2015-06-25

Abstract

During a long-term investigation, Brian Wallace discovered two forensic artefacts - both GUIDs - which can be used to determine whether multiple malware samples are from the same Visual Studio project, effectively identifying the family, and to identify samples that are the result of the same build, allowing for the identification of post-compilation modifications made by tools such as builders. Here, he describes his discoveries and how these new artefacts can help malware hunters around the world.

Copyright © 2015 Virus Bulletin

During a long-term investigation, I uncovered forensic artefacts not commonly used in .NET assembly analysis. These artefacts are both GUIDs (globally unique identifiers). One is created by Visual Studio on the creation of new projects and stored as a string, the other is generated on every build and stored as a binary value. These GUIDs can be used to determine whether multiple samples are from the same Visual Studio project, effectively identifying the family, and to identify samples that are the result of the same build, allowing for the identification of post-compilation modifications made by tools such as builders. After releasing an open-source tool to extract these GUIDs, we suggested that VirusTotal integrate this functionality. They have done so, allowing for these new artefacts to help malware hunters around the world.

Months deep into an investigation of an Iranian operation we dubbed ‘Operation Cleaver’ [1], I found myself buried up to my eyes in malware samples to reverse engineer. As an employee of a start-up, I am no stranger to situations where the options are innovate or die, and this was one of them. Through some simple pre-processing data I gathered on the large number of samples located on a public FTP server, I could tell that a substantial percentage of the malware had been developed in a .NET-based language. Having previously worked as a software engineer developing in C#, I was quite familiar with .NET and recalled that it makes greater use of GUIDs than some other languages. I identified two GUIDs that could be of assistance in reducing the number of samples that needed to be fully reversed.

The Module Version ID, or MVID, is a GUID that can be used to distinguish various versions of a .NET module. This value is generated at build time, resulting in a new GUID for each unique build. This GUID is stored in a binary format (as opposed to string format) in a defined location in .NET assemblies. The GUID resides in the GUID heap, and its location is identified in the Module table of the MetaData tables in the .NET MetaData header.

What can we do with knowledge of this identifier? By itself, it can assist in identifying post-compilation modifications made by tools such as builders that generate customized malware binaries from a common source binary. In other cases, it can assist in identifying instances where a legitimate .NET sample has been modified.

It should be noted that the MVID can be modified by a malware operator. An informed malware operator could do this with a hex editor.

Extracting the MVID statically by parsing the PE and the .NET metadata can be somewhat difficult. This is because the format relies on a large number of variables that can lead to intricacies in parsers. There are a number of simpler ways to extract the MVID.

The disassembling counterpart to ilasm (Microsoft’s tool for converting Common Intermediate Language code to a portable executable), ildasm, is used to convert .NET assemblies back to the common intermediate language code. In addition, it extracts and displays the MVID which can be searched for specifically with the find command on Windows platforms.

> ildasm /text /all af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc5ee1c0d29e3a0dcd96e67c65a085 | find "MVID"

// MVID: {F2A0DA69-155E-4543-AD0A-206026E206DB}

As a heavy Linux user, it would be remiss of me not to include a more Linux-friendly solution as well. We can obtain similar results using monodis, ildasm’s counterpart in Mono (an open source implementation of Microsoft’s .NET framework), along with grep, the Linux equivalent to Microsoft's find.

> monodis af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc5ee1c0d29e3a0dcd96e67c65a085 | grep GUID

.module E.exe // GUID = {F2A0DA69-155E-4543-AD0A-206026E206DB}

It should come as no surprise to developers with .NET experience that there is a simple method to obtain the MVID of another .NET assembly:

var aAssemblyToAnalyze = Assembly.LoadFile(strPathToFileToAnalyse); // DO NOT DO THIS var mvid = aAssemblyToAnalyze.ManifestModule.ModuleVersionID;

This method should not be used, and the next section will explain why.

While working on a method to extract the MVID as well as the TypeLib ID from .NET samples, I became curious about the additional attack surface created by loading a .NET assembly with no intention of executing it. I found something interesting when testing with mixed .NET assemblies. Mixed assemblies, which are built with both .NET and unmanaged code, were intended to act as a stepping stone for developers migrating projects from purely unmanaged code to .NET. Mixed assemblies are still identified as .NET assemblies, but also contain a DllMain entry point, which is executed when loaded with Assembly.Load and related functions. A full description of this issue can be found in [2]. The brief explanation is that it allows for an assembly to execute code when loaded with Assembly.LoadFile and similar methods, which could be abused to gain control of a system inspecting a malicious sample.

In order to work around this issue, any assemblies loaded purely for inspection should be loaded with Assembly.ReflectionOnlyLoadFrom instead of Assembly.LoadFile, or any of the reflection-only method alternatives. While it does protect from this specific issue, there may be other unexplored attack surfaces, so it’s best, in my opinion, to treat this method as risky but more secure than the non-reflection-only method.

var aAssemblyToAnalyze = Assembly.ReflectionOnlyLoadFrom(strPathToFileToAnalyse); var mvid = aAssemblyToAnalyze.ManifestModule.ModuleVersionID;

The TypeLib ID is a GUID generated by Visual Studio on the creation of a new project by default.

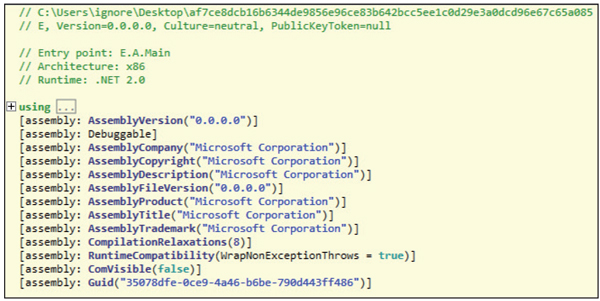

It is stored in Properties/AssemblyInfo.cs and is made visible to the developer. The developer can choose to modify this value, or remove it completely (Figure 1).

Due to its location in source code, a good number of these GUIDs can be found on public code repositories such as GitHub. In a search query [3], we can see that there are more than 800,000 results of projects/files which contain GUIDs defined for the assembly.

Since this value is created by Visual Studio on project creation, and is stored in source code, it is consistent across all builds of the .NET assembly unless it is modified by the developer. We can use the TypeLib ID to assist in identifying builds resulting from the same Visual Studio project, whether developed by a single developer or through sharing of the source code.

We also observed that this value is often ignored by obfuscation tools, so even after .NET malware has been obscured by a tool such as SmartAssembly, the TypeLib ID may still be used to identify a sample as belonging to a certain Visual Studio project.

When using the TypeLib ID to identify samples, researchers should note that it is simple for a malware operator to modify this value not only with access to the source code, but also statically. This could be done simply with a hex editor. A malware operator with the source code could even remove the TypeLib ID altogether.

Since the TypeLib ID is actually a string in the source code, it is not stored on the GUID heap like the MVID, but instead in the Blob heap. Since it is not a required field, it is not stored in a static location in the .NET metadata header either, but is instead listed in the CustomAttribute table. This adds complexity to the static extraction of this value, more so than the MVID.

Tools like ILSpy [4] and similar tools which decompile .NET assemblies for analysis can easily recover the TypeLib ID (and the MVID for that matter). No additional action is required for these tools to recover this value beyond simply opening the target assembly (Figure 2).

Figure 2. No additional action is required for tools such as ILSpy to recover the TypeLib ID value beyond simply opening the target assembly.

We can identify the value as the ‘assembly: Guid’ value.

The simplest secure programmatic method I know of for extracting the TypeLib ID is to use .NET to load the assembly (in reflection-only mode) as we did to recover the MVID. Using a reflection-only mode makes the code slightly more complicated, but the resulting code is still quite simple (and secure compared with its non-reflection-only counterparts).

var assembly = Assembly.ReflectionOnlyLoadFrom(“af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc5ee1c0d29e3a0dcd96e67c65a085”);

foreach(var r in assembly.GetCustomAttributesData())

{

if (r.AttributeType.FullName == “System.Runtime.InteropServices.GuidAttribute”)

{

Console.WriteLine(r.ConstructorArguments[0].Value);

break;

}

}

The GUID itself is stored as an ASCII string in the resulting PE. While this method is not particularly recommended for accuracy, it does demonstrate that detection of TypeLib IDs can be done in tools such as YARA as long as some expectation of false positives is accepted (useful for searching via services such as VirusTotal Hunting). The following is an example of using strings, grep, cut and head on a Linux system to obtain the TypeLib ID:

> strings af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc5ee1c0d2

9e3a0dcd96e67c65a085 | grep -iE “\\\$[a-f0-9]{8}-[a-f0-9]{4}-[a-f0-9]{4}-[a-f0-9]{4}-[a-f0-9]{12}” | head -n 1 | cut -b 2-

35078dfe-0ce9-4a46-b6be-790d443ff486

In order to make extraction of both GUIDs not only simple but also cross-platform, I developed a simple open-source tool in Python 2.7 named GetNETGUIDs. This tool is hosted on GitHub and can be downloaded from [5].

When GetNETGUIDs is run against a .NET sample, four rows are printed: the TypeLib ID, MVID, SHA256, and path to the sample.

> getnetguids.py af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc 5ee1c0d29e3a0dcd96e67c65a08535078dfe-0ce9-4a46-b6be-790d443ff486 f2a0da69-155e-4543-ad0a-206026e206db af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc5ee1c0d29e3a0dcd96 e67c65a085 /tmp/af7ce8dcb16b6344de9856e96ce83b642bcc5ee1c0d29e3a0 dcd96e67c65a085

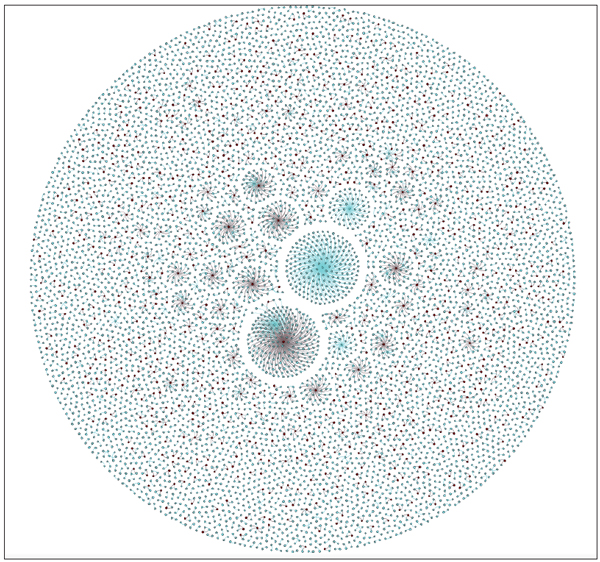

By utilizing GetNETGUIDs along with Gephi [6] and a helper Python script, we can visually cluster the DotNET malware set from VirusShare [7] (Figure 3). In the visualizations, the red nodes represent TypeLib IDs, the light blue nodes represent MVIDs, and the portable executables are greenish-blue. An edge from a portable executable to either a red or light blue node represents that the portable executable uses that GUID for that purpose. Multiple samples that are connected to the same TypeLib ID or MVID are potentially related.

Figure 3. The red nodes represent TypeLib IDs, the light blue nodes represent MVIDs, and the portable executables are greenish-blue.

Similarly, we can visually cluster samples from the Operation Cleaver campaign (Figure 4).

Shortly after releasing GetNETGUIDs, I reached out to a member of the VirusTotal staff to discuss integrating this research into VirusTotal. Since I found it useful during the Operation Cleaver investigation, I wanted to make it available to anyone who might need it to fight advanced threat actors running rampant, as well as be able to use it myself in VirusTotal. Since GetNETGUIDs is open source, the VirusTotal team were happy to integrate it. (Thanks to Julio Canto at VirusTotal for being so open and helpful!)

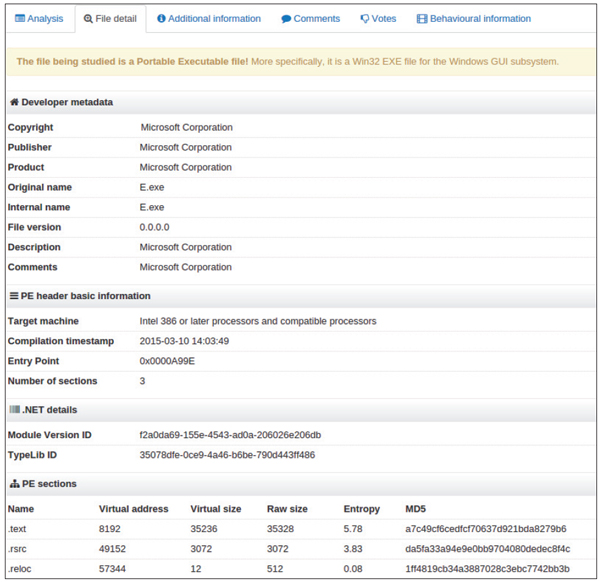

Now, when a user submits a .NET sample file to VirusTotal, the GUIDs mentioned above will be extracted and displayed in the File Detail tab, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. When a user submits a .NET sample file to VirusTotal, the GUIDs will be extracted and displayed in the File Detail tab.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 5.)

The .NET details section contains both the Module Version ID and TypeLib ID for this sample.

The VirusTotal Intelligence platform, which is available with some VirusTotal subscription packages, provides a large number of invaluable features. One of these allows users to search for samples based on a wide variety of fields. As part of the integration of GetNETGUIDs into VirusTotal, a search field was added to search for both MVIDs and TypeLib IDs. This field is the ‘netguid’ search field. We’ll first search by the MVID, as shown in Figure 6.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 6.)

We find that our original sample shows up in the results, along with another sample, which is very similar to the original one (another Black Worm sample). One could assume that at least one of these files was modified after being compiled.

Next, we will search based on the TypeLib ID, as shown in Figure 7. We can see that this query produced more samples, as expected. Since there are multiple builds of this malware, we can see all samples resulting from that Visual Studio project. There are many other samples that share the same TypeLib ID (which are also Black Worm samples), but since this is a new feature, it has not been applied across VirusTotal’s complete available sample set. This means that the feature will appreciate in value as more samples are processed.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 7.)

Next, we will search for a combination of MVID and TypeLib ID, as shown in Figure 8.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 8.)

By searching for both, we are looking for samples which have both this MVID and TypeLib ID, making it far less likely that there was a collision on either. You might notice that the results are identical to those from the MVID-only search, further confirming their accuracy.

Security researchers need to take advantage of every possible tool as they battle threat actors. We hope that researchers will find it easier to uncover and identify .NET malware using MVID and TypeLib ID as artefacts – not only with extraction methods available in examples, code and scripts, but also with help from VirusTotal.

Good hunting, fellow malware hunters.

[1] Operation Cleaver. http://cylance.com/operation-cleaver/.

[2] Wallace, B. Implications of Loading .Net Assemblies. http://blog.cylance.com/implications-of-loading-net-assemblies.

[3] GitHub search query showing more than 800,000 results of projects/files which contain GUIDs defined for the assembly. https://github.com/search?p=1&q=%22%5Bassembly%3A+Guid%28%22&type=Code&utf8=%E2%9C%93.

[4] ILSpy. http://ilspy.net/.

[5] GetNETGUIDs. https://github.com/CylanceSPEAR/GetNETGUIDs.

[6] Gephi. http://gephi.github.io/.

[7] VirusShare. http://virusshare.com/.