ESET, Czech Republic

Copyright © 2017 Virus Bulletin

With the ever-increasing use of banking-related services on the web, browsers have naturally drawn the attention of malware authors. They are interested in adjusting the behaviour of the browsers for their purposes, namely intercepting the content of web forms, modifying server responses manifested as webinjects, and confirming validity of spoofed SSL certificates. These goals are usually achieved by placing malicious code at certain addresses within a browser process.

It has been more than seven years now since the infamous Zeus bot first successfully took advantage of Mozilla Firefox by hooking specific exported functions, and the same approach has been widely used by others ever since. Moving to Microsoft Edge, the browser's developers have made their best efforts to mitigate arbitrary code execution, using technologies like Code Integrity Guard (CIG) and Arbitrary Code Guard (ACG), but the focus is on stopping exploitation of the browser itself, rather than preventing execution of injected code delivered by a remote malicious process. Finally, cybercrooks seem to have the greatest trouble adapting their hooks in Google Chrome. Though it might not have been the primary intent of the developers, the custom implementation of its SSL functionality has resulted in a cat-and-mouse game thanks to the fact that the attack points are unexported and change regularly.

In our presentation we will guide the audience through an overview of the techniques used by major banking trojans in the wild. We are pleased to see that the ease of implementing hijacking methods is diminishing, and that attackers are under constant pressure to adopt changes. Moreover, security solutions offer various browser protections that work very well against existing methods. How do they handle that? Wouldn't it be great to see the mitigation in the first possible layer? We consider this as a topic for discussion. As a side result, we also transform our collected knowledge into a plug-in for the Volatility Framework that extends the functionality of apihooks within the scope of browsers.

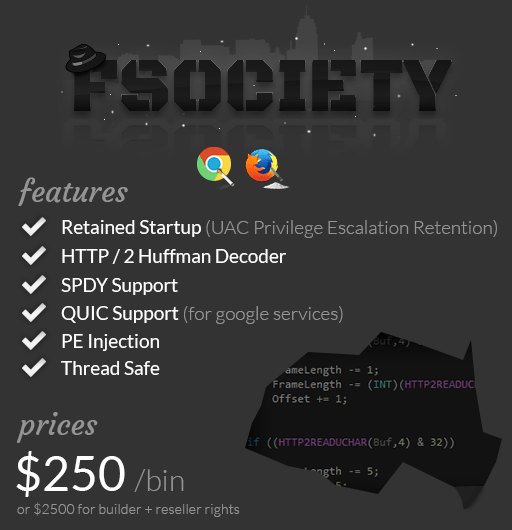

The history of man-in-the-browser (MITB) attacks goes back at least as far as 2007, to the birth of the Zeus bot. The basic principles of MITB, including both form grabbing and webinjects, their hooking techniques and their role in the cyber-underground economy, are widely known and understood [1, 2]. Attack trends have evolved hand-in-hand with the development of web browsers and network protocols. Nowadays, a robust banking trojan cannot exist without code injects of both 32-bit and 64-architectures, or without the ability to put the HTTP/2 protocol [3] out of action. The dark web is full of advertisements for malware promising fancy features that would lead to a large botnet, but their authenticity is questionable and their perceived reputation depends on the advertiser. In Figure 1 we show an example of a relatively recent, unverified, offer from October 2016.

Figure 1: Advertisement for an advanced banking trojan.

Figure 1: Advertisement for an advanced banking trojan.

The key principle in MITB is to hijack a browser's features for the benefit of the attacker. This is realized predominantly through malicious handlers installed to address specific functions in the browser's process space. The methods used to install the hooks generally do not need to be modified over time; however, there is one group of exceptions which has increasing dominance: Chromium-based projects. The contribution of this paper is to summarize the technical details of how malware developers reach their goals despite the raising of the bar in terms of defensive measures. During our research, we recognized well-written coding of a professional standard, as well as a series of faux pas ranging from redundant checks of conditions to illogical code flow.

There are five major web browsers in widespread use on Windows systems: Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer, Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome and Opera. For an attacker, the ease of adapting the desired function hooks differs with each browser. While the attack points in the Firefox and Microsoft browsers are exported, and therefore easily hooked, the situation in Chrome and Opera is different. Both of these programs are based on the common codebase of the Chromium project, which implements SSL functionality in a customized form.

There are multiple obstacles that malware authors have to overcome before they can achieve their goals:

Malware authors vary in the way they implement attacks, displaying different levels of code quality and optimization, however they are quite far from being cargo cult programmers.

Apart from hooking the attack points, malware developers are also interested in turning off special protocol features like HTTP/2, SPDY and QUIC as they are implemented in browsers. The attackers really don't enjoy these protocols because request and response HTTP headers are compressed, and therefore harder to parse. Instead of implementing complicated routines to extract the content, they apparently prefer to disable the use of these protocols in the way in which each browser is configured.

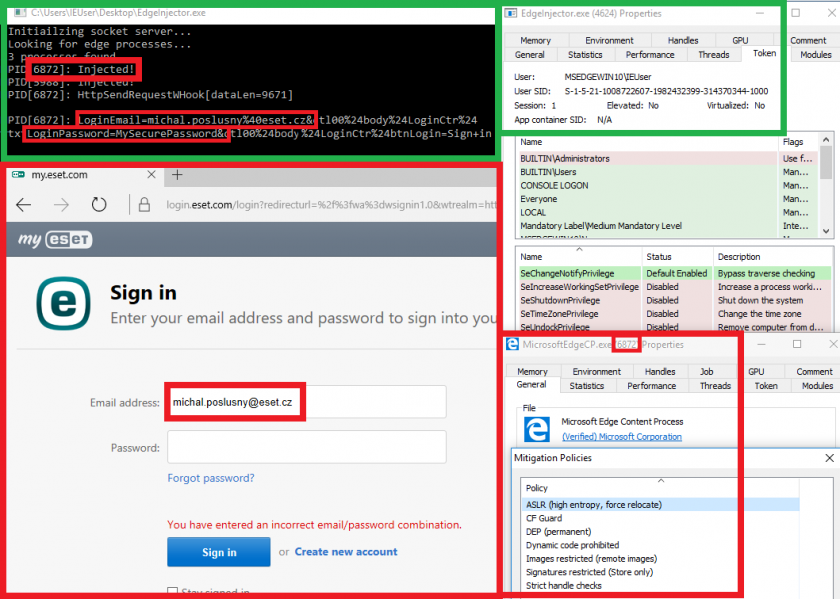

Microsoft Edge is implemented only as a 64-bit web browser. Injection is possible, even though the browser runs under the supposedly safe Runtime Broker process like the apps from the Windows Store. In view of Microsoft's newly introduced dynamic code mitigation techniques, which include disallowing allocation of new executable memory pages and not allowing existing code pages to be made writable once a process is initialized [4], we had the impression that injection cannot be realized easily. However, the opposite is true: we were able to inject a payload into the Edge browser just as we could into any other process. Only medium integrity level without special privileges was needed to accomplish that. Figure 2 shows our custom command-line tool, which injects its code into all instances of Edge, hooks the attack points and exfiltrates login data.

Figure 2: Hijacking network traffic in Microsoft Edge.

Figure 2: Hijacking network traffic in Microsoft Edge.

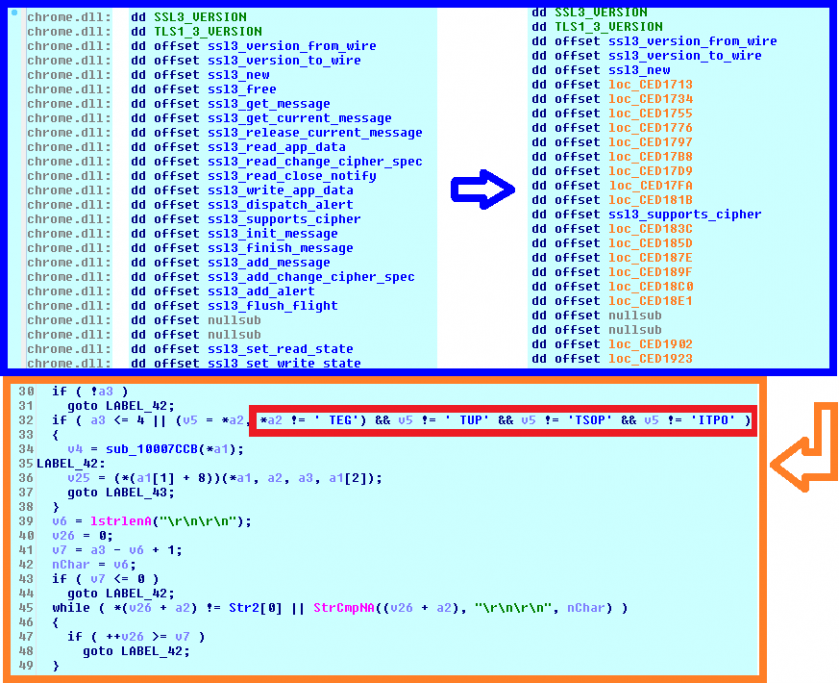

Because these Chromium-based browsers do not export the attack points, malware authors have been forced to come up with various methods of locating them manually. Most malware families have their own unique approach, even though they could copy from each other or from various source code leaks. While MITB support for Chrome is a must due to its market share, support for Opera is rare. The attack points are usually obtained by locating Chrome's SSL virtual method table, defined as the SSL_PROTOCOL_METHOD structure (which we denote subsequently as SSL VMT), which contains functions that send and receive unencrypted HTTP(S) data (ssl3_write_app_data and ssl3_read_app_data, respectively; ssl3_free is additionally hooked; cf. the upper left frame of Figure 6). Note that Chrome switched to the BoringSSL implementation with Chrome 41 (March 2015), as the previous Mozilla Network Security Service (NSS) was dropped. Opera switched to Chromium's codebase and updated its releases accordingly, starting with version 15 in July 2013. Opera has incorporated BoringSSL code since Opera 28, released in March 2015.

Now we provide a catalogue of hijacking techniques as implemented by contemporary banking trojans active in the last year. Despite our attempts to include as many families as possible, the list is most likely incomplete. This is because we may have overlooked projects that are not prevalent enough to be easily spotted, projects that were in the testing phase when banking modules could not be acquired because a control server was not yet accessible, the resurgence of older variants, or malware omitting its banking module in newer versions. When referring to malware families, we use ESET's detection convention with a prefix 'Win/' if we mean both 32-bit and 64-bit variants. These names may easily be cross-referenced on VirusTotal, nevertheless we mention the most commonly known alternative in parentheses. If the names are identical, we will omit the prefix.

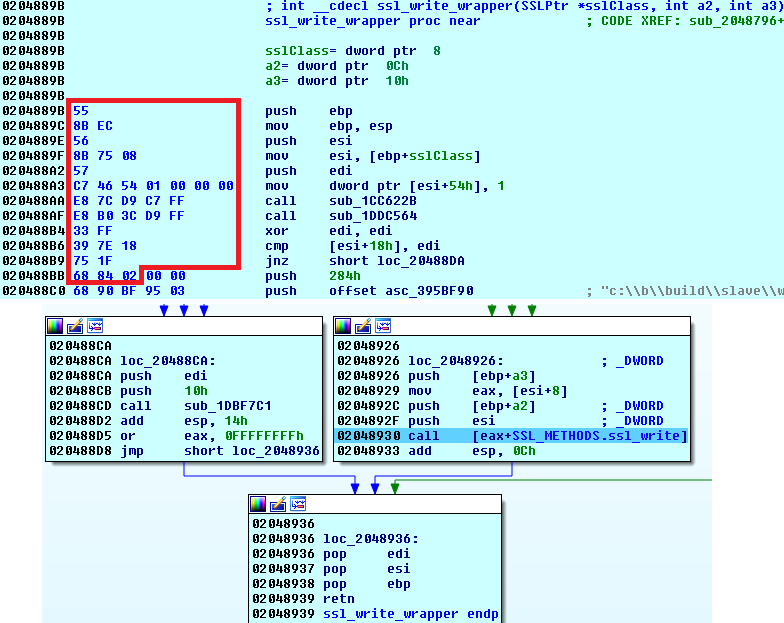

The families that we considered already to be eradicated due to the author's retirement or actions on the part of law enforcement agencies include Win32/Tinba, Win32/Battdil (a.k.a. Dyre) [5], Win32/Corebot [6] and Win32/Phase (a.k.a. PhaseBot, previously developed as Win32/Napolar, a.k.a. SolarBot). We did not see a banking module in the latest versions of the Win32/Emotet malware, either [7]. Also, our focus is not on families that prefer the man-in-the-middle attacks, which are typical of many Win/Zbot (a.k.a. Zeus) [8]. However, we found a fork of Zeus known as Floki [9, 10] trying to include MITB in October 2016. Looking at its approach to MITB for Chrome, the bot had two hard-coded byte sequences, which served for pattern searches in a mapped chrome.dll. The match was successful for all Chrome 52 major versions. The patterns were not designed to hit the corresponding attack points in SSL VMT but their wrappers instead (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Pattern search for Floki attack points.

Figure 3: Pattern search for Floki attack points.

Interestingly, there was a sample of Win32/PSW.Papras.CU from 2013 (known as an early version of Vawtrak) that demonstrated that its authors didn't know at that time how to handle hooking in the newly introduced Chrome browser, and they disabled any network functionality in a Chrome process instead. This was done by calling the WSACleanup() routine in an endless loop. The victim was then forced to switch to another browser, most likely Internet Explorer, which was installed by default on every Windows system, and since it was the most prevalent browser at the time, it's natural to expect that the authors already had hooks for IE ready (and indeed they did).

The Dridex bot is one of the most adaptable and prevalent in-the-wild banking trojans. The authors update the bot's code consistently and the botnets are still very active despite several botnet takedowns and arrests relating to this group [11, 12].

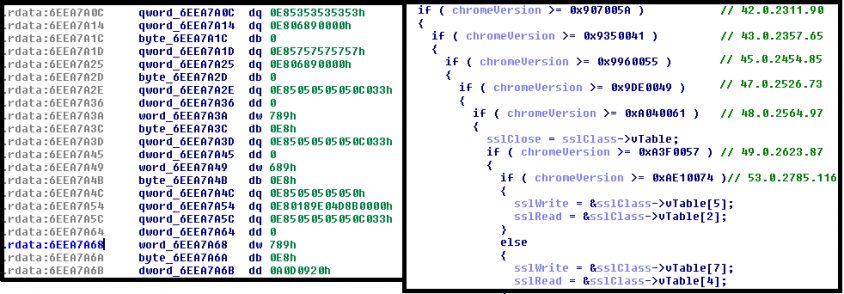

The way Dridex locates the attack points in Chrome is heavily dependent on the browser version. Rather than relying on a generic solution, Dridex seems to rely on a prompt response from its authors, who usually take up to a few days at most to update their banking module to cover a new release of Chrome, cf. Table 1. The trojan looks up Chrome's version in the associated Uninstall registry key. This seems not to be an optimal strategy as the portable versions do not provide this information – we have observed more reliable methods implemented by competing banking trojans, such as extracting the version from chrome.dll's module handle or resources. Nevertheless, the version is then used to decide which pattern will be used to find the SSL VMT. In the past, Dridex used patterns locating specific parts of code in the .text section that contained a static pointer to SSL VMT. In the left frame of Figure 4, we show a list of patterns that helped identify a specific position in the .text section of chrome.dll. The list has grown as each major release of Chrome produces slightly different code. Moreover, there were many changes of indices of the desired attack points in the table, so the bot had to resolve them case by case, as shown in the frame on the right.

Figure 4: Pattern search and version checks of Chrome by Dridex.

Figure 4: Pattern search and version checks of Chrome by Dridex.

In the most recent releases of Dridex, the authors have finally dropped locating the static pointer, and instead they look for the SSL VMT directly in the .rdata section using the \x03\x04\x03 pattern. This is a substring of a concatenation of two constants signalling the highest and the lowest versions of SSL supported by the methods in SSL VMT.

As Table 1 shows, successful adaptation addressing changes in SSL VMT for the latest Chrome version was usually achieved in just a few days. The third column shows the lowest version number of the bot collected by ESET LiveGrid that successfully implemented the attacks for the latest stable Chrome release. In other words, we have not caught any bot with an earlier build number that managed to attack the corresponding release successfully. The timestamp in the PE header can easily be altered; however, in these cases the values in the fourth column seem to be the original values, since they correspond well with the release dates of Chrome versions.

| Chrome stable version | Release date (DD/MM/YY) | Dridex version | Timestamp (DD/MM/YY) |

| 40.0.2214.115 | 19/02/15 | 2.093 | 11/03/15 |

| 42.0.2311.90 | 14/04/15 | 2.108 | 17/04/15 |

| 43.0.2357.65 | 19/05/15 | 3.011 | 26/05/15 |

| 44.0.2403.89 | 21/07/15 | 3.073 | 06/08/15 |

| 45.0.2454.85 | 01/09/15 | 3.102 | 25/09/15 |

| 47.0.2526.73 | 01/12/15 | 3.154 | 07/12/15 |

| 48.0.2564.97 | 27/01/16 | 3.167 | 29/01/16 |

| 49.0.2623.87 | 08/03/16 | 3.188 | 10/03/16 |

| 51.0.2704.106 | 23/06/16 | 3.225 | 24/06/16 |

| 53.0.2785.116 | 14/09/16 | 3.258 | 26/09/16 |

| 54.0.2840.71 | 20/10/16 | 3.269 | 17/11/16 |

| 58.0.3029.81 | 19/04/17 | 4.048 | 16/05/17 |

Table 1: Reaction times of Dridex.

Unlike Dridex, which seems to have been developed by a single development team with the same binaries shared across all campaigns/botnets, Win/Spy.Ursnif has several unrelated forks of a common code base that evolved over time and are, these days, quite different from each other in many aspects. The source code of the project, originally called ISFB and referring to version 2.13.24.1 build 459, was leaked in late 2015 and is still available on GitHub. Since then, many forks of the project have come into being, for example Dreambot, IAP, Powersnif, GozNym, etc. [13].

The Chrome version is determined by looking up the version info directly in the chrome.exe binary, which is probably the most reliable way.

This fork also has a very interesting SSL VMT lookup – probably the most advanced we have seen. It walks through the relocations present in the .rdata section and hooks every virtual method it can find with a common handler. Every time the handler is called, it looks for 'GET', 'POST', 'PUT' or 'OPTI' strings in the third argument on the stack (cf. Figure 5). If any of these four strings is found, it will assume it has found the ssl3_write_app_data function in SSL VMT, and it counts the position of the other two attack points and hooks them with new, specific SSL handlers. The relative offset of the table, together with the checksum of chrome.dll, are automatically saved into the registry, so it doesn't have to do this 'nasty' thing again. The next time it is injected into Chrome, it can hook the SSL VMT directly. A custom exception handler is also installed in order to avoid ACCESS_VIOLATION crashes when dereferencing an argument that is not a pointer. This increases stability during these unstable actions.

Figure 5: Almost every Chrome virtual method is initially hooked by IFSB.

Figure 5: Almost every Chrome virtual method is initially hooked by IFSB.

MITB attacks against Opera do not seem to be maintained by the IFSB authors. Locating and hooking the attack points would be successful with their robust approach, and we tested this against some older releases. However, the lookup is not even triggered in most Opera versions due to a design change that transferred SSL VMT to a different module. The authors could very easily correct this if they wished to.

The first report of this threat appeared in June 2017 [14]. This fork does not follow the original versioning; in fact it possesses no version info at all. The PE timestamp of the earliest acquired sample reads 12/12/16. The threat mostly targets countries like Mexico, Colombia and Chile. The family can be identified by the PDB strings:

The developers clearly didn't participate in any festivities on Saint Nicholas' Day that year, perhaps unlike many of the victims from the predominantly Roman Catholic countries receiving their code. The bot does not bother obtaining the Chrome version, but searches for a series of version-specific patterns instead, hoping that one will succeed. The pattern searches are likely to flag incorrect addresses as the attack points. This is exactly what happened with Chrome 59, which would be hooked correctly using the pattern search for Chrome 58, but due to the bot's illogical traversal from the oldest to the newest releases, it wrongly matched to the place that worked for the old Chrome 53 so the hooks were installed on a completely different virtual method table. Moreover, there is also a failure in preserving the attack support from Chrome 57 64-bit to Chrome 58 64-bit because after a successful discovery of SSL VMT, there are unnecessary additional conditions on the first byte in the bodies of functions that remained the same in 32-bit releases, but not in these 64-bit releases. Overlooking all these details seems like either carelessness or erroneous thinking on the part of the malware developers.

An unreferenced character string 'OPERA.exe' suggests the possible withdrawal of the MITB feature for this browser.

Win/Nymaim first incorporated the ISFB functionality directly into a downloadable banking module that was enormously obfuscated soon after using the same techniques as the main Win/Nymaim project cf. [15, 16].

There are clues indicating that this project is a direct successor of Dyre, the banking trojan that was active between March 2014 and November 2015. Moreover, there is an unreferenced specific string, 'K8DFaGYUs83KF05T', which originated in the Carberp source code. The first version that was uploaded to VirusTotal was numbered 1001 with the timestamp 2016-06-22. A detailed analysis is available in [17].

TrickBot queries the Software\Google\Chrome\BLBeacon registry key to obtain the Chrome version and searches for the \x03\x04\x03 pattern to locate SSL VMT. Being a relatively recent project, it does not support legacy versions prior to Chrome 54.

This threat is under constant development, evolving from the early v1.0.2.3 in December 2013 [18] up to the current v3.0.0.1, with major version 3 first reported in September 2016 [19]. The main module is heavily obfuscated, as are the plug-ins, and data is mostly stored in a variety of structure types, which slows down the analysis.

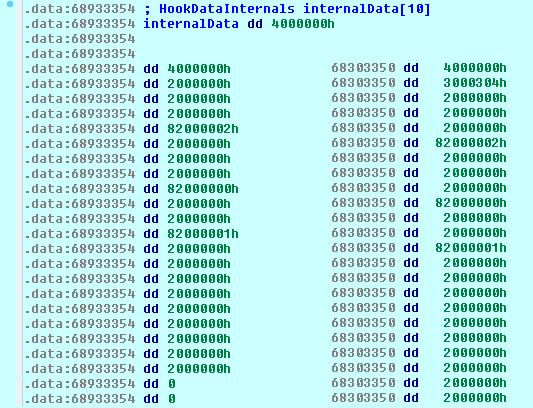

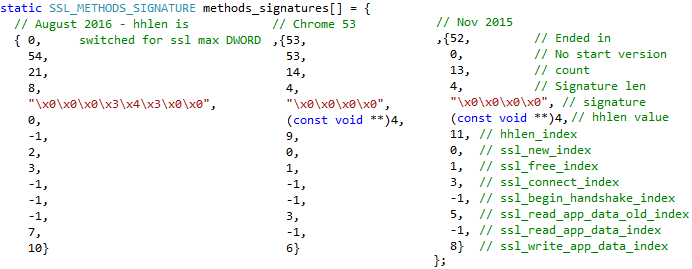

As is the case with Win/Spy.Ursnif, Qadars parses relocations to obtain candidates for SSL VMT located in the .rdata section. Every selected virtual method table is then compared against a list of masks, which are basically structures of four-byte bitfields. There are 10 masks of that form in total, two of which are displayed in Figure 6. The upper byte generally orders a condition evaluation, such as whether the element in the table is equal to 0x304, or whether the element is a function from the .text section, or if it also points to 0, and so on. If the table is SSL VMT, then the position of entries with the upper byte equal to 0x82 identifies the indices of the three attack points and the lower byte then indicates its internal position. Qadars tries every mask in the array from newest to oldest until it succeeds.

Figure 6: Structure of masks present in Qadars.

Figure 6: Structure of masks present in Qadars.

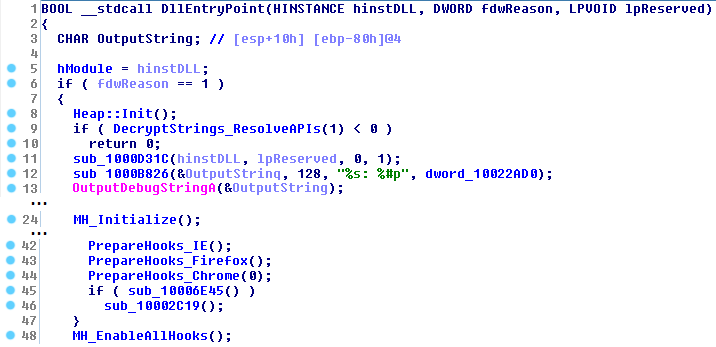

Qbot has been known for as long as Zeus, but it is still active. A detailed description is provided in [20, 21]. The bot doesn't care into which browser it is currently injected; it simply tries to hook all the potential points of attack that it can find in its process space (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Hooks are prepared by Win/Qbot for every browser, regardless of the process name.

Figure 7: Hooks are prepared by Win/Qbot for every browser, regardless of the process name.

Hooking is done in two stages: first, Qbot finds the functions it wants to hook, stores all the necessary information and creates a trampoline to the original function [22]. In the second stage, all the previously stored functions are hooked at once.

When looking for Chrome's attack points, Qbot doesn't try to hook SSL VMT directly, but searches for higher level wrappers in the code section. They are found using very specific patterns that are crafted for every version of Chrome, as these functions change frequently and the patterns usually do not last longer than one major release. Qbot loops through all stored patterns from newest to oldest until the valid attack points are found.

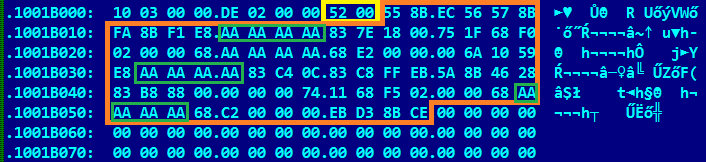

While Qbot doesn't really puzzle over what process it's residing in, it's very careful and precise when it comes to hooking itself. Qbot uses the 'MinHook' open source hooking library that can be found online. The same hooking library was also used in the leaked TinyNuke source code. However, the structure of patterns is completely different. The structure starts with the word representing the length of the pattern that follows afterwards. The byte 0xAA serves as a wildcard (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Structure of patterns present in Qbot.

Figure 8: Structure of patterns present in Qbot.

There is a really interesting story behind this project [23]. It seems to have been developed by an adolescent French guy who released his code on GitHub under his real name, together with a contact email on a domain established by his father. First, he excitedly shared his project with acquaintances who, unsurprisingly, tried to profit from his concept. He considered this attitude unfair, so he intentionally made the sources available for free, to the disadvantage of other cybercrooks trying to sell his creation on the dark web [24]. Meanwhile, the project was sold on cybercrime forums under various nicknames, all of which were banned for violating the specific rules of the cybercrime market.

There is insufficient evidence that this malware family has spread widely yet. However, there are signs of its initial distribution in the wild, and with many new forks (around 170 at the time of writing) in a mirrored repository on GitHub, its potential to become prevalent is clear.

The structure related to hooking the attack points was copied from an official project supported by Google (called 'Webtestpage' hosted under the profile 'WPO Foundation'), which was available on GitHub. The structure of patterns seems original, because other families use a different design (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Structure of patterns present in Win/Tinukebot.

Figure 9: Structure of patterns present in Win/Tinukebot.

There is also a shift in the method of SSL VMT hooking. The attack points are not replaced in the table itself, but the hooks are installed in the prologues of the desired functions instead. This has a similar impact on detection by the Volatility Framework as in the case of Win/Qbot, because the original apihooks plug-in [25] scans modifications only for exported functions – we were therefore forced to extend its scope.

Table 2 shows the families considered here and their support for MITB attacks against various types of web browser. The second column indicates the latest build of the related bot specified among the families in the first column, as of 6 June 2017. The other columns show the targeted browsers. Note that it's only necessary to specify the browser version for Chrome and Opera. The support of attacks on their releases is enumerated for the latest version of the bot only. However, the code clean-up is also standard practice in these malware projects, so the support for various releases was present in previous bot versions. For instance, Dridex has supported attacks on Chrome since version 40 and perhaps even in earlier versions.

| Banking trojan | Latest version | Web browser | |||||

| IE | Edge (x64) | Firefox | Chrome | Opera | |||

| 32-bit | 64-bit | ||||||

| Win/Dridex | 4.057 (26/05/17) | Yes | No | Yes | 48-59 | 48-59 | No |

| Win/TrickBot | 1025 (22/05/17) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 54-59 | 54-59 | No |

| Win/Spy.Ursnif (Gozi/ISFB) | 2.16 build 943 (09/05/17) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 44-59 | 44-59 | 28;29 |

| Win/Spy.Ursnif.AX | - (26/05/17) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 49-52; 53; 54-58 | 49-52; 53; 54-57 | No |

| Win/Qbot | 0310.734 (24/05/17) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 48-58 | 54-58 | No |

| Win/Qadars | 3.0.0.1 (04/04/17) | Yes | No | Yes | 49-57 | 49-57 | No |

| Win/Tinukebot | - (06/06/17) | Yes | No | Yes | 52; 53; 54-59 | 52; 53; 54-59 | No |

Table 2: Summary of banking trojans’ targets.

The apihooks plug-in works for exported functions only. Therefore, in the case of Microsoft browsers and Firefox, we can use its functionality and just restrict it to browser processes. The harder part is to identify hooks on unexported functions, as is the case with Chrome MITB attacks. As we have shown, there are multiple approaches as to where to put an attacker's handler. Changes of SSL VMT entries are easy to spot as soon as the malware's SSL VMT replacements are completed. The easiest approach to spotting the malicious hook on unexported functions outside of SSL VMT is a pattern search inspired by sequences of bytes found in the analysed families.

The implementation of the plug-in can be found on ESET's GitHub repository [26]. Besides the recognition of hooks in exported functions, the plug-in also supports detecting replacements and hooks in SSL VMT or hooks applied in the wrappers calling functions from SSL VMT. Both architectures have been considered.

The security issues caused by MITB attacks have existed for quite some time. There are several points at which the mitigation of these attacks is possible and several of them have been examined in the past by authors active either in academia or in the anti-virus industry. Most of these approaches focus on webinjects. Buescher et al. reported in their 2011 paper [27] a technology called Banksafe that detects the attempts of illegitimate software to manipulate the browser's network activity. Continella et al. recently designed a system called Prometheus [28], which is able to identify malicious injections, to generate behavioural signatures, and finally to extract target URLs by using the Volatility Framework and YARA rules. In [29], an application layer called HoneyWeb was proposed by Wang to protect institutions from web injection attacks (where web injection scripts are injected into invisible decoy elements).

Let us now discuss possible ways of hardening against a MITB attack before a successful injection occurs. Despite the fact that the scope for attack mitigation on an already compromised system is limited, we think that there still exist options for putting the attackers under significant pressure. Moreover, constantly updating the web browser can often disrupt a previously successful MITB. The focus should be on achieving simplicity in implementing a defensive methodology that makes implementing an attack as complicated as possible for the attacker. However, we consider the following suggestions from the point of view of the browser user's security, inspired by real examples mostly attacking Chrome, and not from the security developer's point of view, which might be quite different, or even diametrically opposed.

On the other hand, analyses of banking trojans show that methods that seem useful at the time might easily be bypassed by the next update of the bot. These include randomizing the names of browser processes (firefox.exe, chrome.exe, microsoftedgecp.exe, iexplore.exe, opera.exe), which may lead to a more complicated lookup for the right processes, but Figure 7 demonstrates a case where the bot actually did not rely on it at all.

Note that even the complete eradication of potential MITB attacks would not save web browsers from being abused. There is just as much potential for abuse by implementing a man-in-the-middle attack instead. Another important development of browser security in the context of MITB comes with advanced network protocols like HTTP/2.

The desire to incorporate these particular attacks into a malware project exposes its authors to the necessity of reversing the attack points, and of more advanced programming. Comparing the various projects, it seems that the authors generally do not copy from each other, neither do they rely on the legion of source code leaks. Unlike many ransomware projects, in this case the goal is handled by their own means. There is a certain potential to prevent MITB prior to any successful injections, taking the most powerful defensive action of making crucial attack points unexported and changing their position relative to each other with each major release. Needless to say, another reasonable approach is to use third-party protections that secure browser processes by encrypting keystrokes, or by providing an isolated environment that prevents code injection from remote processes.

[1] Boutin, J.-I. Evolution of WebInjects. Virus Bulletin 2014, Seattle. https://www.virusbulletin.com/uploads/pdf/conference/vb2014/VB2014-Boutin.pdf.

[2] Siebert, T. Advanced Techniques in Modern Banking Trojans. Botconf 2013, Nantes. https://www.botconf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/02-BankingTrojans-ThomasSiebert.pdf.

[3] Thomson, M. (ed. ); Belshe, M.; Peon, R. Hypertext Transfer Protocol Version 2 (HTTP/2). May 2015. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7540.

[4] Miller, M. Mitigating arbitrary native code execution in Microsoft Edge. February 2017. https://blogs.windows.com/msedgedev/2017/02/23/mitigating-arbitrary-native-code-execution.

[5] Marcos, M.J.S.; Inocencio,R.U. We have a 'DYRE' (dire) situation. AVAR 2015, Da Nang, 113-139.

[6] Pagnotta, S. CoreBot adquiere funcionalidades de troyano bancario. September 2015. https://www.welivesecurity.com/la-es/2015/09/14/corebot-troyano-bancario.

[7] Srokosz, P. Analysis of Emotet v4, Cert.pl. May 2016. https://www.cert.pl/en/news/single/analysis-of-emotet-v4.

[8] Kotowicz, M. ZeuS Meets VM – Story so Far. Botconf 2015, Nancy. https://www.botconf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/2014-3.6-ZeuS-Meets-VM-%E2%80%93-Story-so-Far.pdf.

[9] hasharasade. Floki bot and the stealthy dropper. November 2016. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2016/11/floki-bot-and-the-stealthy-dropper.

[10] hasharasade. Zbot with legitimate applications on board. January 2017. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/cybercrime/2017/01/zbot-with-legitimate-applications-on-board.

[11] Baz, M.; Gal, M. Dridex Gone Phishing. Botconf 2016, Lyon. https://www.botconf.eu/2016/dridex-gone-phishing/.

[12] MalwareTechBlog Let's Unpack: Dridex Loader. February 2017. https://www.malwaretech.com/2017/02/lets-unpack-dridex-loader.html.

[13] Kotowicz, M. ISFB: Stile Alive and Kicking. Botconf 2016, Lyon. https://journal.cecyf.fr/ojs/index.php/cybin/article/view/15.

[14] Schwarz, D. Another Banker Enters the Matrix. June 2017. https://www.arbornetworks.com/blog/asert/another-banker-enters-matrix/.

[15] Kotowicz, M; Jedynak, J. Nymaim: the Untold Story. Virus Bulletin 2016, Denver. https://www.virusbulletin.com/conference/vb2016/abstracts/last-minute-paper-nymaim-untold-story.

[16] Ortega, A. Nymaim Origins, Revival and Reversing Tales. Botconf 2016 Lyon. http://www.botconf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/PR18-Nymaim-ORTEGA.pdf.

[17] Zhang, X. Deep Analysis of the Online Banking Botnet TrickBot. December 2016. https://blog.fortinet.com/2016/12/06/deep-analysis-of-the-online-banking-botnet-trickbot.

[18] Boutin, J.-I. Qadars – a banking Trojan with the Netherlands in its sights. December 2013. https://www.welivesecurity.com/2013/12/18/qadars-a-banking-trojan-with-the-netherlands-in-its-sights/.

[19] Kessem, L.; Natan, H.; Laskov, D. Meanwhile in Britain, Qadars v3 Hardens Evasion, Targets 18 UK Banks. September 2016. https://securityintelligence.com/meanwhile-britain-qadars-v3-hardens-evasion-targets-18-uk-banks/.

[20] Karve S.; Venere G.; Olea M. Diving into Pinkslipbot's Latest Campaign. Virus Bulletin 2016, Denver. https://www.virusbulletin.com/conference/vb2016/abstracts/diving-pinkslipbots-latest-campaign.

[21] Oppenheim, M.; Zuk, K.; Meir, M.; Kessem, L. QakBot Banking Trojan Causes Massive Active Directory Lockouts. May 2017, IBM X-Force. https://securityintelligence.com/qakbot-banking-trojan-causes-massive-active-directory-lockouts/.

[22] Bremer, J. x86 API Hooking Demystified. July 2012. https://jbremer.org/x86-api-hooking-demystified/.

[23] Kessem, L. The NukeBot Trojan, a Bruised Ego and a Surprising Source Code Leak. March 2017. https://securityintelligence.com/the-nukebot-trojan-a-bruised-ego-and-a-surprising-source-code-leak/.

[24] Krebs, B. Self-Proclaimed 'Nuclear Bot' Author Weighs US Job Offer. April 2017. https://krebsonsecurity.com/tag/augustin-inzirillo/.

[25] Volatility Framework Command Reference Mal. https://github.com/volatilityfoundation/volatility/wiki/Command-Reference-Mal.

[26] browserhooks – plug-in for Volatility Framework. https://github.com/eset/volatility-browserhooks.

[27] Buescher, A.; Leder, F.; Siebert, T. Banksafe information stealer detection inside the web browser, in: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection (RAID), 2011, pp.262-280.

[28] Continella, A.; Carminati, M.; Polino, M.; Lanzi, A.; Zanero, S.; Maggi F. Prometheus: Analyzing WebInject-based information stealers, Journal of Computer Security, Feb 2017, pp.117-137.

[29] Wang, X. Protecting Financial Institutions from Man-in-the-Browser Attacks. Virus Bulletin 2014, Seattle. https://www.virusbulletin.com/uploads/pdf/conference/vb2014/VB2014-WangZhao.pdf.

| Banking trojan | SHA-256 |

| Win/TrickBot archive | 2cfb17d14897979a0b117d7c6ae3ec2b762f8ba2694887c4878d6f63692d0dca |

| Win/Spy.Ursnif archive | f30b5ae67a5fc51e7ccdfbcca344aec9cb1ca7216280243fa2652a2e6c41b07b |

| Win/Nymaim payload | e1e35f3e37257ea2788b2906811f6e9efbae4a9838c5a7c251d40842f4aa226e |

| Win/Spy.Ursnif.AX archive | de894706930dbe88bceb5c68f09956e2ab582cd2242c5e1d8e856b5407023ece |

| Win/Spy.Ursnif (ISFB) source code | 222c41a187cd3f7a48a6bdf68763f6db3a5ad3cd3ded718efa60aba7df3807fe |

| Win/Qbot archive | e549e403abafaeaa1fab0a7ac45fe8ed7e23aa8368813e56b0c06702e62904fd |

| Win/Dridex archive | 62cdda34da902b20e6175dc7db1f5a1642e225a716f1307d89c501c0dcd55c5e |

| Win/Qadars archive | 92694452df7d9c3c1cae798b1af5b4995134d38d11ffa1ca4f68303b0d107a12 |

| Win/Tinukebot (TinyNuke) source code | b76a0b3640f0577100909af2ad6e8b23456b866b22f8613782b91388abee2e34 |

| Win/Spy.Zbot (Floki) archive | 03fd627951ef4009f98956c424244b130f139d3ef3ae01fe6ec414a6c1abb18b |