2014-07-02

Abstract

In the past five years, macro malware could be considered practically extinct – thanks mostly to the security improvements introduced into Microsoft Office products. However, in recent months, a resurgence of malicious VBA macros has been observed – this time, not self-replicating viruses, but simple downloader trojan codes. Gabor Szappanos explains why VBA macro malware is not dead.

Copyright © 2014 Virus Bulletin

VBA macro malware was the dominant beast of the second half of the 1990s. This was the era of the simple WordBasic and later VBA macro viruses, the latter starting their sharp rise on the prevalence lists with the appearance of Concept, and then slowly declining after 2001, with occasional appearances lower down the prevalence charts in the years that followed. Figure 1 shows virus prevalence by type using data aggregated from Virus Bulletin’s monthly malware prevalence stats.

In the past five years, macro viruses (and more generally, macro malware) could be considered practically extinct – thanks mostly to the security improvements that were introduced over that period of time to their main target, the Microsoft Office products.

However, this does not mean that our virus lab no longer encounters malicious Word documents and Excel workbooks – on the contrary, they have appeared on our virus radar quite frequently recently, but for a different reason. The new sightings are exploited documents using one of the Office vulnerabilities to drop or download some trojans or backdoors.

In the past couple of months, we have observed the resurgence of malicious VBA macros – this time, not self-replicating viruses, but simple downloader trojan codes.

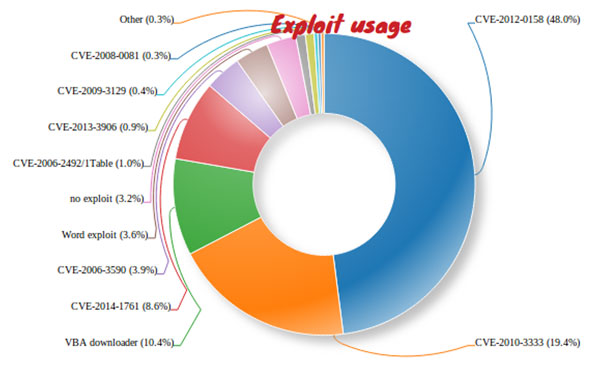

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of the document-based infection reports received by our virus lab in a two-month period, covering March and April. We can see that, following the usual suspects (the CVE-2012-0158 and CVE-2010-3333 vulnerabilities), the VBA downloaders are the next most prevalent.

Figure 2. Distribution of malicious document infection vectors. (The ‘Word exploit’ category is a medley of exploited documents where we do not identify the exact exploits – however, in the majority of cases the exploit in use is CVE-2012-0158. The ‘no exploit’ category represents the same Zeus dropper RTF embedded executables, which require the user to double-click on the embedded object, as were mentioned in our 2014 Q1 trends report [1].)

Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) is the macro programming environment of the Microsoft Office suite. Unlike the BASIC language, which is commonly perceived as a tool for beginners, VBA is quite a capable programming environment, as has been well demonstrated by macro viruses in their prime. However, the new wave of trojans described in this analysis doesn’t stretch the limits of the language, and in fact are very simplistic.

There is a complication that arises from using a VBA macro instead of an exploit to activate the infection process. In all Office suites starting from Office 2007, the execution of VBA macros is disabled by default. Consequently, the VBA code will not execute in newer versions of Office. Furthermore, the user is warned on the Word menu bar about the fact that macros have been disabled, as shown in Figure 3.

But the malware authors were prepared for this obstacle, and overcame it by deploying simple social engineering tricks. They prepared the content of the documents in such a way that it would lure the recipient into enabling the execution of macros, and thus open the door for infection.

The malware authors have been busy – since the first appearance of this group of malware at the end of January 2014, at least 75 different variants have appeared. A wide variety of document content has been used – a few examples of which are described in the following paragraphs.

The most peculiar (and one that resembles the social engineering technique used in a Napolar distribution campaign at the end of 2013 [2]) is one in which a blurred transaction report is placed in the document content, encouraging the user to enable macros in order to access the full content. Conveniently, instructions are provided as to how to enable the macros, including an arrow pointing to the exact location where the user is supposed to click (seeFigure 4 ).

A different variation of the same approach with less fancy graphical content is shown in Figure 5.

In other cases, content is marked as confidential and the user is encouraged to enable macros in order to view it, as shown in Figure 6.

Some examples are more minimalist in design, just giving out basic information, as shown in Figure 7.

A few of the samples we encountered were rather esoteric and vague, building upon the possibility that the receiver of the document will be as clueless about the point of the message as I was while reading it, and enable the macros purely through curiosity (see Figure 8).

Finally, there were cases where the malware authors left everything to the user’s imagination, giving no hints whatsoever (seeFigure 9 ).

Regardless of the document content, the result is always the same: when the user is convinced to enable macros, the malware is ready to run, and on reopening the document, the VBA code will execute.

The macro code, designed for automatic execution on opening, has the following structure (the order in which the individual functions appear and the name of the main function varies in the different variants):

Sub Auto_Open() main_code() End Sub Sub main_code() ... End Sub Sub AutoOpen() Auto_Open End Sub Sub Workbook_Open() Auto_Open End Sub

The main code is either in or called from the Auto_Open() function (which is executed when Excel is started). It is also invoked by the two other event handler functions, AutoOpen (which is invoked when a Word document is opened or Word is started) and Workbook_Open (which is invoked when an Excel workbook is opened).

Microsoft Office programs provided a couple of ways a programmer could automatically execute macros when a specific event occurred. Some of them were tied to menu commands, while the automacros were connected to global application events. If the document contained macro procedures that were using one of the predefined, special names, these procedures were called by the Office application when the specific event occurred.

In Microsoft Word, these events were tied to starting the Word application (the event could be captured with a macro procedure named AutoExec), exiting Word (AutoExit), opening a document (AutoOpen), closing a document (AutoClose), or creating a new document (AutoNew).

Microsoft Excel had a wider selection of automatic macros, but included similar functions, such as starting Excel (Auto_Open), exiting Excel (Auto_Close), opening a workbook (Workbook_Open) and closing a workbook (Workbook_Close).

The structure of the trojan’s macro code ensures that the code is executed whenever the document is opened. Even though the code itself is cross-application, and Workbook_Open and Auto_Open could make it work in Excel, we have not observed any Excel workbooks in the distribution campaigns, only Word documents. Still, the dual structure covering both Word and Excel remains in the code – probably because the malware authors were too lazy to clean up the proof-of-concept code they used as ‘inspiration’ – exactly as we observed in last year’s Napolar campaign [2].

Although all of the samples we encountered followed the simple code template described above, we could distinguish two different strains among them.

The most common strain first called the UrlDownloadToFileA Windows function to download the final payload from a hard-coded URL, then saved it either to the %TEMP% folder or the %APPDATA% folder, and finally ran it using the Shell function. The dropped executable was usually registered for automatic execution during system start-up in one of the registry autorun locations, such as HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run.

Of the 74 documents we identified as belonging to the VBA downloader campaigns (at the time of writing this paper), the vast majority (60) belonged to this group.

On looking more deeply into the Word documents, some interesting characteristics could be observed. The metadata for each document includes document creation/modification times, revision number, and the author of the document. Looking into these properties revealed that the different documents were all attributed to the same author name, ‘tps’. It is reasonable to assume that the largest number of malicious documents come from the same source.

Another useful piece of information is the name of the last user to have saved the document. This revealed some interesting names. Some just indicated the malware author’s favourite gadgets (‘DELL XPS’, ‘Xpera Z’), while others gave a hint as to the author’s name or nickname (‘Sammy Sam’, ‘Sammy2014’, ‘samy14’ and ‘samy2014’).

Even more interesting is the fact that the creation date (highlighted in Figure 11 and Figure 12) was the same for most of these documents, as shown in Figure 13.

This suggests that the development of this VBA trojan family started on 3 January, and the author didn’t bother to create a new document each time a new variant was created, but simply kept modifying the previous version by adding new social engineering content and occasionally changing the macro code – the increasing revision number also supports this assumption. Despite the fact that the last-saved-by name differs within the group, the creator is always ‘tps’ – this is another indication that this group of malware is derived from the same root document. The development of this strain appears to be an ongoing project, with the most recent version at revision number 91.

The rest of the 74 documents are likely to have been developed independently from the previous group. They use a different method, reminiscent of the VBScript downloaders from a decade ago. The remote file from the hard-coded URL is downloaded using the MSXML2.XMLHTTP object, and then the downloaded content is saved to the %APPDATA% folder or %USERPROFILE% folder, and finally executed using the Shell function.

In this strain of VBA downloaders, in each case, the author and the last-saved-by name are the same, and the creation and last-saved dates are roughly the same. This suggests a different mode of operation: rather than the same template document being modified over and over again, new ones were created most of the time.

The downloaded payloads demonstrated a wide range of ordinary crimeware. We observed:

Zeus-related AutoIt executables:

https://www.virustotal.com/en/file/ace7db9b08d65b2c4 f0c011a54571039e45ca4010aaf482c73ee7ef860019d8c/analysis/

https://www.virustotal.com/en/file/8b6757271611fe6ff0f 758bffee20e488d19b583be0352584f191d21d241bcfd/analysis/

https://www.virustotal.com/en/file/c85fe4874ddfa96845 69819db42fb321641088cbe15e6e54d28de49de26f155c/analysis/

A DotNET injector:

https://www.virustotal.com/en/file/f1b0432594bf9651ad 50d755fe1967fd2a16f112e5c0df6ebc5311166857d30c/analysis/

Old-fashioned RATs like Simda:

https://www.virustotal.com/en/file/f456df5aa1af278ccd9 958bf7f0b18ab36ed05ccb73aed8d7faec8a5898d8bcb/analysis/.

Our earlier report pointed out [1] that ordinary cybercriminals turned to Office exploits as an alternative delivery method for their creations. Current trends show that they have moved one step further into the Office realm: they have discovered the long-forgotten VBA macros and added them to their repertoire. This emphasizes the fact (I can’t even count how many times it has been proven in the past) that there is no need for fancy exploitation. When the aim is to infect a large number of users, good old social engineering never fails to deliver the results.

Finally, a piece of advice: there is no justification as to why the content of a document can only be displayed properly if the execution of macros is enabled. If you receive a document with this advice, be aware: you are probably being attacked.