Malwarebytes, USA

Malwarebytes, UK

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

Malicious advertising, a.k.a. malvertising, has evolved tremendously over the past few years to take a central place in some of today's largest web-based attacks. It is by far the tool of choice for attackers to reach the masses but also to target them with infinite precision and deliver such payloads as ransomware.

The complexity and layered structure of the ad industry has provided the perfect ground for rogue actors to game the system and create long-lasting campaigns that go almost unnoticed. Indeed, by using a combination of social engineering and technical tricks, fraudulent advertisers are able to enter ad platforms and push their malicious code.

While the debate about ad blockers continues to rage, malvertising will continue to make headlines for the foreseeable future – which is why it is important to stay up to date with its latest practices.

In this paper we will look at:

Malvertising regularly makes the news with some big name sites unwittingly exposing their visitors to malware because of malicious ad banners [1].

The term 'malvertising' was coined in 2007 [2], but the problem has been going on for more than a decade [3]. Over the years, the model has not changed much, in the sense that ad banners carried malicious code then and still do now. In fact, the ad tech industry has only become more complex and malvertising more prevalent.

In this paper, we take a quick – but necessary – look at some of the ad industry's basic concepts and explore in more detail where current business practices fall short.

We also show how malvertising, which can target multiple different platforms and take various shapes, is still largely misunderstood. For instance, according to a survey by botlab.io, 60% of people think that in order for an online advertisement to send malware, the user has to click on the ad first [4].

In the meantime, threat actors are taking on multiple identities and hiding their traces thanks to clever fingerprinting, enabling adverts to act as a direct gateway to exploit kits.

In this bleak context, we take a look at what the future of online ads may be like and how criminals will adapt in creative ways to keep milking the system.

In order to grasp why malvertising is such a profitable and efficient way to distribute malware, it is important to have a basic understanding of how the ad industry works.

As a malware researcher this may feel unnatural, but let's keep in mind that threat actors are savvy advertisers, albeit rogue ones, who have mastered the art of abusing the ad tech industry. Even a basic knowledge of the ad ecosystem really helps to track and guess the malvertisers' next move.

The ad industry is a complex and extremely powerful machine where automation, also known as programmatic, is key to allowing the buying and selling of ad space in real time.

Each time a user browses to a website (publisher), an auction takes place to display an advert (impression) that is customized for this particular user. This process, also known as Real Time Bidding (RTB), happens within milliseconds and is, of course, fully automated. Advertisers compete for each impression and the highest bidder typically wins the auction and gets to have its creative (the advert) displayed on the publisher's website.

Leveraging the depth of ad platforms, advertisers can precisely target potential customers by age, income, geolocation, operating system, and many more pieces of information which would likely frighten privacy-conscious users. Better targeting means better monetization downstream, which ironically is also true for the criminal enterprise.

One little known fact is how cheap advertising can be, especially when it is targeted effectively. This is measured by the CPM (cost per thousand impressions) and essentially means that an advertiser can display an ad banner to a thousand visitors for anywhere between a few cents and a few dollars.

While RTB is the basic concept upon which advertising relies, there are many other processes involved within the ad ecosystem that have grown out of an ever-evolving need to monetize Internet content. Often, security researchers will witness new incidents abusing something they haven't seen before, simply because the surface of attack is so large.

There are several ways threat actors can place a malicious advert but generally they fall into one of following scenarios:

The latter two are by far the most common because they do not require any type of hacking and instead leverage the inherent weaknesses of the ad ecosystem.

Table 1 shows the pros and cons of various practices observed in the ad industry. Please note that these greatly vary from one ad network or platform to the next and should not be generalized as the default standard.

| Practices | Pros | Cons |

| Ads automatically served in real time | No human interaction, fast and cheap | Lack of validation, attacks happen and are only stopped after the fact |

| Detailed user profiles | Companies get a greater return for their ad budget | Criminals can narrow down who their victims are |

| Billions of ad impressions | This an extremely lucrative industry | Volume brings complexity, attackers can hide in the noise |

| Third-party advertising, arbitrage | Flexibility for ad buyers, possibility of reselling for profit | Difficulty tracking who is serving what, and who takes responsibility |

| Self-serve platform | Easy and cheap to use | Very little oversight, huge risk for abuse |

| Easy sign-ups, low minimum budget required | Convenient for new advertisers, or those with low budgets | Fraudulent advertisers can easily get onto ad platforms and have little to lose if caught |

| Vetted partners | A vetted partner relationship helps both parties deal efficiently and trust each other | A vetted partner can still serve malware and the lack of scrutiny can actually backfire |

| Low CPM | Ability to target millions of users with relative cheap cost | Cost-effective method to infect scores of people |

| Rich content | Images, videos are and other types of animations make ads more engaging | Malicious code is more likely to be embedded in rich content, than a simple text-based advert |

| Third-party JavaScript tags, containers | Advertisers have better tracking mechanisms | Code can be swapped and allows for malicious injections |

| Self-hosted ad banners | Advertisers have complete control over the content they serve | The advertiser can be rogue or get hacked and serve malicious content directly |

Table 1: Pros and cons of practices observed in the ad industry.

To be fair, no industry is safe from criminal activity. To draw an analogy, credit card companies deal with fraud every single day and yet they are still thriving. However, unlike credit card corporations which can compensate customers for their losses, ad companies are not held liable for any damage to end-users resulting from malvertising attacks.

To make matters worse, there are practices that are known to be risky, such as arbitrage which involves buying ad space to eventually resell it to another (often less trusted or unknown) buyer. The reality is that there are economic incentives for ad tech players to keep engaging in certain practices despite the risks to end-users. The truth of the matter is that there is often very little validation of the identity of the advertisers who place ads, not to mention that they can easily pick up and start again as another entity.

The complexity and disparity in practices make the ad industry's business model ripe for abuse. Threat actors have understood those weaknesses and have been using them to their advantage while the industry struggles to redefine itself.

Whether referring to desktop or mobile-centric adverts, numerous half truths or plain misunderstandings related to how malvertising works potentially make rogue ads sound like less of a threat. Additionally, the notion that only people 'looking at porn' or torrents get caught by malverts, which may have been the case years ago, is no longer valid as major websites are serving rogue ads on a daily basis.

As mentioned earlier, one of the biggest issues with educating the public about malvertising is the misconception that the victim has to click the ad to become infected. The reality is that, more often than not, if the rogue ad has loaded then it's already too late and the PC is probably compromised.

The public may also believe that infections are over-hyped by security companies, as comments from site owners hit by malvertising typically include statements claiming that they received very few reports from disgruntled victims. However, the fact that many malverts work silently in the background, coupled with the expectation that a regular surfer is unaware of breaking malvertising developments, results in victims not actually knowing which site infected their PC in the first place.

Given that many 'legit' ads perform potentially obnoxious actions on the desktop (such as sliding into view, autoplaying sound, fading in as the surfer scrolls back up to the URL bar), it's particularly difficult to work out which ad will cause what problem – whether a minor inconvenience or a major malware infection.

There are so many ways bad actors can push malverts, it can be difficult to establish common traits or patterns to help identify specific groups. Small attacks relying on certain conditions (such as ignoring those running specific security tools) before launching to ensure they only target certain PC set-ups (and thus potentially flying under the radar) are just as valid an approach as the larger, 'fire and forget' attacks which see non‑discriminatory exploits launching malware at victims' PCs from dozens of major web publishers simultaneously.

In both scenarios, the likelihood of the bad actors being caught by law enforcement is remote, given the ease with which fake credentials can be used to set up advertising accounts – a problem which has existed going back to the days of major adware players such as Zango and Direct Revenue, who would typically place all blame on rogue affiliates spiralling out of control [5].

Embedded ads in toolbars – or even just an endless stream of ad redirects via browser extensions – can cause major headaches for surfers, as well as potentially making it more difficult to track the source of an infection.

In February 2016, a toolbar possessed the capability to inject its own ad banners into web pages, and a rogue ad injected into the page resulted in a compromise attempt. The rogue advertiser would fingerprint the victim to ensure they wanted to infect them, then made use of redirection to an Angler Exploit Kit drive-by attempt [6].

While much of the appeal where malvertising is concerned is the automated nature of exploits and installs requiring little (if not zero) human interaction, many bad actors dabbling in adverts rely on a combination of PUPs and social engineering to make their ill-gotten gains.

One of the most popular tactics is the ever popular install bundler, sometimes classed as a 'Download manager'. Ten years ago, these were adware bundlers – nowadays, they're more likely to be the (theoretically) tamer PUP (Potentially Unwanted Program) download managers. The end result is the same: multiple installs of programs generally unrelated to what the victim was originally looking for, links to scammy adverts selected by geolocation, and a variety of fake 'Your browser/Java/Flash/video player is outdated' prompts [7].

Whether tied to bundled installers or not, many fake 'outdated program' advert landing pages end up leading to malware.

While the above is a crude – if successful – technique, there are occasional splashes of sophistication buried among the rather basic confidence tricks.

In June 2016, we saw a fake LastPass extension in the Chrome store which set victims on a journey of multiple install pages, additional extension install prompts, and websites harbouring numerous 'Install now' buttons. Often these install prompts are designed to mimic the look and feel of the current site, leading to unwanted installs/adverts – while the download link you actually want is buried in small text elsewhere on the page [8]. Google's Safe Browsing has started cracking down on techniques such as this, classing them as social engineering [9].

Mobile lives or dies on its ability to be convenient, whether browsing or performing common tasks. The desire to pay instantly without the need for sign‑ups or entering payment details has given rise to so-called 'Direct to bill', where a click of the payment button bills your network provider, with the cost being passed to you via your bill [10].

While these services are supposed to have a specific flow in order to prevent dubious behaviour, the reality is that the merchants (website owners) find ways to subvert the process and trigger a payment state without anything being pressed on the landing site.

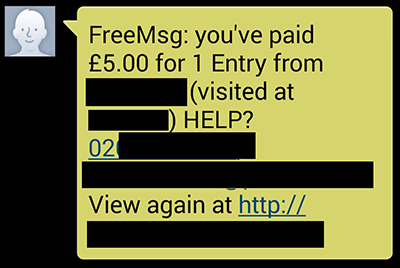

When browsing an otherwise benign website, advert redirects targeting mobile users would send victims to an apparently blank page. At this point, the device owner would receive a text message informing them that they'd paid £5 to enter a lottery, with a 'view again' message attached (which would potentially result in another payment being made if clicked). Although there is a maximum limit on payment amounts for these services (so it isn't possible to lose large sums of money), the recovery process is so convoluted that scammers stand to make large sums of money from victims who give up on ever regaining their cash.

Figure 1: Text message informing the device owner they have entered a lottery.

Mobile networks ask victims to contact merchants directly and raise a complaint – in practice, this means victims have to contact the scammer, hand over personal information to (in theory) receive a cheque and then hope the scammers don't try something else with the newly obtained PII. As most (if not all) of these services rely on premium services being available on a mobile, one of the only ways to avoid charges besides using a mobile ad blocker is to disable premium billing. Unfortunately, most mobile networks enable premium numbers by default on the basis that customers may want to use these services, so lengthy calls to carriers may ensue to switch it off.

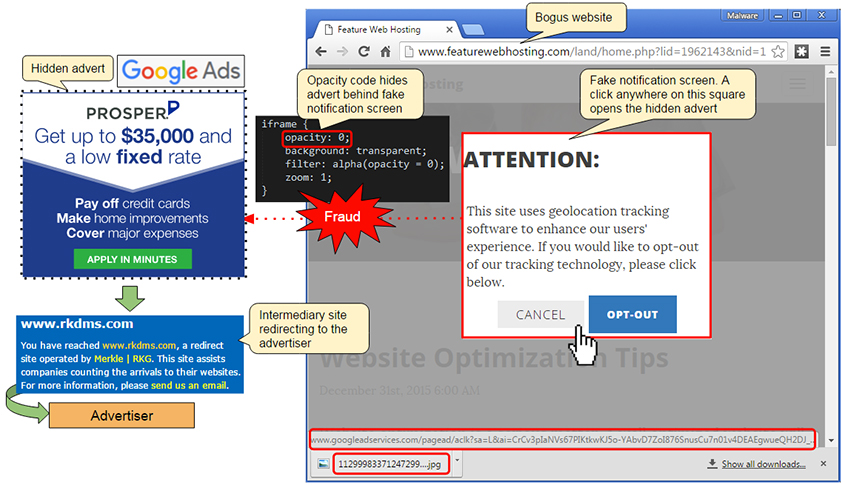

Laws and regulations intended to keep us safe or aware of different types of PII collection are, in some cases, contributing to rogue installs by retraining us to take risky actions online. An EU directive resulted in all affected countries updating their privacy laws [11], so in most cases a website will notify you of their cookie policy. In practice, this means millions of people rush to click an 'OK' prompt to remove it from the screen and go about their business.

Scammers have exploited this by placing an invisible iframe ad over the top of a cookie tracking style pop‑up – the moment the supposed warning box is clicked, the victim loads the advertiser's website and a profit is made via clickjacking [12].

Figure 2: Clickjacking.

As the name suggests, malware is the end-game for malvertising and at present nothing comes close to the headaches posed by ransomware drive-bys. There are numerous instances of ransomware being dropped onto both mobiles and desktops – in some cases riding a wave of dubious privacy invasions [13], and in others trying to sneak past detection while pushing large campaigns out to hugely popular websites across the globe [14].

In the latter example, the bad actors had planned ahead – making use of domains registered many years ago and purchasing 'clean' ads so as not to raise suspicions, then striking after attracting precisely zero negative attention. Many of the groups behind these scams are in it for the long haul, and are suitably difficult to weed out as a result.

As advertising evolves, so do malvertising attacks. New mediums such as video adverts are now also being abused to serve malware [15]. The problem with video ads is the possibility of embedding third-party code at various levels, weakening any trust one may have in the VAST and VPAID formats.

The major malvertising attacks always seem to come out of nowhere, leaving many dumbfounded. Threat actors love to create fake online identities and leverage various tools and techniques to blend in while they hide their malicious intent.

Trust is a critical factor in any kind of transaction or business. In advertising, trust is extremely important, especially when the stakes are high (i.e. top publishers with millions of visits).

A fraudulent advertiser wants to gain access to these large audiences to get maximum exposure for his payload. In some cases, as mentioned earlier, criminals will hack legitimate – and trusted – buyers and hijack their account to accomplish their nefarious purposes. In other cases, fraudsters only need to dupe someone that is already trusted within the ad chain to avoid having to go through more extensive security screening themselves.

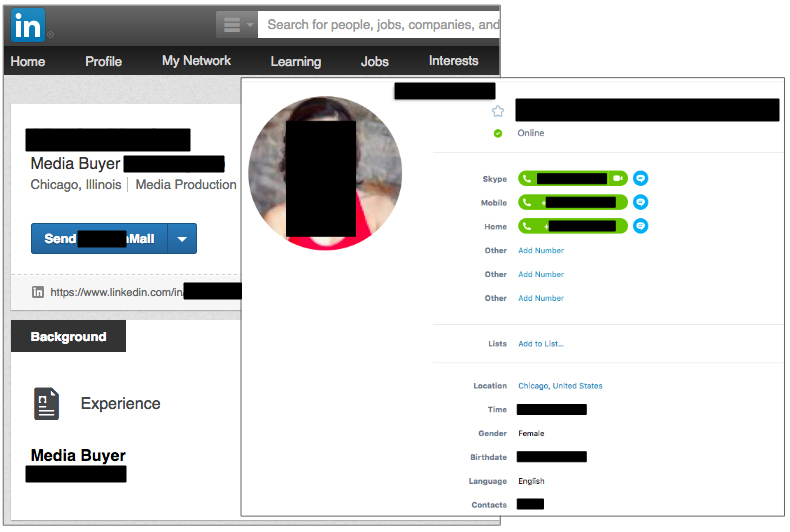

Rogue actors were born to create various profiles, websites and other online presence indicators out of thin air or by stealing material from someone else. With a basic fake identity that can consist of a LinkedIn profile and Skype account, the assumed advertiser is ready to go and spend some ad money and push clean ads for a little while to avoid any suspicion, before eventually starting to slowly disseminate rogue ones.

Figure 3: Fraudulent advertiser.

By playing this game of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, rogue advertisers can remain undetected for long periods of time.

Domain shadowing is an extension of the fake identity which further contributes to hide the perpetrators behind what is essentially a smoke screen.

Domain shadowing is the creation of subdomains via stolen registrant account credentials for malicious purposes. Exploit kits such as Angler have made this technique popular because of its unique way of evading blacklists [16].

Rogue advertisers leverage domain shadowing to steal an existing company's identity, as well as host the ad banner and malicious code on their own server.

They start by finding several potential victims, typically using website account credentials harvested via phishing emails or malware. The crooks then create a subdomain that points to their own server, often leveraging the privacy features of cloud providers to add another layer of deception.

This server hosts various files associated with the advert, which include some JavaScript and the ad banner itself. The image is made hastily from logos and text stolen from the website of the company the crooks are impersonating, but to all intents and purposes it looks genuine.

During our research we were able to link several different malvertising incidents based on metadata from the ad banners themselves, showing that the same group was behind all these attacks [17].

The abuse of free SSL providers is often a dead giveaway that a subdomain does not belong to the website owner when their main domain is still plain HTTP [18] or uses a different certificate.

While 'HTTPS everywhere' is a good thing for security as a whole, it poses some challenges for researchers and existing monitoring tools. This is especially true when ad banners are served from the advertisers' own servers, where all of a sudden all of the code is wrapped in an encrypted tunnel and invisible to security solutions placed between the ad server and the client (browser).

It also becomes more difficult for attributing and reporting incidents [19] because not only is the ad content encrypted but so is the ad call URL. Typically, such URLs contain various identifiers for the publisher, advertiser and campaign ID which can really help to narrow down the perpetrators.

Online crooks very much leverage the profiling available to all advertisers via ad platforms to target certain countries, and even types of users, with great precision. While criminal 'traffers' were already very good at distributing traffic based on various selectors, they cannot beat the power of the online ad industry when it comes to 'knowing your audience'.

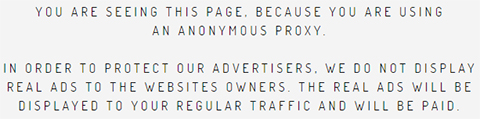

The quality and relevance of traffic that matters so much to advertisers is also critically important to malware distributors. The latter benefit from the ad network's potential ability to distinguish real traffic versus bots or VPNs, so that the intended victims are genuine users.

Figure 4: VPN detection.

In the more advanced malvertising cases, the targeting is such that trying to reproduce an attack 'artificially' in a lab environment will often not yield any results. Threat actors have the upper hand when it comes to switching attacks on and off at the time of day and time zone of their liking, not to mention a plethora of other criteria.

Fingerprinting is an interesting concept which aims at discarding unwanted users by leveraging information disclosure bugs on the client side, typically in the browser.

It adds yet another layer of filtering, which threat actors use to guarantee honeypots, and security scanners only see benign activity instead of getting the intended malware payload.

A vulnerability in Internet Explorer's XMLDOM ActiveX control (CVE-2013-7331) [20] allows attackers to enumerate the local file system and look for certain file and folder names. Examples include looking for anti-malware and anti-virus software.

Figure 5: Filename enumeration.

Another bug with the MIME type check [21] also allows it to be determined whether a file extension is associated with a program, directly from the web browser. By finding out that the .pcap extension is associated with a program, attackers know that the current user is most likely a security researcher running the Wireshark network protocol analyser.

Exploit kits have long used fingerprinting in their landing pages [22] to quickly detect the presence of virtual machines, traffic packet capture and web debugging software, as well as security products, and to make the decision to abort the exploits and payloads.

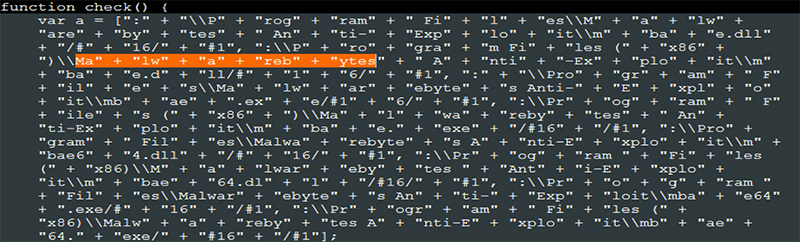

Figure 6: Encoded fingerprinting.

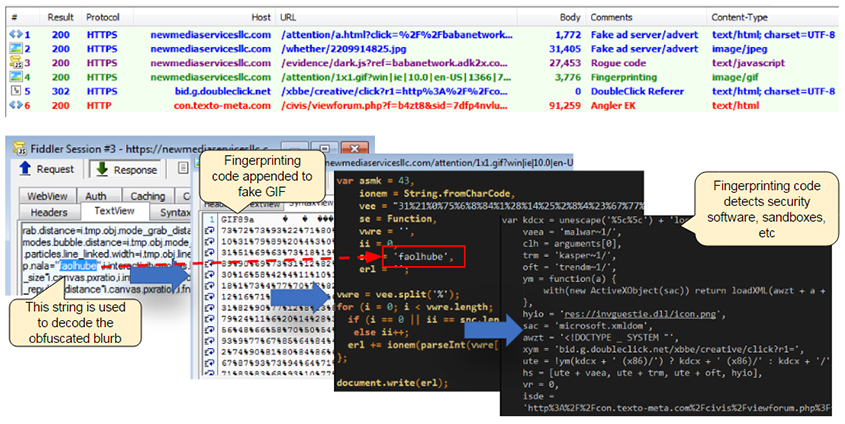

Threat actors realized that they could move or at least duplicate the fingerprinting earlier in the attack chain and that by placing it within the ad banner they could filter – and more importantly discard – non intended victims, who would never see the exploit kit. The benefits are less unwanted traffic, more precise targeting, and of course lack of any evidence from an ad-check point of view.

Malwarebytes and GeoEdge described this technique in a joint research paper entitled 'Operation Fingerprint' [23], which detailed sophisticated new ways to perform these checks away from prying eyes.

Back in the summer of 2015, we were stumped while investigating several high-profile malvertising cases, trying to find what some in the industry call the 'smoking gun'. In other words, without actual proof of a direct connection between an advertiser and malicious code, one simply cannot accuse the former of any wrongdoing.

It took hours of painstaking work to be able to reproduce and spot what we would later call fingerprinting. That code was hiding, in plain sight so to speak, within a GIF image. What gave it away was its larger than normal size for a 1x1 pixel tracker since it had embedded JavaScript code in it.

In later variants of the fake GIF attacks, threat actors added obfuscation to the fingerprinting code, which in some cases required a key to decode. That key was a string of characters cleverly planted in between a large JavaScript file, making identification more difficult.

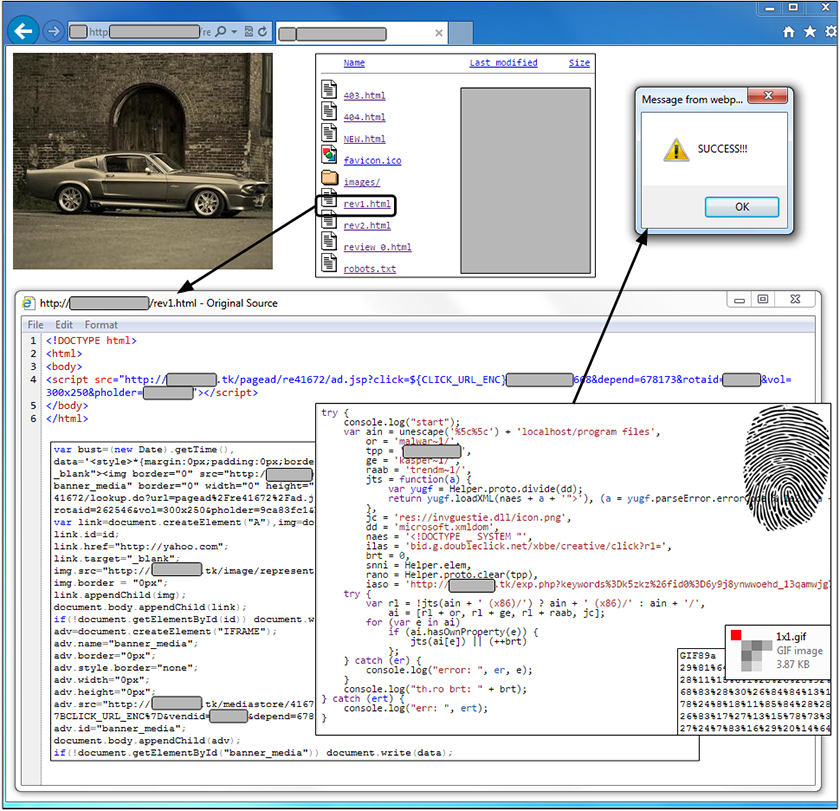

During some research into a particular campaign, we stumbled upon an open web server that was used to test the fingerprinting technique. The code contained a few extra lines to output the results to the console and displayed a 'success' alert box if the detection routine worked. Observing the malware authors refine their tool almost in real time was a troubling experience.

Figure 7: A 'success' alert is displayed if the detection routine works.

Targeting users precisely is not only a way to maximize infection rates but also a means to fly under the radar by limiting unnecessary exposure. The combination of exploits and profiling tools from the ad industry gives threat actors a unique advantage which they leverage against the very same people that try to stop them.

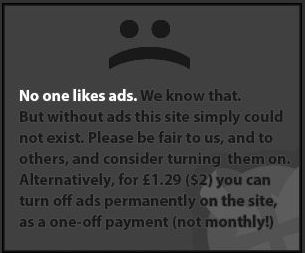

Browsing the web is becoming an increasingly schizophrenic activity. With an ad blocker installed, it's not uncommon for a site to trigger two messages to the surfer simultaneously – one which asks them to switch off their ad blocker, and one from the ad blocker itself which asks if they'd like to switch off the messages from the site asking them to unblock the ads.

Figure 8: A plea to turn off ad blockers.

This becomes even more confusing when people release so-called ad blocker blocker blockers, designed to prevent sites noticing the installed ad blocking tech and let the surfer continue browsing as normal. Many of these tools turn out to be rogue or simply don't work, which further muddies the waters.

Ad blocking analytic firms who provide blocking stats to webmasters have also been compromised, such as PageFair (whose account on a content distribution network was hijacked in 2015) and used to push a fake Adobe Flash update, which was served by 501 publishers in 83 minutes [24].

Ultimately, all of these compromises eventually hurt the websites that find all of their ads blocked by default – recent studies have found that one in five smartphone users block advertisements [25], and even console gamers have been blocking dynamically served ads for many years – in 2011, Xbox users were using OpenDNS to block ads served on their console dashboard [26].

A new trend in advergaming – which is when an advert is displayed in a videogame – replaces passive background banners and pop‑ups (which can all be worked around) with adverts that are an integral component of gameplay itself. When a gamer is about to die, the game pauses and a message appears on the screen, reading: 'You're about to die, want to be saved by viewing an ad? [Yes! Save me!] [No, let me die].' This approach seeks to reduce or even eliminate ad removal by using techniques which would potentially break the game if such a thing was attempted. We expect to see this increasing in popularity as more people look to eliminate ads from their daily experiences.

Blurring the lines further, what we call 'online' is moving into the world around us, and as a result, forms of online advertising and tracking are following the same path. Ad companies want to make use of near field communications to combine location‑based video and mobile to 'watermark' mobiles when they pass specific digital screens – at which point, a relevant advertisement is served to the mobile device [27].

Depending on how these services are deployed by companies around the world, there may be different forms of consent required before a service can be used, and ultimately it may be too much hard work for a shopper to understand – at which point, they simply switch off their phone and are no longer reachable.

While some may not be troubled by online ads, the people who feel real‑world interaction is a step too far and intentionally make themselves unreachable by friends or family just to skip ads are having a demonstrably negative impact on their life as a result.

On a similar note, while the real‑world impact of so-called public shaming on social networks is a hotly contested practice, in 2015 real‑world advertising took this social media phenomenon into the streets of Hong Kong. A marketing communications agency teamed up with a nano-pharmaceutical company to create accurate so-called 'Wanted' posters built from the DNA of people dropping litter [28].

While the concept is an interesting one, there is room for error – what if the litter was in the streets because of a ripped trash bag? What if someone had dropped it accidentally or it had fallen out of their pocket? Again, we see the potential for advertising in the world around us to have a prominent detrimental impact on an individual's life.

Technologists are busy building real‑world ad blockers, which mount on headsets and attempt to blur out any and all brands and logos as you see them on your day‑to‑day travels [29]. How long will it be before the more traditional forms of online ad blocking – which attempt to filter out networks and tracking – also make the leap, taking on everything from mall ads to DNA-centric billboards?

And, more importantly, will the real world become as schizophrenic as the online model as a result?

Whatever move site owners and publishers make next, the reality is that ad blocking is here to stay. Slowly but surely, we're seeing major websites setting up tools to report bad ads. In 2016, popular modding site Nexus Mods implemented an advert reporting service, and in two months, they received more than 8,500 reports on 115 specific ad placements [30]. As a result, they changed to another ad network.

Similar things are happening on other major sites such as Neogaf [31] – interestingly, these attempts to curb rogue ads are coming from the gaming sector. While some webmasters are beginning to realize the negative impact bad ads can have on their ability to make money, it may well be that blocking ads is more of a band aid than a permanent fix.

The ad model currently in place, with banners and boxes placed onto websites – which is mostly unchanged from the way it was a decade ago – may simply be one which was never meant to have a long shelf life. With its multiple moving parts and endless chains of potentially bad actors, it's certainly not conducive to security practices, with a never ending stream of compromises as a result.

'Tip jar'-style funding along the lines of Patreon/Kickstarter, or simply paying a one‑off/repeating fee to hide ads or provide additional services over non-paying customers may be the way forward. The difficulty is in convincing enough visitors to hand over the money in the first place – without this, we're likely going to be stuck with the current, arguably broken by default model we have.

[1] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Labs. Large Angler Malvertising Campaign Hits Top Publishers.

https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2016/03/large-angler-malvertising-campaign-hits-top-publishers/.

[2] Salusky, W. InfoSec Handlers Diary Blog. Malvertising. https://isc.sans.edu/diary/Malvertising/3727.

[3] Liston, T. InfoSec Handlers Diary Blog. https://isc.sans.edu/diary.html?date=2004-07-23.

[4] Kotila, M. botlab.io. Busting Malvertising Myths –The Role of Adtech Industry in Malvertising.

http://botlab.io/busting-malvertising-myths-the-role-of-adtech-industry-in-malvertising/.

[5] Edelman, B. People of the State of New York V. Direct Revenue, LLC. http://www.benedelman.org/spyware/nyag-dr/.

[6] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Labs. Wajam browser Add-on serves Malvertising. https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2016/02/wajam-browser-add-on-serves-malvertising/.

[7] Artnz, P. Malwarebytes Labs. AdLoad: an advertisement bombarder. https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2016/04/adload-an-advertisement-bombarder/.

[8] Umawing, J. Malwarebytes Labs. Fake LastPass extension exposes users to ads and installs.

https://blog.malwarebytes.org/cybercrime/2016/04/fake-lastpass-extension-exposes-users-to-ads-and-installs/.

[9] Google Security Blog. No more deceptive download buttons. https://security.googleblog.com/2016/02/no-more-deceptive-download-buttons.html.

[10] Boyd, C. Malwarebytes Labs. Watch out for costly mobile ads. https://blog.malwarebytes.org/cybercrime/2015/08/watch-out-for-costly-mobile-ads/.

[11] European. Commission. Cookies. http://ec.europa.eu/ipg/basics/legal/cookies/index_en.htm#section_2.

[12] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Labs. Clickjacking campaign plays on European cookie law.

https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2016/01/clickjacking-campaign-plays-on-european-cookie-law/.

[13] Boyd, C. Malwarebytes Labs. Malvertisements on "Fappening" forum lead to Android Ransomware.

https://blog.malwarebytes.org/cybercrime/2016/04/malvertisements-on-fappening-forum-lead-to-android-ransomware/.

[14] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Labs. Malvertising Campaign Goes (Almost) Undetected. https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2015/09/large-malvertising-campaign-goes-almost-undetected/.

[15] Dangu, J. Malwarebytes Labs. Video Ads: Malvertising's Next Frontier? https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2015/11/video-ads-malvertisings-next-frontier/.

[16] Talos Group. Threat Spotlight: Angler Lurking in the Domain Shadows. http://blogs.cisco.com/security/talos/angler-domain-shadowing.

[17] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Labs. A Look Into Malvertising Attacks Targeting The UK.

https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2016/03/a-look-into-malvertising-attacks-targeting-the-uk/.

[18] Proofpoint Staff. The shadow knows: Malvertising campaigns use domain shadowing to pull in Angler EK.

https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/The-Shadow-Knows.

[19] Franceschi-Bicchierai, L. Motherboard. The Downside of Encrypting Everything: Virus-Filled Ads Are Harder to Track. http://motherboard.vice.com/read/the-downside-of-encrypting-everything-virus-filled-ads-are-harder-to-track.

[20] National Vulnerability Database. Vulnerability Summary for CVE-2013-7331. https://web.nvd.nist.gov/view/vuln/detail?vulnId=CVE-2013-7331.

[21] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Labs. The proof is in the cookie. https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2014/11/the-proof-is-in-the-cookie/.

[22] Kafeine. MalwareDontNeedCoffee. CVE-2013-7331/CVE-2015-2413 (onload variant) and Exploit Kits.

http://malware.dontneedcoffee.com/2014/10/cve-2013-7331-and-exploit-kits.html.

[23] Segura J.; Aseev, E. Operation Fingerprint: A Look Into Several Angler Exploit Kit Malvertising Campaigns.

https://blog.malwarebytes.org/threat-analysis/2016/03/ofp/.

[24] Martin, A. Anti-adblocker firm PageFair's users hit by fake Flash update. The Register.

http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/11/02/pagefair_malware_snare_scare_in_halloween_hack_of_adblocker_blocker/.

[25] Ungureanu, H. Mobile ad blocking surge: 1 in 5 smartphone users block ads on their device: report. TechTimes. http://www.techtimes.com/articles/162128/20160531/mobile-ad-blocking-surge-1-in-5-smartphone-users-block-ads-on-their-device-report.htm.

[26] Absurdlyobfuscated, Reddit. How to block Xbox dashboard ads. https://www.reddit.com/r/gaming/comments/n5831/how_to_block_xbox_dashboard_ads/.

[27] Screen Media daily. Location based mobile ads coming to mall screens nationwide. http://screenmediadaily.com/location-based-mobile-ads-coming-to-mall-screens-nationwide/.

[28] S. C. M. Post. Hong Kong litterbugs shamed in billboard portraits made using DNA from trash.

http://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/article/1804420/hong-kong-litterbugs-shamed-billboard-portraits-made-using-dna-trash.

[29] Vanhemert, K. Wired. An AR experiment that works like an ad blocker for real life. http://www.wired.com/2015/01/adblock-real-life-adblock-real-life/.

[30] Boyd, C. Malwarebytes Labs. Nexus mods site goes public with "bad ad" report. https://blog.malwarebytes.org/cybercrime/2016/05/nexus-mods-site-goes-public-with-bad-ad-report/.

[31] EviLore. NeoGAF ad quality improvement/monitoring and user reporting functionality now live. http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=1229205.