2015-08-14

Abstract

Nearly a year after the Microsoft takedown of Vitalwerks’ dynamic DNS service No-IP, the NJRat malware campaign has re-spawned and has started making its way back to No-IP’s DDNS domains. This time, however, the malware authors are more cautious and they are finding several new ways to escape anti-virus detection. Abhishek Bhuyan and Ankit Anubhav take a close look at the Middle Eastern NJRat campaign.

Copyright © 2015 Virus Bulletin

Nearly a year after the Microsoft takedown of Vitalwerks’ dynamic DNS service No-IP [1], the NJRat malware campaign has re-spawned and has started making its way back to No-IP’s DDNS domains. This time, however, the malware authors are more cautious and they are finding several new ways to escape anti-virus detection.

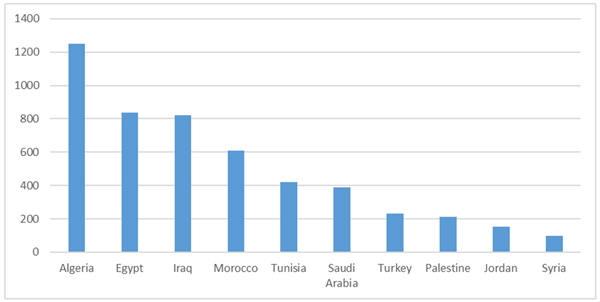

Figure 1 shows the count of unique malicious domain names found among the top 10 Middle Eastern countries. Some of the registered malware domain names were very clearly intended to spread the NJRat malware, for example:

injrathacker.no-ip.org [Morocco]

njrathost12.no-ip.org [Algeria]

njratnjrat77.no-ip.biz [Iraq]

lovenjrat123.no-ip.biz [Iraq]

njrat-tdf37.no-ip.biz [Algeria]

njrat3311r.no-ip.biz [Palestine]

mohamednjrat111.no-ip.biz [Iraq]

Figure 1. Count of unique malicious domain names found among the top 10 Middle Eastern countries (domains sorted by the geolocation of the IP address to which they point).

In Q2 2015, we observed 5,038 unique malicious domains, of which 2,228 were still actively resolving at the time of writing this article. 23 of the domains had port 1177 open, which is the default port used by the NJRat malware builder. 200 of them had port 80 open, and on scanning those ports, we found that many were pointing to home ADSL routers. This tells us that these operations are mostly being carried out on home networks and that the attackers may be hobbyist hackers. On the other hand, some hackers were using the IPjetable VPN service to retain anonymity, so it appears to be a unique mix of script kiddies and professional hackers when it comes to Middle Eastern users of NJRat.

Surprisingly, among the Windows systems tracked, Windows XP proved still to be a common choice for malware authors to run on their servers.

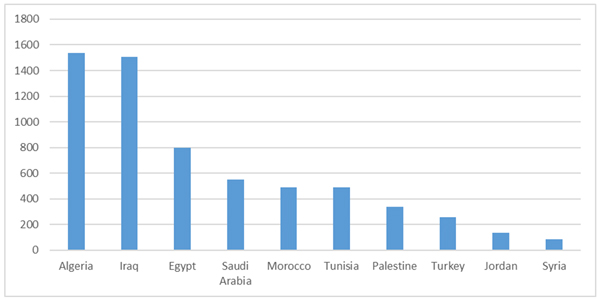

In Figure 2 we see the count of unique payload hashes associated with malicious domains in Middle Eastern countries.

Figure 2. Count of unique payload hashes associated with malicious domains (domains sorted by the geolocation of the IP address to which they point).

When we looked at the BGP prefixes that were being used by the attackers, we found that Algerie Telecom (AS36947) was the most abused. Figure 3 shows the top 10 BGP prefixes we found used by attackers, half of them belonging to AS36947.

It was noted that, in the past, malware authors based in the Middle East often made very little effort to conceal themselves from anti-malware techniques, as the project path and top-level information in the payload binary was often obvious, for example ‘Trojan.exe’.

This trend has changed, as malware authors are now trying to perform specific actions to evade AV detection. In an Arab-based forum, notorious for hosting malware and acting as a source of knowledge transfer between various malware authors, we came across a video tutorial on how to evade detection. There are several individual discussion threads on how to evade detection by different anti-virus vendors.

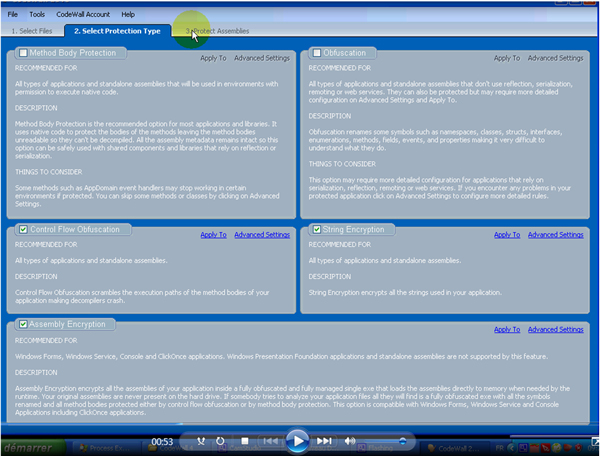

In Figure 4, a malware author shows specifically how to bypass Avira anti-malware protection by using a third-party packer/obfuscator such as CodeWall.

He goes to the trouble of making a video tutorial on how to encrypt ‘server.exe’, the default name used by the NJRat builder (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Video tutorial on how to encrypt ‘server.exe’, the default name used by the NJRat builder.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 5.)

In a separate thread, the same malware author, ‘Adroun’, who also likes to call himself ‘Mr. Morocco’, gives a detailed video demonstration of how to evade detection by Kaspersky anti-malware products (see Figure 6). The video contains instructions both in Arabic and in French. The trick advised here is simply to change the offset of the binary via a custom hacktool.

To prove his point, the malware author provides us with screenshots of the malware before and after the change. Before the offset change Kaspersky detects the malware, however it fails to do so after the offset change, or so the author claims.

Figure 7 shows the scan logs as provided by the malware author before and after the offset change.

Once the static binary is complete, it is sent to various potential victims via spear-phishing mails. When the victim has been compromised, and once a connection is established between the victim machine and the hacker, we observed an interesting sequence of packet transfer.

First, the full path of the malware executable present on the victim’s system is sent to the hacker. The encoding is simple base64:

QzpcVXNlcnNcS2xvbmVcQXBwRGF0YVxSb2FtaW5nXE1pY3Jvc29md FxXaW5kb3dzXFN0YXJ0IE1lbnVcUHJvZ3JhbXNcU3RhcnR1cFxjcm Fjay5leGU=

After base64 decoding, this is simply:

C:\Users\[*Confidential*]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\crack.exe

[*Confidential*] is a string replacing the username of the malware replication system we used in tracking this threat.

The hacker-to-victim communication consists of malicious payload transfer. In our packet monitoring system, we observed the hacker sending a doubly obfuscated wscript to the system.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 8.)

The random long variable names and function names are consistent with a VisualBasic obfuscator tool authored by hackers identifying themselves as ‘Pepsi and Maged’.

After two levels of de-obfuscation we see the plain wscript in action. Once the control is transferred to the hacker, he can download and execute a payload, update the malware, or even in some cases uninstall it to avoid getting caught.

The malware also checks whether any anti-virus product is present on the victim’s machine (Figure 10).

Finally, the server on which the data is uploaded/downloaded is revealed.

We performed a port scan on a randomly found live system. The malware author’s PC username, ‘ALI-PC’, was using Windows 7 OS.

When opened with port 11778 here, the live site log was accessible directly from the browser. In this case, we could see a cycle of three commands. The malware author tries to send two different payloads from his system, and then sleeps for 5,000 seconds. This cycle keeps repeating. We could see the change of commands when we refreshed the URL at specific intervals (Figure 12).

After de-obfuscation, we found the Skype contact of the malware author. In his ‘about me’ information he is trying to sell a piece of malware named ‘H-worm plus’.

We were curious to find out more about the propagation scheme of NJRat – for example, whether there is a fixed method or whether the malware authors rely on social engineering techniques. Posing as a novice hacker, we initiated a discussion with the malware author via Skype. In our discussion, he told us that the malware depends on social engineering techniques to spread, i.e. sending the malware file directly to the victim via Facebook or Skype. He advised us to disguise the executable as a .doc, .ppt, .xls or .pdf file (a common technique used by malware authors to make an executable look like an innocuous document by changing attributes such as its extension name and its icon). The screenshots in Figure 13show snippets of our conversation with the malware author.

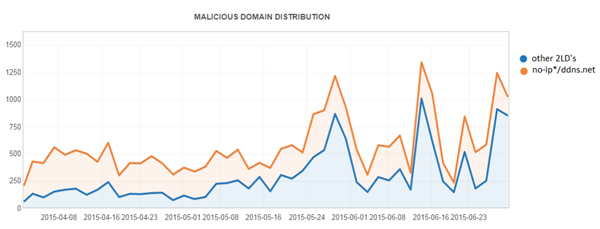

Dynamic DNS seems to be the best option for attackers for using a C&C without leaving much evidence for attribution (e.g. Whois info, registration verification). There are many providers of such services, both free and paid. There is a huge list of predefined domains under which one can register any subdomain, just like choosing a personalized name. The best part is that IPs can be changed frequently and can randomly generate subdomains to avoid blacklists. The no-ip.* and ddns.net second-level domains seem to be the most popular choice in the Middle East, since those are both free.

The histogram in Figure 14 shows the distribution of malicious domains for Q2 2015 with no-ip.*/ddns.net and other second-level domains (there are a few other dynamic DNS providers as well). We can see that the former has always dominated in terms of number of domains.

Figure 14. Distribution of malicious domains for Q2 2015 with no-ip.*/ddns.net and other second-level domains (2LDs).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 14.)

Unlike double-flux, an attacker won’t be able to do anything with a name server as these services have fixed name servers. Upon resolving, the authoritative name servers associated with no-ip.*/ddns.net are nf[1–5].no-ip.com. These name servers are also used by the other second-level domains provided by No-IP.

One could keep an eye on all the new domains coming up in one’s infrastructure that are resolved with these authorative name servers rather than tracking FQDNs one by one.

The malware authors can brute force an AV signature and can come up with ways to evade static detection by using new packers/obfuscating the static sample. However, at the end of the day the behaviour is the same, i.e. dropping a file in AppData, altering the registry to allow this dropped file to bypass the firewall, connecting to No-IP domains to upload stolen data, and executing commands via a backdoor.

One detection approach can be to base detection on the CodeWall packer itself, however this risks the AV producing false positives on legitimate samples packed by CodeWall, which is a legitimate packer intended to prevent reverse engineering of software packages.

Behavioural detection provides a safe way to detect the sample based on malicious activity regardless of the static obfuscation/packers used (which the malware authors keep changing with time).

NJRat remains a prominent cyber weapon of choice among hackers in the Middle East, used both by professional hackers and hobbyists. One reason for its popularity may be the abundance of literature and support available for the tool in Middle Eastern hacker forums (such as Dev Point). Forums like these use Arabic exclusively, hence a hacker who is based in the Middle East and not fluent in English can kick-start NJRat easily.

[1] No-IP confirms Microsoft’s takedown and discusses its status. http://www.noip.com/blog/2014/07/10/microsoft-takedown-details-updates/.