Virus Bulletin

Copyright © Virus Bulletin 2016

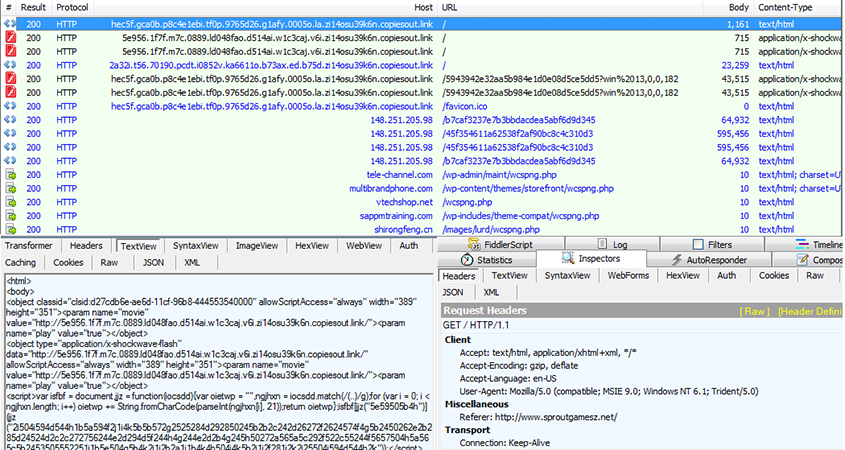

Rig, Angler, Nuclear, Magnitude. Few people outside security circles will have heard of them, yet they are behind what is possibly the worst large-scale malware plague ever: encryption ransomware. In particular, these are exploit kits which, when embedded into websites (often through compromised ads), check your browser for vulnerabilities and exploit them to push malicious software onto your computer.

Indeed, when, during our tests, we made requests to websites serving exploit kits, we found our test machines infected with ransomware such as Locky, Teslacrypt and Cerber, as well as other kinds of malware, including Bedep and Zbot variants.

Magnitude Exploit Kit traffic followed by Teslacrypt.

Many individuals and organizations have thus found themselves infected with malware in this way, and many have ended up paying hefty ransoms to attackers to get their files back.

Patching remains a great way to reduce the chances of being infected, but in decades of IT security we've learned that users often don't do what's best for them or their employer. As a result, many organizations rely on web security products that run on the gateway and filter web content for malicious responses.

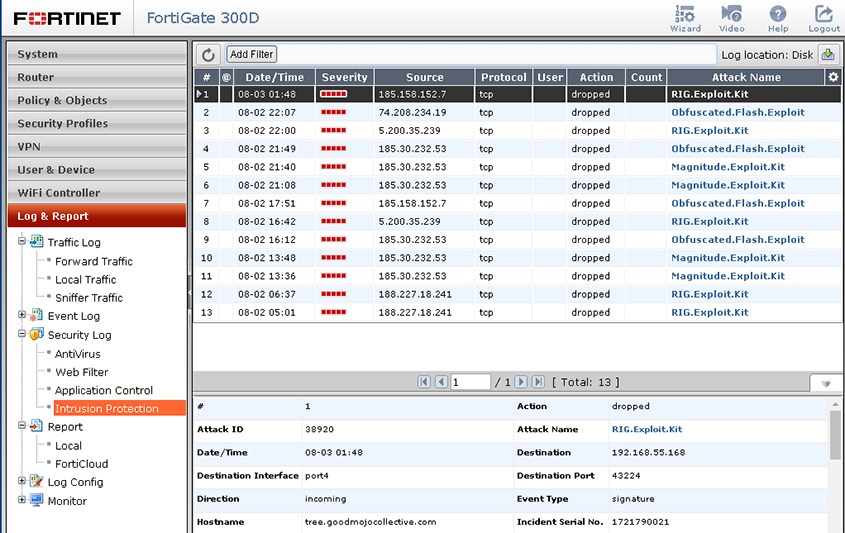

In Virus Bulletin's VBWeb tests we measure how effective products are at blocking malicious web traffic. In this report we focus on one particular product: Fortinet's FortiGate appliance.

During the test period, which ran from 1 to 11 April 2016, we used a number of public sources, combined with the results of our own research, to open URLs that we had reason to believe could serve a malicious response in one of our test browsers, selected at random.

When our systems deemed the response likely enough to fit one of various definitions of 'malicious', we made the same request in the same browser a number of times, each time with one of the participating products in front of it. The traffic to the filters was replayed from our cache.

Note that we did not need to know at this point whether the response was actually malicious, meaning that our test didn't depend on instances already known to the industry or community. During the review of the corpus days later, we analysed the responses and included cases in which the traffic was indeed malicious.

While we registered various types of malicious responses, including spam/scam sites and phishing pages, we decided to concentrate only on drive-by downloads, where the URL was an HTML page that forced the browser to download and/or install malware in the background. This is by far the biggest threat at the moment and makes unprotected web browsing more dangerous than ever.

In this test, we checked products against 439 cases, including 105 drive-by downloads (exploit kits) and 100 direct malware downloads that were all served in real time, while the malicious server was live.

We also checked the product against 234 URLs that we call 'potentially malicious'. These are URLs for which we have strong evidence that they would serve a malicious response in some cases, but they didn't when we requested it. There could be a number of reasons for this, from server‑side randomness to our test lab being detected by anti-analysis tools.

While one can have a very good web securityproduct that doesn't block any of these, we do believe that blocking them could serve as an indication of a product's ability to block threats proactively, without inspecting the traffic. For some customers this could matter, and for developers this is certainly valuable information, hence we decided to include it in this and future reports.

The test focused on unencrypted HTTP traffic. It did not look at very targeted attacks or vulnerabilities in the product themselves.

We used two virtual machines, selected at random, from which to make requests. On each machine, an available browser was also selected at random.

We found that, in practice, we were far more likely to receive a malicious response for the Windows 7 machine using either version of Internet Explorer, hence most of the cases that ended up in the test used this configuration.

This machine had the following software installed:

The following browsers were installed:

This machine had the following software installed:

The following browsers were installed:

Drive-by download rate: 87.6%

Malware block rate: 98.9%

Potentially malicious rate: 96.1%

FortiGate was the only participant in the last VBWeb report and easily achieved a VBWeb award, not least thanks to a near perfect blocking of direct downloads of malicious files. It did the same again in this test, blocking all but one of these files, thus protecting users and organizations well against supposedly helpful programs that turn out to be a real hindrance.

The product also blocked the vast majority of drive-by downloads, missing fewer than one in eight of the exploit kits it was served, and performed really well on blocking potentially malicious URLs too. All in all, a great performance and the appliance fully deserves its second VBWeb award.

FortiGate: excellent all-round protection.

FortiGate: excellent all-round protection.