2015-02-10

Abstract

Brazilian bad guys have created a unique way of stealing money from people who prefer to keep their lives entirely offline. By altering ‘boletos’ - popular payment documents issued by banks and all kind of businesses in Brazil - cybercriminals have successfully stolen vast amounts of money, even from people who don’t own credit cards or use Internet banking accounts. In his VB2014 paper, Fabio Assolini explains how these attacks have happened, and gives advice on how to protect customers even when they have chosen to live their lives offline.

Copyright © 2015 Virus Bulletin

José is a very mistrustful person. He never uses Internet banking services or buys anything using a credit card. Indeed, he doesn’t even have one. He doesn’t trust any of these modern technologies in the slightest. He’s well aware of all the risks that exist online, so José prefers to keep his life offline. However, not even that could save him from today’s cybercriminals, and he lost more than $2,000 in a single day: José was p0wned by a barcode and a piece of paper.

Brazilian bad guys have created a unique way of stealing money from these cautious, offline-only types: changing ‘boletos’ [1], popular banking documents issued by banks and all kind of businesses in Brazil. Boletos are actually one of the most popular ways to pay bills and buy goods in Brazil – even government institutions use them – and they are a unique feature of the Brazilian market.

In a series of online attacks targeting flaws on network devices – especially DSL modems [2] – and involving malicious DNS servers, fake documents, browser code injections in the style of SpyEye, malicious browser extensions and a lot of creativity, the crooks have successfully stolen vast amounts of money, even from people who don’t own credit cards or use Internet banking accounts. It’s a new worry for banks and financial institutions in the country.

This paper explains how these attacks have happened in Brazil, and gives advice on protecting customers even when they have chosen to live their lives offline.

Boletos are a very popular and easy way to pay bills or buy goods in Brazil – even online stores will accept this kind of payment. All you need to do is print your boleto and pay it. According to the Brazilian Central Bank [3], 21% of all payments in the country in 2011 were made using boletos (see Figure 1).

According to e-bit [4], boletos were the preferred payment method for 18% of all e-commerce transactions in Brazil in 2012 (see Figure 2).

A boleto comes with an expiry date. Prior to that date, it can be paid at ATMs, the branches and Internet banking services of any bank, the post office, lottery agents and some supermarkets. After the expiry date, it can only be paid at a branch of the issuing bank and a fee is levied by the bank; the fee increases with every passing day beyond the expiry date. Banks also charge a handling fee for every boleto paid in by a customer. This fee varies from BRL 1 to BRL 12 (roughly $0.45 to $5.40), depending on the bank. There are two types of collection: registered (where billing information is sent to the bank beforehand) and unregistered (where bills are not pre-registered in the banking system). If the collection is registered, then the bank will also charge a fee for every boleto issued, regardless of whether or not it has been paid. Therefore, unregistered collection is more suitable for online transactions.

The bank also takes into account the size of the merchant, so a merchant with a higher volume of banking transactions, that has been working with the bank for a while, etc., is able to get lower fees or even fee exemption. This transforms the boleto into a very important sales tool within big companies, e-commerce firms and the government. If a company wants to do business in Brazil, it definitely need to use boletos – Apple [5], Dell, Skype [6], Microsoft, and even FIFA [7] in the 2014 World Cup have all used them in their local operations (see Figure 3).

Figure 4 shows the basic structure of a printed boleto bancário.

Issuer bank: This is the financial institution responsible for issuing and collection based on an agreement between itself and the merchant. The bank, once authorized to collect payment for the merchant, will credit the amount owed by the client to the merchant’s bank account.

Barcode: This is a code consisting of a group of printed and variously patterned bars (always 103mm in length and 13mm in height), spaces and sometimes numerals that is designed to be scanned and read by a digital laser scanner and which contains information to identify the object it labels.

Identification field: This is a numerical representation of the barcode – it contains all the information necessary to identify the merchant’s bank account and allow the clearance. This field is used in home and self-service banking.

To pay a boleto at a bank or online, all that is necessary is to scan the barcode – if it’s unreadable (due to a bad print), users can type in the 44-digit identification code instead. Some banks have a barcode scanner in their mobile apps, so m-banking users don’t need to type the ID field, they can simply use the phone’s built-in camera to pay the boleto (see Figure 5).

What could possibly go wrong? Well, how about changing the barcode or the ID field? It’s simple to do, and it means that payments can be redirected to a different account. That’s exactly what Brazilian fraudsters started to do – and the easiest and most effective way to do so was, of course, using malware.

A boleto can be generated and printed by the store that is selling its products to you, or even by users themselves during an online purchasing process. It is displayed in the browser using free libraries that are available for developers to implement in their ERP software or in their online store systems.

The extensive documentation and legitimate open-source software used to generate boletos have helped malware creators to develop trojans which are programmed to change boletos locally, as soon as they are generated by the computer or browser. These trojans were spotted in the wild in April 2013 [10], and are still being distributed in Brazil today.

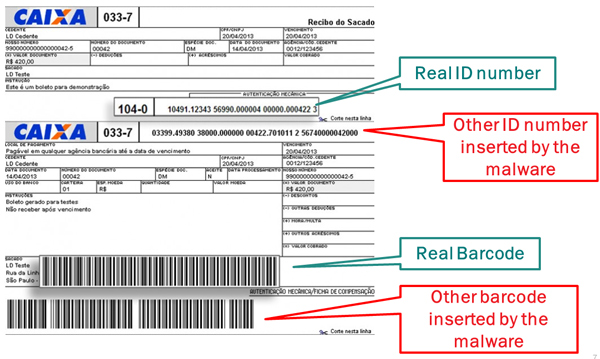

The first generations of the malware chose to change the ID field number and the barcode, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. A boleto modified by a Brazilian trojan: the new ID number and barcode redirect the payment to the fraudster’s account.

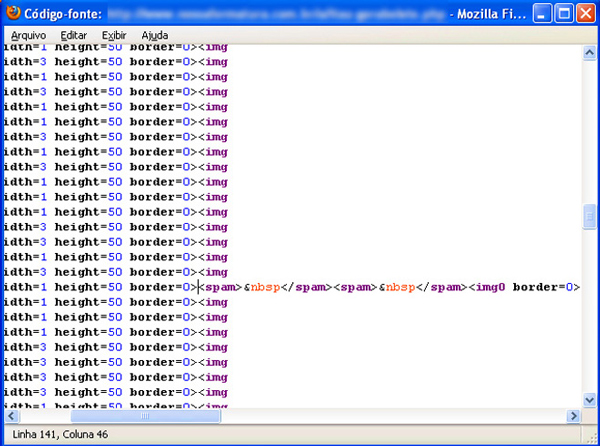

The malware uses a JavaScript injection to change the content of the boleto, as shown in Figure 8.

Later versions of the trojan started to change only the numbers in the ID field, as shown in Figure 9.

These newer versions also used a span HTML element in order to add a white space into the barcode, breaking it and making it unreadable. That forces the customer or bank staff to type in the doctored 44-digit ID field in order to pay the boleto. So as not to raise suspicion, the trojan does not change the value or due date for the transaction (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. HTML page changed by the trojan: a white space is added to invalidate the barcode. (Source LinhaDefensiva.org [11].)

The ID field includes a lot of information, including details of the bank account that will receive the payment and other data used according to the rules established by each bank (see Figure 11). The ‘Nosso Número’ data (‘Our ID Number’) is a unique identifier, which is different for each boleto. Changing the ID number is enough to redirect the payment to another bank account.

This attack is especially notorious for its ‘crossover’ to the offline world, stealing from those who do not use Internet banking or buy things online. It can even steal from people who have never connected to the Internet in their lives. It resulted in infected computers in thousands of stores all over the country generating fraudulent boletos for their customers. Once printed and paid, the boletos sent the money directly to the cybercriminals’ accounts.

This sparked an avalanche of trojans using the same technique, and several businesses were badly affected. Many companies, the association of shop keepers and the Brazilian government all issued alerts to their customers about the fraudulent boletos being issued by these trojans (e.g. [12], [13], [14], [15]). A lot of money was stolen, and even now this fraud is still costing banks, stores and customers dearly.

Since most boletos are generated in a browser, the trojan installs a BHO that is ready to communicate with a C&C server and monitor traffic, looking for words such as ‘boleto’ and ‘pagamento’ (payment), choosing the exact moment to inject the code (see Figure 12). It also replaces an ID number stored in the HTML with a new one, downloaded from the C&C server.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 12.)

Initially, most of these BHOs had a very low detection rate and were detected as a trojan banker by normal anti-malware products (e.g. the MD5s 23d418f0c23dc877df3f08f26f255bb5 [16] and f089bf60aac48e24cd019edb4360d30d [17]). An example of a request made by these BHOs, and the response with the new ID number to be injected, is shown below:

Request: http://141.105.65.5/11111.11111%2011111.111111%2011111.111111%201%201111111111 Response: 03399.62086 86000.000009 00008.601049 7 00000000000000

To measure the problem, we sinkholed some C&Cs and found several victims – in just one malicious server, the logs registered more than 612,000 requests in three days. Each one sought a fraudulent ID field to be injected into boletos generated on the infected machines (see Figure 13).

We also found very professional-looking control panels used by the fraudsters to collect data from infected machines and register the moment a boleto is generated. It’s the same infrastructure as used in the development of trojan bankers – a fraudulent boleto is just a new way to steal money from the users.

On investigating the attack vector used by the fraudsters and looking at how the victims got infected, we found that all possible techniques have been used. Social engineering attacks via well designed email campaigns are the most widespread, but the most aggressive path includes the massive use of RCE on vulnerable DSL modems: in 2011/12 more than 4 million of these devices were attacked in Brazil [18] and had their DNS settings changed by cybercriminals – the same approach is still being used to distribute this malware.

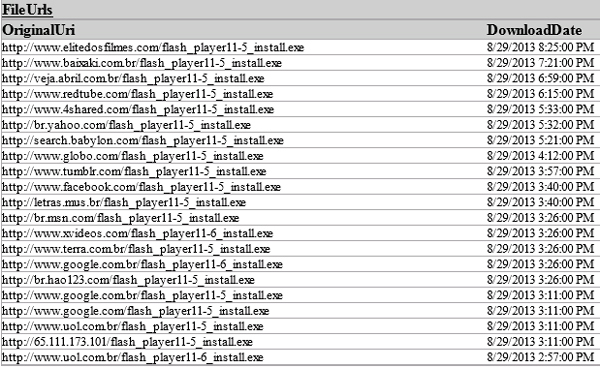

When an affected user tries to visit popular websites or Brazilian web portals, the malicious DNS configured in the DSL modem offers to install a new Flash Player. In reality, accepting this installation causes the machine to be infected (see Figure 15).

Figure 15. Is Google.com hosting a Flash Player installer? No, it’s the malicious DNS in the DSL modem.

However, the problem worsened when the bad guys decided to move more of their efforts online.

Some fraudsters decided to do more than merely spread their trojans. They wanted faster returns and shifted to a more online approach. That meant investing in sponsored links, creating fake websites that claimed to recalculate expired boletos (which is possible with this payment system), and malicious browser extensions for Google Chrome.

One attack started with a message promising 100 minutes of free credit on Skype, as shown in Figure 16.

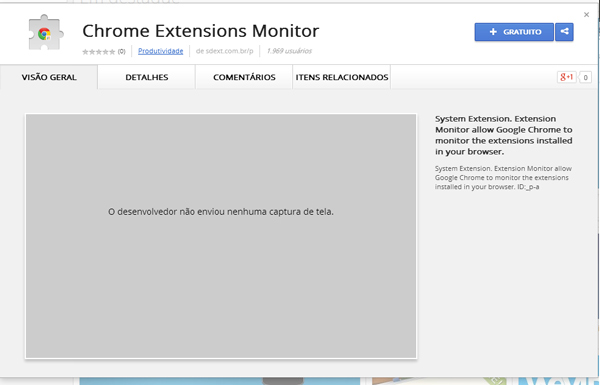

Why distribute a trojan when you can trick users into installing a malicious browser extension that controls and monitors all of the traffic? That’s exactly what the bad guys did, using the valuable help of the official Google Chrome Web Store, which hosted the malicious extension, as shown in Figure 17.

And that wasn’t the only one, we found more (Figure 18), and another, disguised as a financial app that generates boletos (fake ones, of course), as shown in Figure 19.

Figure 18. Trojan-Banker.JS.BanExt.a, found in June 2014 in the Chrome Web Store – almost 2,000 users installed it.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 19.)

The extension was prepared to do exactly the same as the BHO does in an infected machine: monitor traffic, wait for the moment a boleto is generated, then communicate with a C&C server (see Figure 20) and inject a new ID field number into the boleto, invalidating the barcode (Figure 21).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 21.)

Customers of small banks could not escape the attack –malicious extensions were set up to target a long list of local banks, as shown inFigure 22 .

The huge number of malicious extensions prompted Google’s decision [19] at the end of May 2014 to limit the installation of Chrome extensions. Now they can only be hosted on the Chrome Web Store – but as we have seen, it doesn’t seem to be a problem for cybercriminals to upload their malicious creations to the Web Store.

Another interesting characteristic of boletos is the possibility of generating a counterpart copy, in case you lose the original one. Some banks also offer a service to customers who have missed the payment deadline and need to recalculate the value of an expired boleto and reissue it, after paying a small fee. All companies working with boletos offer these services to their customers, generally online, and cybercriminals wait there to attack.

The fraudsters decided to set up malicious websites that claim to offer re-issues or recalculations of expired boletos – but of course, the new boleto is fake and redirects the payment to the bad guys’ accounts. These attacks are carried out with the help of search engines, with the attackers buying up sponsored link campaigns and putting their fraudulent sites at the top of the results.

In a search for ‘calcular boleto vencido’ (recalculate expired boleto) or ‘segunda via boleto’ (counterpart copy) on Google, the first result is a fraudulent service, as shown in Figure 23. And Google isn’t the only one – Figure 24, Figure 25 and Figure 26 show fraudulent links showing up in searches on Yahoo!, Ask.com and Bing..

As shown in Figure 27, the fake websites that supposedly offer these services have a very professional design – aiming to trick victims into believing they are legitimate sites.

All you need to do is choose the bank that issued the boleto, type in the data and ‘reissue’ it.

Of course, the boleto that is generated has the same value and due date as you indicated, but the ID field number contains new data.

These attacks are a big headache for everyone involved in buying and selling in Brazil – banks, businesses and customers alike. When a customer is hit with a fake boleto he says it’s not his fault because he has paid the bill. The store blames the bank for failing to process the payment properly. The bank insists it is only responsible for processing the boleto, not for the content of the paperwork. The buck is passed round and around…

To complete the scenario, Brazilian bad guys specialize in identity theft. They often open bank accounts in the names of innocent people who know nothing of the situation, using stolen personal data. With money mules and accounts often opened in the name of deceased people, it’s easy to see why it’s so difficult to track stolen money.

Boletos are a very local and distinctive payment method; few other countries have anything similar and most don’t even know what a boleto is. Unfortunately, security companies pay little attention to Brazil, and miss a lot of issues that only local intelligence can detect and offer expertise in. Local criminals limit their attacks strictly to Brazilian IPs, and only install their trojans on machines operating in Brazilian Portuguese.

Brazilian cybercriminals are following the same path as their counterparts in Russia and China, with a very specialized cybercrime scene where attacks on locals require special effort to understand properly. They are also sharing knowledge with cybercriminals from Eastern Europe, exporting new techniques such the one described here, clearly inspired by SpyEye, to perform code injection.

Products such as those that include the Kaspersky Lab Safe Money [20] technology can block these attacks entirely by offering the option of opening pages in a safe mode where no malicious code can inject data. This ensures that boletos can be generated securely (Figure 30).

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 30.)