Check Point Software Technologies, Belarus

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

In the cyberworld, specialized virtual environments are used to automatically analyse malware behaviour and prevent it from spreading and damaging real users' personal data, important corporate assets, etc. These environments are called sandboxes. Most modern malware, even those that perpetrate relatively simple attacks, try to evade sandboxes by using different sandbox detection techniques. When a piece of malware detects a sandbox environment, it can adapt its behaviour and perform only non-malicious actions, thereby giving a false impression of its nature, and hiding what it actually does once it reaches a user's system. This can lead to significant security-related problems.

In this paper, we focus on the techniques used by malware to detect virtual environments, and provide detailed technical descriptions of what can be done to defeat them. To showcase our theory, we discuss Cuckoo Sandbox, the leading open‑source automatic malware analysis system that is widely used in the world of security. Cuckoo Sandbox is easy to deploy and uses a malware analysis system which connects many features, such as collecting behaviour information, capturing network traffic, processing reports and more. Nearly all the largest players in the market, such as VirusTotal and Malwr, as well as internal anti-malware-related projects, utilize the Cuckoo Sandbox product as a backend to perform automatic behavioural analysis.

Specific Cuckoo Sandbox bugs, which allow malware to detect sandboxed environments, are described in our paper, as well as possible solutions for these problems.

When a sandbox environment is detected, a piece of malware can easily hide its malicious intent by masquerading as a legitimate application, presenting false information to the analysis engine.

As many vendors and companies rely almost blindly on the results produced in virtual environments (especially ones that use Cuckoo Sandbox), the false information presented by the malware can be critical. While other research exists, our work covers many more different techniques used by malware to detect virtual environments, as well as ways to defeat them. This is especially important as the field is constantly evolving. We also pay special attention to the Cuckoo Sandbox bugs that can allow malware to detect the virtual environment. Knowing how to defeat these evasion techniques will help us to achieve a dramatically increased successful emulation rate in virtual environments and to deliver vital information to customers.

In this paper we present a number of evasion techniques that we have found during extensive analysis of recent malware. We also share a software utility that helps to assess virtual environments. Our solution provides clear detection technique names as well as proposed fixes for each one. The information and software will be made available as open source material on our GitHub repository [1].

Let's describe implementation flaws in the Cuckoo Sandbox [2] product. Each evasion technique is discussed in the context of both the CuckooMon module [3] and the latest Cuckoo Monitor module [4].

To track process behaviour, the CuckooMon/Cuckoo Monitor module hooks relevant functions. In this type of architecture, the hook is called before the original function. A hooked function may use some space on the stack in addition to that used by the original function. Therefore, the total space on the stack used by the hooked function may be larger than the space used only by the original function.

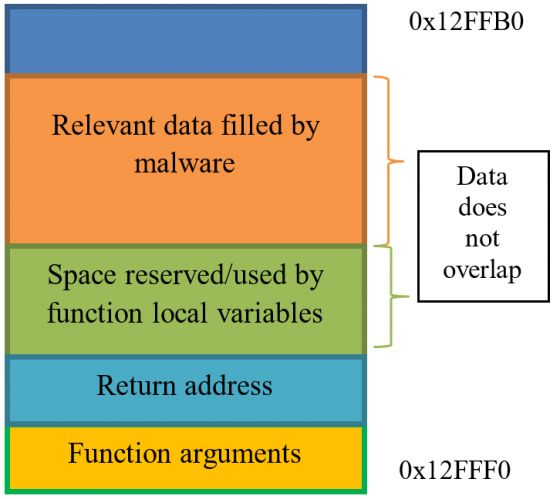

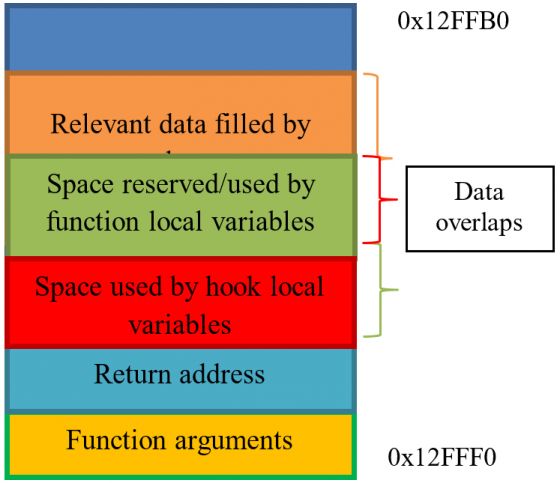

Problem: The malware has information about how much space the called function uses on the stack. It can therefore move the stack pointer towards lower addresses at an offset that is sufficient to store the function arguments, local variables and return address to reserve space for them. The malware fills the space below the stack pointer with some relevant data. It then moves the stack pointer to the original location and calls the library function. If the function is not hooked, the malware fills in the reserved space before the relevant data (see Figure 1). If the function is hooked, the malware overlaps relevant data, because the space that was reserved for the original function's local variables is smaller than the space occupied by the hook and the original function's local variables combined. The relevant data is therefore corrupted (see Figure 2). If it stores pointers to some functions that are used later during the execution process, the malware jumps to arbitrary code, occasionally crashing the application.

Figure 1: Stack on non-hooked function.

Figure 2: Stack on hooked function call.

Solution: To avoid this behaviour, the Cuckoo Monitor/CuckooMon module can use a two-stage hooking process. In the first stage, instead of the hook's code execution, it can move the stack pointer towards lower addresses of a specific size that will be enough for the malware's relevant data. Then, the function's arguments are copied under the new stack pointer. Only after these preparatory operations have been completed is the second stage hook (which performs the real hooking) called. Relevant data filled in by the malware resides on upper stack addresses, thus it is not affected in any way by the called function.

There are many problems with the sleep-skipping logic in the current implementation of Cuckoo Sandbox. It needs to retain sleeping logic in terms of queries for computer time, tick count, etc. At the same time it needs to skip non-relevant delays, as the emulation time is limited. The three main flaws that make it possible to evade the sandbox are described below.

Problem: According to the CuckooMon and Cuckoo Monitor architecture, all delays within the first N seconds are skipped completely. If the malware uses the sleep family function with an INFINITE parameter within the first N seconds, the program may crash. The source code is as follows:

push 0

push 0xFFFFFFFF

call Sleep

retn

Solution: At the beginning of the NtDelayExecution hook, check if the delay interval has an INFINITE value. If it is equal to INFINITE, call the original NtDelayExecution code.

Problem: According to the CuckooMon and Cuckoo Monitor architecture, all delays within the first N seconds are skipped completely. At the beginning of the execution process, the malware may perform time-consuming operations, after which the malware may sleep for a long period, causing long delays, and thus exceeding the limited emulation time of the sandbox.

Solution: Skip delays that are greater than a specific limit. For smaller delays, use approximation and accumulate delayed values. If the number of accumulated values from the same range has exceeded a specific boundary, further delays from that range are skipped.

Problem: According to the CuckooMon and Cuckoo Monitor architecture, all delays that are skipped are accumulated in a global variable. This variable is used while performing GetTickCount, GetSystemTime, etc. calls. The value of the variable is added to the real system time in order to avoid detection by skipped delays. This model is non-thread safe, and therefore the malware may spoof its output in the following way: it creates a thread that sleeps for a specific long period of time, so it will accumulate in the global variable. In another thread, the malware calls GetSystemTime, which is used, for example, in DGA [5]. As the current system time plus a long delay may exceed today's date, the generated domains will be non-relevant for today.

Solution: To avoid this behaviour, delay accumulation should be implemented on a per-thread basis. Delays in different threads will not affect each other's time-dependent behaviour.

To communicate with the machine, Cuckoo uses an agent server on the sandbox side. As the communication protocol is well known, the malware may use it to evade the virtual environment.

Problem: As an agent listens on some port (the default is 8000), the malware can enumerate all LISTENING ports. During enumeration, the malware may send specially crafted data and check the response. If the response matches a specific pattern, the malware can assume that the machine is running an agent.

Solution: While accepting incoming connections, the agent can perform a check of whether the incoming IP address belongs to one of the local machine interface addresses. If it belongs, the agent simply closes the connection.

To track process behaviour, CuckooMon and Cuckoo Monitor use function hooking. Both use trampolines [6] inside functions. Compared to CuckooMon, the new Cuckoo Monitor module has improved hooking, at least in terms of logic. The current version registers a notification function for the DLL first load by calling the LdrRegisterDllNotification function (in Windows Vista or later). Therefore, functions that should be traced and are not present in any modules at the Monitor startup are hooked after the first load of the module.

Problem: As hooks are implemented as trampolines, the CuckooMon/Cuckoo Monitor adds jumps at the beginning of functions. The malware can easily check if the first byte is equal to 0xE9 for some ntdll functions such as ZwClose, ZwDelayExecution, ZwGetContextThread, etc. At the same time, a check of whether the first byte is equal to 0xE9 can easily be performed for some kernel32 functions, CreateThread, DeleteFileW, etc. If the value of the first byte matches, the malware can assume that functions are hooked and it is running inside a sandboxed environment.

Solution: To avoid detection by hooks, a few possible solutions exist. One of these is to abandon user-mode hooks in the way in which they are currently implemented and to use a driver instead. A second solution is to use stack routing to implement function hooking.

CuckooMon and Cuckoo Monitor use a configuration file to perform initialization steps, as well as some system objects to communicate with the master. Evasion techniques based on such behaviour are described below.

Problem: Configuration files for the CuckooMon and Cuckoo Monitor are stored in the following paths (PID = GetCurrentProcessId):

The malware may check for the presence of such files in the filesystem. If the file is present, the malware can assume that it is running inside Cuckoo Sandbox.

Solution: If CuckooMon/Cuckoo Monitor is used in an internal project, the configuration file can be placed inside a shared object. The shared object name can be generated using the current date and process ID. Otherwise, the injector can use CreateRemoteThread/QueueUserAPC at the entry point of the manually mapped CuckooMon/Cuckoo Monitor module, previously writing configuration to allocated memory. The injector can pass the address of the written configuration as a parameter to this function.

Problem: The deprecated CuckooMon version uses the 'CuckooEvent%d' % PID event to notify the master that the module has successfully been injected into the tracking process. Malware can try to open the event by using the OpenEvent function with the specified event name. If the event is successfully opened, the malware can assume that it is running inside Cuckoo Sandbox.

Solution: If CuckooMon is used in an internal project, then the event name generation algorithm can use, for example, the current date and injected process ID. On the other hand, the new Cuckoo Monitor implementation uses a specific command sent over the pipe, which seems to be a very good solution as well.

If detection by configuration filename is a deficiency, then the malware may parse its content and look for the communication pipe name.

Problem: If the pipe name is known, the malware can send any commands to the pipe server as the protocol is well known. At the same time, the existence of such a pipe indicates that execution is taking place in a sandboxed environment.

Solution: As the pipe name can be obtained from the analyser configuration file and the Cuckoo Monitor configuration file, refer to the proposed solutions for these problems.

To start emulation of a specified file, the agent first copies all startup, fix and disguise scripts and DLL to a specific path in the system. The path contains SYSTEMDRIVE and a randomized folder whose name is between five and 10 characters in length.

Problem: The malware can enumerate SYSTEMDRIVE and check if the folders contain the following files or folders:

If these are present, the malware can assume that it is running inside a sandboxed environment.

Solution: To avoid detection by the presence of such files, the following solution can be implemented: use py2exe to compile all Python scripts with embedded CuckooMon/Cuckoo Monitor DLL content. That executable file is stored somewhere in the system under a random name.

Let's discuss some specific virtual environment detection techniques.

Problem: The malware tries to dump a raw firmware table, using an undocumented structure, to get information about the present firmware [7].

The SYSTEM_FIRMWARE_TABLE_INFORMATION (SFTI)object is initialized as follows:

sfti->Action = SystemFirmwareTable_Get;

sfti->ProviderSignature = 'FIRM';

sfti->TableID = 0xC0000;

sfti->TableBufferLength = Length;

The initialized SFTI object is used in the following way as an argument for the system information call to dump the raw firmware table:

NtQuerySystemInformation(

SystemFirmwareTableInformation,

sfti,

Length,

&Length);

If the operating system version is Windows XP or older, the malware uses CSRSS memory space to dump the raw firmware table:

NtReadVirtualMemory(

hCSRSS,

0xC0000,

sfti,

RegionSize,

&memIO);

The malware scans the received firmware table for the presence of the following strings:

Solution: In the case of Windows XP we use splicing of the NtReadVirtualMemory service. First, we need to parse the arguments. If the address of the read memory is equal to 0xC0000, then we modify the returned buffer, simply removing the specified strings from it.

In the case of Windows Vista and later versions, we hook the kernel mode service NtQuerySystemInformation. If the SystemInformationClass is equal to SystemFirmwareTableInformation, we start to parse the passed SFTI structure. If the SFTI member values are the same as described above, then we execute the original service and modify the returned SFTI structure, simply removing the specified strings from it.

Problem: This technique is quite similar to the previous one, except the malware tries to read the SMBIOS firmware table [7], and passes a different structure to the function calls:

sfti->Action = SystemFirmwareTable_Get;

sfti->ProviderSignature = 'RSMB';

sfti->TableID = 0x0;

sfti->TableBufferLength = Length;

If the operating system version is Windows XP or older, the malware uses CSRSS memory space to dump the raw SMBIOS firmware table:

NtReadVirtualMemory(

hCSRSS,

0xE0000,

sfti,

RegionSize,

&memIO);

Solution: The malware scans the received SMBIOS table for the presence of the same strings as described above. Possible solutions are also the same, except that the driver should check for a different address in the case of Windows XP (0xE0000), and a different ProviderSignature ('RSMB') as well as TableID (0x0) in the case of Windows Vista and later.

Problem: As almost all sandboxes disallow traffic outside the internal network, a problem may arise whereby the malware can access global web services in order to obtain some information that is hard to emulate in a virtual environment, for example:

Solution: To bypass such checks we need to adjust the routing inside our network to route such requests to our 'fake' services that replicate the real ones.

Problem: Some advanced malware overrides the system's default DNS servers, using public ones such as 8.8.8.8 or 8.8.4.4. So, even if a fake DNS server is set up in the sandbox, but not all the traffic is routed to it, the malware will not get a response and will stop its execution. Another possible problem is that the malware checks the number of records returned by the DNS server for the most popular websites, such as

google.com, yahoo.com, microsoft.com, etc. If your fake DNS server returns only one instead of multiple records, the malware will also stop its execution.

Solution: Fully emulate the real services and protocols. Return multiple DNS records if they should be present, as well as routing all DNS traffic to the server controlled by you.

Problem: Malware can obtain a valid date/time from the HTTP headers during access to a legitimate website. For example, the following are the HTTP headers while accessing google.com:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Cache-Control: private

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Location: http://www.google.by/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=Zn09V4uIDemH8Qfv3ZP4Dw

Content-Length: 258

Date: Thu, 19 May 2016 08:46:30 GMT

The malware could utilize the valid date/time in order to detect tampering with the date/time values in a virtual environment.

For example, let's look at the detection of sleep-skipping methods. Malware checks if there is a discrepancy between the sleep time and the time that has really passed. In the case of using sleep-skipping techniques, this will result in detection. The following is a section of pseudocode:

bool isSandboxed()

{

static const int kDelta = 5 * 1000;

static const int64_t k100NstoMSecs=10000;

bool sandboxDetected = false;

FILETIME ftLocalStart, ftLocalEnd;

FILETIME ftLocalResult;

FILETIME ftWebStart, ftWebEnd;

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime(&ftLocalStart);

getWebTime(ftWebStart);

const int64_t sleepMSec = 60 * 1000;

SleepEx(sleepMSec, FALSE);

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime(&ftLocalEnd);

getWebTime(ftWebEnd);

// PC's clock validation

ftLocalResult = ftLocalEnd – ftLocalStart;

ftWebResult = ftWebEnd – ftWebStart;

const int64_t localDiff =

abs(ftLocalResult) / k100NStoMSecs;

const int64_t webDiff =

abs(ftWebResult) / k100NStoMSecs;

if (abs(localDiff - webDiff) > kDelta)

sandboxDetected = true;

// second check for proper sleep delay

if (!sandboxDetected)

{

if (localDiff < sleepMSec)

sandboxDetected = true;

if (webDiff < sleepMSec)

sandboxDetected = true;

}

return sandboxDetected;

}

Solution: Fully emulate the real services and protocols. In such a case you should return the same date/time in the HTTP headers from the fake HTTP server as on the local machine.

Many malware families use various techniques to detect virtual environments. Some of these are trivial and the specific 'loopholes' they exploit are easily fixed. However, other techniques are more advanced and require extra effort. Depending on the detection technique, the malware may behave completely differently in a virtual environment from how it would in a real system.

Some of the described techniques are well known, but not yet fixed in a large number of virtual environments. Some techniques may have been used recently by specific malware (e.g. Locky, Qbot, Ramdo, Cridex, Matsnu, etc.), especially against Cuckoo Sandbox.

The worst problem is that some malware families don't just evade the emulation process, but also generate fake information (as seen, for example, in Locky and Ramdo).

There is still a lot of room for improvement in sandboxes, even if the emulation rate is sufficient. We hope that our research will serve as impetus for improvement in the Cuckoo Sandbox product and other virtual environments. At the same time, we expect that it will lead to better internal malware-related projects.

Evasion techniques and the detections they use represent an ever-evolving world. It's a classic cat-and-mouse game between malware developers and security researchers. Our future work will include tracking and fixing newly discovered evasion techniques to keep the emulation rate high enough for practical needs.

We would like to thank our colleague Aliaksandr Trafimchuk for helping us with our project.

[1] https://github.com/MalwareResearch/VB2016.

[2] https://github.com/cuckoosandbox.

[3] https://github.com/cuckoosandbox/cuckoomon.

[4] https://github.com/cuckoosandbox/monitor.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_generation_algorithm.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trampoline_(computing).

[7] https://github.com/hfiref0x/VMDE/blob/master/Output/vmde.pdf.