IBM Trusteer, Israel

Copyright © 2016 Virus Bulletin

Part of the work security researchers have to go through when they study new malware or wish to analyse suspicious executables is to extract the binary file and all the different satellite injections and strings decrypted during the malware's execution.

Usually, this initial process is done manually, and it can be lengthy or even end up incomprehensible, in case some actions the malware has taken are not traced back to it.

Enter VolatilityBot. This is a tool I have developed myself, leveraging the Volatility Framework. This new automation tool for researchers cuts all the guesswork and manual tasks out of the binary extraction phase. Not only does it automatically extract the executable (exe), but it also fetches all new processes created in memory, code injections, strings, IP addresses and so on.

Beyond the obvious value of having a complete extraction automated and produced in under a minute, VolatilityBot is highly effective against a wide variety of malware codes and their respective load techniques. It can take on complex malware including banking trojans such as ZeuS, Ramnit, and Dyre, just as easily as it extracts payloads from downloaders such as Upatre and Pony, or even from targeted malware like Havex.

Once VolatilityBot has finished the extraction, it can further automate repair or prepare the extracted elements for the next step in analysis – for example, by fixing the Portable Executable (PE), preparing for static analysis via tools like IDA, performing a YARA scan, etc.

The Volatility Framework at the core of this automation tool is an open-source framework for memory analysis and forensics; it analyses the runtime state of a system using the data found in volatile storage (RAM). You can find out more about Volatility at http://www.volatilityfoundation.org/.

VolatilityBot is an automatic modular framework that extracts malicious code from packed binaries, leveraging the functionality of the Volatility Framework. As such, VolatilityBot can dump all malicious injected code, loaded kernel modules and new processes created, from memory.

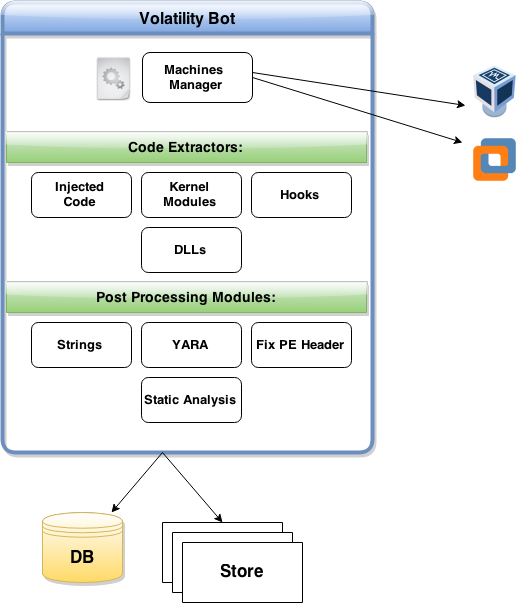

VolatilityBot is made up of four major components:

This is the core of the VolatilityBot tool. The manager executes the automatic extraction as well as the post‑processing modules. This module also controls the associated machines’ activity to streamline the workflow.

This is an abstract design of a research machine; it contains five functions: Revert, Start, Suspend, Clean-up and Get Memory Path.

Each machine has a very small python agent running, which listens and waits for a malware sample. When a sample is sent, it executes it by double-clicking. The agent is of minimal size in order not to affect the behaviour of the malware in the machine. The agent does not perform any API hooking and does not control the machine in any form besides executing the malware.

The machines are controlled and monitored by the manager component, which knows not to send more samples to a machine if it has fatal errors and will mark the machine as unavailable.

The code extractor component is a number of modules grouped together for the purpose of extracting all the different malicious code components from the memory. These are separate for code injections, new processes, etc. This component is modular, which allows researchers to write new code for other extractors they may need.

The existing modules for this component are as follows:

The post-processing modules kick in once the extraction is complete. They are tasked with automated actions like fixing the PE, or availing the resulting elements to static analysis, YARA scans, strings and IP address logging, etc.

These modules can help with:

Figure 1: VolatilityBot high level design.

Figure 1: VolatilityBot high level design.

The flow of events follows the previous section’s numbering, starting with the manager and ending with post-processing.

The manager (.py) module is executed first, alongside a folder containing binaries or a single file set as a parameter. The manager proceeds to build a queue of all the samples to process and adds them to a database. The manager module then locates an idle research machine/VM that can carry out the next step, and sends the file over to it.

Next, the agent on the research machine/VM executes the file and ‘sleeps’ for a predefined length of time that can be set by the researcher as per his or her preferences. The machine is then put in a suspended state.

In the third step, all configured code extractor modules are executed. Memory dumps are stored, and metadata is saved in a designated database.

Finally, once the extraction phase has completed, all the configured post-processing modules are executed.

The manager is multi-threaded and is configured to take advantage of all machines at the same time. Each sample processing on a machine has its own thread, which is terminated once the processing of the sample has finished. Processing of a sample refers to both the machine executing the sample and to all the code-extraction and post-processing modules after the machine is suspended.

Some of the core capabilities of this automation tool were designed to make it as scalable as possible and easy to work with over time:

In terms of additional modules that may be deemed necessary in the future, researchers working with VolatilityBot will find that its modular structure makes it very easy to write additional modules, whether code-extractor modules or post-processing ones.

Hundreds of samples have been tested in VolatilityBot. I used a research environment comprised of five Windows XP (x86) machines (VMware-powered). Each sample was executed for exactly a minute and a half.

A couple of malware subsets were created and run through VolatilityBot:

I took two subsets from the latest VirusShare archive and ran all of them through VolatilityBot. Table 1 shows some statistical information regarding the results.

| VirusShare Subset I | |

| Total samples | 1,750 |

| Samples with at least one successful dump | 1,658 |

| Injected code extractions | 256 |

| New processes dumped | 1,637 |

| Kernel modules dumped | 72 |

| Total storage used | 3.72 GB |

| VirusShare Subset II | |

| Total samples | 2,125 |

| Samples with at least one successful dump | 1,737 |

| Injected code extractions | 736 |

| New processes dumped | 1,726 |

| Kernel modules dumped | 47 |

| Total storage used | 4.7 GB |

Table 1: Statistical information regarding the results of running samples from VirusShare through VolatilityBot.

Note that not all of the samples referred to in Table 1 inject code or load a kernel driver. Some of them are just installers of potentially unwanted programs and some of them might be corrupted executables.

I noticed a high success rate in general, for all samples in the subset. Success is defined by the ability to extract injected code, a kernel module or dump of a process.

Another test was carried out that was more malware family and category-oriented. Table 2 shows the statistical information regarding these results.

| Malware families’ zoo | |

| Total samples | 68 |

| Samples with at least one successful dump | 63 |

| Injected code extractions | 41 |

| New processes dumped | 31 |

| Kernel modules dumped | 4 |

| Total storage used | ~200 MB |

Table 2: Statistical information regarding the results of running samples from a malware familites zoo through VolatilityBot.

In this subset we see an even higher success rate. The tested samples were malware of several different categories: downloaders, financial malware and targeted malware. The analysis output provided indicators such as strings and YARA signatures which focus in-depth analysis on the relevant and significant parts of the malware.

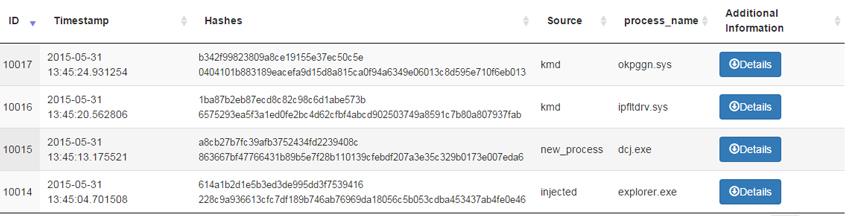

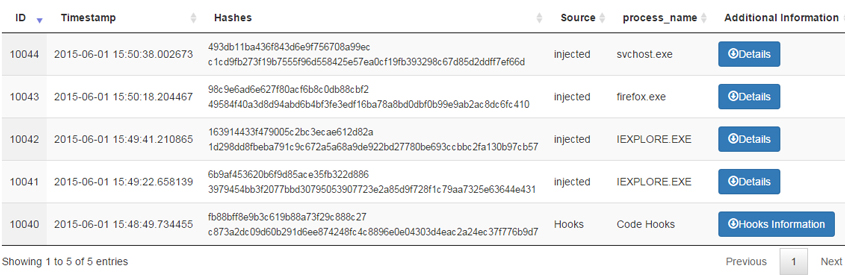

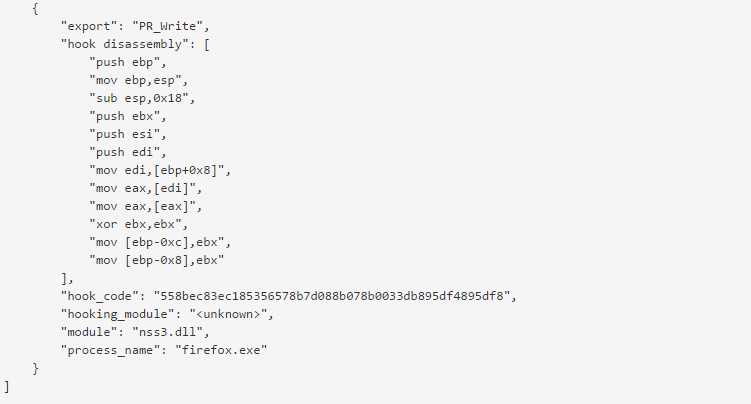

To illustrate VolatilityBot’s versatility, Figures 2, 3 and 4 show a few examples of successful extractions.

Figure 2: A sample that loaded a kernel driver.

Figure 2: A sample that loaded a kernel driver.

Figure 3: A sample that injected into all browsers.

Figure 3: A sample that injected into all browsers.

Figure 4: Hook disassembly.

Figure 4: Hook disassembly.

VolatilityBot is still a work in progress, and it’s not perfect. The following are some of the weaknesses I have found during my research:

There are a lot of ideas and directions for the future development of VolatilityBot a researcher can choose in order to use VolatilityBot for his/her own research:

VolatilityBot can be used in two different modes:

The VolatilityBot daemon runs in the background and looks in the database for malware samples awaiting analysis

New samples can be submitted using:

python VolatilityBot.py –e –r –filename ~/samples_folder

The daemon itself is executed using:

python VolatilityBot.py -D --sleep 60

VolatilityBot is executed, and once the analysis queue is empty, it will exit and display a summary with statistics:

A. Single file – a single file to be processed (60 seconds timeout):

python VolatilityBot.py –filename ~/sample.exe --sleep 60

B. Folder – submit a folder containing PE files (recursive) and create a work queue:

python VolatilityBot.py –r –filename ~/sample_folder –sleep 60

C. Submit a folder while skipping existing files in the database:

python –r –s VolatiliotyBot.py –filename ~/sample_folder –sleep 60

D. Re-submission of failed files (according to the status in the database):

python –Q VolatilityBot.py –sleep 60