Check Point Software Technologies, Israel

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

In this work, we survey selected recent case studies of unfortunate cryptographic implementations in malware. When considered together, these examples illustrate a picture of design anti-patterns that is either worrying or encouraging, depending on one's point of view. Malware authors compose primitives based on gut feeling and superstition; jump with eagerness at opportunities to poorly reinvent the wheel; jump with equal eagerness at opportunities to use ready-made code that perfectly solves the wrong problem; and, ever‑pragmatic, take care to misinform their audience about how their software works, to dissuade anyone from taking too close a look.

We draw conclusions from these case studies that might be of use to those of us on the wrong side of the malware barrel – victims and analysts.

Cryptography has become part and parcel of malware. It is used to subject victims to extortion, perform covert communications and achieve stealth. But just as it is essential, cryptography is easy to misimplement. Even the most experienced and astute of developers are wont to be tripped up by the pitfalls of cryptography.

Most malware authors operate in a unique environment and are subject to unique incentives. They are as cynical about code quality as the most cynical developing houses: they are on a tight schedule, they have no customers to answer to, and they only care about quality design or implementation insofar as either of these things affects their immediate bottom line. Their creations survive by being stealthy, unique and simple; therefore, they would rather not borrow an existing solution to a large problem if they can help it.

This cocktail of constraints pushes malware authors into committing a class of errors that one would be hard pressed to find in legitimate software of any repute. These are not padding oracle vulnerabilities or goto-fails; these are basic misunderstandings of how to use cryptographic tools properly, which at best broadcast 'I have no idea what I am doing', and at worst cripple the malware catastrophically such that it does not actually do what it set out to do.

It is difficult to give this class of errors a name or a rigid definition. We have found that it is useful to look at them through the lens of design anti-patterns – specifically those that stem from the incentives to which most malware authors bow: a fuzzy understanding of the details, a great rush, and the temptation (sometimes necessity) to Do It Yourself.

The Jargon File [1] gives the following definition of 'voodoo programming':

'The use, by guess or cookbook, of an obscure or hairy system, feature, or algorithm that one does not truly understand. The implication is that the technique may not work, and if it doesn't, one will never know why.'

Voodoo programming is something beyond a mere dodgy implementation choice. It is an implementation choice that betrays a deep confusion about the functionality being invoked – what it is, what it does, and why it might fail. We describe two examples of malware we have encountered that, we believe, contain cryptographic code that falls under this category.

Zeus is a banking trojan that originated in Russia in 2007. It is estimated to have infected millions of machines and caused tens of millions of dollars in damages in the US alone [2]. In 2011, the source code of Zeus was leaked [3], which enabled a more thorough look through Zeus' internal functionality.

One of the major aspects of Zeus is its dependency on communication with a working C&C server. Much of the malware's functionality is configurable dynamically through this server, and Zeus periodically contacts it for further orders. The authors chose to encrypt all such control traffic with RC4, a popular stream cipher.

The security of RC4 is the subject of some debate, which we will not cover here. The bottom line is that, for the purposes required by the authors here, RC4 definitely ought to be secure enough, barring some egregious design error. However, the authors of Zeus did not share this feeling, which is why they introduced their own tweak: after the traffic is encrypted using RC4, every byte is modified by XORing it with the next byte to produce the final ciphertext [4].

It is not difficult to show that this tweaked variant of RC4 is exactly as secure as plain, vanilla RC4. The following Python script converts tweaked RC4 ciphertext to equivalent vanilla RC4 ciphertext:

chrxor = lambda c1, c2: chr(ord(c1)^ord(c2))

def untweakRC4(buf):

bytes = []

while(buf):

bytes = [buf[-1]] + bytes

buf = buf[:-1]

try: bytes[0] = chrxor(bytes[0],bytes[1])

except IndexError: pass #first byte

return "".join(bytes)

The authors either did not realize this, or did realize this, and were aiming for security by obscurity. Security by obscurity is not a recommended approach, least of all here, where there is plenty of encrypted traffic to analyse and plenty of Zeus samples floating around that can be reverse engineered.

The Linux.Encoder ransomware's initial claim to infamy lay in using rand() with the current timestamp as a random seed. This turned out to be insecure; the timestamp was invariably close to the victim file's 'last modified' timestamp, which enabled an efficient attack against Linux.Encoder encryption, as pointed out by Caragea [5].

Figure 1: Twitter reacts to the first version of Linux.Encoder.

Linux.Encoder's authors were subsequently met with a hail of ridicule on Twitter, and decided to go back to the drawing board. One of the modifications they eventually made to their malware involved hashing the timestamp eight times and using the result as an AES key [6].

Using a hash function eight consecutive times on an input shows a deep misunderstanding of what hash functions are. An ideal hash function is deterministic, easy to compute and difficult to invert. An ideal hash function, composed with itself, does not yield a better hash function, but rather an odd creation that has weaker security properties and is marginally less efficient to compute. The details will vary depending on the exact function used, but in all probability, they will not be good news.

It is true that hash functions used in the real world are not ideal mathematical abstractions, but their faults and vulnerabilities have not been shown to improve when composed with themselves, and it is not clear where the magic number eight came from.

Were the authors truly worried that their chosen hash function was not secure enough? We will probably never know; in the actual implementation, they neglected to choose a hash function at all. As a result, all eight calls to the hashing logic did not, in fact, do anything.

The late physicist Richard Feynman is known for many things, one of which is the popularization of the term 'cargo cult science' [7] – activity that superficially emulates science without emulating the core principles that make science work. From this neologism, others have derived 'cargo cult programming' – programming that emulates solutions to problems without understanding why, or how, these solutions work. This modus operandi is also, and more commonly, known as 'copying and pasting from Stack Overflow'.

Emulating a solution that is known to work is a viable strategy. It might, however, turn out to be the solution to the wrong problem. Without an understanding of what the solution does, one cannot really make the distinction, and might end up using code that performs almost what one had in mind, but not quite. The consequences can be dire, as we will see in the example below.

The recent flood of ransomware was preceded by a slow drip of copycats that goes back years, to the first pioneers who braved the unknown and copied what CryptoLocker did. One of the 'early adopters' to have been a part of this trend was CryptoDefense, a malware effort inspired by CryptoLocker, which surfaced around February 2014 [8].

On the face of it, CryptoDefense did everything by the book: RSA-2048 encryption, payment via Bitcoin, communication with C&C servers via Tor – where it matters, the authors put in the effort. One front on which they did not put in the effort, however, was re-implementing RSA. Instead, they reasonably opted to use a low-level cryptographic API offered by Windows OS.

To be more specific, they set out to acquire Windows' cryptographic services by calling the CryptAcquireContext API function. A typical developer would just use one of the many wrapper functions available for this API function, but malware authors are not typical developers, and one imagines they soon found themselves reading the MSDN documentation for CryptAcquireContext. The documentation [9] is typically exhausting, but thankfully at the end of it lies the holy grail – a fully formed call to CryptAcquireContext that just works, and can be copied. It goes as follows:

CryptAcquireContext(

&hCryptProv, // handle to the CSP

UserName, // container name

NULL, // use the default provider

PROV_RSA_FULL, // provider type

0); // flag values

And now all is right with the world, and the malware can invoke RSA to its heart's content. This code, or at least something suspiciously like it, appears in CryptoDefense verbatim. There is only one problem, though – which was noted first by researchers at Emsisoft [10], and which makes itself apparent to any soul brave enough to actually read through all of the documentation. It concerns a certain option that can be set in the flags variable:

| CRYPT_VERIFYCONTEXT | For file-based CSPs, when this flag is set, the pszContainer parameter must be set to null. The application has no access to the persisted private keys of public/private key pairs. When this flag is set, temporary public/private key pairs can be created, but they are not persisted. |

One might conclude that, if this option is not set, the application has access to the persisted private keys of public/private key pairs, which are persisted. Or, in other words, the private key is kept in the local key-store. A justifiable choice for some applications, but clearly not something the authors of CryptoDefense would have knowingly endorsed; their extortion pivot – the private key – was kept safely in the victim system, ready to be found by anyone who knew where to look. By taking advantage of this little misstep, Emsisoft researchers were able to reach out to victims and help them decrypt their files for free.

The adage goes, 'if you find yourself typing the letters A E S, then you are doing it wrong'. But malware operates under a set of constraints very unlike those relevant to most other software. If Joe Developer finds an open source project that solves a problem for him, he can happily lean on the project and save himself needless work; in contrast, if James Malware-Author finds himself in a similar situation, the way forward for him is not so simple. Compiling software with statically linked third-party code is a minor yet real hassle, compared to the cowboy programming typical of malware development. The extra code will bloat the executable size, and under certain circumstances, may well act as a giant neon sign announcing the malware's intent to the world.

Given the above, malware authors tend to improvise. If a solution to a problem cannot be copied and pasted from anywhere, but can be hacked together in 100 lines of code, a malware author will choose simply to hack together the 100 lines of code rather than comb the web for an existing solution and link against it.

When one sets out to reinvent the wheel, one takes upon oneself the risk of reinventing the wheel poorly. We list three examples of malware projects that ran head-first into that risk.

Petya, a member of the recent tidal wave of ransomware, made headlines due to its ability to encrypt the internal data structures of the victim's hard drive (such as the Master Boot Record and the Master File Tables). These abilities were pioneered by Petya; no other ransomware before it boasted this feature. Generally speaking, the Petya authors were tired of the same old ransomware routines and wanted to do something fresh and exciting, which is why – faced with the choice of encryption algorithm – they went with the lesser-known stream cipher, Salsa20 [11].

Salsa20 is thought to be more resistant against scary NSA-level attacks than its cousin stream cipher RC4, but that's really neither here nor there; the prototypical victim of ransomware is Aunt Alice and her precious vacation photos, and Alice does not work for the NSA (or at least her husband, Bob, believes as much).

Given that it is a lesser-known cipher, public resources detailing how to implement Salsa20 are less obviously abundant. The top result on programmer collaboration site Stack Overflow regarding Salsa20 involves a wide‑eyed newcomer asking how to implement that algorithm in C++, and a horrified regular contributor responding:

'If you are going to use Salsa20 in real code and you are asking questions like this, you probably want to use the NaCl library with nice friendly C++ wrappers.'

Having no patience for NaCl and with juicy ransomware dollars within their sight, the authors of Petya bravely rushed in where angels fear to tread and went at it – reimplementing Salsa20 from scratch. It was a difficult mission, the odds were against them, there were points at which all must have seemed lost. Naturally, given the above, they failed.

To understand how, we must first delve a little into Salsa20 – specifically its keystream. It is structured as follows:

On the face of it, this should be completely straightforward to implement. Yet, given the example set by Petya, it begins to emerge that if you believe anything in cryptography is completely straightforward to implement, either you don't understand cryptography, or it doesn't understand you. The Petya implementation of this apparently straightforward logic had no fewer than three distinct major flaws that made possible an attack on the resulting cipher.

The first flaw was the use of a 32-bit integer type for the 64-bit stream position key-stream value, which forces the high part of the stream position buffer to have the predictable value of 0.

The second flaw was in the implementation of the ROTL (rotate left) function:

static unit32_t rotl(uint32_t value, int shift) {

return (value << shift) | (value >> (32 - shift));

}

This re-implementation is nearly identical to the original, except for one difference – for an unknown reason, the authors chose to use 16-bit parameters instead of the original 32-bit.

The third flaw is located in the Salsa20 core hashing function responsible for producing the key stream. The original implementation receives a 512-bit input key buffer which is split into two internal 256-bit buffers:

static void s20_hash(uint8_t seq[64]) {

int i;

uint32_t x[16]; // <<< 32-bit vectors

unit32_t z[16]; // <<< 32-bit vectors

for (i=0; i<16; ++i)

x[i] = z[i] = s20_littleendian(seq + (4 * i));

for (i=0; i<10; ++i)

s20_doubleround(z)

for (i=0; i<16; ++i) {

z[i] += x[i];

s20_rev_littleendian(seq + (4 * i), z[i]);

}

}

Petya's implementation uses the same code but the internal buffers are – yes, you guessed it – wrongly downsized to 16-bit values:

static void s20_hash(uint8_t seq[64]) {

int i;

uint16_t x[16]; // <<< 32-bit vectors

unit16_t z[16]; // <<< 32-bit vectors

for (i=0; i<16; ++i)

x[i] = z[i] = s20_littleendian(seq + (4 * i));

for (i=0; i<10; ++i)

s20_doubleround(z)

for (i=0; i<16; ++i) {

z[i] += x[i];

s20_rev_littleendian(seq + (4 * i), z[i]);

}

}

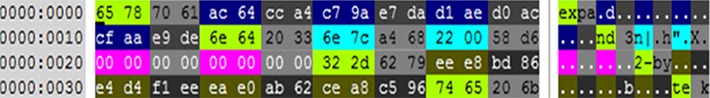

Thanks to these three flaws, Petya generates a 512-bit key containing 256 bits of constant and predictable values.

When your implementation of a cipher cuts its effective key size by half, and the required time for a break by 256 orders of magnitude, it's time to go and sit in the corner and think about what you've done.

Figure 2: Illustration of reduced-entropy key. Constant, predictable values of the key are coloured grey.

From this document one might get the impression that ransomware instances are the sole perpetrators of crypto failures in malware. Lest the reader leave with this false impression, we turn our attention to one of the most widely distributed exploit kits of recent times: Nuclear.

Nuclear has been around since as early as 2009, and has constantly evolved to keep up with developments in the exciting field of exploit kits [12]. Following in the footsteps of Angler and others, it eventually began obfuscating its exploit delivery by using Diffie-Hellman key exchange to encrypt information passed to exploits during execution [13].

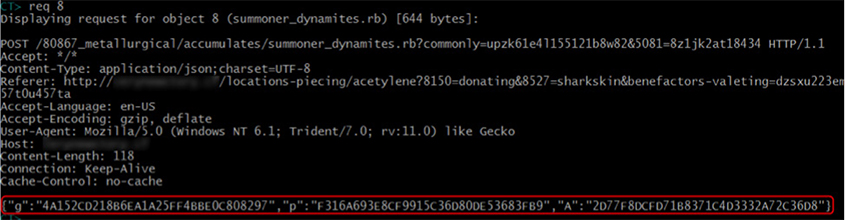

The variables needed for the Diffie-Hellman key exchange are sent by the exploit code to the server as a JSON file containing strings of hexdigits, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: JSON in transit.

Figure 3: JSON in transit.

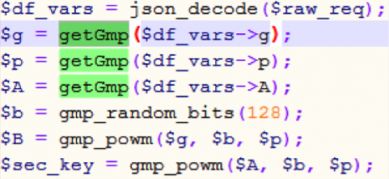

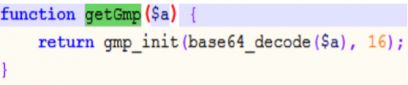

This JSON is parsed and each value is passed as a parameter to the getGmp() function:

Figure 4: Parameters being passed to getGmp function.

The getGmp() function handles the parameters using base64 decoding:

Figure 5: Base64 decoding takes place.

And everything is in order, except for one small technical caveat, which is that a string of hexdigits and base64 encoding are not the same thing.

getGmp() sees the stream of hexdigits, attempts to decode it as a base64 string, fails, shrugs, and returns False. The Nuclear server is then tasked with using this value as the infected client's public key. For a fleeting moment it stops and thinks, 'huh, false? How is that a key?'. The moment passes quickly. False, the server recalls, is just another name for the integer. Having realized this, the server then happily proceeds to follow the DH scheme as scheduled, and the same goes for the client. Thus, they successfully agree on a secret shared key:

Ab = 0b = 0 = 0a = gba =Ba

All future communication between the client and the server is encrypted using the secret key, 0.

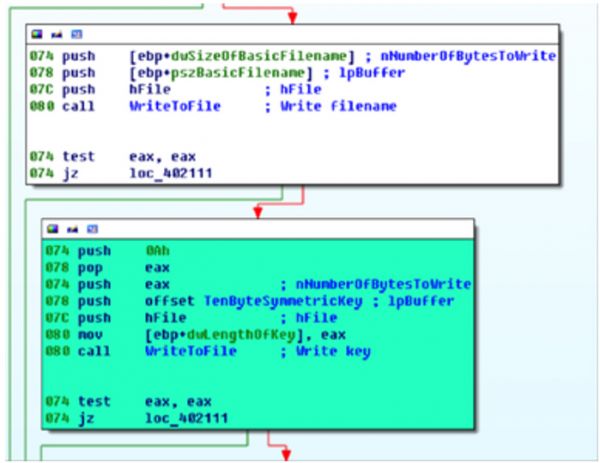

Like CryptoDefense, DirCrypt is an early contender that sought to ride the ransomware wave during 2014, when it was just getting started. Unlike CryptoDefense, DirCrypt does not check all the boxes for how to perform extortion 'properly'; rather, it makes its own bold artistic decisions, some of which are decent while others are less so.

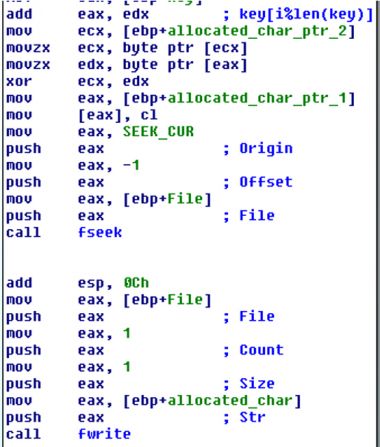

DirCrypt adopts a hybrid approach to encrypting victim files. The first 1,024 bytes are encrypted using RSA, and the rest are encrypted using the ever-popular RC4, which is a relative breeze to implement and therefore often finds its way into malware.

Unfortunately for the authors of DirCrypt, a system does not become secure just because you're using RC4. That cipher is, as mentioned earlier, secure enough for the purposes of presenting a total stumbling block to the typical malware analyst with only traffic to look at, but this only applies if the cipher is operated correctly. In the case of DirCrypt, the encryption machinery is invoked from scratch, using the same key, when encrypting each file [14]. This is a classical key-reuse vulnerability, and it exposes the encrypted files to trivial known-plaintext attacks, and even some known-ciphertext attacks (in particular see [15]).

Figure 6: DirCrypt stores the RC4 key in the victim file.

What makes the story of DirCrypt truly extraordinary, however, is not the key-reuse. That is an understandable mistake; to avoid it, one must have some elementary knowledge of how stream ciphers work and how they can fail, and sometimes you just don't know what you don't know. The truly astounding bit with DirCrypt is the design choice for where to store the RC4 key. The authors opted to keep the key appended to the encrypted file, where it is directly accessible to the victim. It thus became trivially possible to recover bytes 1024 and on for every encrypted file. For some files, with long enough and predictable enough headers, it became possible to recover the entire file this way.

In the game of malware authorship it is often the case that the winning move is to bluff. A malware author can work tirelessly to fortify their creation using the most impeccable cryptographic design and implementation; or, for a fraction of the effort, they can intimidate victims into believing that they have done so.

We present two examples of malware outright lying to victims, handing out baseless threats and promises in lieu of solid code to actually back up those threats and promises.

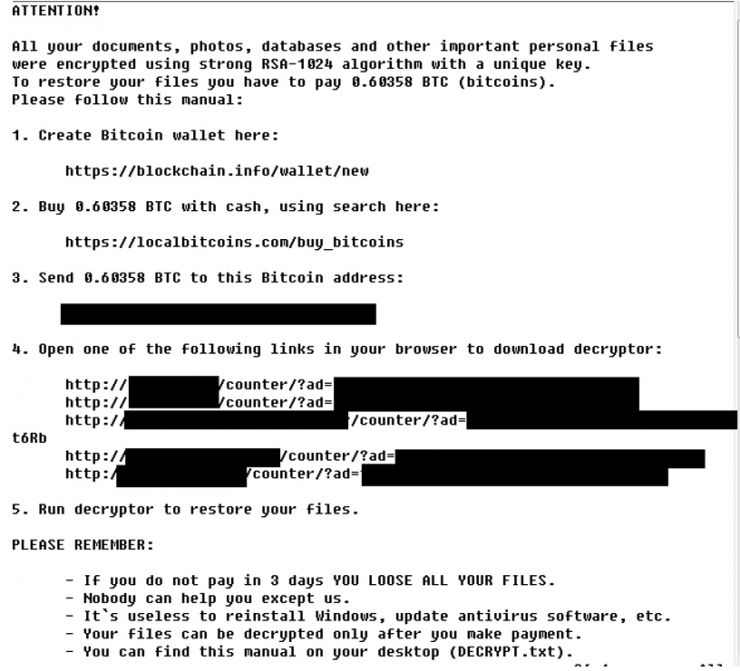

Nemucod is a JavaScript trojan, spread mainly through spam email. Originally a mere dropper, in early 2016 it decided to jump onto the now-speeding ransomware bandwagon. Users unfortunate enough to run the new and improved Nemucod soon faced a triumphant announcement that their files had been encrypted with RSA-1024 encryption and that they had no choice but to pay up.

Figure 7: Nemucod ransom note.

However, this triumphant announcement is, in fact, not entirely true. First of all, it is displayed after the necessary components for encryption have been downloaded from the campaign's C&C server, but before even a single file has been encrypted. If a victim's AV engine is vigilant enough, or if the downloaded encryption machinery meets with some other unfortunate accident, the encryption routine proceeds to fail hilariously: all 'rename file' calls that follow go through successfully, but all the 'encrypt' calls fail. The result is confused victims who have been quoted as saying, 'all this ransomware does is change your file extensions'.

Figure 8: Nemucod encryption logic. Not pictured: RSA-1024.

Of course, most of the time, the encryption will go through – but not the RSA-1024 encryption promised by the menacing ransom note. Rather, Nemucod encrypts files using a simple rotating XOR cipher. This is basically one step of sophistication up from XORing every byte with 0x55. As far as ransomware sophistication goes, Nemucod sets the gold standard for minimal effort. It trusts that this minimal effort should be enough, and that would-be adversaries will become light-headed and weak at the knees the moment they hear the phrase 'RSA-1024'.

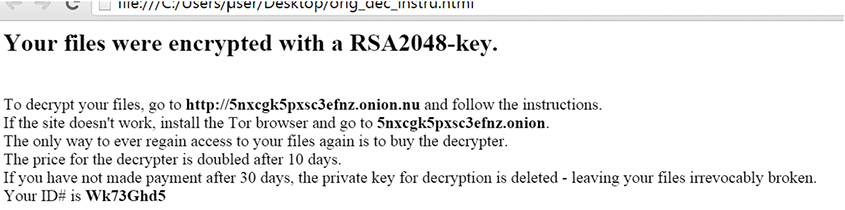

Poshcoder is yet another member of the first wave of CryptoLocker-act-alikes that hit the malware scene during 2014. It would be another faceless name in the crowd of ransomware but for several unusual features – first among which is the fact that it is written in Windows PowerShell.

Figure 9: Poshcoder ransom note.

Poshcoder, like Nemucod, makes empty threats of strong asymmetric encryption [16]. In fact, its fictional strong encryption is notably more heavy-duty than Nemucod's, as its various iterations claim to use RSA-2048 and even RSA-4096. The actual encryption being delivered is symmetric: victim files are encrypted using AES, not RSA. This is significant in itself, as symmetric ciphers are open to a number of attacks to which asymmetric ciphers are typically immune (all of which broadly fall under the headline, 'you had the decryption key at one point, all that's left is to find a surviving record of it'). Further probing into Poshcoder's encryption mechanism reveals the following:

$PASSWORD = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String(R2hjalJc[..]))

$SALT = [Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes("SqfmPRgx[..])

[..]

$RijndaelManaged_Var.Key = (new-Object Security.Cryptography.Rfc2898DriveBytes $PASSWORD, $SALT, 5).GetBytes(32)

[..]

$RijndalManaged_Var.Padding="Zeroes"

$RijndaelManaged_Var.Mode="CBC"

Rather than the RSA-4096 implementation it promises, Poshcoder actually encrypts victim files with AES using a fixed key. Eventually, the authors seem to have been alerted to the fact that this is not the best practice (if only by lost revenue). In response, they began routinely modifying the hard-coded key included with the PowerShell script. This may not be the best solution; when resorting to ransomware based on symmetric encryption, an author is betting the success of their scheme on the victim never recovering a record of their copy of the key. In this case, such a copy might well be available to download directly from the campaign's C&C server.

As we mentioned, malware not only makes empty cryptographic threats, but also empty cryptographic promises. Poshcoder, like the rest of its breed, posits a deal to its victim: pay up, and you can have your files back by the end of the hour. Unfortunately, Poshcoder's implementation of that functionality is not quite on the mark, either. A look into the encryption mechanism yields the following:

if($binReader.BaseStream.Length -lt 42871) {

$binReader_flen = $binReader.BaseStream.Length

} else {

$binReader_flen = 42871

}

[..]

$binWriter.Write($memStream_Array,0,$memStream_Array.Length)

[..]

Where binWriter writes to the victim file and memStream holds the AES-encryption of the first binReader_flen bytes.

First of all, we have here a short callback to the 'voodoo programming' header, above. As the author of the Malware Clipboard blog put it:

'I would almost pay the ransom value just to know why the author chose this arbitrary seeming value of 42,871 bytes.'

The more pressing issue here, though, is that this encryption logic irreversibly breaks any files longer than that. When such a file is given as input to this code, its first 42,871 bytes are encrypted; due to the zero padding, the length of the resulting ciphertext is not actually 42,871 bytes, but the closest larger multiple of 128 (AES block length) – which is 42,880. These 42,880 bytes overwrite the first 42,880 bytes of the victim file, and as a result, bytes 42871–42879 of the original file are lost forever.

For the missing nine letters in your interminable teenage diary, this error is a mere nuisance. For the missing nine bytes in the middle of the ZIP archive containing a backup of your financial records for the last three years, it would probably be more of an issue. The CRC32 checksum has failed; the archive is corrupted; have a nice day.

Many malware authors know that cryptographic tools are useful, and will achieve things that there are no other ways to achieve. All the same, evidence heavily suggests that most malware authors view those tools as wondrous black boxes of black magic, and figure they should be content if they can get the encryption code to run at all.

As a result, the cryptographic facilities of malware can offer pleasant surprises – if you know where to look. A solid forensic investigation can sway the outcome of a nasty ransomware incident, allow access to traffic that malicious actors would have preferred to stay secret, and, generally, allow subversion of whatever original functionality the cryptography was invoked for in the first place.

One day, malware authors will collectively figure out how to use encryption properly – and when they do, it's going to be a completely different playing field. Until that day, opportunities will abound – and malware analysts and victims had better keep their eyes open and their ears perked for these opportunities, as long as they are still here.

[1] Raymond, E. The Jargon File. 2003. http://catb.org/jargon/html/V/voodoo-programming.html.

[2] Finkle, J. Hackers steal U.S. government, corporate data from PCs. Reuters, 2007. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-internet-attack-idUSN1638118020070717.

[3] Goodin, D. Source code leaked for pricey ZeuS crimeware kit. The Register, 2007.

http://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/05/10/zeus_crimeware_kit_leaked/.

[4] Andriesse, D.; Bos, H. An analysis of the zeus peer-to-peer protocol. Technical report, VU University Amsterdam, 2013.

[5] Caragea, R. Linux.Encoder.0 technical writeup: a story about light-weight cryptanalysis and blind reverse engineering. BitDefender, 2015. http://labs.bitdefender.com/wp-content/plugins/download-monitor/download.php?id=1251711000741210279.pdf.

[6] Caragea, R. Third Iteration of Linux Ransomware Still not Ready for Prime-Time. BitDefender, 2016.

https://labs.bitdefender.com/2016/01/third-iteration-of-linux-ransomware-still-not-ready-for-prime-time/.

[7] Feynman, R. P. Cargo cult science. The Art and Science of Analog Circuit Design, p. 55, 1998.

[8] CryptoDefense, the CryptoLocker Imitator, Makes Over 34,000 in One Month. Symantec, 2014.

http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/cryptodefense-cryptolocker-imitator-makes-over-34000-one-month.

[9] CryptAcquireContext Function. Microsoft Corporation. https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/aa379886(v=vs.85).aspx.

[10] Wosar, F. CryptoDefense: The Story of Insecure Ransomware Keys and Self-Serving Bloggers. Emsisoft, 2014. http://blog.emsisoft.com/2014/04/04/cryptodefense-the-story-of-insecure-ransomware-keys-and-self-serving-bloggers/.

[11] Trafimchuk, A. Decrypting the Petya Ransomware. Check Point Software Technologies, 2016 .

http://blog.checkpoint.com/2016/04/11/decrypting-the-petya-ransomware/.

[12] Neagu, A. All You Need to Know About Nuclear Exploit Kit. Heimdal Security, 2015.

https://heimdalsecurity.com/blog/nuclear-exploit-kit-flash-player/.

[13] Unraveling a Malware as a Service Infrastructure. Check Point Software Technologies, 2016.

http://blog.checkpoint.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Inside-Nuclear-1-2.pdf.

[14] Artenstein, N. How (and Why) We Defeated DirCrypt. Check Point Software Technologies, 2014.

https://www.checkpoint.com/download/public-files/TCC_WP_Hacking_The_Hacker.pdf.

[15] Mason, J.; Watkins, K.; Eisner, J.; Stubblefield, A. A natural language approach to automated cryptanalysis of two-time pads. Proceedings of the 13th ACM conference on computer and communications security, 2006, pp. 235–244.

[16] A. (@CyberClues). How to Fail at Ransomware. Malware Clipboard, 2015. http://blog.malwareclipboard.com/2015/09/how-to-fail-at-ransomware.html.