Intel Security, UK

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

Anti-malware and other security products form the most visible part of any cyber defence, but the security industry often overlooks the fact that we also have several ways of exerting financial pressure on the bad guys. This pressure can be a proactive and potentially very effective tool in making our computer ecosystems safer.

Certain technologies are well suited to helping apply economic pressure on the players of computing ecosystems. By cleverly employing various trust metrics and technologies such as digital signing, watermarking, and public-key infrastructure in strategically selected places, we can encourage good behaviours and punish bad ones. For example, security products and services often employ blacklisting and whitelisting for software packages. Yet it is significantly more effective to apply this classification to the developers, software houses, distribution channels and players in the application monetization space (like Perion, Iron Source, etc.) and software distribution points (app markets and app stores).

We shall analyse and give examples of technologies (certificates, credentials, etc.) to de-incentivize bad behaviours in several ecosystems (Windows, Android, iOS) and slice them into subsystems that bear separate monetary tools (for example, membership fees and/or subscriptions):

We'll discuss and compare the costs of building defences based on financial deterrents versus the cost for the attackers to abuse them.

The security industry's fight against adversaries in cyber space shares some traits with a long-lasting military conflict. These include defences, attacks and breaches, casualties and collateral damage, technological advances on both sides, and crimes and punishments.

As security professionals, we are engaged in technological and intellectual competition with the attackers. Virus writers in the 1990s had underground electronic magazines (like the notorious 29A), in which they shared ideas and proofs of concept (including malicious code). That was a time when most malware was written by curious enthusiasts trying to prove themselves and by youngsters who could not get a date.

The 1990s may have set the tone for the anti-virus industry. In recent years the focus of our adversaries has drastically changed – it is now predominantly financial – but in AV security labs many researchers still feel that they are fighting a technological war. But are we really? And even if we are, should we be fighting a technological war?

As in any war, both sides have to balance their costs against benefits. 'Winning at all costs' is not how either side operates; the return on investment (ROI) is a major factor for both sides. Instead of focusing on perfecting our product technologies, we ought to work on embedding effective financial deterrents into cyber ecosystems. By employing economic measures (in conjunction with improvements in product technologies) we have a better chance of making the ecosystems cleaner and safer.

Some say that current deterioration of cyber security is associated with the Internet. However, technologies often create new possibilities for financial abuse. The introduction of coined money quickly led to its theft. Gangsters used cars to get away faster after robbing banks. Phone lines were tapped to steal and often sell secrets. There are many examples of abuse of new technologies. Computers, networks and the Internet are still relatively new, and their associated technologies are constantly evolving – which makes them particularly easy to attack. The following factors have a strong influence on the ROI of cybercriminals:

Table 1 shows the spectrum of technologies in the arsenal of AV products from the perspective of how they affect the costs for attackers. (We only look at the cost element because product technologies have minimal effect on the attackers' risks and rewards.)

| Technology | Cost for defenders (to create) | Cost for attackers (to bypass) |

| Hashing of programs | Low | Low |

| Fingerprinting | Medium | Medium |

| Behavioural fingerprinting | Medium | High |

| IP/URL/domain blocking | Low | Medium |

| Exploit blocking | High | High |

| Developer blocking | Low | Medium |

| Digital signature blocking | Low | High |

Table 1: AV technologies and how they affect costs for attackers.

We can see that blocking abused digital signatures appears to be the most effective approach for security products – our cost is minimal yet it is not easy for attackers to procure a new one. They have to purchase or steal. Neither of these actions is easy to automate.

Windows has had digital signing of software (also known as authenticode) for quite some time. Let's analyse how authenticode has been attacked over the years.

Security products and services often employ blacklisting and whitelisting for software packages. Yet it is significantly more effective to apply this classification to the developers and software houses.

OS drivers have had to be digitally signed since Windows Vista was released. That measure forced OS-level malware (rootkits and APTs like Stuxnet) to procure private certificates to allow their modules to be loaded during the OS startup. This is not an easy step and possibly required physical intrusions to steal the required files.

During an installation of any software, Windows will warn users if the software is not signed. So, over the years, users have learned to more readily trust signed installation packages.

Moreover, AV products also block or allow software signed with, correspondingly, previously abused or trusted certificates. They employ whitelists and blacklists and compute the reputation of everything 'grey' in between. The origin of software as determined from its authenticode signature is an important factor in this determination.

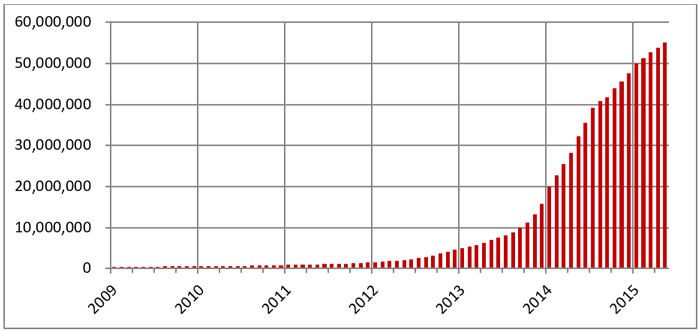

It is very desirable for malware – as well as for potentially unwanted programs (PUPs) – to masquerade as legitimate programs, but this requires access to private public-key infrastructure (PKI) certificates. Only when these are available can attackers sign and distribute their creations and impersonate a software source with a good reputation. Figure 1 shows a cumulative graph of malware and PUPs that are correctly digitally signed (authenticode). The growing trend indicates without a doubt that attackers find it beneficial to distribute their creations in a signed form.

Figure 1: The growth of digitally signed malware and PUPs (Source: Intel Security Labs).

Figure 1: The growth of digitally signed malware and PUPs (Source: Intel Security Labs).

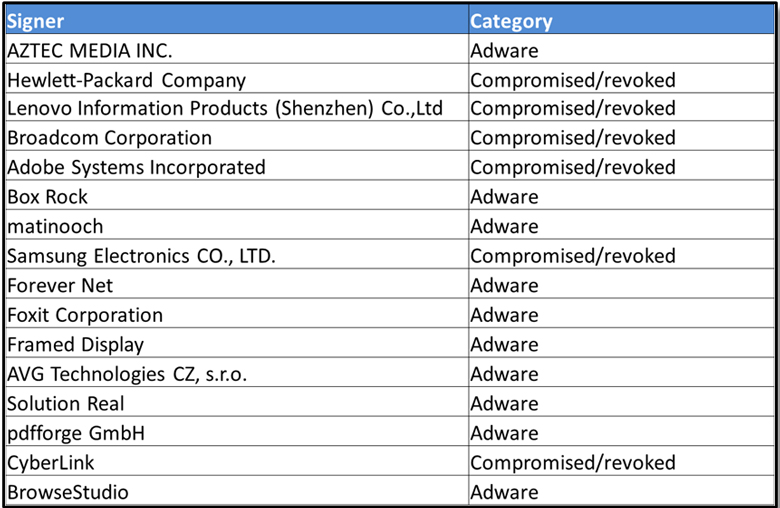

If we look at the 15 most commonly abused code-signing certificates in Figure 2, then the pattern becomes fairly clear. They consist of two large groups:

Figure 2: The 15 most common authenticode certificates in malware and PUPs (Source: Intel Security Labs).

Figure 2: The 15 most common authenticode certificates in malware and PUPs (Source: Intel Security Labs).

For malware authors, manually hunting in order to steal a private PKI certificate is, of course, very hard. An alternative is to purchase code-signing certificates, but that carries an upfront cost before malware distribution. The cheapest code-signing certificate costs around US$75 (or $140 for two years) from Comodo. And after being used to sign malware, the certificate will likely soon appear on a blacklist due to its association with malware. This cost, combined with the risk of loss, should be sufficient to discourage the majority of first-time malware writers.

However, PKI costs are clearly not enough to discourage software companies involved in PUP distribution (adware and ad-supported software bundles). These companies cannot be involved in stealing PKI certificates – such behaviour would automatically cross the line and place them squarely in the malicious category. So adware/PUP operators have no choice but to legitimately purchase code-signing PKI certificates.

To avoid the upfront PKI costs, malware authors make their creations look for certificate files on infected computers and steal them. Any program that looks for PKI certificate files and sends them out is malware – there is no situation in which legitimate software would need to do this. Data presented at the VB2014 Conference in Seattle clearly shows that the malware authors have a steady, and perhaps even growing, interest in stealing private authenticode certificates [1].

To summarize: there is no doubt that authenticode digital signing makes it costly to misbehave. By associating software with the source, the defenders make attackers either pay real money or jump through awkward hoops to steal certificates (and with no guarantee of success).

Let’s now have a look at alternative ecosystems and see how digital signing affects behaviours in mobile platforms iOS and Android.

To register as an iOS developer costs US$99 (or $299 for an enterprise licence, which gives more freedom in distributing apps). However, if the app store operator (Apple) finds that a developer has violated the rules (and distributing malware is certainly a violation), the licence will be cancelled. Anyone who violates the rules will have to pay again. This method is even more restrictive than authenticode signing in Windows because all apps are signed by Apple, which reserves the right to instantly exclude any misbehaving apps from the app store. So in iOS, attackers do not even have a short time window while the revocation list reaches the endpoints. It would be equivalent to immediate revocation of an authenticode certificate in Windows.

The Android ecosystem is slightly more lax. The developer registration for Google Play is US$25 (as of June 2015). The Google Play ecosystem is similar to that of iOS: any misbehaving developer loses their money. Android uses self-signed developer certificates, but Google Play (as well as any other third-party Android app market) can expel a developer for misbehaviour. Thus the app market operator (Google, for Google Play) exercises a measure of control that is similar to putting bad developers onto a blacklist.

However, if one does not want to pay, there is the option of distributing apps via numerous third-party app stores. Many of these are quite popular in non–English-speaking countries – China, Russia, Brazil, etc. – which make up a significant portion of the market. The default configuration in most Android phones is only to allow apps to be downloaded from Google Play, but any user can open a phone to third-party app stores to get a wider choice of local apps.

Both mobile ecosystems – iOS and Android – require digital signatures from developers, and both Apple and Google put misbehaving developers onto a blacklist, which costs them real money (albeit about four times more for iOS).

Both iOS and Android are derived from Linux, and their security posture is similar. However, in comparing these ecosystems we notice that the more restrictive and costly iOS is nearly malware-free, while the cheaper Google Play has a moderate number of malware and the unregulated third-party Android markets have a very serious malware problem:

| Mobile OS | Cost of misbehaviour | Scale of malware problem |

| iOS | US$99 | Negligible |

| Android (Google Play) | US$25 | Low |

| Android (third-party markets) | None | Serious |

Table 2: Cost of misbehaviour and scale of malware problem of different mobile OSes.

The scale of the malware problem in mobile OSes appears to be directly influenced by the cost of misbehaviour.

We can speculate that the significantly more expensive iOS developer licence creates an incentive for malware authors to apply their skills to the Android OS, in which they have a choice between free but limited malware distribution, or a paid but significantly wider scope.

Let’s have a look at other digital signing schemes – those that were designed to reduce the malware problem by introducing financial pressure on misbehaviours where none had previously existed.

The IEEE taggant system was created to reduce the problem of packed malware by positively identifying the software origin [2, 3]. The system is now offered as part of the IEEE Anti-Malware Support Service (AMSS [4]) by the IEEE Industry Connections Security Group (ICSG) [5].

Before the introduction of taggants, any malicious program could be repacked and redistributed at nearly zero cost by employing pirated and evaluation versions of packers. The taggant system attacks this via:

Taggants introduce a cost for packer abuse. Malware authors will face the situation in which they have to choose among three options:

These measures should improve the health of the packed software ecosystem by introducing incentives for wider adoption of taggants and by creating a cost for bad behaviours.

We know how malware authors reacted to a wider use of authenticode. They coded certificate-stealing routines and added them to their malware. We should expect the same for packers: malware will start stealing valid taggant certificates. That was one of the reasons why the IEEE taggant working group decided to keep the certificates of packer vendors at a centralized, secure portal; this measure minimizes the risk of compromise on that level.

To fully analyse all the costs in the taggant ecosystem we have to look at five types of players in the system: malware authors, AV companies, packer vendors, packer users (software companies that use packers to protect a game, for example), and users (who run packed software such as a game). A detailed paper by Singh and Lakhotia has a full game-theory review of the taggant ecosystem, which specifically analyses its economics [6]. The authors draw some interesting conclusions:

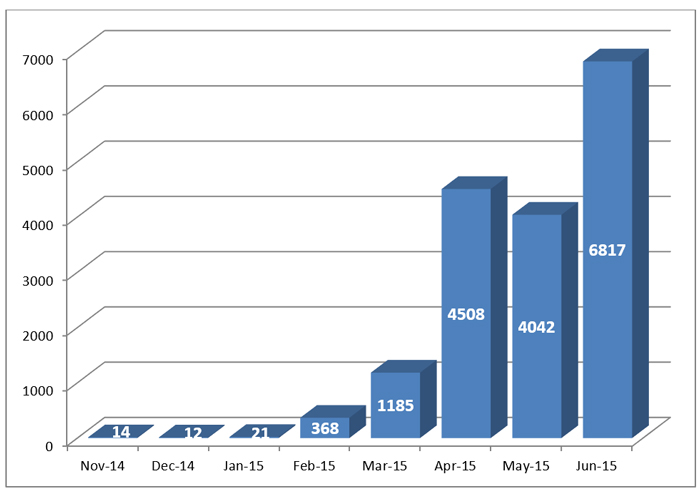

We are delighted to see that the number of packer vendors, as well as unique observed packed files, is steadily growing, as Figure 3 clearly demonstrates. It is, of course, still a drop in the ocean but the growth rate is very promising and a good indication of the taggant system attracting packer vendors.

Figure 3: The growth of unique packed files with taggants. (Source: Intel Security Labs.)

Figure 3: The growth of unique packed files with taggants. (Source: Intel Security Labs.)

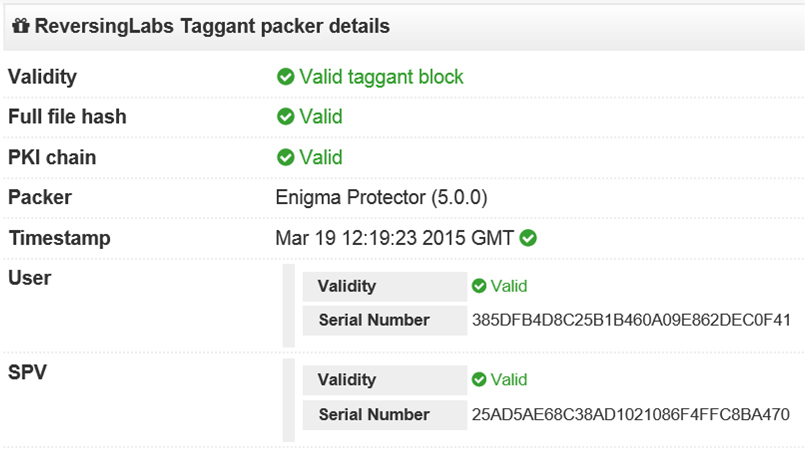

We are also pleased that VirusTotal (www.virustotal.com) has implemented support for the reporting of details included in the taggant; Figure 4 shows an example ('beta' output, not final). This free tool allows anyone to inspect the validity of the taggant, but it does not provide an automatic check against the global blacklist. Only IEEE AMSS subscribers get that.

Figure 4: An example of a VirusTotal report about a taggant based on the ReversingLabs tool.

Figure 4: An example of a VirusTotal report about a taggant based on the ReversingLabs tool.

This is a successful starting point for taggants in packed files. Now let's turn our attention to one other burning problem – software bundling.

For any new programmer, software distribution is a major problem. Even a great program can remain unknown, with nobody willing to pay for it. At the same time, developers cannot work for free. This is a catch-22 situation for new developers who want to enter the market. There are two solutions, specific to smartphones and to desktops:

Unfortunately, both types of ad-supported ecosystems are complex and they frequently intrude on users' privacy [8] or attempt to control users' searches and downloads by piggy-backing on free software [9]. These questionable behaviours are quite common, and AV companies have been trying to enforce some security rules. (Read a fascinating and horrifying case study [10].) Many ASDPs are also unhappy with this situation. There are no agreed rules – some AV vendors are stricter than others; and the OS, browser, and search engine vendors have a natural advantage over other ASDPs, which hurts their business. To summarize: the major players feel the need for defined rules and better control in this complex ecosystem. This need has resulted in the collaborative initiative called the Clean Software Alliance [11].

From the technology perspective, this area is difficult to regulate for the following reasons:

To ensure that we can identify and distinguish all these individual cases, we need technology for tracking the code contributions on three levels: program binary, installation file, and installation bundle. We also need to track the program distribution chain not only at its origin (developers can and should sign their programs) but so that all intermediaries, bundlers and distribution sites can add their 'stamp', as well.

Moreover, we need to track an app's installation history. When a program is found on a device with no information about how it was installed – with or without the user's consent – we are faced with a real quandary. In many cases this puzzle will not be possible to solve if there are no hints as to what steps led to the installation. That is why the installation history (properly logged with data that can be trusted) is so important.

The Clean Software Alliance needed a technology to support its effort, and the taggant system has emerged as a primary candidate. However, the taggant system required certain changes to accommodate these multiple new uses, so we at the IEEE ICSG added the following:

Thus far, the taggant Version 2 has passed more than 160 compatibility tests and will soon be released as open-source on GitHub, just like Version 1 [12]. Whether the Clean Software Alliance will employ the new taggant remains a question. At the very least, it is now a matter of negotiations and politics; the technology is ready.

Various forms of digital signing coupled with the blocking of misused certificates is very well suited to applying economic pressure on the abusers of computing ecosystems. By employing these methods we can encourage good behaviours and punish bad ones.

Making attackers spend real money before they can deploy malware is likely the best deterrent. Every time we find a way to apply more negative financial pressure on malware authors, we are likely to discourage many thousands of them.

As security industry practitioners, we must always think of ways to create new ecosystems and adjust current ones to make malware development and aggressive software costly, awkward, and risky. We can achieve this by applying PKI technologies while ensuring smooth operations for legitimate developers and users.

If you want to take part in such collaborative projects in the future, please feel free to contact the IEEE ICSG

([email protected]).

I am very grateful to all the participants in the IEEE taggant project and especially to Peter Ferrie, Mark Kennedy, Samir Mody and James Wendorf, who played major roles in bringing the taggant system to life. Thanks also to my Intel Security colleagues Patrick Knight and Craig Schmugar for providing data on adware and the level of authenticode abuse.

[1] Popescu, A.; Jescu, G. Can we Trust a Trustee? In-Depth Look into the Digitally Signed Malware. Proceedings of Virus Bulletin 2014 International Conference, Seattle, pp.183-188. https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2016/01/paper-can-we-trust-trustee-depth-look-digitally-signed-malware-industry/.

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Software_taggant.

[3] http://standards.ieee.org/develop/indconn/icsg/taggant.pdf.

[4] http://standards.ieee.org/develop/indconn/icsg/amss.html.

[5] http://standards.ieee.org/develop/indconn/icsg/.

[6] http://www.cacs.louisiana.edu/~arun/papers/2011-MALWARE-game-theoretic.pdf.

[7] https://blogs.mcafee.com/mcafee-labs/free-mobile-apps-compromises-user-safety.

[8] http://www.mcafee.com/uk/resources/reports/rp-mobile-security-consumer-trends.pdf.

[9] http://blog.brandverity.com/2738/software-bundlers-target-browser-brands-is-this-trademark-abuse.

[10] http://www.howtogeek.com/198622/heres-what-happens-when-you-install-the-top-10-download.com-apps/.

[11] http://uk.pcmag.com/opinion/37074/changing-the-way-we-fight-malware.