AhnLab, South Korea

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

The Sony Pictures hack occurred in 2014, and the news that the company's internal data had been destroyed and confidential data had been leaked was publicized worldwide. When Korean malware researchers first heard about the attack, they recalled the attacks against Korean banks and media companies between 2011 and 2013, but they didn't anticipate a connection with this attack. When more information on the malware was released, it came as quite a surprise to find that it contained similar code to malware that had already been found in Korea.

The Lazarus Group, which includes Red Dot and Labyrinth Chollima, became well known to the press and the security community outside of Korea because of the Sony Pictures hack. Malicious code that is similar to the code used in the Sony Pictures hack is still being used in targeted attacks on Korean companies and institutions. In 2015, a zero-day exploit targeted the participants of the Seoul ADEX 2015 conference using a Hangul vulnerability, and in 2016, a Windows zero-day vulnerability was used to hack various ICT companies and web-hosting providers. The group is also suspected of attacking a cryptocurrency exchange.

In this paper, I will describe various attacks in Korea which occurred after the Sony incident and are suspected to be the work of the Lazarus Group. I will also analyse and discuss the changes seen in the malware code.

In November 2014, Sony Pictures Entertainment was the target of a cyber attack that resulted in the destruction of its system data and the release of internal emails and upcoming movies. When detailed information about the incident was revealed, malware analysts in South Korea discovered a strong correlation between this malware and the malware that had been used in recent cyber attacks in South Korea. It was later announced by the US government that the group behind the Sony attack was linked to the Lazarus Group, which is mainly active in South Korea.

The governmental institutions of Korea have been under continuous cyber attack from unidentified attackers since 2007. There is a connection between these attackers and the group behind the attack on Sony Pictures. Lazarus Group, otherwise known as Hidden Cobra, is also known to have been behind the hacking of the Bangladesh Central Bank in 2016 [1] and a series of hacking incidents targeting cryptocurrencies and casinos in 2017. Meanwhile, the Bluenoroff group, a subgroup of the Lazarus Group, is more focused on attacking financial institutions and cryptocurrency exchanges. Another subgroup, Andariel, is active only in South Korea and seeks to perform various attacks that focus on stealing confidential data from the military and defence industries. Andariel was responsible for causing server errors in the 3.20 (DarkSeoul) attack on 20 March 2013, and since the second half of 2016 it has been more focused on attacking the financial industry. The activities of the Lazarus Group have been reported not only in Korea but in a number of countries [2, 3].

This report provides insights into the malware used in the Sony Pictures hacking incident and the changes seen in the malware used in attacks in Korea before and after the incident. Note that this report is based on the publicly released information and not on the results of an AhnLab investigation. As the group has a long history of attacks and malware, the report focuses specifically on the activities of Lazarus in relation to the Sony Pictures hack.

On 24 November 2014, Sony Pictures was attacked by a hacker group which identified itself as the Guardians of Peace (GOP). The attack destroyed internal system data and leaked a slew of confidential data including internal emails and yet to be released films. Sony Pictures was in the process of making a film that depicts the assassination of Kim Jong-eun, so the possibility of the attack having a link to North Korea was speculated from early on [4]. Moreover, shortly afterwards, a British TV company that was engaged in making a drama about a British nuclear scientist on a covert mission to North Korea was hacked by North Korea and production of the drama was cancelled [5]. The US government released their findings on the malware used in the Sony hack in December 2014 through the FBI and US-CERT [6]. In February 2016, Novetta published the 'Operation Blockbuster' [7] report and, in May 2016, Blue Coat published a report entitled 'From Seoul To Sony' [8] on their findings. The findings show that the attack methods of the malware used in the Sony Pictures hack were similar to those used by the Lazarus Group, so it is beyond speculation that North Korea was behind the attack.

The released results contained information on the backdoors, known as Escad, used in the attack.

| SHA256 | MD5 |

| eff542ac8e37db48821cb4e5a7d95c044fff27557763de3a891b40ebeb52cc55 | 6467c6df4ba4526c7f7a7bc950bd47eb |

| 4c2efe2f1253b94f16a1cab032f36c7883e4f6c8d9fc17d0ee553b5afb16330c | e904bf93403c0fb08b9683a9e858c73e |

The backdoors have the following features in common:

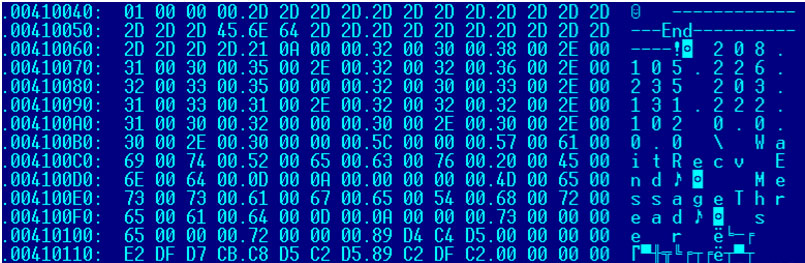

Figure 1: IP address of the C&C server.

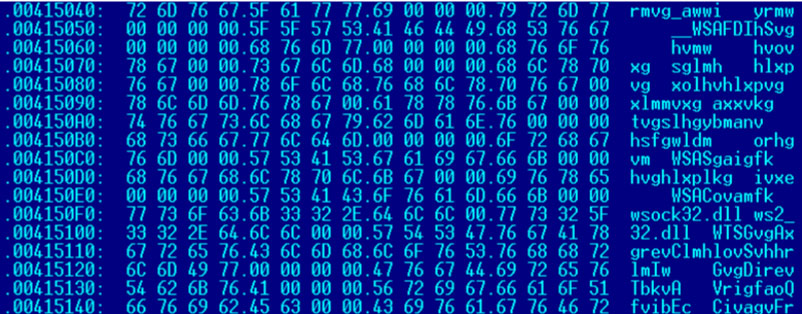

Figure 2: Specific strings of the backdoor known as Escad.

So, when was the first appearance of this malware? AhnLab found similar malware being used in attacks as early as April 2011. This malware not only includes dots in the API address like the backdoors used in the Sony attack, but some variants even use the same key value (0xA7) for decryption.

| SHA256 | MD5 |

| 37be47f8df3c94d365d693855d1af5ac8b94eedd1b3b3122586a6d48611230bb | 49ace8a624dd22f3110f041a324d1646 |

| 8c2b014f0ad27a3a325f15c916cdc9f5963ad4276e9fc928817387c0e5dc62bd | d306065bab5b742f669bb1efcebaed3a |

The droppers discovered in April 2011 include dots and perform XOR encryption with the 0xA7 key, identical to the malware used in the Sony Pictures hack, to decrypt passwords. These droppers have the unique characteristic of the string 'BMZA'; text strings containing 'BM' are also found in other malware from the Lazarus Group.

The self-delete batch file is the same as that of the Redobot backdoor:

:L1

del "C:\work\RP0.exe"

if exist "_RP0.exe" goto L1

del "C:\DOCUME~1\ADMINI~1\LOCALS~1\Temp\msvcrt.bat"

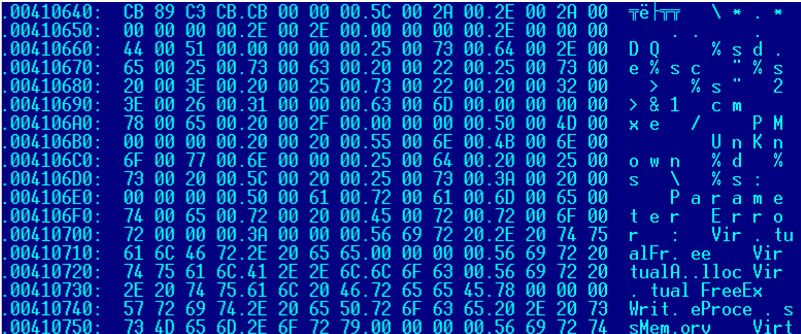

Redobot is a backdoor that was known to be in the wild between April 2011 and April 2014. This backdoor is in a DLL file format, uses API addresses that are obfuscated with dots, and contains unique text strings such as '%sd.e%sc %s 2>%s' and '%sd.e%sc %s > %s 2>&1', as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Unique text string of Redobot.

Figure 3. Unique text string of Redobot.

Some malware samples use dots as well as dashes (-) and angle brackets (<) for API obfuscation. But there are also variations without any obfuscation (b7f2595dd62d1174ce6e5ddf43bf2b42f7001c7a4ec3c4cbe3359e30c674ed83_0092f2d519739f8978cb940af0d7cca6).

Droppers that generate these DLL files were also discovered.

| SHA256 | MD5 |

| b039383a19e3da74a5a631dfe4e505020a5c5799578187e4ccc016c22872b246 | 0fe856d398c877ba0cb7019e983b5c84 |

| 218ee208323dc38ebc7f63dba73fac5541b53d7ce1858131fa3bfd434003091d | cffb5d8fc73d9e7cc5860bd6f3177b1c |

| 58b7cd75f61f6e8d3f270582a06808ce7ea77792537a102c36daf68260b43bfc | d1aaf2f58def16caac1c8d3cb46df9f4 |

| 11e9adc037b0409d0512504f348c2ffa064b418651c104f9ddddd8a12448bd06 | 6e1e06b63fca99fe97e2e341cec0efa |

| 4ef025dd920c952595b5107ba5eaf89e3caedd2ae860754159c746d1c74743ab | 65da2d2c6726c05fc863c81a2b114c2a |

Commonly, the file names were: wines.dll, winsec.dll, rdmgr.dll, tcpsys.dll, svcmgr.dll, rnamsvc.dll, httpcmgr.dll, icmpsec.dll and netmag.dll.

Table 1 shows the confirmed cases of attacks.

| Time discovered | Attack target | Attack method | Description |

| 5 July 2011 | University | ? | |

| 11 April 2014 | Medical institution | ? | Sample of one of the pieces of malware linked to WannaCry (reported by Symantec [9]) Keylogger was also found |

Table 1: List of Redobot (KorDllbot) attacks.

A report by Symantec found that the malware that attacked a medical institution in April 2014 was linked to WannaCry [9].

An early version of the Escad backdoor, which dates from as early as April 2014, used dots in the main text strings and encrypted its DLL file name using XOR 0xA7 encryption. This particular version is registered on the service and run by an executable dropper as an EXE file. The file length is around 100KB and it was not discovered until the spring of 2015.

| SHA256 | MD5 |

| 258beb2a8d7df3c55cff946a36677350dcf9317aa426d343a67e616ca7540a52 | c44a91c69d8275e4173893499beb9315 |

| 3e221003d89b629f3d9a9a75e5af90bf3d8d8c245e0b50ca4a34641ded4a44a2 | a5220e91d8daca4a6a6a75151efb8339 |

Often, malware impersonates a Microsoft Office file. The first variant of Escad to be discovered, in June 2014, infected systems using a dropper disguised as a screensaver installer.

| Time discovered | Attack target | Attack method | Description |

| June 2014 | ? | Fake screensaver installer |

Table 2: Early Escad attacks.

| SHA256 | MD5 |

| bf711a9967824bfe06d061af2c3edf077151e78a4fbc2c094065f3b0861afd05 | 310f5b1bd7fb305023c955e55064e828 |

| d36f79df9a289d01cbb89852b2612fd22273d65b3579410df8b5259b49808a39 | bce2cf667396b79f6df3475dc2b1d63a |

| 6a9919037dd2111300e62493e3c8074901ec98232e5d9fc47ca2f93ca8ba4dc2 | 964bf53c43c9168a3fa6dc6392cb3332 |

Variants of the malware used in the Sony Pictures hack were found in attacks which targeted the websites of North Korean research and governmental organizations, and the South Korean defence industry. AhnLab refers to these attacks – which occurred from 2014 to 2015 – as Operation Red Dot. The variants in this operation share similar code and names, such as AdobeArm.exe and msnconf.exe.

The main infection methods are: executable files disguised as document files (HWP, PDF), disguised installers, and exploits of Hangul Word Processor (HWP) file vulnerabilities.

The document files, which are listed in Table 3, are decoys disguised as legitimate documents, such as address books, deposit slips and invitations to lure victims into opening them.

| Original filename | English translation |

| Udb 2015-04호(4.10).exe | Data brief of a URI research and consulting company, April 2015 version |

| 김무성 문재인 차기 대선 양강 체제 구축.pdf.exe | Kim Moo-sung and Moon Jae-in are the two top candidates in the next presidential election |

| 세종국가전략연수과정 19기 주소록.exe | Address book for the 10th National Strategy Training Program of the Sejong Institute |

| 송금증.hwp.exe | Deposit slip |

| 한국행정학회 학술대회 웹 초청장 최종.exe | Final_Web invitation for the Korean Association for the Public Administration International Conference |

| 황교안 총리 지명 이후 당청 지지율 회복세.pdf.exe | Approval rating of Hwang Kyo-ahn is recovering after being nominated as prime minister |

Table 3: Decoy files disguised as legitimate files.

The file names used in the Escad variant are: adobe.exe, AdobeArm.exe, AdobeFlash.exe, msdtc.exe and msnconf.exe.

Following the Sony Pictures hack in November 2014, Operation Red Dot started to persistently attack the defence industry and government institutions of South Korea, beginning in spring 2015.

| Date | Attack target | Attack method | Description |

| November 2014 | Sony Pictures | ? | Sample for the Sony Pictures hack. This sample was first uploaded to VirusTotal in August 2014 but had been discovered in July 2014 in Korea. |

| March 2015 | Political organization (?) | Installer of a security program | Fake installer of a security program. |

| April 2015 | Defence industry | Executable file disguised as a document file | Disguised as a deposit slip. First report of Duuzer. |

| April 2015 | Political organization | Executable file disguised as a document file | Masqueraded as a web invitation for a Korean Association for Public Administration (KAPA) conference. Similar to an attack code sample for the Sony Pictures hack. |

| May 2015 | Political organization | Executable file disguised as document file | Masqueraded as a document file relating to a presidential election. |

| July 2015 | Conglomerate | ? | Variant of Duuzer. |

| August 2015 | Government | ? | Variant of Duuzer. |

| September 2015 | Defence industry | HWP Vulnerability | Loader-type malware. |

| September 2015 | ? | Masqueraded as a security program module | Masqueraded as a security program module and used normal certificates. |

| October 2015 | ? | HWPx vulnerability (CVE-2015-6585) | Masqueraded as a resume of a person with experience working with the military. |

| October-November 2015 | Defence industry (ADEX participating companies) | HWPx vulnerability (CVE-2015-6585) | Masqueraded as promotional document for a national defence seminar. |

Table 4: List of Operation Red Dot attacks (2014–2015).

In March 2015, an installer was discovered that was designed to infect systems and that masqueraded as a security program used by political institutions.

| SHA256 | MD5 |

| b79faac94bde8481aea8ebd97fb506bdc6964105853b9a9f8523d7aad699e649 | 82e195bc7302e8b64aedf48af889a376 |

| b6d540571b2cb58057631a108ecef2bba56251530565f380044f8359f7abaf40 | 0a93ccec3824569f7bc55c520de4fc4f |

| ecddd99fe084e01213edefb4dbc1d683d8ad88d832de34279615b231bce022b5 | ae44cb4b42debf7507313cfa56f1158d |

While the intended target of this malware is not known, it is highly likely to be the users of the security program in question: various public and defence institutions.

Escad B type, known as Duuzer, was discovered in April 2015 following its attack on the defence industry and diplomatic institutions.

The attacks on political institutions have continued since then. This variant uses the method of sending an executable file disguised as a document file instead of exploiting a vulnerability. The code of this variant is very similar to the code used in the Sony Pictures hack.

In September 2015, malware masquerading as a security module was distributed (5831e614d79f3259fd48cfd5cd3c7e8e2c00491107d2c7d327970945afcb577d_fa6ee9e969df5ca4524daa77c172a1a7).

At the same time, a zero-day attack began which exploited a Hangul World Processor (HWP) vulnerability (CVE-2015-6585).

The South Korean media is often filled with news reports of attacks similar to the November 2014 Sony Pictures hack that are still active in Korea [10].

In October 2015, malware masquerading as a personal resume was discovered (794b5e8e98e3f0c436515d37212621486f23b57a2c945c189594c5bf88821228_1c67fb74d778c3ce15ac4890276f892f). The intended target of this attack is likely to be in the military as the work experience that was listed on the resume was mainly related to the military and North Korea.

The attack on the defence industry that took place in the same month was a spear-phishing attack which impersonated the Korean Society for Aeronautical and Space Sciences (KSAS).

In this attack, emails were sent to targeted recipients with malicious attachments. When the recipients opened the attachment, which was disguised as an invitation (초청장.hwp), it used the HWP vulnerability (CVE-2015-6585) to install a backdoor on the recipient's computer (c5be570095471bef850282c5aaf9772f5baa23c633fe8612df41f6d1ebe4b565_02b5964f93bcd22c4f6cedd64c3b3de3).

In November 2015, an attack was made on the Seoul International Aerospace and Defense Exhibition (ADEX) participants using a malicious email entitled 'Top 10 Weapons Exhibited at the Seoul Air Show'. When the recipient opened the disguised attachment (33e99f86d1c94c2798ee1ded42d513824cbd487994691369b1b9b781ebda3947 _660b607e74c41b032a63e3af8f32e9f5), malware exploiting the HWP vulnerability was executed to infect the computer with Escad (ce0e43c2b9cb130cd36f1bc5897db2960d310c6e3382e81abfa9a3f2e3b781d7_5df43b35c806c0a47ce379feaf715ee7).

The National Intelligence Service of Korea later revealed that a member of the National Assembly and their staff had been targeted by an attack which led to the leakage of governmental audit materials [11].

Redobot, an early version of Escad, is known to have been in the wild between April 2011 and April 2014. There are many differences between the early version and the newer variants of the malware that have been discovered since 2014. In March 2014, the first variant of the Escad DLL type was discovered. It continued to be active until March 2015.

The variants of Escad are mainly classified into types A, B and C.

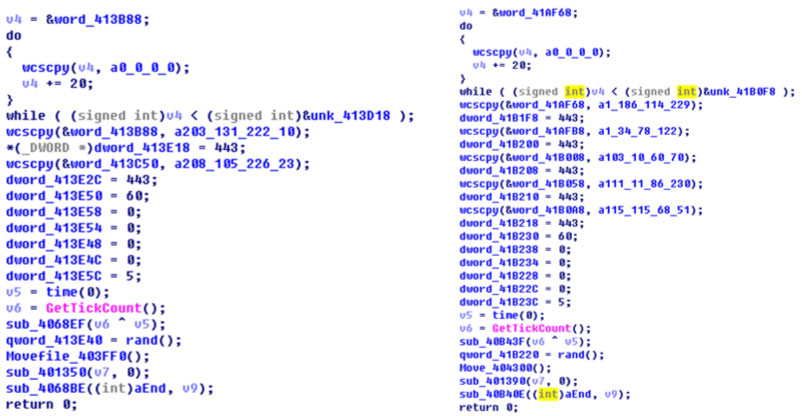

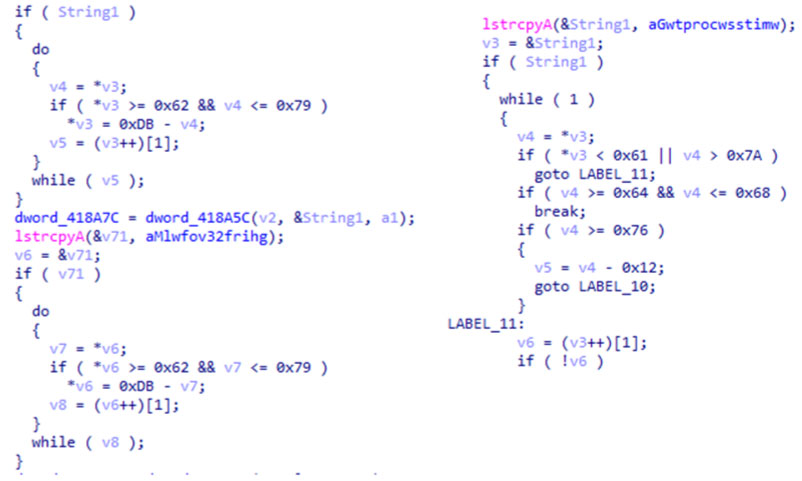

Type A is the malware that was used to attack Sony Pictures and was first discovered in July 2014. It was used in attacks on political institutions in South Korea until April 2015. The characteristics of type A are that two IP addresses are set up in the main code, the name of the DLL file uses XOR 0xA7 encryption, and the string of the logging API is obfuscated with spaces and dots (.). Figure 4 shows a comparison of samples used in the South Korea attacks and the Sony Pictures hack.

Figure 4: Comparison of samples used in the South Korea attacks and the Sony Pictures hack.

Figure 4: Comparison of samples used in the South Korea attacks and the Sony Pictures hack.

Like type A, type B (which is called Duuzer) sets up two IP addresses in the main code, but the format of the code has changed. It does not obfuscate the API address but uses the XOR command to request the encrypted DLL name and API to use.

Type C operates as a service and also sets up two IP addresses in the main code, just like types A and B. It uses its own decode routine to extract the DLL name, API and a backdoor command. Here, the code for the backdoor is identical to type A.

When compared with the malware discovered up to 2015, the variants discovered since 2016 show many differences in code and use new techniques to get around security programs.

Examples of some of the major attacks are shown in Table 5.

| Date | Target | Method | Description |

| Sept 2015 | Defence contractor | HWP vulnerability | An attack using an HWP vulnerability. Dropped the loader. |

| Nov 2015 | Conglomerate | ? | Loaded malware from an encrypted igfxsrvks.lrc file. |

| July 2016 | Shopping mall | Spear phishing | Attacked a shopping mall worker using a family photo in May 2016. |

| Oct 2016 | ICT | ? | An attack using the OpenType Font (CVE-2016-7256) vulnerability. |

| Oct 2016 | Conglomerate | ? | Discovered a loader in resources section that contains malware and reads encrypted files. |

| Nov 2016 | Conglomerate | ? | A loader with a huge file length. |

| Feb 2017 | Financial institution | ? | Attacked the vulnerability of logical network separation software. |

| Aug 2017 | Conglomerate | ? | Loaded an encrypted igcxsrvrs.lrc file. |

Table 5: List of Operation Big Pond (2015–2017) attacks.

The threat group behind Operation Big Pond attacked not only political institutions and defence contractors, but conglomerates, shopping malls and ICT companies. KrCERT said that, in 2016, this threat group attacked asset management solution developers, hosting companies, academic associations, media, logistics information service providers, etc. It attacked a financial institution using the vulnerability of network separation software in February 2017, and constantly attacked cryptocurrency exchanges throughout 2017.

The threat group used a zero-day vulnerability in its attack: AhnLab and KrCERT discovered the Open Type Font (CVE‑2016-7256) vulnerability and reported it to Microsoft in autumn 2016 [12]. The attacker had started to make attacks on this vulnerability in the summer of 2015, and these attacks went undiscovered for more than a year. According to KrCERT, the Script Engine Memory Corruption (CVE-2016-0189) vulnerability was also used in the attack.

The threat group used a few techniques to bypass security programs, such as 'loading' (generating malware of tens of megabytes in size and executing a file only within memory, without dropping it). The group understood that some security programs do not scan or perform behaviour analysis on files of huge sizes and thus increased the size of the malware file and executed the code only in memory (without creating an execution file) to avoid detection.

In the case of msnconf.exe (7807568335687dd7f707cadd7a7c8e7d79082f15c07d263230ed90bf601bfcc6_250115ddbbc54207825855b60049f75f), once the file is executed, a DLL file with random name is created, empty data is repeatedly added to the end of the file, and the size of the file is increased by 67,229,889 bytes (62439a4a5eb9c6b2c6559928481b3f2bad5c753c297b2f55e2642751a10ca654_ fa73530df2d2cec5e591a9d666fccfa2). Once the DLL file is executed, the encrypted code is unpacked into the memory and executed.

The malware in the form of a loader was first discovered in 2015, and was used at full-scale in 2016. There are two types of loaders: one that hides the actual malicious code (mainly the backdoor) in the encrypted area inside the malware, such as the resource section, and executes in the memory; and one that executes the malware inside the memory by reading the external encrypted file. In the case of an encrypted file, sometimes the specific function of the malware cannot be identified, because no encrypted data file is identified. Some loaders are huge in length – sometimes more than 50 megabytes.

This threat group has been attacking cryptocurrency exchanges and research institutions since 2017. It posed as government authorities and disguised its malware with file names relating to tax audit requirements, criminal investigations, etc.

| Filename | English translation |

| (대검)2017임시113호 (마약류 매매대금 수익자 추정 지갑주소 164건).hwp | (Prosecutor) 2017Temp. 113 (164 addresses of wallets of criminals).hwp |

| [붙임]조사 당일 구비하여야 할 서류 1부.hwp | [Attachment]documents to be submitted on the day of hearing.hwp |

| 국내 가상화폐의 유형별 현황 및 향후 전망.hwp | Trend of cryptocurrencies in Korea.hwp |

| 나의 직장에 대한 생산성 향상을 위한 개선해야 할 문제점과 개선 방안.hwp | Issues on improving productivity at work.hwp |

| 내부포털시스템 요구사항.hwp | Requirements for internal portal system.hwp |

| 로그인 오류.hwp | Login errors.hwp |

| 美 사이버 보안시장의 현재와 미래.hwp | US cyber security market trend.hwp |

| 법인(개인)혐의거래보고내역.hwp | Suspected transactions.hwp |

| 불균형한 관계의 유대와 인지적 부조화를 내포한 관계의 유대가 종업원의 성과에 미치는 영향에 관한 연구.hwp | Study on impact of unbalanced relationship and recognition on performance of employees.hwp |

| 비트코인_지갑주소_및_거래번호.hwp | Bitcoin wallet addresses and transaction no.hwp |

| 새로운 패밀리 랜섬웨어.hwp | New family ransomware.hwp |

| 세무조사준비서류.hwp | Docs for tax audit.hwp |

| 스타트업 투자 시장 활성화 방안.hwp | Startup investment promotion plan.hwp |

| 양식1.hwp | Form1.hwp |

| 전산 및 비전산 자료 보존요청서.hwp | Data preservation request.hwp |

| 전자금융거래법 일부개정법률안.hwp | Partial amendment proposal for Online Financial Transaction Act.hwp |

| 조직의 소금같은 존재인 ‘투명인간’에 주목하라.hwp | Focus on the ‘invisible man’ who you must have in your organization.hwp |

| 환전_해외송금_한도_및_제출서류3.hwp | Money transfer limits and forms3.hwp |

Table 6: Names of files used for attacks.

Hangul by Hancom is the most widely used word processing software in Korea and supports EPS (Enhanced PostScript), an Adobe image processing script. When there is an EPS in a Hangul file, the script is automatically executed when the document is opened, without any notice to users. The vulnerability that uses EPS (CVE-2015-2545) was discovered in 2015, and the malicious HWP document exploiting this vulnerability first appeared in September 2016. The vulnerability was still actively exploited as of July 2018. The EPS created by this group is noticeably different from the script codes of other threat groups active in Korea.

The most recently updated version of Hangul by Hancom does not allow the malicious script written in EPS be executed. However, since no new vulnerability in Hangul by Hancom has been found, it seems that the attack using this vulnerability will continue. Thus, it is important for users to apply the most recent security update in order to avoid the EPS script attack.

Although they are somewhat different from the malware codes used to attack Sony Pictures, there are other examples of malware related to the Lazarus Group.

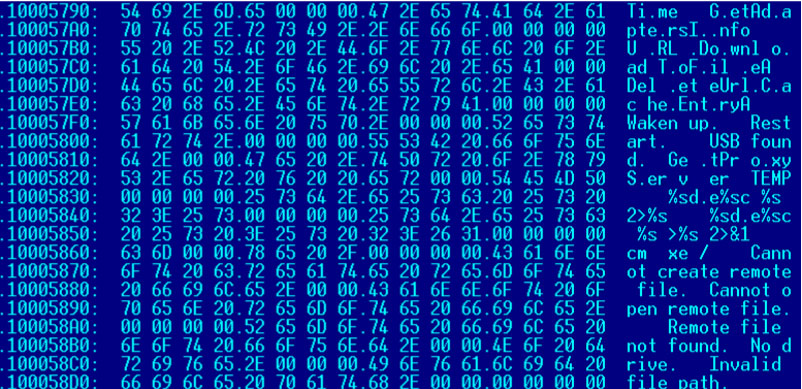

Navepry is known to be one of the pieces of malware created by Lazarus Group. It was first discovered in 2012, and has been seen in large volumes since 2014. This malware mixes the order of text strings of API addresses. Figure 5 shows the obfuscated strings.

Figure 5: Obfuscated strings.

Figure 5: Obfuscated strings.

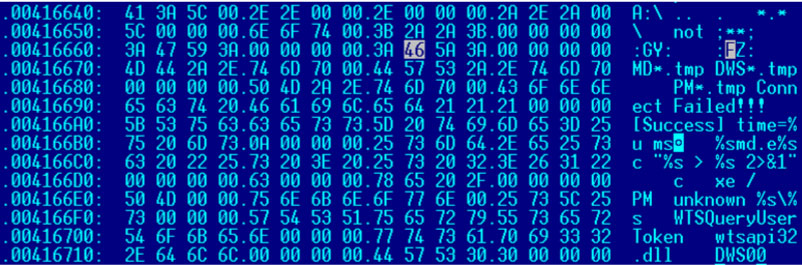

This malware contains text strings such as 'GY' and 'FZ', and executes the cmd.exe file in a unique way. Figure 6 shows the unique text string of Navepry.

Figure 6: Unique text string of Navepry.

Figure 6: Unique text string of Navepry.

This malware was used to attack political institutions, defence contractors and large Korean companies.

| Date | Target | Method | Description |

| March 2015 | ? | Disguised as an installer | Installation version of a security program used by political institutions. |

| April 2015 | Defence contractor | Exe file disguised as a HWP file | |

| April 2015 | Conglomerate | ? | Disguised as an instant messenger. |

Table 7: List of Navepry attacks.

These codes mix up the order of API characters to make it impossible to read, and there are a few methods for doing so.

Figure 7: Compare obfuscation codes of Navepry.

Figure 7: Compare obfuscation codes of Navepry.

There are many differences between this malware and the Escad variants, but some mutations are similar to the existing Escad. This malware was discovered either alone or together with backdoors (such as Escad) on the systems of targets of the Lazarus Group. The malware seems to be being used by the same group, because the attacker sometimes used the Open Type Font vulnerability.

The Lazarus Group can largely be divided into two separate groups: the one that focused on attacking the Korean military in 2008 and another that emerged via the 7.7 DDoS attack (Dozer) in 2009. Many reports on the Lazarus Group do not distinguish the two from one another. The exact number of individuals involved with the Lazarus Group is unknown, however, their new and variant attack method, which was used in the attack on the Seoul ADEX 2015 conference, suggests that they may now have more than two groups operating independently.

Initially, there was a clear connection between the two groups. Redobot dropper (37be47f8df3c94d365d693855d1af5ac8b94eedd1b3b3122586a6d48611230bb_49ace8a624dd22f3110f041a324d1646), discovered in 2011, contains a 'BMZA' text string.

The 'BM' text string was used in a malware attack on targets in the defence field in 2009 and 'BM6W' was also used in the 6.25 Cyber Terror(KorHigh) that took place on 25 June 2013. 'BM' is also used by Bmdoor, malware that was used in Operation Black Mine in 2014. The exact meaning of BM has not yet been identified. However, it is constantly included in the malware as if it is some form of signature used by its creators.

The malware used in the Sony Pictures hack also includes a unique cmd.exe command, which similarly remains a mystery.

This threat group used various infiltration methods, such as spear phishing, watering hole attacks, webshell uploads, etc. to take over the computing networks of political institutions, defence contractors and large companies in 2014; defence contractors and major companies in 2015; and hosting companies and media companies in 2016. Since 2017 the attacks have been concentrated onto cryptocurrency exchanges.

This threat group used zero-day vulnerabilities such as the VBScript vulnerability (CVE-2016-0189) and Open Type Font vulnerability (CVE-2016-7256) and attempts to bypass security programs using a loader that has a huge file size and by executing only in memory.

Pieces of malware that are similar to that used to hack into Sony Pictures are still being discovered. Now, this threat group is attacking targets not only in Korea, but also in other parts of the world. Many researchers are tracing and analysing this group. However, the malware used to hack Sony Pictures became so famous, that it would be easy for anyone to imitate it. When studying the relationship (of attacks) one must be fully aware of this fact.

Security experts around the world must work together to trace and study this threat group, which is active in all corners of the world.

[1] Sayer, P. Malware attacks on two banks have links with 2014 Sony Pictures hack. CSO. https://www.csoonline.com/article/3069502/data-breach/malware-attacks-on-two-banks-have-links-with-2014-sony-pictures-hack.html.

[2] https://www.thaicert.or.th/alerts/admin/2018/al2018ad001.html.

[3] Sherstobitoff, R. Analyzing Operation GhostSecret: Attack Seeks to Steal Data Worldwide. McAfee. https://securingtomorrow.mcafee.com/mcafee-labs/analyzing-operation-ghostsecret-attack-seeks-to-steal-data-worldwide/.

[4] Hesseldahl, A. Sony Pictures Investigates North Korea Link In Hack Attack. Recode. https://www.recode.net/2014/11/28/11633356/sony-pictures-investigates-north-korea-link-in-hack-attack.

[5] Corera, G. UK TV drama about North Korea hit by cyber-attack. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-41640976.

[6] Alert (TA14-353A). US-CERT. https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/alerts/TA14-353A.

[7] Operation BlockBuster. https://www.operationblockbuster.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Operation-Blockbuster-Report.pdf.

[8] Fagerland, S. From Seoul To Sony: The History of the DarkSeoul Group and the Sony Intrusion Malware Destover. https://github.com/kbandla/APTnotes/issues/260.

[9] WannaCry: Ransomware attacks show strong links to Lazarus group. Symantec Official Blog. https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/wannacry-ransomware-attacks-show-strong-links-lazarus-group.

[10] http://www.etnews.com/20151007000172.

[11] http://news.joins.com/article/18899410.

[12] Hardening Windows 10 with zero-day exploit mitigations. Microsoft Secure. https://cloudblogs.microsoft.com/microsoftsecure/2017/01/13/hardening-windows-10-with-zero-day-exploit-mitigations/.

[13] 사이버 침해사고 정보공유 세미나 자료집 2016년 4분기 (Analysis of recent APT attack and infringement cases 4Q 2016). KrCERT. https://www.boho.or.kr/data/reportView.do?bulletin_writing_sequence=25246.

[14] Park, S. Anatomy of attacks aimed at financial sector by the Lazarus group. https://www.slideshare.net/SeongsuPark8/area41-anatomy-of-attacks-aimed-at-financial-sector-by-the-lazarus-group-104315358/1.

[15] Jo H.; Lee, H.-J. Deep dive analysis of HWP malware targeting cryptocurrency exchange.