Symantec, India

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

Since last year, there has been growing interest in a technique known as fileless infection, where malware authors compromise computers without writing any files to disk. This technique allows the threat to evade detection by file-scanning software while still remaining persistent.

This paper will explain the different fileless infection methods, as well as a new tactic that could allow attackers to perform fileless infection through a classic one-click fraud attack using non-PE files.

Traditional malware is contained in a file on disk. A registry run key links to this file in order to make the threat persistent. With fileless infection, the malware does not exist on the compromised computer as a normal file. Instead, it is located in a subkey within the computer's registry as a script, such as Windows PowerShell, VBScript, or JavaScript. The payload in the registry is called every time Windows starts.

The one-click fileless infection technique we've seen uses JavaScript, though different scripts could also work. The infection arrives on the computer through an .hta file, which places the JavaScript payload into a registry subkey. The JavaScript code can be triggered every time Windows starts by calling the following:

rundll32.exe javascript:"\..\mshtml,RunHTMLApplication ";alert('payload');

The JavaScript code can read and decode encoded data from another subkey. This data injects the payload into memory. Every few minutes, the payload checks for its registry entry. If the entry has been deleted, the payload recreates it so that the infection remains persistent.

The first widespread threat we saw using the fileless infection technique was Trojan.Poweliks [1] in 2014. Many other trojans followed suit as they evolved, just two of which are Trojan.Bedep [2] and Trojan.Kotver [3].

Our paper will explain and compare the most common ways in which malware authors use fileless infections today. We will discuss areas where we expect these methods to be used in the near future.

Traditionally, AV products detect malicious files using strings or code signatures found in the file. Malware has several ways to avoid being detected, one of which is to put only the malicious code in memory. One example is Korplug, where the infection chain includes the decryption of an encrypted file, which is an executable file loaded in memory [4]. It does this so that the code is protected when an AV product scans the file. A fileless type of infection does this on a different level – there is no longer a file written to disk for the AV product to scan. Even if the file is not on the disk, the malware must still have a persistence mechanism.

The first fileless malware that caught the attention of researchers is Trojan.Poweliks, discovered in 2014. Poweliks does not exist as a file on a disk, but instead resides in the registry, which it only uses as a persistence mechanism [5]. Poweliks uses a special naming scheme to hide in the registry and has consistently used CLSID hijacking as runtime load point in the registry. Later on, Poweliks was also observed exploiting the Microsoft Windows Remote Privilege Escalation Vulnerability (CVE-2015-0016) [6] in order to take control of compromised sites. At the same time, another fileless malware, Trojan.Bedep, was also using the same zero-day exploit. Bedep is an in-memory-only downloader and perceived to have a similar coding style to Poweliks. Trojans like Trojan.Bedep and Trojan.Kotver have learned from Poweliks and adopted the same technique.

Typically, fileless malware arrives through exploit kits (EK) when a user visits a compromised site. The Angler exploit kit was the very first EK observed to infect a host without writing the malware on the drive [7]. The shellcode delivered by Angler is responsible for injecting the fileless malware into the process running the exploited plug-in, such as iexplore.exe. Fileless malware may also arrive through malicious file attachments or malicious URL links found in spammed emails. These are usually downloader malware, which are first written over the disk but eventually delete themselves after injecting the fileless malware into memory.

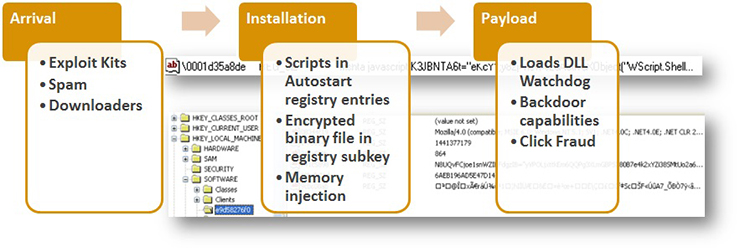

Figure 1: Infection chain of fileless threat.

Figure 1: Infection chain of fileless threat.

Once injected into the memory, the malware loads and encrypts a binary component. This obfuscated copy is saved in the registry and then another entry is created. This contains the script as part of its autostart mechanism. This script can be either VBScript, JavaScript or PowerShell script, and is responsible for decrypting the binary component and loading it into the memory.

The binary component is then launched and serves as a watchdog – it monitors the relevant registry entries it created and is also responsible for contacting the malicious command and control (C&C) server. Back door capabilities of this malware may include reinstalling registry entries, downloading and executing files, and calling other commands. One of the files it downloads and executes can install an ad-click module into memory.

From the file-based malware known as Wowliks, Trojan.Poweliks evolved into a registry-based malware. One of its notable behaviours is downloading a PowerShell application, hence the name Poweliks. This malware uses PowerShell scripts to launch and inject its DLL watchdog from the registry entry into the DLLHost.exe process to retain its persistence mechanism. The main payload of Poweliks is to deliver ad-fraud trojans and ransomware to the infected user.

Trojan.Bedep is believed to have a connection to Poweliks due to similarities in coding style and the use of the same CVE-2015-0016 exploit, but there is no conclusive evidence linking the authors of the two pieces of malware. Bedep has been observed to download and install Poweliks along with other ad-fraud malware. Bedep comes in 32-bit and 64-bit variants and uses Microsoft properties for its own file properties as part of its disguise. The main purpose of this malware is to turn the compromised computers into botnets.

Prior to adopting Poweliks's fileless infection technique, variants of the Kotver malware were residing only in the registry to evade detection. However, it does not fully embrace the fileless infection technique. Like Poweliks, it downloads a PowerShell application, but if no Internet connection is available, it reverts to file-based infection and creates a copy of itself on the disk. Kotver has been observed to deliver ransomware and banking trojans.

There has been growing interest in fileless infections over the last couple of years. Earlier, we explained the different infection vectors used by different actors. Now, we will discuss a new infection vector, which can potentially be used for performing fileless infections with non-PE files, using a classic one-click fraud attack method [8].

First, we will discuss all the individual components one by one, making it easy to understand one-click fileless infection.

This program is an implementation of the WebBrowser control that runs trusted HTML and scripts with a minimal user interface (UI).

As technology improves and grows with time, some of it does deprecate. In Windows OS, one such powerful technology has existed since Windows NT (released in July 1993) and is still present in Windows 10 (released in July 2015): HTML Application (HTA).

HTA [9] is a Microsoft Windows program whose source code consists of HTML, Dynamic HTML, and one or more scripting languages supported by Internet Explorer (IE), such as VBScript or JScript. The HTML is used to generate the user interface, and the scripting language is used for the program logic. An HTA executes without the constraints of the Internet browser security model; in fact, it executes as a 'fully trusted' application. The usual file extension of an HTA is .hta.

All the current Windows OSes support HTA file execution. HTA looks and behaves like an HTML file, but it has much higher privileges than an HTML file. An HTA file requires mshta.exe, which comes along with Internet Explorer. Mshta.exe executes the HTA by instantiating the Internet Explorer rendering engine (mshtml) as well as any required language engines (such as vbscript.dll).

HTAs provide a way for users to wrap scripts up in a graphical user interface (GUI), an interface replete with check boxes, radio buttons, drop-down lists, and other Windows elements.

For our purposes, an HTA is nothing more than a way to provide a GUI for scripts. As we have already noted, neither WSH nor VBScript provides much in the way of GUI elements: no check boxes, no list boxes, nothing. Internet Explorer, however, makes use of all of these elements and more. Because an HTA leverages IE, a user can take advantage of all these GUI elements when writing system administration scripts.

How closely related are HTML files and HTAs? All a user has to do is take any HTML file and change the file extension from .htm (or .html) to .hta, and just like that, the file is now an HTA.

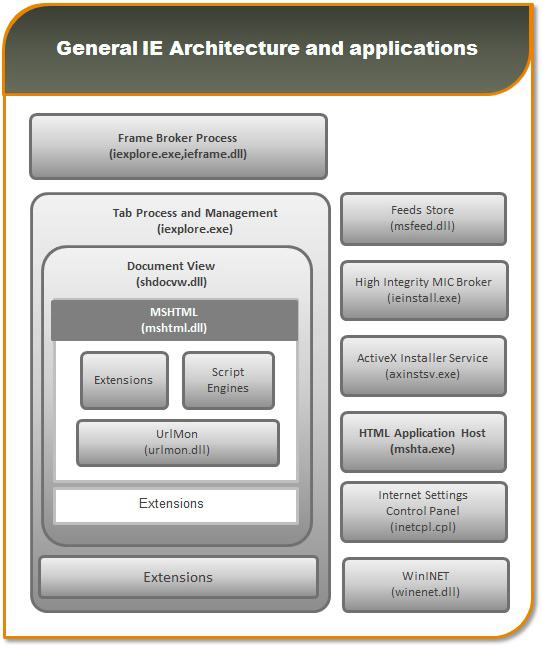

Figure 2: General IE architecture and applications [10].

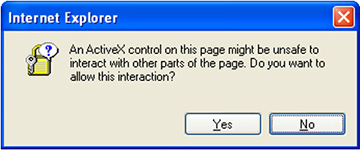

The very simple answer is: security. There are a lot of security restrictions implemented on IE, and for good reason: if users visit a website they would probably prefer that the site does not use a client-side script that starts reconfiguring their settings or rooting around in their file system. Consequently, many system administration scripts – including those that use WMI or ADSI – either will fail when run from IE or, at best, will display a dialog box similar to the following:

Figure 3: A dialog box is displayed whenever users run scripts from an HTML file.

Whenever users run scripts from an HTML file they are presented with a dialog box like this. That might be okay, but it is definitely not the best possible user experience.

HTAs, by contrast, are not bound by the same security restrictions as IE, because HTAs run in a different process from IE. HTAs run in the mshta.exe process rather than the iexplore.exe process. Unlike HTML pages, HTAs can run client‑side scripts and they have access to the file system. Among other things, this means that HTAs can run users' system administration scripts, including those that use WMI and ADSI. The users' scripts will run just fine, and they will not receive any warnings about items that might be unsafe.

Of course, this does not mean that HTAs somehow bypass Windows security. For example, if one user does not have the right to change another user's password, then the former cannot use a script to change the latter's password. Placing that script in an HTA will not make a difference – the user still will not be able to change the other user's password. HTAs also have some security restrictions of their own.

The long and the short of it is that, although HTAs use Internet Explorer and the IE object model, they run in a different process from IE. Consequently, users can run scripts and perform other tasks that are not allowed in IE.

More information about HTAs and security can be found on the HTML Applications SDK page [11] on the Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN).

When a regular HTML file is executed, the execution is confined to the security model of the web browser – that is, it is confined to communicating with the server, manipulating the page's object model (usually to validate forms and/or create interesting visual effects) and reading or writing cookies.

On the other hand, an HTA runs as a fully trusted application and therefore has more privileges than a normal HTML file; for example, an HTA can create, edit and remove files and registry entries. Although HTAs run in this 'trusted' environment, querying Active Directory can be subject to Internet Explorer Zone logic and associated error messages.

After analysing file infections and their infection vectors, we discovered that infections are also possible if attackers use non-PE files and a very well-known infection vector: one-click fraud.

One-click fraud is not new; it has existed for over a decade and has been seen affecting mostly Asian countries, most notably Japan. Typically, one-click fraudsters attempt to trick users into subscribing to bogus adult video services with a single click, although variants requiring two, three, and four clicks – even zero clicks – have also been observed [12]. One-click fraud exhibits ransomware-like behaviour, in that it attempts to lock the user's screen and create non-terminating or recurring pop-up windows, which ask the user to register, subscribe, or pay a certain amount to remove them.

We found that malicious actors could potentially mix fileless infection and one-click fraud to create one-click fileless infection. In a nutshell:

Fileless infection + one-click fraud = One-click fileless infection

We used an HTA file to create an ActiveX object that could inject the JS payload into a Run registry entry. We found that the same can be achieved using PowerShell and WSCRIPT (VBS).

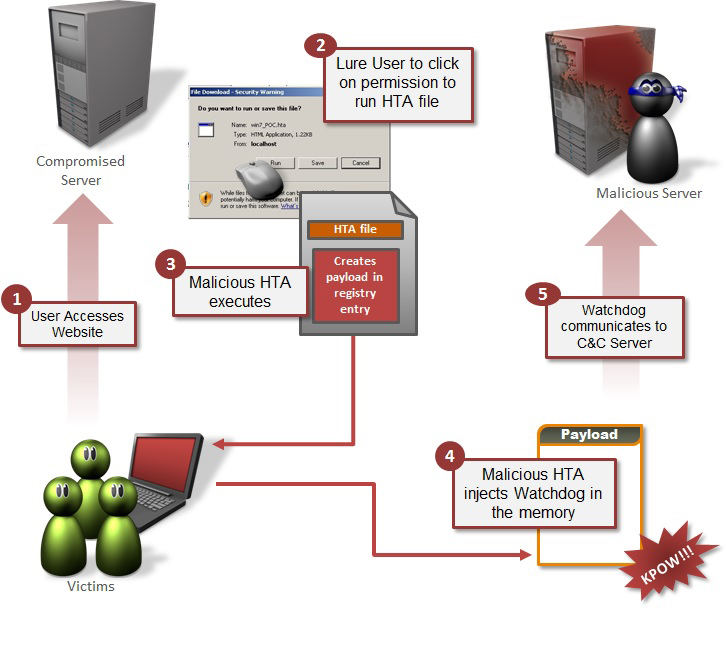

Figure 4: How the attack works.

The code shown in Figure 5 is for the HTA file, which could be hosted on an attacker's controlled server. In an infection scenario, the user is enticed to visit the website (using social engineering or a watering hole attack), and then asked to click Run/Execute. Once executed, the file creates a WScript ActiveX object, which then creates the Run registry entry and injects it with a JS alert (for POC) which is executed using rundll32.

/****************************POC*********************************************/

<html>

<head>

<title>RegTest</title>

<script language="JavaScript">

function writeInRegistry(sRegEntry, sRegValue)

{

var regpath = "HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\\SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run\\" + sRegEntry;

var oWSS = new ActiveXObject("WScript.Shell");

oWSS.RegWrite(regpath, sRegValue, "REG_SZ");

}

function readFromRegistry(sRegEntry)

{

var regpath = "HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\\SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run\\" + sRegEntry; /*Payload injected in Run registry entry*/

var oWSS = new ActiveXObject("WScript.Shell"); /*WASCRIPT ActiveX object created which is used to inject the Malicous JS in registry*/

return oWSS.RegRead(regpath);

}

function tst()

{

writeInRegistry("malware", "rundll32.exe javascript:\"\\..\\mshtml,RunHTMLApplication \";alert('payload'); "); /*Payload is the JS payload which does the real malicious stuff and it got watchdog, for keeping an eye over the registry entry which makes the infection persistent*/

alert(readFromRegistry("malware"));

}

</script></head>

<body>

Click here to run test: <input type="button" value="Run" onclick="tst()"

</body>

</html>

/***************************POC end*****************************************/

Figure 5: Proof of concept.

For our purposes, we picked the case of Poweliks, specifically because of how it extracts the JS from the Run registry entry. It is injected into the Run registry entry to make the infection persistent. Once the user restarts the computer, it reinjects itself, as in-memory infection will disappear once the computer is restarted.

For our POC, we used the Alert API, although malicious actors may choose differently. As in previous cases of fileless infection, we found that it features a watchdog module, which keeps an eye over the registry entry. It also recreates the registry entry if the user deletes it.

For simplicity, we have only shown how to execute the code. The same thing can be achieved using PowerShell or CSCRIPT.

This attack may affect all Windows versions from Windows 95 through to Windows 10. All versions have IE preinstalled, which, as previously discussed, comes with WSCRIPT, which is the only required component to perform this attack.

Other variants of similar attacks can be made using the following trusted applications:

Symantec recommends users adhere to the following best practices to prevent one-click fileless infection:

Anti-virus products have the following approaches to address fileless infections:

[1] Trojan.Poweliks. https://www.symantec.com/security_response/writeup.jsp?docid=2014-080408-5614-99.

[2] Trojan.Bedep. https://www.symantec.com/security_response/writeup.jsp?docid=2015-020903-0718-99.

[3] Trojan.Kotver. https://www.symantec.com/security_response/writeup.jsp?docid=2015-082817-0932-99.

[4] Camba, A. Unplugging Plugx Capabilities. Trend Micro Malware Blog. http://blog.trendmicro.com/trendlabs-security-intelligence/unplugging-plugx-capabilities.

[5] O'Murchu, L.; Gutierrez, F. The evolution of the fileless click-fraud malware Poweliks. Symantec Connect Blog. http://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/enterprise/media/security_response/whitepapers/evolution-of-poweliks.pdf.

[6] Microsoft Windows Remote Privilege Escalation Vulnerability (CVE-2015-0016). https://www.symantec.com/security_response/vulnerability.jsp?bid=71965.

[7] Kafeine. Angler EK: now capable of "fileless" infection. Malware Don't Need Coffee Blog. http://malware.dontneedcoffee.com/2014/08/angler-ek-now-capable-of-fileless.html.

[8] Anand, H. One-click fraudsters extend reach by learning Chinese. Symantec Connect Blog. http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/one-click-fraudsters-extend-reach-learning-chinese.

[9] Extreme Makeover: Wrap Your Scripts Up in a GUI Interface. Microsoft Technet. https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee692768.aspx.

[10] Recreated from the Microsoft TechNet (2013) gallery – IE Architecture. https://gallery.technet.microsoft.com/IE-Architecture-3bc7c3fd/file/78635/1/IE%20Architecture.png.

[11] HTML Applications SDK. https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms536473(vs.85).aspx.

[12] Hamada, J. The rise of Japanese zero-click fraud. Symantec Connect Blog. http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/rise-japanese-zero-click-fraud.

[13] It's a Wrap! Windows PowerShell 1.0 Released! Windows PowerShell Blog. https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/powershell/2006/11/14/its-a-wrap-windows-powershell-1-0-released.

[14] Using the command-based script host (CScript.exe). Microsoft Technet. https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb490887.aspx.

[15] WScript Object. Microsoft Developer Network. https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/at5ydy31(v=vs.84).aspx.