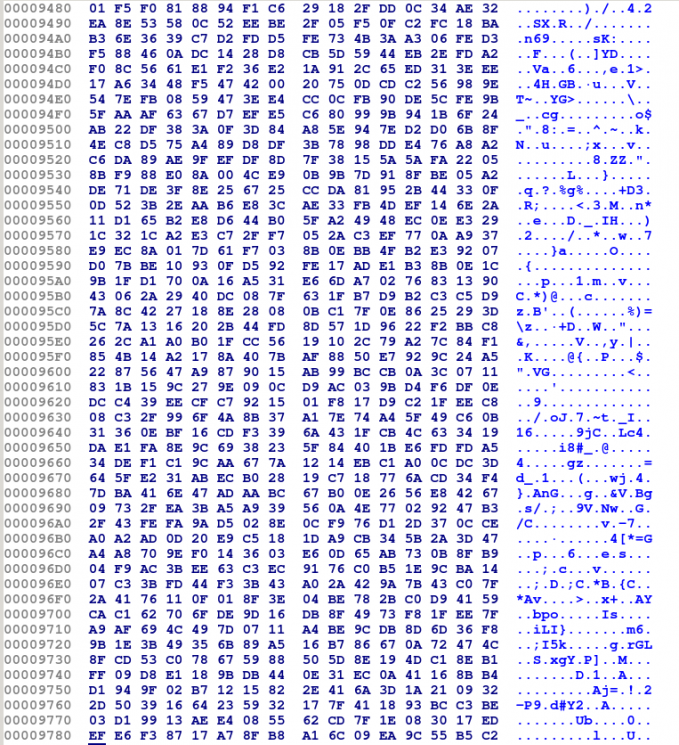

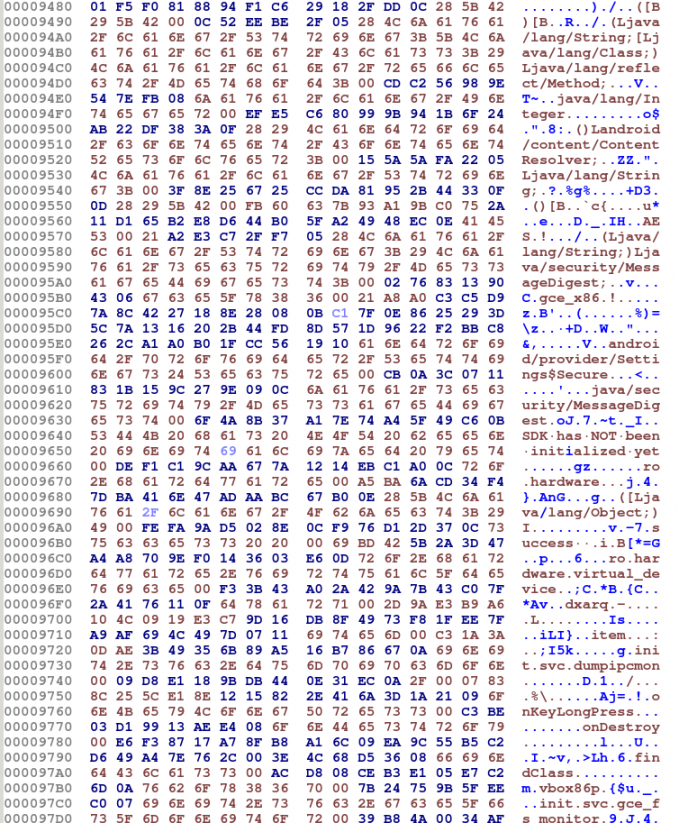

Each of the encrypted arrays decrypts to a string. Before-and-after samples of the encrypted bytes and the decrypted bytes at 0x9480 are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The bytes were decrypted using the IDAPython decryption script described in the Appendix.

Figure 3: Encrypted bytes in ELF beginning at 0x9480.

Figure 3: Encrypted bytes in ELF beginning at 0x9480.

Figure 4: Decrypted bytes in ELF beginning at 0x9480.

Figure 4: Decrypted bytes in ELF beginning at 0x9480.

Within the decrypted strings of the ELF, we see the names of the native functions defined in the Java code at the following locations in the ELF file:

Now that these strings are decrypted, we can see which subroutines in the ELF are called when the native function is called from the APK. Table 2 shows the native functions defined for this sample in the anti-analysis ELF.

| Native function name | Native subroutine address | Signature | Human-readable signature |

| vxeg | 0x30D4 | ([Ljava/lang/Object;)I | public native int vxeg(Object[] p0); |

| quaqrd | 0x4814 | (I)Ljava/lang/String; | public static native String quaqrd(int p0); |

| ixkjwu | ---- | ([Ljava/lang/Object;)Ljava/lang/Object; | public native Object ixkjwu(Object[] p0); |

Table 2: Native functions in the anti-analysis library.

The Java-declared native method that has the same signature as vxeg has in this sample (([Ljava/lang/Object;)I), is responsible for doing all of the run-time environment checks described in the next section. In each sample, this function is named differently due to the automatic obfuscator run on the Java code, but it always has this signature. For clarity, the rest of this paper will refer to the native subroutine that performs all of the run-time checks as vxeg().

The Java-declared native method that has the same signature as quarqrd has in this sample ((I)Ljava/lang/String;) returns a string from an array. The argument to the method is the index into the array and the address of the array is hard coded into the native subroutine. The strings in this array are decrypted by the decryption function described above.

Via static reverse engineering, I did not determine the native subroutine corresponding to the ixkjwu method. In the Java code, the ixkjwu method is only called in one place and is only called based on the value of a variable. It is possible that this method is never called based on the value of that variable and thus the ixkjwu native subroutine does not exist.

vxeg and quarqrd are registered with the RegisterNatives JNI method at 0x2B60 in this sample. The array at 0x9048 is used for this call to RegisterNatives. It includes the native method name, signature, and pointer to the native subroutine as shown below. The code at 0x2B42, prior to the call to RegisterNatives, shows that this subroutine can support the following array entries for three native methods instead of the two that exist in this instance.

0x9048: Pointer to vxeg string

0x904C: Pointer to vxeg signature string

0x9050: 0x30D5 (Pointer to subroutine)

0x9054: Pointer to quarqrd string

0x9058: Pointer to quarqrd signature string

0x905C: 0x4815 (Pointer to subroutine)

The rest of this paper will focus on the functionality found in vxeg() because it contains the anti-analysis run-time environment checks.

The Java classes associated with WeddingCake in the APK define three native functions in the Java code. In this sample vxeg()performs all of the run-time environment checks prior to performing the hidden behaviour. This function performs more than 45 different run-time checks. They can be grouped as follows:

If the library detects any of the conditions outlined in this section, the Linux exit(0) function is called, which terminates the Android application [8]. The application stops running if any of the 45+ environment checks fail.

The vxeg() subroutine begins by checking the values of the listed system properties. The system_property_get() function is used to get the value of each system property checked. The code checks if the value matches the listed value for each property. If any one of the system properties matches the listed value, the Android application exits. Table 3 lists each of the system properties that is checked and the value which will trigger an exit.

| System property checked | Value(s) that trigger exit |

| init.svc.gce_fs_monitor | running |

| init.svc.dumpeventlog | running |

| init.svc.dumpipclog | running |

| init.svc.dumplogcat | running |

| init.svc.dumplogcat-efs | running |

| init.svc.filemon | running |

| ro.hardware.virtual_device | gce_x86 |

| ro.kernel.androidboot.hardware | gce_x86 |

| ro.hardware.virtual_device | gce_x86 |

| ro.boot.hardware | gce_x86 |

| ro.boot.selinux | disable |

| ro.factorytest | true, 1, y |

| ro.kernel.android.checkjni | true, 1, y |

| ro.hardware.virtual_device | vbox86 |

| ro.kernel.androidboot.hardware | vbox86 |

| ro.hardware | vbox86 |

| ro.boot.hardware | vbox86 |

| ro.build.product | google_sdk |

| ro.build.product | Droid4x |

| ro.build.product | sdk_x86 |

| ro.build.product | sdk_google |

| ro.build.product | vbox86p |

| ro.product.manufacturer | Genymotion |

| ro.product.brand | generic |

| ro.product.brand | generic_x86 |

| ro.product.device | generic |

| ro.product.device | generic_x86 |

| ro.product.device | generic_x86_x64 |

| ro.product.device | Droid4x |

| ro.product.device | vbox86p |

| ro.kernel.androidboot.hardware | goldfish |

| ro.hardware | goldfish |

| ro.boot.hardware | goldfish |

| ro.hardware.audio.primary | goldfish |

| ro.kernel.androidboot.hardware | ranchu |

| ro.hardware | ranchu |

| ro.boot.hardware | ranchu |

Table 3: System properties checked and the values that trigger exit.

The anti-analysis library also checks if any of five system properties exist on the device using the system_property_find() function. If any of these five system properties exist, the Android application exits. The properties that the library searches for are listed in Table 4. The presence of any of these properties usually indicates that the application is running on an emulator.

| If any of these system properties exist, the application exits |

| init.svc.vbox86-setup |

| qemu.sf.fake_camera |

| init.svc.goldfish-logcat |

| init.svc.goldfish-setup |

| init.svc.qemud |

Table 4: System properties checked for using system_property_find.

If the library has passed all of the system property checks, it (still in vxeg()) then verifies the CPU architecture of the phone on which the application is running. In order to verify the CPU architecture, the code reads 0x14 bytes from the beginning of the /system/lib/libc.so file on the device. If the read is successful, the code looks at the bytes corresponding to the e_ident[EI_CLASS] and e_machine fields of the ELF header. e_ident[EI_CLASS] is set to 1 to signal a 32-bit architecture and set to 2 to signal a 64-bit architecture. e_machine is a 2-byte value identifying the instruction set architecture. The code will only continue if one of the following statements is true. Otherwise, the application exits:

The anti-analysis library is verifying that it is only running on a 32-bit ARM or 64-bit AArch64 CPU. Even when the library is running its x86 variant, it still checks whether the CPU is ARM and will exit if the detected CPU is not ARM or AArch64.

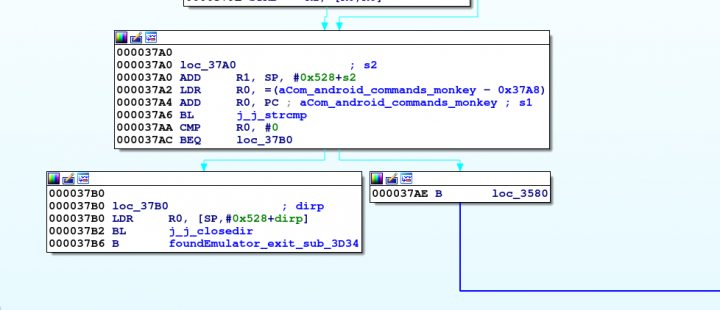

After the CPU architecture check, the library attempts to iterate through every PID directory under /proc/ to determine if com.android.commands.monkey is running [6]. The code does this by opening the /proc/ directory and iterating through each entry in the directory, completing the following steps. If any step fails, execution moves to the next entry in the directory.

If the check for Monkey is ever true, exit() is called, closing the Android application (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Check for Monkey.

Figure 5: Check for Monkey.

This method of iterating through each directory in /proc/ doesn't work in Android N and above [9]. If the library is not able to iterate through the directories in /proc/ it will continue executing.

The Xposed Framework allows hooking and modifying of the system code running on an Android device. This library ensures that the Xposed Framework is not currently mapped to the application process. If Xposed is running the process, it could allow for some of the anti-analysis techniques to be bypassed. If the library did not check for Xposed and allowed the application to continue running when Xposed was hooked to the process, an analyst could instrument the application to bypass the anti-analysis hurdles and uncover the functionality that the application author is trying to hide.

In order to determine if Xposed is running, the library, checks if 'LIBXPOSED_ART.SO' or 'XPOSEDBRIDGE.JAR' exist in /proc/self/maps. If either of them exist, then the application exits. /proc/self/maps lists all of the memory pages mapped into the process memory. Therefore, you can see any libraries loaded by the process by reading its contents.

To further verify that the Xposed Framework is not running, the code will check if either of the following two classes can be found using the JNI FindClass() function [10]. If either class can be found, the application exits:

If the Xposed library is not found, the execution continues to the behaviour that the anti-analysis techniques were trying to protect. This behaviour continues in vxeg(). In the case of this sample, it was another unpacker that previously had not been protected by the anti-reversing and analysis techniques described in this paper.

This paper detailed the operation of WeddingCake, an Android native library using extensive anti-analysis techniques. Unlike previous packers' anti-emulation techniques, this library is written in C/C++ and runs as a native shared library in the application. Once an analyst understands the anti-reversing and anti-analysis techniques utilized by an application, they can more effectively understand its logic and analyse and detect potentially malicious behaviours.

[1] Detecting and eliminating Chamois, a fraud botnet on Android. Android Developers Blog. https://android-developers.googleblog.com/2017/03/detecting-and-eliminating-chamois-fraud.html.

[2] Getting Started with the NDK. Android. https://developer.android.com/ndk/guides/.

[3] JNI Tips. Android. https://developer.android.com/training/articles/perf-jni.

[4] Resolving Native Method Names. Oracle. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/6/docs/technotes/guides/jni/spec/design.html#wp615.

[5] Registering Native Methods in JNI. Stack Overflow. https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1010645/what-does-the-registernatives-method-do.

[6] UI/Application Exerciser Monkey. Android. https://developer.android.com/studio/test/monkey.

[7] Xposed General. XDA Developers Forum. https://forum.xda-developers.com/xposed.

[8] EXIT(3). Linux Programmer's Manual. http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/exit.3.html.

[9] Enable hidepid=2 on /proc. Android Open Source Project. https://android-review.googlesource.com/c/platform/system/core/+/181345.

[10] JNI Functions. Oracle. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/technotes/guides/jni/spec/functions.html#FindClass.

In order to decrypt the encrypted portions of the ELF library that the decryption function (for this sample, sub_2F30) decrypts during execution, I created an IDAPython script to decrypt the ELF. This script is available at http://www.github.com/maddiestone/IDAPythonEmbeddedToolkit/Android/WeddingCake_decrypt.py. By decrypting the ELF with the IDAPython script, it's possible to statically reverse engineer the behaviour that is hidden under the anti-analysis techniques. This section describes how the script works.

The IDAPython decryption script runs the following steps:

The script was written to dynamically identify each of the encrypted arrays and their lengths from an IDA Pro database. This allows it to be run on many different samples without an analyst having to define the encrypted byte arrays. Therefore, the IDAPython script is dependent on the library's architecture. This script will run on the 32-bit 'generic' ARM versions of the library. For the other variants of the library mentioned in the 'Variants' section (ARMv7, ARM64, and x86), the same decryption algorithm in the script can be used, but the code to find the encrypted arrays and lengths will not run.

Once the script has finished running, the analyst can reverse engineer the native code as it lives when executing with the decrypted string.