2016-01-01

Abstract

Tech support scams have been around for a long time, and despite all the attention they have received, they are only getting worse. Scammers are diversifying - no longer just using the Microsoft cold-calling technique but now also using deceptive ads and pop-ups, phishing scams, and even targeted campaigns for special events. Documented instances also show that while ‘scanning’ the computer for viruses, the crooks scrape any personal documents they can lay their hands on, opening the door for serious identity theft problems. In his VB2014 paper, Jérôme Segura looks at how tech support scamming has evolved.

Copyright © 2014 Virus Bulletin

Tech support scams have been going on for a long time, and despite all the attention they have received, they are only getting worse. The classic fake Microsoft cold call is no longer the only technique used, as it is far more effective to have marks call about an existing problem.

Scammers are diversifying, using deceptive ads and pop-ups, phishing scams, and even targeted campaigns for special events.

As the scam gets more sophisticated (Mac OS and Android are on their list too), the risks for potential victims have increased as well. Documented instances show that while ‘scanning’ the computer for viruses, the crooks scrape any personal documents they can lay their hands on, opening the door for disastrous identity theft problems.

In this paper we will look at:

Cross-platform and across countries scams: not just a Windows problem anymore. Mac and Android users are on the radar and calls are also coming from the US.

‘Themed’ scams: why and how the crooks come up with new twists.

More than a single repair fee: scammers will not want to waste too much time once they have been paid. Worse, they may install malware, and even steal your personal documents.

Intelligence gathering: how to build a honeypot to capture the scammers’ location, their scripts, etc.

The backend: pinpointing how these people are organized, putting them on a map and following the money trail.

Most of us have received, or at least know of someone who’s received an unsolicited call from ‘Microsoft’. The experience is usually quite colourful, punctuated with claims of ‘your computer is infected’ and ‘hackers have infiltrated your network’, which are aimed at scaring the victim. For those who fall for the scam, the cost of ‘fixing’ these issues is usually steep, and in some cases more than the value of the computer itself.

While still ongoing, these unsolicited calls are no longer the only method by which cyber crooks attempt to sell worthless support packages. In order to keep their conversion rates up, scammers are attempting to drive their marks to them, investing heavily in online ads, widening their scope in operating systems and platforms, and in some cases going even further with destruction of property and identity theft.

This paper is a continuation of the work previously carried out by other researchers, in particular by David Harley, Martijn Grooten, Steven Burn and Craig Johnston, who presented their work at the 2012 Virus Bulletin Conference [1].

Scammers, just like any other cybercriminals, are interested in achieving the best return on investment, and typically that means going after the lowest hanging fruit first.

Because Microsoft Windows has had the largest market share in the PC business for many years, it simply made sense, initially, to target those users and leave the rest alone.

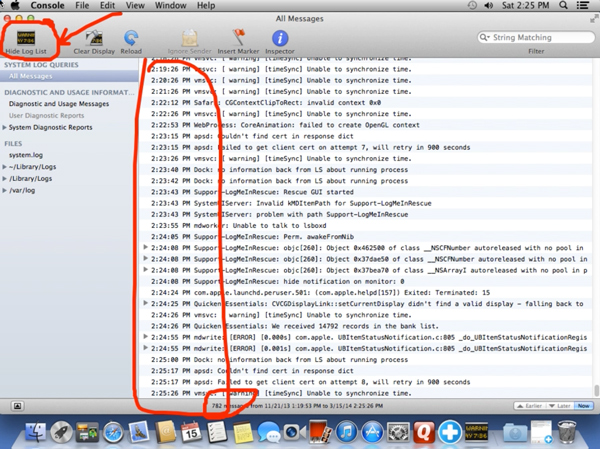

There are many features [2] within Windows that can be utilized for very different purposes. The classic example is probably the Event Viewer, which contains system logs and is often abused. It is easy for crooks to claim that normal reporting messages are in fact critical errors or viruses – something that seems perfectly plausible to the non-savvy user.

However, the market has changed in recent years. We are seeing an increase in scams targeting Mac users and, more notably, mobile platforms (namely Android). In the past, when scammers were cold-calling or enticing users to call them, they would generally not pursue their pitch if the user was not running Windows. But this is no longer always the case.

For years, there has been a theory that Macs are safe from viruses and malware. If we look at the numbers, there is indeed more malware for Windows than for Mac OS – something that can in part be explained by the market share argument discussed above.

The feeling of being more secure because you are running a Mac can actually leave you less prepared for the unexpected. It’s worth noting that social engineering works best when the mark has already let his guard down.

From the scammers’ side, they can simply switch the ‘We are calling from Microsoft’ to ‘We are calling from [insert Internet Service Provider name here]’, and all of a sudden it’s irrelevant which computing platform the victim is running.

The majority of the remote access programs (TeamViewer, LogMeIn, etc.) used by scammers to control your computer also have a Mac version that is just as easy to download and use.

While Windows offers a great variety of tools to make false allegations about your computer’s security and stability, it does not take too long to find equivalents on Mac OS [3]. We will review a few that are often used.

The Mac’s Console can in many ways be compared to the Windows Event Viewer: it is a log viewer that contains a continuous stream of events, all of which can seem very obscure to the uneducated user.

While useful to diagnose system errors or program crashes, the Console is also the perfect tool for a scammer to make up non existent issues such as an imminent system crash or viruses multiplying.

The ping command is often used to test if a hostname or an IP address is reachable. Many system administrators will use a Ping to test if a machine is properly connected to the Internet. What crooks are after is the error message you receive when the test fails:

$ ping protection.com PING protection.com (72.26.118.81): 56 data bytes Request timeout for icmp_seq 0 Request timeout for icmp_seq 1

In the Ping test above, the domain in question did not accept ICMP requests, and therefore would always return a ‘timeout’ error.

That alone is enough for scammers to claim that your Mac does not have any protection software installed.

Netstat is another command used by IT admins that shows, amongst other things, network connections. Typically, if you are connected to the Internet and your browser is running, a table will show the protocols, and local and foreign addresses. Scammers will tell you that the foreign addresses belong to hackers that have infiltrated your network. They will also point out the ‘ESTABLISHED’ connection status, which they will say means that bad guys are currently and actively stealing all your information.

Mac users may have less to worry about in terms of malware than their Windows counterparts, but the threat is still there, and growing. It is no different with tech support scams. While perhaps you might get lucky with some crooks that haven’t updated their scripts yet, the reality is that such scams are likely to happen increasingly frequently.

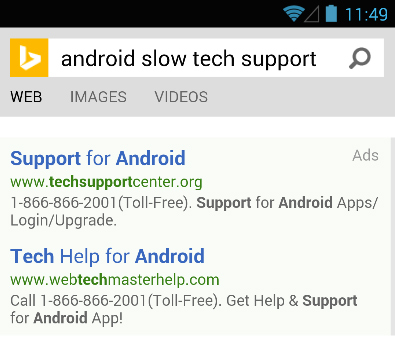

The mobile platform is vastly different from the Windows and Mac operating systems. Also, the idea of a remote login into your phone is still a little bit odd (although technically feasible). What is also interesting to note here is the fact that cold calls typically occur on landlines as opposed to mobile phones.

But for some rogue tech support companies, this is not a problem at all. In fact, they will even spend money on advertisements to drive traffic to their websites, with headlines such as ‘Phones and tablets issues. Tech support just a call away.’

It seems the reliance on a laptop or desktop is still very strong, because rogue support agents will often ask you to plug your smartphone or tablet into your computer so they can ‘scan’ it [4].

The so-called scan will typically revolve around trying and failing to open files with unknown extensions or attempting to create files on read-only media.

If, for some reason (which happens more often than not), your computer does not have the proper driver to access your mobile device’s storage, the scammers will go back to their bread-and-butter claim that ‘your network is infected’. They’ll ask you if you use your device on your network, for example through Wi Fi (which you probably do). The next step is to convince you that anything going through your Internet connection is malicious, and that only a Cisco-Certified Network Engineer can help you fix that.

Tech support scams on mobile devices are still in their infancy, but we can expect them to become more popular, and also to be used without the need for a PC.

The majority of tech support scams originate in India, where the labour force is cheap, the population speaks English, and it is a location that is used to providing support all over the world, regardless of time zones.

But the business of what some call ‘Premium Tech Support’ is a million-dollar industry that many software companies simply cannot ignore. Case in point, a company can either sell a registry cleaner for $29.99, or also upsell the customer to a nice $399 support plan. Sadly, the sales pitch often gets dirty and you will see US agents reuse the same tricks and lies as their Indian counterparts.

The growth of fraudulent US-based tech support is an interesting phenomenon because it has a direct advantage over the India-based ones. Many people are careful or less eager to engage with a person that has a deep Indian accent, but would feel at ease with someone sounding just like them. Also, US tech support companies tend to be better organized, usually have more professional-looking websites, as well as better sounding call centres (some Indian boiler rooms are so loud you can barely understand anything). Fortunately, though, if the company is based in the US, it is much easier to go after and local authorities can prosecute using more rigorous legislation.

Themed tech support scams are just an evolution of the classic Microsoft scam. They show a will to diversify the bait to reach out to more people. You may have been told to be aware of fake calls from Microsoft, but if the call is from a different company you may well be caught off guard.

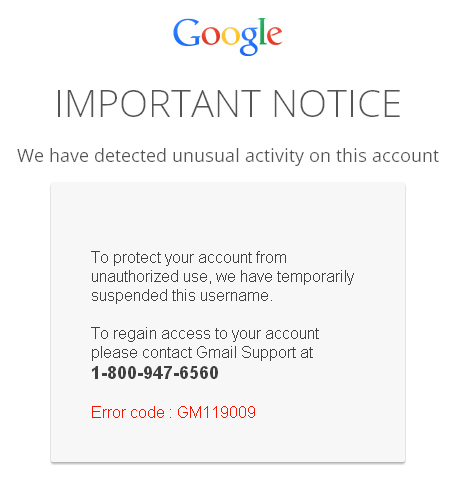

In a new twist, a group of scammers created an elaborate Netflix phishing page [5] with a double purpose:

To collect email addresses and passwords.

To trick people into calling for assistance.

Here is how it works: you receive an email or get a pop up asking you to sign into your Netflix account, click on the link and type your email address and password into a fake login page. Instead of being signed in, you get an error message informing you that your account has been suspended.

This is just the beginning of your troubles because when you call the support number to restore your account, you are not talking to real Netflix agents, but rather to ill-intentioned support crooks. What follows next is the typical pitch about your computer being hacked (the alleged reason for your Netflix account being suspended) and, of course, expensive fees to resolve the ‘issue’.

This approach combines both phishing and tech support scams into one – something that is interesting on many levels. Charging money for bogus services is one thing, stealing user credentials is another. This is a step towards a more malevolent behaviour, one of many that we will expose later.

The themed scams are growing in popularity and targeting major brands such as AOL, Comcast, Gmail, etc. with elaborate phishing schemes [6].

Scams don’t just happen out of the blue. They are often linked to current events or circumstances that make them more relevant and believable. This next example was recorded during the dreaded tax season, when everyone is trying to get their accounts in order and file their taxes before the deadline.

Many people use professional accounting software, and for one reason or another may run into issues. For example, you might have saved an important Quicken file, but can’t remember the password. After hours of frustration, you may start looking for help online and could very well run into an ad that offers to solve your problem.

Before you know it, a remote technician has taken control of your computer and, after a quick look at your accounting software, drifts back into the typical story of hackers having compromised your machine [7].

With no shame, the technician will write out your bill in a text editor as follows:

QUICKEN SOFTWARE: $149.99 REPAIR: MAC CERT ENGINEERS 1 yr warranty... any issue... 2 hours... call you back... block the ways... $299.99

Perhaps the most disturbing thing of all about this case was that the company itself was registered to a certified QuickBooks ProAdvisor [8], a sign of trust that could cause people to let their guards down.

Now you are dealing with individuals that have just lied to you and hold your financial data in their hands. This is a delicate position to be in and hard to get out of. If you change your mind and refuse to pay, the scammers could hold your computer to ransom [9].

It should not come as a surprise that the ‘work’ performed by these tech support companies reflects the quality of their initial diagnostics. One might wonder why they even want to stick around once they have their money.

Not all tech support scammers are the same though, and as strange as it sounds, some actually try to provide some sort of a service. This isn’t from the goodness of their hearts, of course. They do have incentives in the long run to appear somewhat legitimate. In fact, certain companies go to great lengths to address any complaints that might affect their Better Business Bureau rating and to post positive testimonials on social media sites. At the other end of the spectrum, some companies will cross the line into pure cybercrime and extortion.

While the technician may sell you a full support package that includes an unlimited number of calls, it is in their best interest to minimize their costs and get you out of the way as fast as possible. Other than the man-hours, they will not want to waste any extra on applications or upgrades for your computer.

In some cases, the fix consists of removing temporary files using the built-in Windows Disk Cleanup utility. Often, the technician will download free software such as Malwarebytes Anti-Malware (violating the End User Licence Agreement) to detect and remove potential malware.

All in all, this type of clean-up takes less than an hour and does not require the skills of a Microsoft Certified Technician. It may have some value for certain users though, so long as the technician sticks to using built-in tools and doesn’t step out of his area of ‘expertise’.

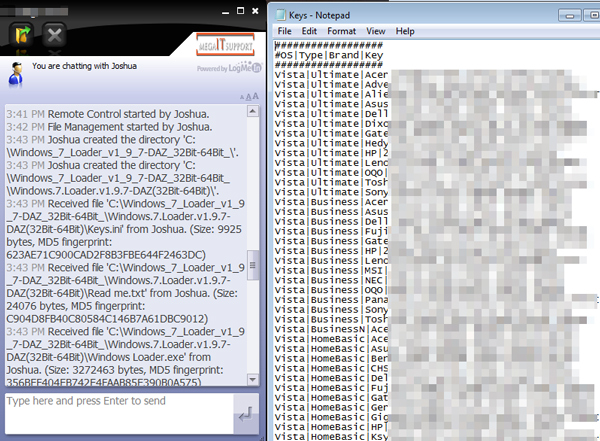

When the promise of fixing your outdated computer includes paying for software upgrades, scammers will find alternative solutions.

Unbelievably, you will watch the technician download keygens [9] and other software cracks right in front of you. That is, if you chose to wait around, as often you are told to let them do the work and come back later.

Not only is this completely illegal, but it is also very dangerous seeing as many such programs may contain trojans and other pieces of malware [8]. In essence, the technician is acting like a teenager who doesn’t want to pay for his games and tries to crack them – except that he’s supposed to be a qualified professional.

Unsurprisingly, some machines (or customers) will give the technician more grief, and he may start getting frustrated. There are many recorded instances where the tech guy simply can’t put up with it anymore and will start lashing out, using foul language and going on a rampage, deleting your personal files, removing software drivers, and even locking you out of your computer [11].

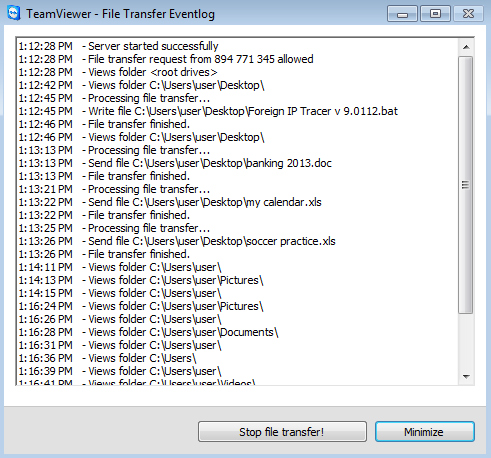

Occasionally, the technician, who has full access to your machine, may start snooping around for interesting documents. To facilitate this task, many remote control programs have a built-in file transfer feature, much like FTP, that allows the scammers to upload all your files to their own computers for later viewing.

Sometimes the technician might want to browse your files in privacy and make sure you are not watching. Interestingly, a feature that enables this is available in certain remote programs; at least TeamViewer has one called ‘Show black screen’ [12]. Your computer screen turns black, but the scammer still has full access to it and can now open folders and documents without you seeing.

But identity theft is not limited to the technician stealing your files. Many companies do not have a secure payment processing website, and some don’t even have a website to take payments at all. Often, you’ll end up typing your credit card number into Notepad or the chat window.

On one particular occasion, I was asked to scan my credit card and driver’s licence and send the scammers the pictures. Why? Because apparently ‘there are many untrustworthy people on the Internet’ – something which struck me as a little ironic considering they were the ones pulling the scam.

Contrary to the initial sales pitch, registering for the tech support service is not going to solve your computer problems, in fact quite the opposite. The truth of the matter is that you can’t really predict what is going to happen, but either way it’s not going to end well.

As we’ve seen, tech support scams keep evolving and taking unexpected turns, while the number of victims is growing. For this reason, it is important to keep an eye on their development and be prepared to act when new information is discovered. But unless you are well organized, many of the important details might just slip by, and you’ll have wasted your time and energy in vain. The next section presents some ideas and tools for researchers and enthusiasts so they can be prepared to spring into action and make valuable contributions to the security community.

Please note that this is not an invitation to go after scammers, and that you would be doing this at your own risk.

First, you will need a computer or virtual machine dedicated for this purpose. A VM is recommended for its ease of use and containment from malware or other network-related threats.

Here are some general guidelines for setting up your environment:

Install Windows 7 or 8 with popular software (Skype, Adobe Reader, Microsoft Office), as well as some games. Do a bit of browsing, add bookmarks, add a cool-looking wallpaper and essentially make it look as if this is a regularly used machine.

Harden your VM (remove guest additions or VMware tools) so it cannot be detected as a virtual system. Scammers have learned and are now checking msinfo32 for BIOS information. You can change it in VirtualBox [13] and VMware.

Apply all Windows and other software updates. Your machine should also be free from malware. Install the recommended security products from Microsoft (i.e. MSE); turn the firewall and automatic updates on. The idea is that if the machine is clean and fully working, the technician will have to lie in order to make the sale.

Install your own version of the remote desktop software. The standalone versions the scammers send you often do not have all the logging and tracking features.

Place strategically named bait documents on your desktop that will alert you if opened on a different machine.

Create multiple identities that you will play along with. These should include:

A first and last name, and physical address.

An email address.

A new and unique phone number (choose your area code carefully).

The choice of the phone number is crucial because you certainly do not want scammers to harass you on your real number. Keep in mind that the phone number will most likely be for a one time use only, as it is usually recorded and can be shared across scammers. There are many apps that allow free VoIP calls with a dedicated number (stay away from Google Voice as it can easily be detected with caller ID).

Finally, you will want to document your findings, and for that purpose you should set up an external video recording program that will capture your screen and also catch the audio from your phone.

At this point, you have created a honeypot [14], but that is only half the battle – the next step involves personal skills in reverse social engineering.

Before entering the session you should be certain that you are well prepared and that you have set up your objectives. What would you like to achieve? How are you going to go about it? What is your time frame?

As you can see, this exercise requires a good methodology and should be taken seriously. Many people ‘troll’ tech support scammers, wasting their time or saying profanities. However, there are much better ways to go after them.

It’s not unusual to feel a little apprehensive about talking to cyber crooks, but you can use those emotions to your advantage. Remember that you are pretending to be a distressed user in need of help.

The following are some suggestions for actionable information you may want to seek:

Get them to lie on record. In case they’re trying to stay vague on purpose, ask for a virus scan, make them label their findings using definite words such as virus, infections or malware.

Confirm with them their business name, website(s), phone number(s).

Identify their real IP address.

Typically, the first thing the scammers will want you to do is to go to a website to download the remote desktop program. If you already have a copy installed, pretend you are following the instructions but instead fire up your program and then give them the ID and password.

You may need to collect evidence on the fly, as scammers are likely to erase their tracks at any time. The easiest thing to do with a VM is to take snapshots during the call. Sometimes taking a snapshot will briefly pause the VM, but most remote programs are set to auto reconnect.

Once you have collected the information you need, make a clean exit. The technician’s job is to make you buy the service right at that moment, not in an hour or tomorrow. Your job will be to find an excuse to delay, postpone or simply turn down his proposition without raising suspicion that you were undercover.

Once the call is finished you can start putting together all the pieces of evidence you have gathered. The VM’s snapshots should be considered dirty and eventually discarded. Organize screen captures, video recording and other important files by name and time stamp and save them for future use. Note that the amount of data can be overwhelming and you may need additional or external storage.

In some cases it might be useful to collect the remote software’s session ID (the number you gave the scammers so they could connect). Some companies license the software, and reporting them using that ID could lead to sanctions or even termination of their account.

The scammers will almost always say that they are located in the US, either west or east coast. We all know that this is false, but can’t always prove it.

Finding their actual IP address would reveal their exact location but unfortunately that is not always easy to do. As mentioned earlier, certain remote programs bounce through a proxy (usually in the US), will not create any log file for the session or will delete any logs when the session is terminated (a problem the author brought up with one software company [15]). Having said that, there are still ways to collect the IP address and we will review a few.

Check log files and parse them for the IP address. The log format will vary based on the application. Here are some examples for two of the most popular ones.

LogMeIn:

2014-01-31 14:01:19.791 - Debug - Service - Socket - 216.52.233.134:443 - Assigned remote address: 203.122.{redacted}:63631TeamViewer:

2014/01/30 15:47:11.212 1128 3920 S0 CT12 GWT.CmdUDPPing.PunchReceived, a=122.162.{redacted}, p=16874Bait documents should be designed to tempt the scammers into stealing your files. Take Finances 2014.docx, a Word document that looks intriguing and perhaps contains account numbers or banking details. In many cases, this will trigger curiosity and at best the desire to silently take it. However, once the scammer opens the stolen file on his own machine, the document will beacon to an external server and send an alert. You can create your own booby-trapped files or use online services such as HoneyDocs [16] to generate them for you. Note that the files are totally harmless (no malware) and you should leave it up to the scammer whether or not he is going to grab them from you.

If the sting was successful, you will receive a detailed alert including the IP address, latitude and longitude from which the document was opened.

If all of the above failed, perhaps you had done your own bit of reverse social engineering. While playing the victim is somewhat easy, going on the offensive and trying to con the con artist is a different affair. If you do it well though, and are persistent, you can actually make the scammers do certain things that are slightly outside of their comfort zone, giving you a chance to identify them.

You can learn an awful lot about individuals or companies from social media sites. Many people tweet or post an update on Facebook using their actual location, or you can deduce it from the pictures they upload (either with the actual content or EXIF data).

This one suggests that you are actually going to give the scammers money – something that we would not recommend at all. You can, however take it as far as you can without going all the way. It’s quite interesting to identify the payment options and payment processors involved. In some cases, companies will rely on legitimate e-processing sites, and you can easily snag the company’s ID either in the URL or in the customer form.

In other cases, payment will have to go through PayPal or Western Union, so your chances of collecting actionable intelligence decrease drastically.

Regardless, sometimes little bits of information can still help to build a case and are evidential data for law enforcement agencies.

Tech support scams are here to stay, at least in the near future. The efforts that have been put into finding new ways to go after people show that this is a real and lucrative business. But in order to keep it profitable, you also need to invest in advertising, and compete with others.

The classic Microsoft cold-call scam is still going on and will probably continue for the foreseeable future. It is a cost effective technique that is good enough for new scammers on the market. But it is also a very wasteful approach and produces mixed results. Better-organized companies will target their audience and find the right angle to go after. It’s quite possible that a handful of well-funded companies will dominate this business and squash their competition.

Another aspect of the tech support scam not mentioned in this paper is the breakdown in the chain of actors and tasks. So far, almost all of the companies we have observed have done everything in the process: lead generation, sales and technical support. In the future was can envisage companies that specialize in fraudulent lead generation (affiliates) and sales but that outsource the actual work to India where labour is cheap. This would be the best of both worlds: native speakers to do the hard part of social engineering, and a cheap and available workforce to do the rest.

In the meantime, the fight against tech support scams continues. There are many ways to tackle this problem and rather than listing all of them here, we’d rather share a link to a resource page [17]. It is worth mentioning that a coalition against malicious and misleading ads, called TrustInAds.org [18], has recently been formed. This is a great initiative that will directly affect the scammers’ ability to reel in more victims by cutting down on their leads.

The author of this paper would also like to see the creation of a centralized database where independent researchers, victims and anybody interested in the subject could report information that would then be able to be cross-referenced. To keep pace with the scammers, we also need to be organized and work together.

[1] Harley, D.; Grooten, M.; Burn, S.; Johnston, C. My PC has 32,539 errors: how telephone support scams really work. http://static2.esetstatic.com/us/resources/white-papers/Harley-etal-VB2012.pdf.

[2] Segura, J. Malwarebytes. Tech Support Scam Resource page, Tricks. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/tech-support-scams/#tricks.

[3] Segura, J. Malwarebytes. Tech Support Scams: Coming to a Mac near you. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/fraud-scam/2013/10/tech-support-scams-coming-to-a-mac-near-you/.

[4] Segura, J. Malwarebytes. Tech support scammers target smartphone and tablet users. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/fraud-scam/2014/01/tech-support-scammers-target-smart-phone-and-tablet-users/.

[5] Segura, J. Malwarebytes. Netflix Phishing Scam leads to Fake Microsoft Tech Support. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/fraud-scam/2014/02/netflix-phishing-scam-leads-to-fake-microsoft-tech-support/.

[6] Segura, J. Malwarebytes. Netflix-themed tech support scam comes back with more copycats. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/fraud-scam/2014/04/netflix-themed-tech-support-scam-comes-back-with-more-copycats/.

[7] Segura, J. Malwarebytes. The Tax Season Tech Support Scam. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/fraud-scam/2014/03/the-tax-season-tech-support-scam/.

[8] Intuit. QuickBooks ProAdvisor Program. http://proadvisor.intuit.ca/professional-accounting-software/index.jsp.

[9] Popken, B. NBC NEWS. Netflix Customer Service Impersonated by Scams in Google and Bing Ads. http://www.nbcnews.com/business/consumer/netflix-customer-service-impersonated-scams-google-bing-ads-n82346.

[10] VirusTotal. Scan results for keygen. https://www.virustotal.com/en/file/34cc664c49873468b5606d55795a39e83d15e37e7051cdd580569fd5987ea962/analysis/.

[11] Feinberg, A. Gizmodo. The Scam Hunter: What It’s Like to Track Internet Bad Guys For a Living. http://gizmodo.com/the-scam-hunter-what-its-like-to-track-internet-bad-gu-1563306488.

[12] TeamViewer. User manual. http://www.teamviewer.com/en/res/pdf/TeamViewer9-Manual-RemoteControl-en.pdf.

[13] VirtualBox. Configuring the BIOS DMI information. http://en.helpdoc-online.com/virtualbox_4.1.2/source/ch09s12.html.

[14] Spitzner, L. Honeypots. http://www.tracking-hackers.com/papers/honeypots.html.

[15] LogMeIn, Inc. Twitter. https://twitter.com/LogMeIn/statuses/431560869751697408.

[16] HoneyDocs. https://www.honeydocs.com/.

[17] Segura, J. Malwarebytes Tech Support Scam Resource page. http://blog.malwarebytes.org/tech-support-scams/.

[18] TrustInAds.org. http://trustinads.org/.

[19] Harley, D. AVIEN. http://avien.net/blog/pc-support-scam-resources/.

[20] Microsoft. Avoid tech support phone scams. http://www.microsoft.com/security/online-privacy/avoid-phone-scams.aspx.

[21] Wikipedia. Technical support scam. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technical_support_scam.