City University London, UK

Intel Security, UK

Swansea University, UK

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

Mobile operating systems support multiple communication methods between apps. Unfortunately, these handy inter-app communication mechanisms also make it possible to carry out harmful actions in a collaborative fashion. Two or more mobile apps, viewed independently, may not appear to be malicious. Together, however, they could become harmful by exchanging information with one another. Multi-app threats such as these were considered theoretical for some years. Yet as part of our efforts to develop methods to detect collusions, we have found colluding code embedded in multiple applications in the wild. In this paper, we provide a concise definition of mobile app collusion, explain how mobile app collusion can happen in the wild, and describe countermeasures to protect devices from such attacks.

Modern mobile operating systems incorporate many techniques to isolate apps in sandboxes, restrict their capabilities, and clearly control which permissions they have at a fairly granular level. However, operating systems also include fully documented ways for apps to communicate with each other across sandbox boundaries. In Android, for example, this is often done via intents, which are essentially inter-process (or inter-app) messages.

Looking to evade detection by mobile security tools and by malware and privacy filters employed in app markets, attackers may try to leverage multiple apps with different capabilities and permissions to achieve their goals – for example, using an app with permitted access to sensitive data to communicate with another app that has Internet access. This collusion technique is difficult to detect, as each app will appear to most tools to be benign, potentially enabling attackers to penetrate more devices and for a longer time before they are caught.

This kind of attack is possible because sandboxed systems, such as Android, are designed to avoid threats created by single apps. This approach to security is also followed by other malware protection systems, which generally analyse applications as isolated entities. Although this behaviour is not widespread today, it opens an avenue to circumvent sandboxed operating systems, and Android is its best example.

In this paper we present a concise definition of app collusion, including the threats that can be created by these apps and the communication channels they may use to collude. We describe how colluding apps have operated for a long time, without being detected, in a large group of applications that use a malicious version of the library MoPlus SDK. Finally, we discuss the main countermeasures that can be put in place to prevent such attacks.

The origins of application collusion can be traced to the 'confused deputy' attack, as described by Hardy in 1988 [1]. Confused deputies expose protected resources through public interfaces. In Android, confused deputy attacks can happen in the form of 'permission redelegation attacks' [2, 3, 4]. A careless developer may unintentionally expose permission-protected resources when allowing the components that access those resources to communicate with other applications through IPC. This is beneficial for the attacker because the malicious application does not declare the usage of the protected resources, but ends up using them.

The first documented example of collusion is Soundcomber [5]. This proof-of-concept malware is composed of two apps. The first app requires access only to the device microphone (RECORD_AUDIO permission), listens for calls to telephone banking services and extracts the digits pressed by the user. The second app receives the extracted sensitive information and sends it to a remote server (INTERNET permission).

In this work, 'collusion' refers to the ability of a set of apps to carry out an attack in a collaborative fashion. Our definition is not restricted only to information theft attacks, as in the Soundcomber example and other works [6, 7]. In fact, the colluding behaviour identified in the wild does not follow this pattern. The Soundcomber example shows the difference between app collusion and confused deputy attacks. In application collusion, the exposure of the sensitive resource is intentional. Confused deputies (through permission redelegation) occur only when a programmer accidentally creates a vulnerable app. Unfortunately, distinguishing between the two attacks is a challenging task because they generate the same traces on the user's device.

Colluding apps can carry out any attack such as the ones carried out by single apps [8]. However, collusion can also be used to synchronize the execution of multiple apps. The following list enumerates attacks that can be performed by colluding apps:

Colluding applications can use standard communication channels such as intents to execute their attacks. However, an attacker may also use stealthier communication options to avoid detection. The following presents a list of communication possibilities in Android that can be misused by colluding applications:

An intent is a messaging object that is used to request actions from other apps' components. These can belong to the same or different apps. Intents can be explicit or implicit. Explicit intents target specific activities or services (for example, an activity invoking a specific activity or service from the same app) while implicit intents target generic actions that can be performed by many recipients (for example, sending a message, opening a web link, etc.). Activities, services, and broadcast receivers define the intents that they can handle by declaring a set of intent filters. For activities and services, intent filters must be declared in the app's manifest XML file. Broadcast receivers can also register their intent filters programmatically during execution.

Although later versions of Android implement SELinux, intents are not covered by the mandatory access controls imposed by SELinux, as their semantics are not compatible [9]. Intents can be used by colluding apps to share information just as any other benign application does. Broadcast receivers and services allow applications to exchange data without user intervention.

A content provider offers to other apps a method to access structured data from the app to which the content provider belongs. Content providers store information in one or more tables, in a similar way to relational databases. Apps access data of content providers using content resolver objects. A content provider offers methods that can be called by others apps, not only to read data but also to update, create and delete information encapsulated in the content provider object.

Malicious applications can use already available content providers as a drop box in order to exchange information. Access to the system content providers sometimes requires applications to request corresponding permissions (such as WRITE_CONTACTS to access the contact database).

Android allows applications to access a partition of storage that is shared by all applications. Generally, external storage is available through a USB connection, SD card, or even a partition inside the main flash drive of the device. Apps accessing the external storage need to declare the READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE permission. Apps declaring the WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE can write to and read from external storage. Applications with access to external storage can access all files inside it, as no access restriction is applied. Files in the external storage can be accessed using the common file access API. The external storage of an Android device could also be used by colluding applications as a shared drop box to exchange information.

Shared preferences are an Android feature that allows apps to store key-value pairs of data. The purpose of shared preferences is to store app configuration and preferences. Although it is not intended for inter-app communication, apps can use key-value pairs to exchange information if proper permissions are defined (prior to Android 4.4). To do so, applications need to use the flags WORLD_WRITABLE or WORLD_READABLE. Since the adoption of SELinux (from Android 4.4) an app cannot access the world readable files of other applications, as both apps are confined to different SELinux domains.

Colluding apps can also use standard Unix sockets to communicate. Apps can use sockets opened to the localhost to communicate as if they were communicating via a network. Communication between two apps that is mediated by an external server is not generally considered as collusion, as the communication happens outside the device.

Covert channels in Android can take advantage of some of the APIs or features offered by the operating system to enable communication between processes [10, 11]. In Android, this includes the use of public readable and writable settings (such as volume level) and the capture of broadcast intents generated by the system in certain events that can be triggered by apps (for example, wake lock). Processes can also take advantage of covert channels that are general to most computing systems such as file locks, process enumeration, socket discovery, free storage space, available memory, and CPU usage.

One of our first tasks in trying to identify collusion attempts in the wild has been to analyse not-so-standard communication channels in Android [12]. Specifically, we investigated how shared preferences were used for communication in a set of more than 50,000 apps. These apps were collected and categorized by Intel Security into three groups: malware, potentially unwanted programs (PUPs), and clean (see Table 1).

| Malware | PUPs | Clean | |

| Number of apps | 13,805 | 13,991 | 22,378 |

| Overall installs | 3,696,720 | 7,656,755 | 21,205,724,533 |

| Average size in KB | 3,007.9 | 7,394.52 | 10,208.3 |

Table 1: Summary of analysed apps (from 14 February 2012 to 6 February 2016).

In our analysis, we found that some of the apps in the PUP set were capable of reading files that originated from different app packages. A manual review of these apps revealed that they were exchanging data through shared preferences files to synchronize the execution of a potentially harmful payload. This payload was included inside a library embedded in these applications. This library, known as MoPlus SDK, has been known to contain remote-control capability (essentially a backdoor) since November 2015 [13]. However, the collusion behaviour of this SDK had not previously been discovered. We were able to identify 5,056 APKs belonging to 20 apps. The actual number of affected apps in the wild is likely to be higher than the list in Table 2.

| Package name | |

| com.baidu.BaiduMap | com.baidu.appsearch |

| com.baidu.browser.apps | com.baidu.hao123 |

| com.baidu.netdisk | com.baidu.searchbox |

| com.baidu.video | com.dragon.android.pandaspace |

| com.hiapk.marketpho | com.ifeng.newvideo |

| com.managershare | com.mfw.roadbook |

| com.nd.android.pandahome2 | com.qiyi.video |

| com.quanleimu.activity | com.tuniu.app.ui |

| com.yuedong.sport | tv.pps.mobile |

| com.android.comicsisland.activity | com.dongqiudi.news |

Table 2: Selection of package names known to include the affected version of the MoPlus SDK.

In the rest of this section we briefly describe the malicious behaviour of this SDK and provide a more detailed analysis of its colluding behaviour.

The MoPlus SDK (versions up to Q4 2015) can open a local HTTP server on the user device. This enables the attacker to perform a series of malicious operations, including:

The malicious payload embedded inside the MoPlus SDK inherits all permissions requested by the application. As these are chosen by the app developer, it is possible that an app including the SDK will not have the necessary permissions to execute all of the malicious payload. The colluding behaviour of the MoPlus SDK aims to execute the malicious payload in the process with the maximum amount of privileges.

Application collusion research has focused mainly on trying to detect flows of sensitive information across applications. However, the colluding behaviour exhibited by the MoPlus SDK differs from this kind of collusion. In a nutshell, all apps running on a device that include the MoPlus SDK will talk to each other to determine which of these apps has the most privileges. The app with the most privileges will be the only one executing a local HTTP server to receive commands from the control server. In distributed computing this kind of behaviour is known as leader election. In the next sections we describe this behaviour in detail with reverse-engineered code samples. These have been obtained from the Baidu search box app (SHA256: 36bd6418afeaba44eab45793ff8a70ad016708053c6a9c1ff056e6bdd05072d1). Locations of shown payloads may differ from one application package to another, as Android app code is generally obfuscated using ProGuard.

The analysed version of the MoPlus SDK includes the MoPlusService and the MoPlusReceiver app components. In all analysed apps, the MoPlusService is configured as exported in the manifest. In Android this is considered to be a high-risk practice, as all other apps will be able to call and access the service.

During the MoPlus SDK initialization, the MoPlusService is created inside each of the apps with the MoPlus SDK. During service creation (see Code 1), the MoPlus SDK executes three checks on the package of the application in which it runs:

If any of these three checks fails, the service instance assigns itself a priority of 0 inside a preference file that can be read by the rest of the applications installed in the system. The name of the preference file is created by concatenating the package name to 'push_sync'. The SDK uses the WORLD_READABLE flag (value 1) to save the file so other apps can access it.

public static void e(Context paramContext, boolean paramBoolean){

SharedPreferences localSharedPreferences = paramContext.getSharedPreferences("pst", 0);

int i = c(paramContext, paramContext.getPackageName());

int j = localSharedPreferences.getInt("pr_v", 0);

SharedPreferences.Editor localEditor1;

if ((j < i) || (paramBoolean))

{

Log.d("Utility", "oldVCode=" + j + "vcode=" + i + "isForce" + paramBoolean);

localEditor1 = paramContext.getSharedPreferences(paramContext.getPackageName() + ".push_sync", 1).edit();

if ((!a(paramContext)) && (j(paramContext)))

break label197;

localEditor1.putLong("priority", 0L);

}

while (true)

{

localEditor1.putInt("version", 121);

localEditor1.commit();

SharedPreferences.Editor localEditor2 = localSharedPreferences.edit();

localEditor2.putInt("pr_v", i);

localEditor2.commit();

return;

label197: localEditor1.putLong("priority", f(paramContext));

}

}

Code 1: This method checks for execution conditions. This code is included in the class com.baidu.android.moplus.util.a.

If the three checks hold, the service assigns itself a priority that depends on several factors (see Code 2). These include, from lowest to highest priority:

public static long f(Context paramContext){

long l1 = 0L;

if (paramContext == null)

return l1;

if (!g(paramContext, paramContext.getPackageName()))

l1 += 1L;

long l2 = l1 << 1;

if (!i(paramContext))

l2 += 1L;

long l3 = l2 << 1;

if (!f(paramContext, paramContext.getPackageName()))

l3 += 1L;

long l4 = l3 << 1;

if (d(paramContext, paramContext.getPackageName()))

l4 += 1L;

long l5 = l4 << 1;

if (p(paramContext))

l5 += 1L;

long l6 = l5 << 1;

if (b(paramContext, paramContext.getPackageName()))

l6 += 1L;

return 0x79000000000000 | (l6 | 0xFF & i(paramContext, "moplus_addon_priority") << 40);

}

Code 2: The MoPlus SDK uses this method to assign priority execution to each app's MoPlusService. This code is included in the class com.baidu.android.moplus.util.a.

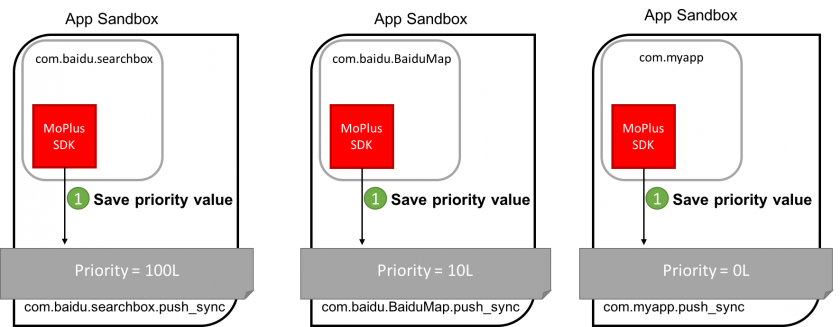

The obtained priority value is saved in the previously referenced preference file '.push_sync'. This behaviour is executed by all apps, including the MoPlus SDK. In this way, each app holds a shared preference file reflecting the access level (priority) that the app has to required resources (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Each app saves a priority value that depends on the amount of access it has to the system resources. Priority values have been calculated to illustrate this explanation.

Figure 1: Each app saves a priority value that depends on the amount of access it has to the system resources. Priority values have been calculated to illustrate this explanation.

After the priority has been obtained and stored, the OnCreate method of the service calls method 'a' (see Code 3) to create and broadcast a new intent object.

public static void a(Context paramContext, long paramLong){

Context localContext = paramContext.getApplicationContext();

Intent localIntent = c(localContext);

localIntent.setPackage(d(localContext));

a(localContext, localIntent, paramLong);

}

Code 3: Creating the intent object. The inner a() method is used to broadcast it.

The localIntent object is obtained from the execution of the method c(Context) (see Code 4), which creates the intent that will start MoPlusReceiver.

public static Intent c(Context paramContext){

Intent localIntent = new Intent("com.baidu.android.moplus.action.START");

localIntent.addFlags(32);

localIntent.putExtra("method_version", "V1");

return localIntent;

}

Code 4: Intent creation method.

The call to 'd' in Code 3 tells the intent to be sent only to the package with the highest stored priority value. This is executed through the method a(Context), which simply forwards the call to another method, a(Context,'push_sync', 'priority') (see Code 5).

public static String d(Context paramContext){

return a(paramContext, ".push_sync", "priority");

}

Code 5: This method forwards the call to return the app package with the highest priority.

Finally, the method a(Context, String, String) looks for all the packages that can answer the intent actions included in the MoPlus SDK (see Code 6). These are:

public static String a(Context paramContext, String paramString1, String paramString2){

List localList = h(paramContext);

if ((localList == null) || (localList.size() <= 1))

{

localObject1 = paramContext.getPackageName();

return localObject1;

}

long l1 = paramContext.getSharedPreferences(paramContext.getPackageName() + ".push_sync", 1).getLong("priority", 0L);

String str = paramContext.getPackageName();

Iterator localIterator = localList.iterator();

l2 = l1;

localObject1 = str;

while (localIterator.hasNext())

{

localObject2 = ((ResolveInfo)localIterator.next()).activityInfo.packageName;

SharedPreferences localSharedPreferences2 = paramContext.createPackageContext((String)localObject2, 2).getSharedPreferences((String)localObject2 + paramString1, 1);

. . .

}

}

Code 6: This method inspects all SharedPreference files of the packages that can answer the MoPlus SDK actions and returns the package name with the highest priority.

For each of the packages found, the app inspects the contents of the .push_sync file to retrieve its priority, selecting the package name of the file with the highest priority. After the package name has been selected, the intent is sent to the system through the method a(Context, Intent, long) (see Code 7), which cancels previous intents that have been registered (to avoid launching the service more than once) and, after a delay, sends the intent passed as a parameter.

public static void a(Context paramContext, Intent paramIntent, long paramLong){

PendingIntent localPendingIntent = PendingIntent.getBroadcast(paramContext, 0, paramIntent, 268435456);

AlarmManager localAlarmManager = (AlarmManager)paramContext.getSystemService("alarm");

localAlarmManager.cancel(localPendingIntent);

localAlarmManager.set(3, paramLong + SystemClock.elapsedRealtime(), localPendingIntent);

}

Code 7: This method cancels previous intents matching the service, and registers a new intent to be launched after a certain delay defined by the parameter passed to the method.

All apps that include the MoPlus SDK library exhibit this behaviour (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Representation of the com.myapp while it executes the highest priority receiver.

Security vendors offer Android products that protect smartphones and tablets by scanning individual installation packages (APKs) and blocking unwanted ones. Colluding apps can be blocked using the same technique, but the catch is to have tools that recognize that they are colluding. The goal of our collaborative project (www.acidproject.org.uk) is to develop practical tools for collusion discovery.

Developers of apps may improve their software and protect their own reputations by avoiding unknown third parties and ad libraries, especially when they are closed source. It is also a good idea to avoid using multiple SDKs and ad libraries in an app. This last measure reduces the risk of collusion and also reduces mobile data usage for users.

App market vendors would benefit from employing anti-collusion filters to block the publication of such apps. It is also a good idea to set and enforce a sensible policy on inter-app communications and explicitly prohibit developers to violate operating system limitations through collusion methods.

Collusions are part of a bigger and more general problem of effective software isolation [14]. The same problem exists in all environments that implement software sandboxing, from other mobile operating systems to virtual machines in server farms. The tendency to have more and better isolation is positive and we should expect attackers to employ collusion methods more often to circumvent this security trend. Covert communications across sandboxes will likely be one of the attack vectors of tomorrow.

This work has been supported by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), under the BACHUS call (EP/L022699/1). A special thanks goes to Erwin R. Catesbeiana Jr. for excellent guidance through the Android ecosystem.

[1] Hardy, N. The Confused Deputy: (or why capabilities might have been invented). 1988. ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, 22(4), pp.36–38.

[2] Felt, A. P.; Wang, H. J.; Moshchuk, A.; Hanna, S.; Chin, E. Permission Re-Delegation: Attacks and Defenses. 2011. USENIX Security Symposium.

[3] Davi, L.; Dmitrienko, A.; Sadeghi, A.-R.; Winandy, M. Privilege escalation attacks on Android. 2011. Information Security, pp.346–360.

[4] Wu, L.; Du, X.; Zhang, H. An effective access control scheme for preventing permission leak in Android. 2015. International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC) pp.57–61. IEEE.

[5] Schlegel, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, X.-y.; Intwala, M.; Kapadia, A.; Wang, X. Soundcomber: A stealthy and context-aware sound trojan for smartphones. 2011. NDSS, 11, pp.17–33.

[6] Marforio, C.; Francillon, A.; Capkun, S. Application collusion attack on the permission-based security model and its implications for modern smartphone systems. 2011. https://www.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/infk/inst-infsec/system-security-group-dam/research/publications/pub2011/724.pdf.

[7] Bugiel, S.; Davi, L.; Dmitrienko, A.; Heuser, S.; Sadeghi, A.-R.; Shastry, B. Practical and lightweight domain isolation on Android. 201. Proceedings of the 1st ACM workshop on Security and privacy in smartphones and mobile devices pp.51–62.

[8] Suarez-Tangil, G.; Tapiador, J.; Peris-Lopez, P.; Ribagorda, A. Evolution, detection and analysis of malware for smart devices. 2014. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 16(2): 961–987.

[9] Jing, Y.; Ahn, G.-J.; Doupé, A.; Yi, J. Checking Intent-based Communication in Android with Intent Space Analysis. 2016. Proceedings of ASIA CCS 2016. Xian: ACM.

[10] Schlegel, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, X.-y.; Intwala, M. Soundcomber: A Stealthy and Context-Aware Sound Trojan for Smartphones. 2011. NDSS, 11, pp.13–33.

[11] Marforio, C.; Ritzdorf, H.; Francillon, A.; Capkun, S. Analysis of the communication between colluding applications on modern smartphones. 2012. Proceedings of the 28th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference pp.51–60.

[12] Mariuca Asavoae, I.; Blasco, J.; Chen, T. M.; Kumara Kalutarage, H.; Muttik, I.; Nguyen, H. N.; Roggenbach, M.; Shaikh, S. A. Towards Automated Android App Collusion Detection. 2016. Innovations in Mobile Privacy and Security, 1575, pp.29–37.

[13] Shen, S. Setting the Record Straight on Moplus SDK and the Wormhole Vulnerability. 2015. http://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/setting-the-record-straight-on-moplus-sdk-and-the-wormhole-vulnerability/.

[14] McAfee Labs (Intel Security). McAfee Labs Threats Report June 2016. http://www.mcafee.com/us/resources/reports/rp-quarterly-threats-may-2016.pdf.