Fortinet, France

Copyright © 2018 Virus Bulletin

The Spectre attack [1] has received massive coverage since the beginning of 2018, and by now, it is likely that everyone in computer science has at least heard about it. Spectre exploits the fact that speculative execution resulting from a branch misprediction may reveal private data to an attacker. Excellent explanations of the attack already exist, ranging from simple and short [2] to technical and detailed [1, 3].

Rather than being 'yet another paper' that explains Spectre, this one will focus on the probability of finding Spectre being exploited on Android smartphones. More precisely, we will answer two questions:

As ARM processors are currently predominant on Android smartphones, and as Spectre on Intel x86 has largely been covered already, this article focuses on Android smartphones with ARM processors.

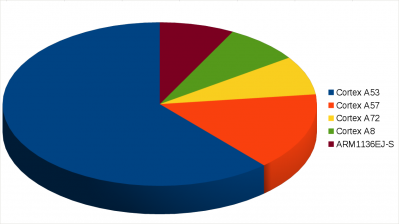

The ARM Cortex A53 [4] is a particularly nice pick for this study, because it is used in popular systems on chip (SoCs) (e.g. Qualcomm Snapdragon 410, 610, 615) and is therefore found on many smartphones, especially low-to-middle range ones. A quick survey among work colleagues confirms this distribution, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Distribution of ARM processors on Android smartphones in a department of Fortinet in January 2018.

Figure 1: Distribution of ARM processors on Android smartphones in a department of Fortinet in January 2018.

We will therefore use the ARM Cortex A53 as an example and try to determine whether Android smartphones using this processor are vulnerable to Spectre.

ARM has published a security advisory [5] in which it conveniently lists which processors are vulnerable to Meltdown and Spectre. The report explicitly states that processors that are not listed are not affected.

Good news! ARM Cortex A53 is not listed in the security advisory, which, according to the report, means it is not vulnerable. The document doesn't explain why, though, and it is quite perplexing because the specifications [6] of the processor rather indicate that it would be vulnerable. Indeed, we find in the specifications references to flags showing that there is speculative execution, including speculative execution of indirect branches, which is pertinent to Spectre versions 1 and 2. So is it vulnerable, or not? Without further explanation, the best solution is to test it.

In order to test in practice on an Android smartphone with an ARM Cortex A53, we need a proof of concept. At this stage, it is important to highlight that proofs of concept (PoCs) are not malware. Rather, they should be seen as demos that are used to show the feasibility of a given concept.

There are basically three types of PoC for Spectre:

None of these PoCs carry any malicious payload, and in fact, turning them into malware would involve a significant amount of work (e.g. communication between processes, shared memory, etc.).

One PoC in particular is interesting for this study: there is a port for Android AArch64 [7]. The ARM Cortex A53 is an ARMv8-A processor which supports 64-bit executables, with backward compatibility to ARMv7-A for 32-bit executables. So, the PoC should be suitable.

We cross-compile the PoC for our smartphone, push it on the device, and run:

git clone https://github.com/V-E-O/PoC/tree/master/CVE-2017-5753

NDK_DIR/build/tools/make_standalone_toolchain.py --arch arm64 --api SDK_NUMBER --installdir TOOLCHAIN_DIR

TOOLCHAIN_DIR/bin/aarch64-linux-android-gcc source.c -o spectre

adb push spectre /data/local/tmp

adb shell chmod u+x /data/local/tmp/spectre

adb shell /data/local/tmp/spectre

/system/bin/sh: ./spectre: not executable: 64-bit ELF file

The smartphone refuses to execute the PoC, complaining it cannot handle 64-bit executables. Indeed, when we check the CPU information on the smartphone, we do not see the expected ARMv8 model, but ARMv7.

shell@surnia :/ $ cat /proc/cpuinfo

processor : 0

model name : ARMv7 Processor rev 0 (v7l)

BogoMIPS : 38.00

Features : swp half thumb fastmult vfp edsp neon vfpv3 tls vfpv4 idiva idivt vfpd32 evtstrm

CPU implementer : 0x41

CPU architecture : 7

CPU variant : 0x0

CPU part : 0xd03

CPU revision : 0

This is quite common: it means we have a 64-bit capable processor, but we have a 32-bit stock kernel. So, there is no way this PoC will run on our smartphone – we need a 32-bit PoC for ARMv7.

Unfortunately, there is no PoC for ARMv7, so we decided to port it. The port is not an easy one, because some x86 instructions are missing in ARMv7. The official Spectre PoC implements a Flush+Reload cache attack, so we need (1) an instruction to flush the cache, and (2) an instruction to time access to memory accurately.

The x86 instructions _mm_clflush (cache flush) and rdtscp or rdtsc (time measure) do not exist on ARMv7. While we found a replacement for cache flush named __ARM_NR_cacheflush, there is no direct replacement for time measurement. However, the conclusions of prior research work [8, 9] present us with four alternative solutions:

After successfully porting the PoC (source code available at [10]), we ran it on our test smartphones. Some tuning was required, for instance to find the appropriate duration to differentiate a cache hit from a cache miss. That value is different for each system.

Yet, although the PoC ran, it failed to recover the secret phrase. In the output below, the recovered characters are 'o' followed by non-alphanumeric characters; this does not match the expected secret phrase which is 'The Magic Words are Squeamish Ossifrage'.

MAX_TRIES=5500 CACHE_HIT_THRESHOLD=364 len=40

Reading 40 bytes:

Reading at malicious_x = 0xffffe7e4 Unclear: 0x6F='o' score=809 (second best: 0xF0='?' score=806)

Reading at malicious_x = 0xffffe7e5 Unclear: 0xF3='?' score=809 (second best: 0xF6='?' score=808)

Reading at malicious_x = 0xffffe7e6 Unclear: 0xF0='?' score=877 (second best: 0xF6='?' score=847)

Reading at malicious_x = 0xffffe7e7 Unclear: 0xF0='?' score=839 (second best: 0xF6='?' score=829)

Note that the smartphones on which we tested the PoC were unpatched, as the mitigation for Spectre on AArch32 was only released in June 2018 [11] and not pushed to the test smartphones at this time.

Also, we conducted the same test on an old smartphone featuring an ARM Cortex A8 [12]. This ARMv7 CPU is interesting because ARM lists it as vulnerable to Spectre. Nonetheless, we obtained the same results as with the ARM Cortex A53, i.e. the secret phrase was not recovered when this CPU was used.

The most obvious conclusion to such a fail is that the test phones are not vulnerable to Spectre, or at least not to Flush+Reload implementations of Spectre, without substantial modification of the system. A lesson to be learned is that a vulnerable CPU is different from a vulnerable platform. As we have seen previously, ARM Cortex A8 is vulnerable as a CPU, but the vulnerability cannot be exploited over an Android OS stack.

Some additional research could be done to confirm this result:

Table 1 summarizes the findings.

| Spectre cache attack | Hacks | Smartphone | Results |

| Flush+Reload | None | Android with ARM Cortex A53 | Not vulnerable |

| Prime+Probe | None | Android with ARM Cortex A53 | To do (no known PoCs for this) |

| Evict+Reload | None | Android with ARM Cortex A53 | To do (no known PoCs for this) |

| Flush+Reload | Kernel module to access PMU | Android with ARM Cortex A53 | To do |

| Flush+Reload | None | Android with ARM Cortex A8 | Not vulnerable |

Table 1: Summary of findings.

In practice, the results mean that if you own an old Android smartphone or a low-to-middle range Android smartphone with an ARM Cortex A53, it is probably secure against Spectre attacks. There are only risks with a few recent high‑end smartphones, especially with ARM Cortex A57 and A72. In those cases, to be absolutely certain, it is better to test the PoC for AArch64 [7].

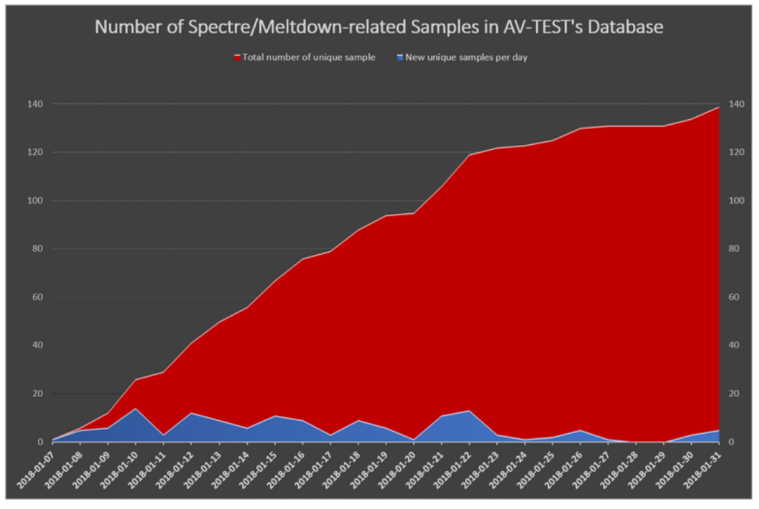

In February 2018, there were several headlines in the news stating 'Meltdown-Spectre malware is already being tested by attackers' and 'Meltdown and Spectre malware discovered in the wild'. The information was based on an AV-TEST graph [13], which, unfortunately, was misinterpreted, as we will see.

Figure 2: AV-TEST graph as Tweeted on 1 February 2018, reporting 139 unique samples for Spectre and Meltdown [13].

Figure 2: AV-TEST graph as Tweeted on 1 February 2018, reporting 139 unique samples for Spectre and Meltdown [13].

We checked each of the 139 samples reported by AV‑TEST, one by one. At that time, their names were the following:

All of these samples were proof of concepts. For the sake of clarity, in the case of Spectre, we renamed them all 'Riskware/SpectrePOC'. AV-TEST explicitly Tweeted an additional comment: 'The majority of samples are based on the known PoC codes [...] we also found the first working JavaScript PoC for Spectre' [13]. Note that AV-TEST speaks of samples and not malware. Unfortunately, the subtle difference between a sample, or a PoC, and a piece of malware went unnoticed (except by AV experts [14]) and led to major confusion with claims that 'Meltdown-Spectre malware' was in the wild. We re-iterate that there is a significant difference between a PoC of Spectre and a piece of malware using Spectre. Turning a PoC into a malicious executable is far from a trivial process.

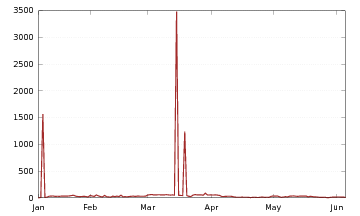

If we study detection hits for those Riskware/SpectrePOC samples, we get the following graph.

Figure 3: Detection hits on FortiGates for Riskware/SpectrePOC (Spectre proofs of concept).

Figure 3: Detection hits on FortiGates for Riskware/SpectrePOC (Spectre proofs of concept).

The graph shows an initial spike in early January, when we released the signatures for the Spectre PoCs. The second spike, in March, is presumed to correspond to the release of several Microsoft patches. Both spikes probably correspond to people testing Spectre PoCs on their infrastructures to assess vulnerability. We can also see a slight disinterest in Spectre starting in April 2018: before that date, besides spikes, we were registering approximately 40 hits per day (which isn't a lot); after April, it was more like 20 hits per day. This is slightly surprising as new versions of Spectre were released in May, but that did not seem to increase interest.

Even if there isn't any Spectre malware yet, that isn't to say that it won't happen one day. Researchers quickly tried to think of ways to detect Spectre. Some came up with the idea of detecting cache attacks with Linux perf [15], others by monitoring patterns of cache misses/cache hits [16], or by extending the Coverity static analysis tool [17], etc.

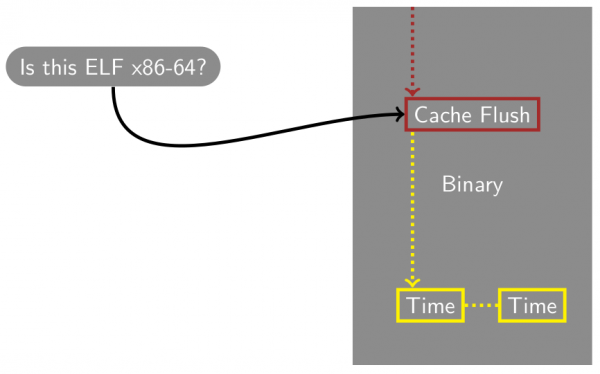

As an anti-virus researcher, I decided to craft a more or less generic AV signature to detect Flush+Reload cache attacks in ELF x86-64 executables (Figure 4). My goal wasn't to design a perfect signature (difficult, if not impossible), but something that would roughly work. I simply parsed the executable, looking for a cache flush instruction. If one was found, I would then look for two close rdtscp instructions.

Figure 4: Detecting Flush+Reload cache attacks in ELF x86‑64 executables.

Figure 4: Detecting Flush+Reload cache attacks in ELF x86‑64 executables.

Such a signature would not be acceptable in production because of poor performance (the entire binary needs to be scanned) and the high risk of false positives. But, for research, it is acceptable.

We ran the signature against all 62 ELF x86-64 PoCs of Spectre.

"./2FC4432E.vsc" is infected with the "Linux/FlushReload.A!tr" virus. VID: 888 S

IGID: 8888 SIGTYPE: C

"./2FC0C6A4.vsc" is infected with the "Linux/FlushReload.A!tr" virus. VID: 888 S

IGID: 8888 SIGTYPE: C

"./2FC4A10C.vsc" is infected with the "Linux/FlushReload.A!tr" virus. VID: 888 S

IGID: 8888 SIGTYPE: C

[Summary] Scanned: 62 Infected: 36 Total bytes: 1.614MiB Time: 0m0.001s

36 samples out of 62 were detected immediately. We investigated the remaining ones, and it appears they were all damaged: the cache flush instruction was missing. Without that instruction, Spectre won't run, so missing those samples is not very important.

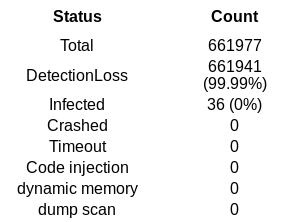

As a second test, we ran the signature against 661,977 recent malicious ELF samples from the last six months. The result was quite surprising because the signature detected no samples other than the Spectre PoCs.

Figure 5: Testing a research Flush+Reload cache signature on ELF samples.

Figure 5: Testing a research Flush+Reload cache signature on ELF samples.

This gives us some important information: Flush+Reload cache attacks are not common in ELF malware. Also, we had expected several false positives with this signature, but that was not the case: this imperfect signature turns out to be quite good in practice.

The take-aways of this work are the following:

The future is difficult to foresee. On the one hand, each time an attack goes public, malware authors use it sooner or later (usually quite soon). So, we might expect to see Spectre malware soon. On the other hand, this research work proves that cache attacks are difficult to implement, and perhaps not extremely well suited to mass infection because the malicious implementation will have to handle many CPUs, architectures and operating systems, and tune the attack for each of them. As long as there are easier ways for malware authors to make money, why would they embarrass themselves with such a technical choice? Nonetheless, the attack could certainly interest authors of targeted attacks (governments, political targets etc.).

This research was presented at the Pass The SALT conference. I particularly wish to thank Adam Shewchuk of Fortinet for helping me collect data, Ludovic Apvrille and Renaud Pacalet from Telecom Paristech for their explanations of ARM CPUs and speculative execution, and Daniel Gruss for his open discussion with me on implementation issues I met.

[1] Kocher. P. et al. Spectre Attacks: Exploiting Speculative Execution. https://spectreattack.com/spectre.pdf.

[2] Joubran, J. Spectre attack explained like you're five. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3-xCvzBjGs.

[3] Gruss, D. Software-based Microarchitecture attacks. https://gruss.cc/files/cryptacus2018.pdf.

[4] ARM Cortex A53. https://developer.arm.com/products/processors/cortex-a/cortex-a53.

[5] ARM, Vulnerability of Speculative Processors to Cache Timing Side-Channel Mechanics. Updated 31 May 2018. https://developer.arm.com/support/arm-security-updates/speculative-processor-vulnerability.

[6] ARM Cortex A53 specifications. https://static.docs.arm.com/dui0946/a/cycle_models_cortex_A53_Model_User_Guide_v8_0_0_DUI0946A_en.pdf.

[7] Spectre PoC for AArch64. https://github.com/V-E-O/PoC/tree/master/CVE-2017-5753.

[8] Lipp, M.; Gruss, D.; Spreitzer, R.; Maurice, C.; Mangard, S. ARMageddon: Cache Attacks on Mobile Devices, USENIX Security 2016.

[9] Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Return-Oriented Flush-Reload Side Channels on ARM and Their Implications for Android Devices, CCS 2016.

[10] Spectre PoC for ARMv7-A. https://github.com/cryptax/spectre-armv7.

[11] Phoronix. 32-bit ARM Finally Gets Mitigiated For Spectre V1/V2 With Linux 4.18. https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=Spectre-32-bit-ARM-Linux-4.18.

[12] ARM Cortex A8. https://developer.arm.com/products/processors/cortex-a/cortex-a8.

[13] AV-TEST Tweet. 1 February 2018. https://plus.google.com/photos/photo/100383867141221115206/6517535568830348546.

[14] Grooten, M. There is no evidence in-the-wild malware is using Meltdown or Spectre. 2 February 2018. https://www.virusbulletin.com/blog/2018/02/there-no-evidence-wild-malware-using-meltdown-or-spectre/.

[15] Capsule 8. Part Two: Detecting Meltdown and Spectre by Detecting Cache Side Channels. 9 January 2018. https://capsule8.com/blog/detecting-meltdown-spectre-detecting-cache-side-channels/.

[16] Israel, E.; Marx, D.; Alon, Y.; Gafni, A.; Omelchenko, B. Detection of the Meltdown and Spectre Vulnerabillities. 8 January 2018. https://research.checkpoint.com/detection-meltdown-spectre-vulnerabilities-using-checkpoint-cpu-level-technology/.

[17] Synopsys, Detecting Spectre vulnerability exploits with static analysis. 22 March 2018. https://www.synopsys.com/blogs/software-security/detecting-spectre-vulnerability-exploits-with-static-analysis/.