2015-09-24

Abstract

On September 12-13th 1991, some 150 delegates and 20 speakers from four continents assembled at the Hotel de France in St. Helier, Jersey for the first International Virus Bulletin Conference. VB's then editor Ed Wilding provided a full round-up of the event, looking at the themes, the presentations, the discussions and the Donald Duck impersonations.

Copyright © 2015 Virus Bulletin

(This article was first published in Virus Bulletin in October 1991.)

In a break with tradition, this month VB tentatively introduces some photographs into its editorial. These pictures were selected from the hundreds of snapshots taken at the First International Virus Bulletin Conference held last month on the Channel Island of Jersey. On September 12-13th 1991 some 150 delegates and twenty speakers from four continents assembled at the Hotel de France in St. Helier, Jersey. Before expanding upon the themes of the conference itself it is the editor’s beholden duty to say thank you to:

the delegates: a formidable and eminent audience.

the organisers: the supremely efficient team of Petra Duffield, Karen Richardson, Lynne Whitehead and Sarah Hood.

the speakers: who prepared their presentations with great care and, in many cases, had to travel thousands of miles to attend.

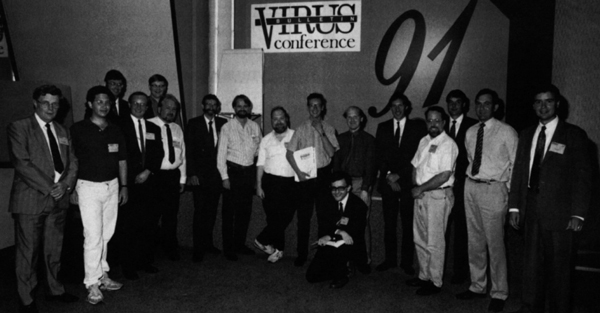

Figure 1. The ‘A’ Team. (Left to right) Jim Bates (Bates Associates, UK), Ross Greenberg (Software Concepts Design, USA), Richard Kusnierz (Network Security Management, UK), Dr. Jan Hruska (Sophos, UK), Fridrik Skulason (Technical Editor, Virus Bulletin, Iceland), Detective Constable Noel Bonczoszek (City & Metropolitan Police, UK), Joe Norman (SGS-Thomson, UK), Steve White (IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, USA), Prof. Eugene Spafford (Purdue University, USA), Edward Wilding (Virus Bulletin, UK), Vesselin Bontchev (University of Hamburg, Germany), David Ferbrache (Defence Research Agency, UK), Dr. Simon Oxley (National Power, UK), John Norstad (Northwestern University, USA), Scott Emery (Digital Equipment Corporation Inc., USA), Squadron Leader Martin Smith MBE (Touche Ross Management Consultants, UK), Ken van Wyk (CERT, USA).

The single loudest appeal from delegates at this conference (nearly all of whom were from commerce, industry, government or military organisations) is that the anti-virus community (if such exists at all) must start to see the wood for the trees, i.e. a wider perspective on this problem is required. To paraphrase Steve White of IBM: ‘We all of us know how to protect one computer from rogue software, the question is how do you protect a whole user community?’ Anti-virus software developers, in addition to providing diagnostic tools must start formulating complete, even bespoke, strategies for their customers and provide training and consultancy. It is now evident that corporate end-users of defensive software (or hardware) are increasingly demanding an augmented service from suppliers. (Incidentally, many software developers were present including representatives from Central Point, Symantec, Software Concepts Design, Sophos, Cybec Pty and BRM Systems.)

There was evident criticism of the research community for failing to identify and explain the essential technical trends which will inevitably affect long-term defensive strategies. Explaining the redundancy of certain worn-out and ineffectual technologies to management is extremely difficult. Outlining the limitations of obsolescent techniques (as opposed to obsolete methods) is even more difficult. Software ‘solutions’ are often rushed into effect without sufficient care and planning, only to be discarded at a later date (often following considerable financial outlay) due to their unsuitability.

These general criticisms will start to be redressed by VB in the coming months. The general message appears to be to keep the journal practical and balanced (between the technical and managerial) and, at all costs, avoid the more futile academic exercises to which the subject of computer viruses so often gives rise.

A not entirely unexpected message from the conference is that the corporate technician or manager is not interested in such ethereal concerns as bit changes in memory or minor code variations or modifications. This is unfortunate because the research community is currently fascinated by such things. Interestingly Detective Constable Noel Bonczoscek of New Scotland Yard intimated that without such precise identification methods, his job of collating and presenting evidence would become impossible. A conflict of interest is readily apparent.

IBM provided the most intensively research-based presentation of the two days. Studies have been undertaken at the T. J. Watson Research Center in New York State into the spread of different virus samples worldwide. In common with the findings of Virus Bulletin (VB, September 91, p. 14) IBM’s statistics show that a few viruses account for the most incidents - the New Zealand (Stoned) virus accounting for approximately 28 percent of all incidents. The ‘promiscuous software society’ alluded to by the ‘virus industry’ is proving to be a myth - software sharing is invariably localised and limited. Those theoreticians who talk of epidemics, universal contagion and the end of personal computing, take note!

Central reporting of incidents, diagnostic software and immediate response (the essential components of a defensive strategy) are proven as the most effective anti-virus approach. IBM’s research staff are currently automating the development of virus-specific detection software - results from these experiments put VB’s attempts to provide reliable search patterns to shame. IBM minimises false positive indications with the use of a vast library of user supplied software running into gigabytes. To quote Steve White: ‘In a company with 250,000 PCs, a single false positive can mean three days solid tied to the telephone.’ White warned against the term ‘exponential’ - nothing that his team has observed in the virus field comes close to being exponential.

The most original (and complex) paper was provided by Yisrael Radai of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Radai contends that cryptographic checksumming employing DES or an ISO standard algorithm is effectively ‘overkill’ for managing the computer virus threat. The CRC algorithm is just as effective as well as being easier to implement and far faster in its execution.

According to Radai, the confusion on this point arises from the cryptographic obsession with confidentiality; CRC is more vulnerable to cryptographic attack than DES but this point is irrelevant when choosing an integrity checking algorithm to counter indiscriminate computer virus infection.

Joe Norman of SGS-Thomson described the corporate anti-virus strategy which he has devised. He insisted that detection software must be compatible with the nomenclature and terminology adopted by VB so that information can easily be cross-referenced.

Describing an initial integrity check at one site where 4,000 hard disks and diskettes were scanned, he reported that some 2 percent were found to be infected.

A video covering computer virus prevention had been adopted for educating employees - this had proved effective but has also been costly in terms of time (5,000 users x 1 hour for each employee’s induction works out at about 2.5 man years in total).

Norman cautioned security managers against Draconian disciplinary measures. He would rather have a virus incident reported than have some non-technical end-user attempt to disinfect the machine and subsequently compound the damage. (This new ‘softly softly’ policy is a total reversal of the ‘hang ‘em and flog ‘em’ tactics of yester-year.)

Figure 2. After-dinner speaker and associates half-way into disassembling the notorious two-byte virus. Back row (left to right): Petra Duffield (Virus Bulletin), Karen Richardson (Sophos), Wing Commander Amanda Butcher (Ministry of Defence, UK). Front row: Lynne Whitehead (Oxford University), Squadron Leader Martin Smith (Touche Ross), Julie Hollins (WH Smith News).

Dr. Simon Oxley of National Power reiterated this theme: ‘We don’t want to drive this problem underground. It’s common to be over-zealous and publish policies which threaten instant dismissal for anyone found infecting a PC with a virus. A better approach is to encourage rapid and full notification of suspected virus problems without the threat of retribution. Incidents can then be diagnosed and dealt with correctly.’ Severe disciplinary measures should be reserved for instances where there was flagrant disregard for procedures or the deliberate introduction of a virus.

Oxley also alluded to the economics of virus protection:

‘A quick back-of-an-envelope calculation can be done for a company with around 1000 PCs. An initial reaction might be to equip all these PCs with a commercial anti-virus package. This might cost £50,000 at £50 per PC. The package could be invoked on every PC boot to carry out a check or a scan lasting maybe one minute. If each PC is booted once a day we are spending 16 hours (two man-days) every day checking for viruses, at an average cost in lost time of perhaps £200. During the first year of operation, this mechanism will therefore cost £100,000. In addition to this we have the cost of training users and support staff in the use of these packages and this too could be considerable.’

Vesselin Bontchev provided an insight into the Bulgarian ‘virus factory’. A disillusioned army of programmers trained by the communist regime to break software copy-protection schemes had turned its attentions to virus writing. The low-level programming methods (sometimes described as ‘on-the-metal’ programming) involved in copy-protection were readily adaptable to the development of virus code.

Some 80 Bulgarian viruses are causing disruption within Bulgaria itself. According to John McAfee approximately 10 percent of all infections in the USA are caused by Bulgarian viruses.

Jim Bates discussed the process of virus disassembly - not an easy task within the time frame of forty-five minutes. The vital point (and one to which many virus writers seem entirely oblivious) is that any functioning computer program can be reverse engineered back to its original (human intelligible) instructions which can then be analysed to determine its actual functioning. (Ross Greenberg re-emphasised this point ‘All viruses can be disassembled. If a CPU can do it - and it must in order to run the virus - then a human can do it, too, albeit slower and usually with a good deal more foul language.’)

Bates covered the essential tools and steps necessary to the task. Less obvious requirements were copious quantities of coffee and cigarettes, insomniac colleagues who could assist with technical enquiries at three o’clock in the morning and a wife (or husband) with the patience of a saint.

The major threat at the moment was the dissemination of source code: ‘If object code is a bullet then virus source code is a loaded gun!’ Having immersed himself in virus disassembly for nearly four years Bates concluded: ‘The more experience you gain, the more you realise just how much you don’t know’.

Figure 3. Gala Dinner. Delegates Esther Armbrust (BASF AG) and David Henretty (Apricot Computers) demonstrate static analysis and dynamic decompression utilities.

Ross Greenberg, discussing MS-DOS anti-virus tools and techniques, described his dismay each time he reads the dreaded entry ‘no search pattern is possible’ in the VB Table of Known IBM PC Viruses. ‘It means that antivirus researchers have to stop attacking each other in public forums and actually get to work.’ Encryption and ‘armour’ were obstacles, but never proved insurmountable. ‘The best news is that it’s not always necessary to disassemble the full virus in order to detect it, disable it, inoculate against it, or even disinfect a file.’ Greenberg concluded that the public will continue to misuse the defensive tools at its disposal.

John Norstad, author of the widely used Disinfectant anti-viral utility provided an introduction and overview to the Macintosh virus problem. Macintosh users are far fewer than those of IBM PC compatibles (there are approximately three million Macs in use compared to some fifty million PCs), which means that the user community is relatively closer and more united. Certainly there is none of the bickering, infighting and political intrigue currently prevalent in the PC anti-virus industry. Norstad described an extraordinary situation on the Macintosh whereby the nVIR virus interbreeds and spawns different generations of offspring. Watching this process in action led to an ‘uneasy sense of voyeurism’.

Ken van Wyk of the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) addressed network security, specifically referring to the Unix environment. Van Wyk is responsible for issuing security advisories for Internet users (some half a million hosts combine to make the Internet the largest network in the world). There are political considerations inherent to such a sensitive role - tact and diplomacy are essential when dealing with system vendors and users as diverse as the military and academia. One vital consideration when threatened by system intrusion is to keep the catalogue of known and existing vulnerabilities off-line!

Professor Gene Spafford (Purdue University, USA) successfully demolished the common misconception that Unix as an operating system is insecure - users had grown to expect openness and convenience. As with all computer systems, ‘user friendly’ can mean ‘attacker-friendly’. Configuration controls are available under Unix but implementing them was liable to trigger a wave of protest among users familiar with an unrestrictive environment.

David Ferbrache of the UK’s Defence Research Agency demonstrated that traditional Orange Book methods were wholly inadequate to countering the virus problem. The US Department of Defense Orange Book was principally concerned with confidentiality whereas viruses impact upon integrity and availability. Malicious software introduced at an untrusted level is likely to be executed by users with restricted or even full system privileges.

As with any conference, much of the real work was conducted away from the bright lights of the conference hall and in the darker recesses of the bar. Over pints of beer, a number of informal arrangements were agreed between various researchers and agencies. The priority among the anti-virus community is to cut incident response times, increase cooperation, the sharing of binary code, disassemblies and tools. The means and methods to accomplish these objectives are agreed.

Informal cooperation will be the key to the success of this initiative - too many organisations with contrived acronyms have been formed, which once furnished with self-appointed committees, have become stuck in a mire of red tape and soul-searching.

...makes Jack a dull boy. Many thanks to Petra Duffield and Karen Richardson for arranging the spectacular gala dinner, to Jim Bates for his extempore saxophone accompaniment to the dance band, to Gene Spafford for his helium-induced Donald Duck impersonations, Martin Beney for providing the best photograph of the conference (regrettably not clear enough for publication), and to the Hotel de France for supplying its beautiful schooner ‘Meriliisa’, aboard which speakers and organisers assembled for some post-conference recovery.

Finally, VB looks forward to renewing acquaintances with all who attended this year’s event, at the Second International Virus Bulletin Conference in 1992.