Check Point Software Technologies, Belarus & Israel

Copyright © 2017 Virus Bulletin

Without any doubt, 2016 was the year of ransomware. What makes ransomware so attractive to attackers is that it offers the possibility of large profits while not requiring too much effort. With the availability of ransomware-as-a-service, someone with very little actual knowledge of computers can easily manage a highly profitable campaign.

A wide variety of different ransomware families appeared over the course of the last year, including Locky, CryptoWall and CryptXXX, to name just a few. Let's talk about the very profitable Cerber.

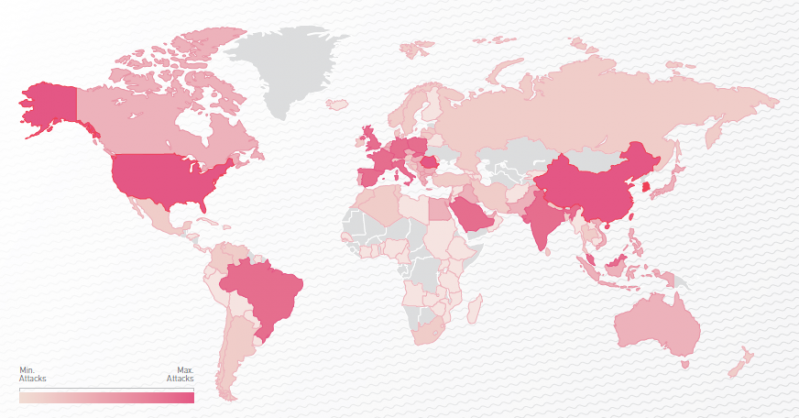

The Cerber ransomware was mentioned for the first time in March 2016 on some Russian underground forums, on which it was offered for rent in an affiliate program. Since then, it has been spread massively via exploit kits, infecting more and more users worldwide, mostly in the APAC (Asia-Pacific) region. At the time of writing this paper, there are six major versions.

There have been multiple successful attempts to decrypt users' files without paying a ransom. At the end of July 2016, Trend Micro released a partially working decryptor for the first version of Cerber [1]. In early August, we had a chance to take a look at the original Cerber decryptor code that was available for download upon payment of the ransom. Our main goal was to discover a flaw, based on the standard approaches we use against ransomware.

From our perspective, it wouldn't be as much fun if this was one of the expected bugs – and fortunately, the one we discovered wasn't. However, as with any flaw, you need to hide the solution from the criminals. In an ironic twist, the ransomware authors released a new Cerber 2 version the day before we were due to release the decryptor.

In order to be able to provide our decryption tool to as many victims as possible, we gathered forces and adapted it to the new version on the same day, thus managing to release it on time. The tool was used by many victims worldwide.

This paper details the story of the ransomware's fatal flaw and our free decryption service [2, 3]. We will dive deep into the background of Cerber as a service, the business operations, the money flow between the attacker and the affiliate, full global infection statistics and the estimated overall profit of the criminals [4].

In this paper we discuss one of the largest recent ransomware campaigns, known as Cerber. We describe the ransomware's encryption routine and reveal technical details of the server-side vulnerability that was used for the successful decryption of thousands of infected machines. We also share information on the money flow and estimated overall profit of the criminals, together with the tools used to collect that information. The decryption software will be available as open source on our GitHub repository [5].

Let's describe the encryption scheme used by the Cerber ransomware. It uses mix of symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms, such as RC4 and RSA. Almost all the encryption keys are generated randomly on the victim's machine.

First, let's take a look at the keys that are used by Cerber during the encryption process:

| Key | Appearance/description | Scope |

| RSA_M_PUB (2048 bits) |

Configuration This is a master public key |

Global |

| RSA_X_PUB/PRI (X bits) |

Random This is a local key pair |

Global |

| RC4_KEY (128 bytes) | Random | Per file |

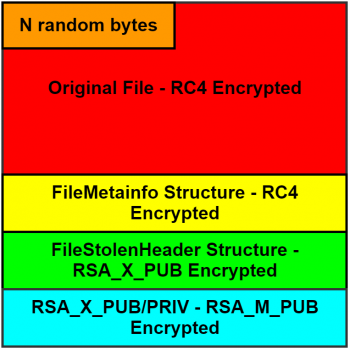

The structure of the encrypted file is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Structure of encrypted file.

Figure 1: Structure of encrypted file.

The goal of the encryption routine is to encrypt a single file from the file system. The number of bytes that are stolen from the beginning of each encrypted file (hereafter called N) is calculated once and depends on the local RSA key size. The steps performed by Cerber to encrypt a single file are as follows:

| Information | Algorithm | Key |

| FileMetainfo | RC4 | RC4_KEY |

| FileStolenHeader | RSA | RSA_X_PUB |

| RSA_X_PUB/PRI | RSA | RSA_M_PUB |

Two main data structures that represent the encrypted file are presented below:

struct FileStolenHeader {

char ver_magic[4]; // magic header (version)

uint32_t rand_bytes; // random bytes

uint16_t fn_len; // Unicode filename length

uint8_t blocks; // blocks to encrypt

uint32_t block_size; // block size

uint16_t N_to_steal; // number of bytes to steal

uint32_t N_bytes_mmh; // murmur3 hash of stolen

char RC4_KEY[16]; // RC4_KEY

char stolen_bytes[0]; // stolen bytes

};

struct FileMetainfo {

FILETIME Creation; // original CR time

FILETIME LastAccess; // original LA time

FILETIME LastWrite; // original LW time

char orig_fn[0]; // original filename

uint64_t blocks_mmh[0]; // murmur3 hash of blocks

};

The overall structure of an encrypted file was presented in Figure 1, however this can vary depending on the size of encrypted file.

If a single block is encrypted:

struct EncryptedFile {

char rand_bytes[N]; // stolen bytes repl

char ct[FileSize-N]; // encrypted file data

FileMetainfo enc_fmi; // encrypted FMI stru

char enc_fsh[0]; // encrypted FSH stru

char enc_RSA_X[0]; // encrypted RSA_X_*

};

If multiple blocks are encrypted:

struct EncryptedFile {

char rand_bytes[N]; // stolen bytes repl

char pt_0[K]; // plaintext chunk

char ct_0[max_block_size]; // ciphertext chunk

...

char pt_y[M]; // plaintext chunk

char ct_y[max_block_size]; // ciphertext chunk

FileMetainfo enc_fmi; // encrypted FMI stru

char enc_fsh[0]; // encrypted FSH stru

char enc_RSA_X[0]; // encrypted RSA_X_*

};

If the file is small:

struct EncryptedFile {

char rand_bytes[N]; // stolen bytes repl

FileMetainfo enc_fmi; // encrypted FMI stru

char enc_fsh[0]; // encrypted FSH stru

char enc_RSA_X[0]; // encrypted RSA_X_*

};

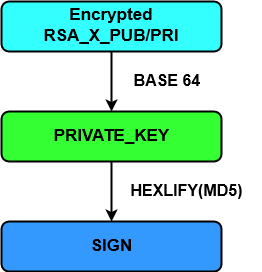

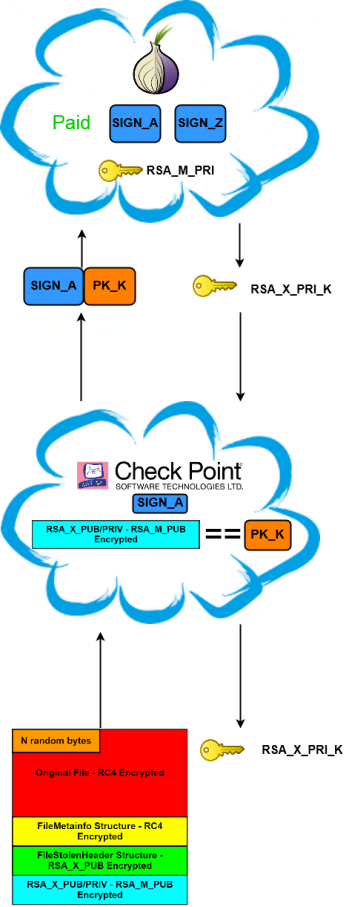

Let's discuss the decryption scheme that is used by the Cerber ransomware, after the ransom has been paid. An overview of the decryption scheme is shown in Figure 2.

The following steps are performed by the decryptor in order to restore encrypted files:

As we can see, the decryption routine is not complicated. The only blind spot is the RSA_M_PRI key. Factorization of a 2048-bit number is a nice challenge [6], but is definitely not what we want to deal with, because cracking such a long key is not feasible in a reasonable amount of time.

Let's take a look at how the decryptor communicates with the server in order to obtain RSA_X_PRI, which is critical for the decryption process. The decryptor encodes ENC_RSA_X_BLOB using a base64 algorithm (hereafter PRIVATE_KEY). The ID of the infected machine is calculated as an MD5 of the previously encoded block (hereafter SIGN) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Signature generation.

Figure 3: Signature generation.

The first message contains only the machine ID, which is sent using the following format:

"sign=%s" % SIGN

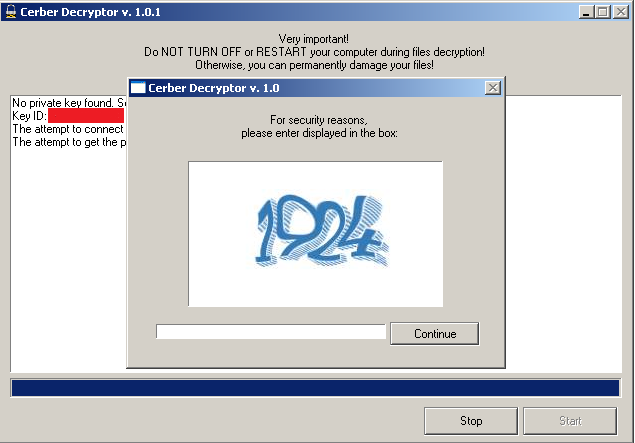

The response from the server contains a CAPTCHA image, which must be solved to continue decryption. We assume that this is done to protect the decryption server from the DDoS.

Figure 4: CAPTCHA.

Figure 4: CAPTCHA.

The CAPTCHA solution, together with PRIVATE_KEY and SIGN, are sent to the server using the following format:

"captcha=%d&sign=%s&private_key=%s" % (CAPTCHA, SIGN, PRIVATE_KEY)

If the CAPTCHA has successfully been solved and the specified machine ID has made the ransom payment, the server decrypts RSA_X_PRI and sends it back to the client. Then the decryptor starts the file restore process.

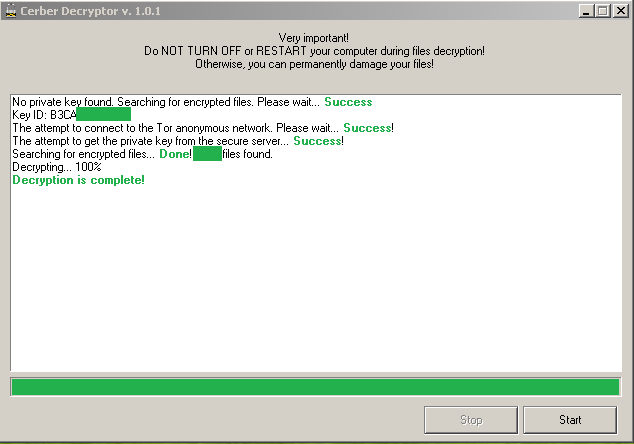

Figure 5: Successful decryption.

Figure 5: Successful decryption.

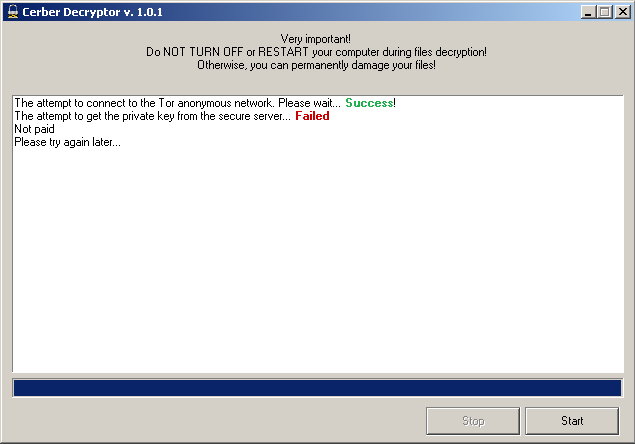

If the ransom for the specified machine ID is not paid, the user receives the message shown in Figure 6 during communication with decryption server.

Figure 6: Ransom not paid.

Figure 6: Ransom not paid.

Now we have familiarized ourselves with the decryption scheme and communication method, let's consider what can go wrong in the existent solution.

This section describes the approaches that were used to find a flaw in the decryptor. First, we should understand how exactly the server validates that the ransom has been paid for a specific machine. The most obvious answer is the use of the SIGN field. If the ransom is paid for SIGN, the server decrypts PRIVATE_KEY and sends RSA_X_PRI to the user. Let's try to rewrite the server code that is responsible for handling decryption requests from users based on received responses:

def handle_request_decrypt_private_key(packet):

if not captcha_correct(packet['captcha']):

send('{"error": "Captcha expired or invalid"}')

return

if not paid(packet['sign']):

send('{"error":"Not paid"}')

return

pk = urls_to_b64(packet['private_key'])

#**********************************************

# DOES SERVER SIDE HAVE SUCH INTEGRITY CHECK ?#

if md5(pk).hexdigest() != packet['sign'])

send('{???}')

return

#**********************************************

RSA_X_PRI = decrypt(b64decode(pk))

send('{"error": "null", "private_key": "%s"}' %\

encode(RSA_X_PRI))

Now let's try to recreate the server's exact behaviour based on the received responses and common sense:

The first two steps can easily be checked by sending an incorrect CAPTCHA solution and SIGN that is unpaid. The third step is what we are really interested in.

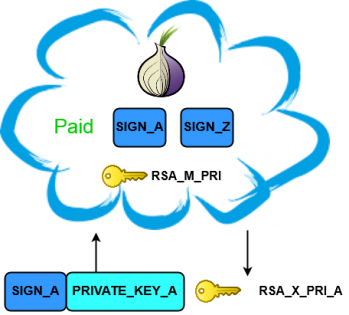

Let's imagine that SIGN_A signature is paid and we have a possibility to restore RSA_X_PRI_A. RSA_X_PRI_A is restored from the PRIVATE_KEY data that is under the sender's control. So what happens if the user spoofs that data?

Figure 7: Original PRIVATE_KEY for the paid SIGN.

Figure 7: Original PRIVATE_KEY for the paid SIGN.

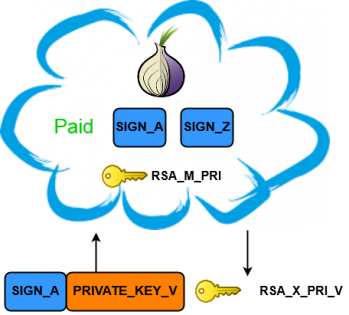

Let's think what exactly we can achieve by setting PRIVATE_KEY to prepared data assuming SIGN_A is paid. What will happen if we can calculate PRIVATE_KEY_V for another infection? Assuming that a data integrity check is absent, then the server will simply decrypt PRIVATE_KEY_V and extract RSA_X_PRI_V, thus giving the possibility to restore infected files for the user who hasn't paid! By applying the same tactics to all infected machines, we can restore them by using only one valid SIGN.

If the server does not perform an integrity check of the PRIVATE_KEY data, then it is decrypted and the RSA_X_PRI_V key is sent to the user. The user then adopts that key to restore encrypted files.

Figure 8: Spoofed PRIVATE_KEY for the paid SIGN.

Figure 8: Spoofed PRIVATE_KEY for the paid SIGN.

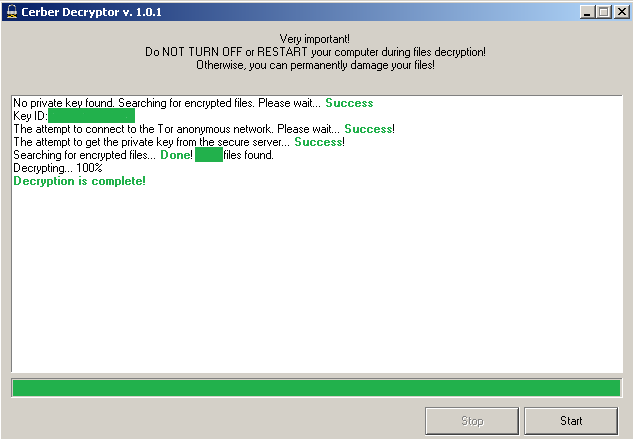

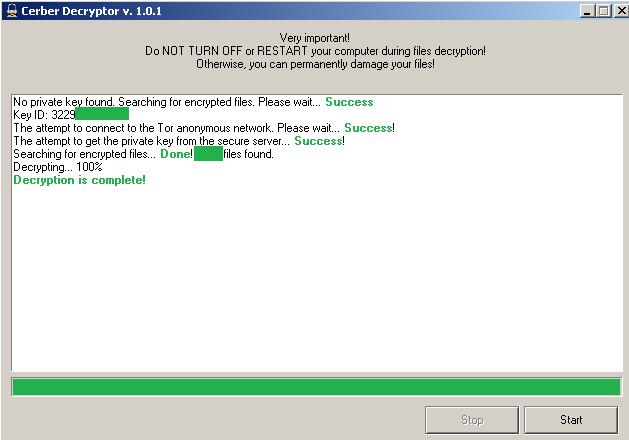

To showcase this theory we paid the ransom for one infection that was performed on a specially prepared machine. All the checks on the server side passed and the decryption process succeeded (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Successful decryption for original PRIVATE_KEY.

Figure 9: Successful decryption for original PRIVATE_KEY.

Next, a second machine was infected and encrypted with the Cerber ransomware. It obviously had a different PRIVATE_KEY. The original decryptor was dirty patched to use the same SIGN as was previously paid. We started the decryptor on the second infected machine, and all the data on the infected machine was decrypted! (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Successful decryption for spoofed PRIVATE_KEY.

Figure 10: Successful decryption for spoofed PRIVATE_KEY.

The Cerber authors simply did not perform a data integrity check, thus giving us the possibility to exploit this bug and decrypt machines with only one paid signature.

Figure 11: Data integrity check that authors have skipped.

Figure 11: Data integrity check that authors have skipped.

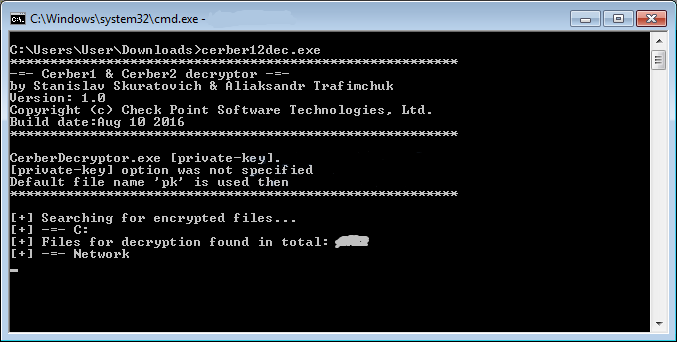

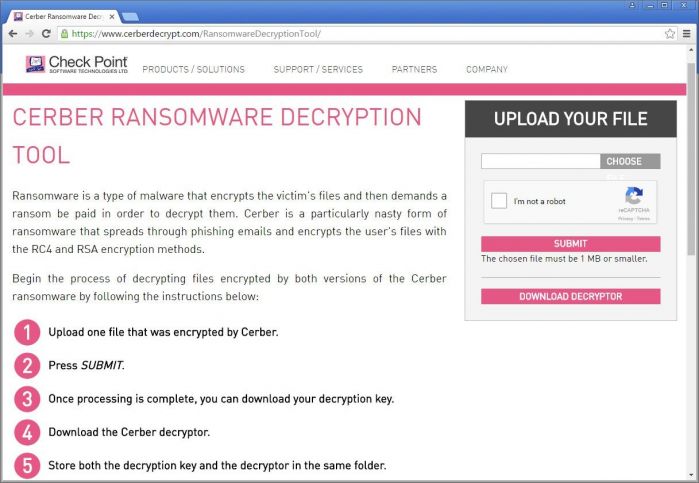

This section provides a general description of what actions were performed in order to establish a decryption service as soon as possible after the vulnerability was discovered. Our two main goals were to hide the flaw from the attackers for as long as possible and to make the bandwidth for decryption as wide as possible.

In order to fulfil both requirements we decided to set up a server that would be responsible for fetching the keys. After being fetched, the obtained key would be sent to the infected user. This key would then be used by the client-side decryptor to restore the files. Figure 12 provides an overview of the process.

Figure 12: Fetching decryption key for specific infection.

Figure 12: Fetching decryption key for specific infection.

The following steps are taken in order to retrieve the decryption key for a specific infection:

Figure 13: Infected machine decryption process.

Figure 13: Infected machine decryption process.

In order to parallelize victims' requests and reduce both the waiting time and server bug fixing, four decryption signatures were purchased. With that number of keys we were able to handle up to 20,000 decryption requests per day.

Figure 14: Check Point Cerber Ransomware Decryption Tool.

Figure 14: Check Point Cerber Ransomware Decryption Tool.

Now that we have examined the server-side flaw that gave us the chance to decrypt infected computers, let's take a look at the Cerber ecosystem and associated money laundering.

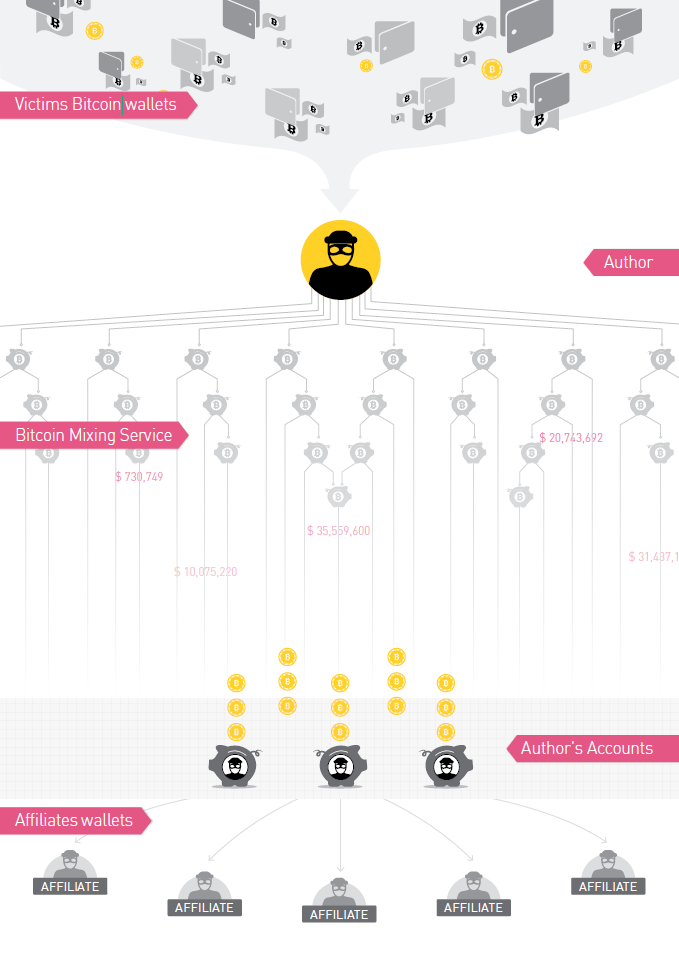

Cerber ransomware-as-a-service illustrates every aspect of an effective business franchise. The actor behind the operation, dubbed 'crbr', offers the ransomware for sale through a private, carefully managed affiliate program – actors who are willing to distribute the ransomware are granted a comprehensive use panel through which they can monitor the rate of the infections, encryption process and ransom payments. In return, 40% of the profits are transferred to 'crbr' as a fee. Based on data collected by our sensors, during July 2016 Cerber affiliates ran over 150 active campaigns, infecting nearly 150,000 victims, with a total estimated profit of US$195,000 per month, which adds up to US$2.3 million per year (the numbers are based on a Bitcoin conversion rate of US$590). In fact, the Cerber ransomware demonstrates a growth rate higher than that of major global fast food chains.

Figure 15: Cerber global distribution map.

Figure 15: Cerber global distribution map.

Cerber generates a unique Bitcoin wallet to receive funds from each victim. The generated wallet appears in the landing page shown to the victim, represented by an encoded string in the URL. Check Point researchers examined tens of thousands of victim Bitcoin wallets, and found that only 0.3% of the victims chose to pay the ransom. But the bigger question is: once a Bitcoin transaction occurs, what happens to the money? Based on our analysis, it seems that Cerber uses a Bitcoin mixing service as part of its money flow in order to remain untraceable. A mixing service allows the ransomware author to transfer Bitcoins and receive the same amount back to a wallet that cannot be associated with the original owner. This is achieved by mixing multiple users' funds together, using tens of thousands of Bitcoin wallets, making it almost impossible to track them individually (see Figure 16). Based on our research, automated tools distribute the affiliate shares only after the money has been swapped by the mixing service and the malware author's share has been collected.

Figure 16: Cerber Bitcoin flow.

Figure 16: Cerber Bitcoin flow.

Thousands of users restored their files while the Check Point Cerber Decryption Service was active. Unfortunately, the attackers were quite responsive and fixed the vulnerability within 24 hours.

Cerber ransomware-as-a-service uses a business model that has been proven to be effective by some of the biggest franchise businesses worldwide. Furthermore, the malware author uses a sophisticated money flow to ensure that the profits remain sealed and that its Bitcoin wallets cannot be associated with the attack operation. It is therefore little wonder that Cerber ransomware is one of the most widespread pieces of ransomware of our time.

We would like to thank the Check Point Malware Research and Threat Intelligence teams and in particular Aliaksandr Trafimchuk for his devoted help throughout the research.

[1] Cerber Decryptor. http://blog.trendmicro.com/trend-micro-ransomware-file-decryptor-updated/.

[2] Check Point Releases Working Decryptor for the Cerber Ransomware. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/check-point-releases-working-decryptor-for-the-cerber-ransomware/.

[3] Cerber 2 Ransomware: Free Decryption Tool Released. http://www.bankinfosecurity.com/cerber-2-ransomware-free-decryption-tool-released-a-9341.

[4] Cerber. http://blog.checkpoint.com/2016/08/16/cerberring/.

[5] Source code. https://github.com/CheckPointSW/CerberDecryptionService.

[6] RSA Factoring Challenge. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RSA_Factoring_Challenge.