ESET, Slovakia

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

Hacking Team first came under the spotlight of the security industry following its damaging data breach in July 2015. The leaked data revealed several zero-day exploits being used and sold to governments, and confirmed suspicions that Hacking Team had been doing business with oppressive regimes. But what happened to Hacking Team after one of the most famous hacks of recent years?

Hacking Team's flagship product, the Remote Control System (RCS), was detected in the wild at the beginning of 2018 in 14 different countries, including some of those that had previously criticized the company's practices. In this paper, we will present the evidence that convinced us that the new, post-hack Hacking Team samples can be traced back to a single group – not just any group, but Hacking Team's developers themselves.

Furthermore, we will share previously undisclosed insights into Hacking Team's post-leak operations, including the targeting of diplomats in Africa, uncover the digital certificates used to sign the malware, and share details of the distribution vectors used to target the victims. We will compare the functionality of the post-leak samples with that of the leaked source code. To help other security researchers, we'll provide tips on how to efficiently extract details from these newer VMProtect-packed RCS samples. Finally, we will show how Hacking Team sets up companies and purchases certificates for them.

Since being founded in 2003, the Italian spyware vendor Hacking Team has gained notoriety for selling surveillance tools to governments and their agencies across the world. The capabilities of its flagship product, the Remote Control System (RCS), include extracting files from a targeted device, intercepting emails and instant messaging, as well as remotely activating a device's webcam and microphone. The company has been criticized for selling these capabilities to authoritarian governments [1] – an allegation it has consistently denied.

When Hacking Team itself suffered a damaging hack in July 2015 [2], the reported use of RCS by oppressive regimes was confirmed [3].

The 400GB of leaked internal data included:

Due to the severity of the leak, Hacking Team was forced to ask its customers to suspend all use of RCS, and was left facing an uncertain future.

The security community has been keeping a close eye on the company's efforts to get back on its feet. With both the source code and a ready-to-use builder leaked, it came as no surprise when cybercriminals started reusing the spyware. This was the case in January 2016, when Callisto Group reused the source code in one of their campaigns [4]. Recent reports have revealed that in June 2016, Hacking Team received funding from a mysterious investor with ties to Saudi Arabia [5].

In the early stages of our investigation, the Citizen Lab provided us with RCS samples used in 2016 and 2017, which led to the discovery of a version of the spyware currently being used in the wild and signed with a previously unseen valid digital certificate.

Our further research uncovered several more samples of Hacking Team's spyware created after the 2015 hack, all being slightly modified compared to variants released before the source code leak.

The samples were compiled between September 2015 and October 2017. We have deemed these compilation dates to be authentic, based on ESET telemetry data indicating the appearance of the samples in the wild within a few days of those dates.

All the samples are packed with VMProtect, a commercial anti-piracy protector, which was also the case with pre-leak samples. We notified VMProtect's developers and asked them to blacklist the licence used to pack spyware, but no action was taken.

In this section, we will explain how we unpacked the samples of modified Hacking Team spyware.

There are two approaches – the first is intended to extract only some (valuable) details from the sample, such as the C&C; the second approach is to fully unpack the sample, including rebuilding the IAT (Import Address Table). The first approach is obviously easier and quicker, but to be able to fully analyse the samples, the second approach is needed.

For the first approach, the sample is run and after some time, when the sample unpacks itself, the process is dumped. Then the C&C or other information can be searched for in the dump. Indeed, this is not a sophisticated method, but it is important to mention this easy but still effective approach. For dumping you can use:

The second approach represents typical unpacking, and results in a fully working unpacked PE file. We unpacked the sample dynamically (i.e. by executing it).

This approach includes the following steps:

The steps explained in detail:

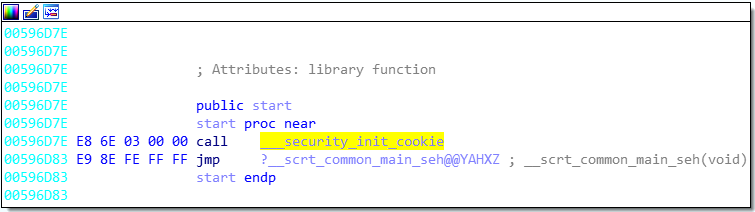

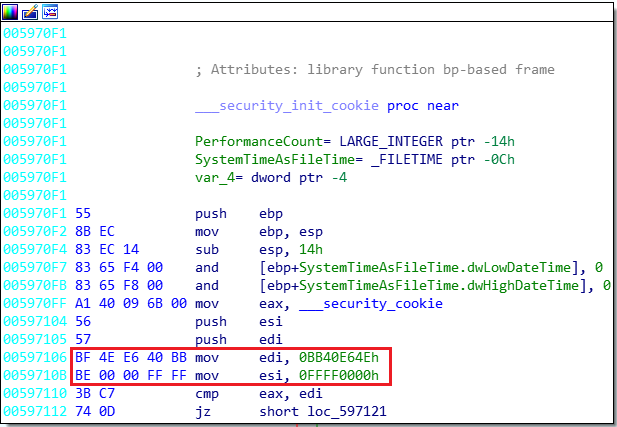

Figure 1: Typical bytes on entry point in programs compiled with Microsoft Visual Studio.

Figure 1: Typical bytes on entry point in programs compiled with Microsoft Visual Studio.

As for the distribution vector of the post-leak samples we analysed, in at least two cases, we detected the spyware in an executable file disguised as a PDF document. The names of the files suggest the malware was spread via spear-phising emails sent to high-profile targets such as diplomats:

Our systems have detected these new Hacking Team spyware samples in 14 countries. We choose not to name the countries in order to prevent potentially incorrect attributions based on these detections, since the geo-location of the detections doesn't necessarily reveal anything about the origin of the attack.

The malware has two stages – Scout (first stage) and Soldier or Elite (second stage; regular and premium version). The second stage, the actual payload, is deployed after a few initial checks carried out by Scout.

In the post-leak samples we analysed, Scout and Soldier had the following functionality:

{"camera":{"enabled":false,"repeat":0,"iter":0},"position":{"enabled":false,"repeat":0},"screenshot":

{"enabled":true,"repeat":120},"photo":{"enabled":false},"file":{"enabled":false},"addressbook":{"enabled"

:false},"chat":{"enabled":false},"clipboard":{"enabled":false},"device":{"enabled":true},"call":{"enabled"

:false},"messages":{"enabled":false},"password":{"enabled":false},"keylog":{"enabled":false},"mouse":

{"enabled":false},"url":{"enabled":false},"sync":{"host":"149.154.153.223","repeat":120},"uninstall":

{"date":null,"enabled":false}}

Further analysis led us to conclude that all the analysed post-leak samples can be traced back to a single group, rather than being isolated instances of diverse actors building their own versions from the leaked Hacking Team source code.

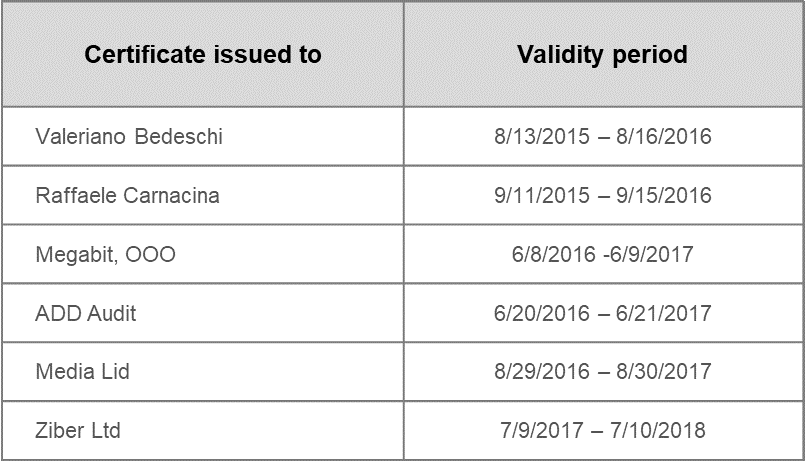

One indicator supporting this is the sequence of digital certificates used to sign the samples – we found six different certificates issued in succession. Four of the certificates were issued by Thawte to four different companies, and two are personal certificates issued to Valeriano Bedeschi (Hacking Team co-founder) and someone named Raffaele Carnacina.

Figure 2: The sequence of digital certificates used to sign the post-leak samples. Samples signed by Valeriano Bedeschi were most likely used for testing purposes, as the C&C was set to an internal network (172.16.1.206).

Figure 2: The sequence of digital certificates used to sign the post-leak samples. Samples signed by Valeriano Bedeschi were most likely used for testing purposes, as the C&C was set to an internal network (172.16.1.206).

The versioning observed in the analysed samples continues where Hacking Team left off before the breach, and follows the same patterns. Hacking Team's habit of compiling Scout and Soldier consecutively, and often on the same day, can also be seen across the newer samples.

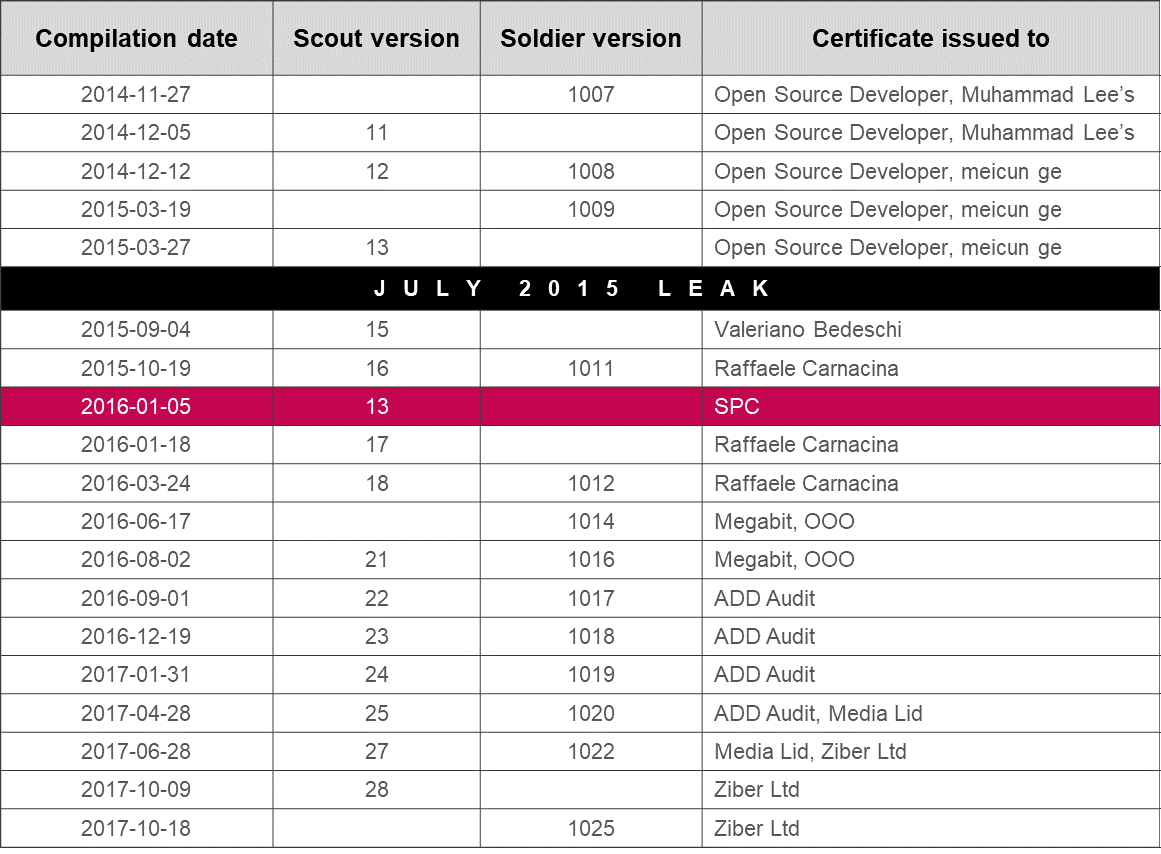

Figure 3 shows the compilation dates, versioning and certificate authorities of Hacking Team Windows spyware samples seen between 2014 and 2017. Post-leak samples with renewed versioning begin with the sample signed by Valeriano Bedeschi. Reuse of the leaked source code by Callisto Group is marked in red.

Figure 3: Hacking Team Windows spyware samples seen between 2014 and 2017.

Figure 3: Hacking Team Windows spyware samples seen between 2014 and 2017.

Furthermore, our research has confirmed that the changes introduced in the post-leak updates were made in line with Hacking Team's own coding style. The changes are often found in places that indicate a deep familiarity with the code, and follow Hacking Team's previously established development patterns (visible in the leaked source code).

Other than these specific changes, the majority of the code is without any modifications. It is highly improbable that some other actor – that is, other than the original Hacking Team developer(s) – would make changes in exactly these places when creating new versions from the leaked Hacking Team source code.

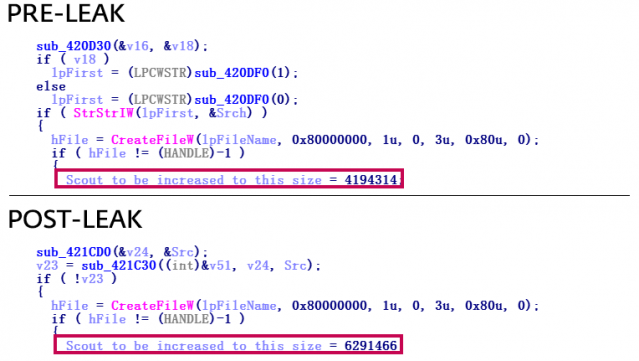

As shown in Figure 4, one of the subtle differences between the pre-leak and post-leak samples is a difference in Startup file size. When Scout installs on the system, it copies itself into the Windows Startup folder and appends random data to the end of the binary. This trick was used as an evasive technique against one anti-virus product. Before the leak, the copied file was padded to occupy 4MB. In the post-leak samples, this file copy operation is padded to 6MB.

Figure 4: Startup file size copy changed from 4MB pre-leak to 6MB post-leak.

Figure 4: Startup file size copy changed from 4MB pre-leak to 6MB post-leak.

Scout samples from before the leak used the GetTickCount and Rand functions to generate random numbers for increasing their size by appending the numbers at the end of the binary. In the post-leak samples, the number generation has been improved by using the CryptGenRandom API function. Only if this function fails are the previous functions used.

3. Changes in MySleep function

Hacking Team developers used their own MySleep function – in the samples from before the leak, it was implemented for bypassing sleep patches in many sandboxes. It consisted of the GetCurrentThread and WaitForSingleObject Windows API functions. In the post-leak samples, the MySleep function is still present, but now comprises the CreateEvent, WaitForSingleObject and CloseHandle Windows API functions.

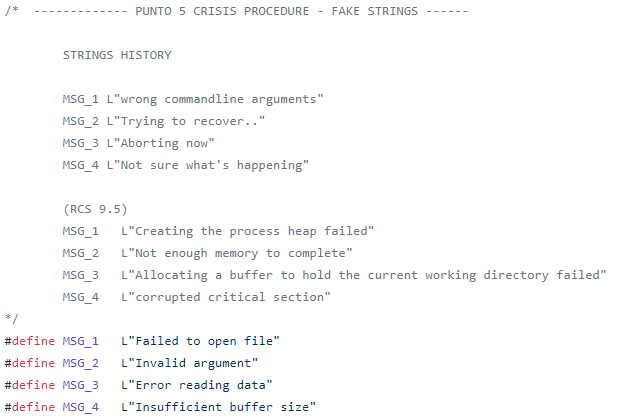

The pre-leak samples contain fake error message strings to be used in case the spyware is run with a system process ID (i.e. 0 or 4). A process executed by a regular user would never have these ID values, so this trick might be aimed at sandboxes or emulators.

The content of the fake error messages had been changed regularly before the leak; the history of these changes was revealed in the leaked source code (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Fake strings history in the Scout leaked source code. RCS 9.5 includes Scout versions 11 and 12.

Figure 5: Fake strings history in the Scout leaked source code. RCS 9.5 includes Scout versions 11 and 12.

In the post-leak samples, the strings have been changed again, this time to the message 'Aborting now'.

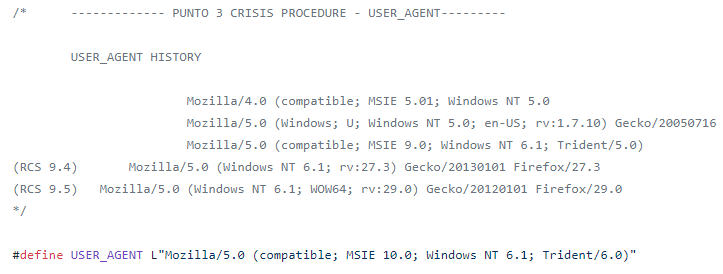

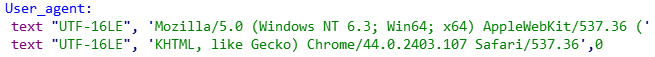

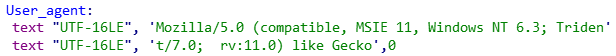

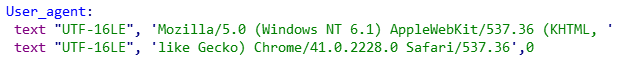

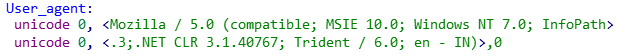

Compared to pre-leak samples, some of the parameters of the user-agent string used for HTTP protocol when communicating with the C&C server are different in the newer samples. (See Figures 6 to 10.)

Figure 6: User-agent string history in the Scout leaked source code. RCS 9.4 includes Scout version unknown; RCS 9.5 includes Scout versions 11 and 12.

Figure 6: User-agent string history in the Scout leaked source code. RCS 9.4 includes Scout version unknown; RCS 9.5 includes Scout versions 11 and 12.

Figure 7: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 15.

Figure 7: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 15.

Figure 8: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 17.

Figure 8: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 17.

Figure 9: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 22.

Figure 9: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 22.

Figure 10: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 28.

Figure 10: Altered user-agent string in Scout version 28.

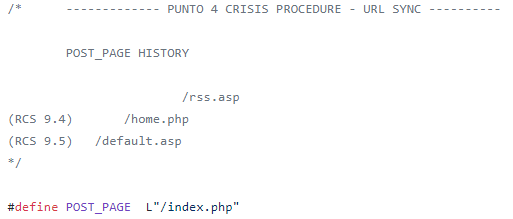

The URL path used for HTTP protocol when communicating with the C&C server is another part of the code that was frequently changed in the pre-leak samples. In the post-leak samples, these paths also vary from sample to sample.

Figure 11: Strings used from C&C sync in the Scout leaked source code. RCS 9.4 includes Scout version unknown.; RCS 9.5 includes Scout versions 11 and 12.

Figure 11: Strings used from C&C sync in the Scout leaked source code. RCS 9.4 includes Scout version unknown.; RCS 9.5 includes Scout versions 11 and 12.

![]() Figure 12: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 15.

Figure 12: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 15.

![]() Figure 13: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 17.

Figure 13: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 17.

![]() Figure 14: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 18.

Figure 14: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 18.

![]() Figure 15: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 28.

Figure 15: Alter URL Sync string in Scout version 28.

None of these indicators, by themselves, represents conclusive evidence of Hacking Team's renewed activity. However, viewing them as a whole lets us claim with high confidence that, with one obvious exception, the post-leak samples we've analysed are indeed the work of the Hacking Team developers, and not the result of source code reuse by unrelated actors, such as in the case of Callisto Group in 2016.

[1] The Citizen Lab. Mapping Hacking Team's "Untraceable" Spyware. February 2014. https://citizenlab.ca/2014/02/mapping-hacking-teams-untraceable-spyware/.

[2] Franceschi-Bicchierai, L. Spy Tech Company 'Hacking Team' Gets Hacked. Motherboard. July 2015. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/gvye3m/spy-tech-company-hacking-team-gets-hacked.

[3] Hern, A. Hacking Team hacked: firm sold spying tools to repressive regimes, documents claim. The Guardian. July 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/06/hacking-team-hacked-firm-sold-spying-tools-to-repressive-regimes-documents-claim.

[4] F-Secure Labs. Callisto Group. April 2017. https://www.f-secure.com/documents/996508/1030745/callisto-group.

[5] Franceschi-Bicchierai, L. Hacking Team Is Still Alive Thanks to a Mysterious Investor From Saudi Arabia. Motherboard. January 2018. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/8xvzyp/hacking-team-investor-saudi-arabia.