2014-07-17

Abstract

Andrew Kovalev and colleagues describe ‘Mayhem’ – a new kind of malware for *nix web servers that has the functions of a traditional Windows bot, but which can act under restricted privileges in the system.

Copyright © 2014 Virus Bulletin

Over the last several years, malware writers have clearly come to understand that gaining access to web servers can bring more benefits than infecting users’ PCs. Nowadays, there are millions of completely unprotected web servers with different kinds of vulnerabilities, so it is easy for attackers to upload web shells and gain access to them. Although in the vast majority of cases such access is restricted by the web server’s rights on the target system, attackers successfully find ways to gain maximum advantage. In this article we describe ‘Mayhem’ – a new kind of malware for *nix web servers that has the functions of a traditional Windows bot, but which can act under restricted privileges in the system.

The infection of websites and even entire web servers has become common. Usually such infections are used for stealing traffic, black hat SEO, drive-by download attacks, and so on, and in the vast majority of cases this kind of malware comprises relatively simple PHP scripts. But in the last two years, several more sophisticated malware families have been discovered. Mayhem is a multi-purpose modular bot for web servers. Our team studied the bot in order to gain an understanding not only of the client part of the malware, but also some of its command and control (C&C) servers, allowing us to collect some statistics.

This article should be considered as an addition to the one published by the Malware Must Die team [1]. We faced the Mayhem bot in April 2014, and this paper is a result of our own independent research. [2] is the only other publication on Mayhem we’ve found. During our research, we also discovered that Mayhem is a continuation of a bigger ‘Fort Disco’ brute-force campaign, disclosed in [3].

Initially, the piece of malware appears as a PHP script. We analysed the version of the PHP dropper with the SHA256 hash: b3cc1aa3259cd934f56937e6371f270c23edf96d2c0801 728b0379dd07a0a035.

The results of analysing this script with the VirusTotal service are presented in Table 1.

| Date | VirusTotal results |

|---|---|

| 2014-06-17 | 3/54 |

| 2014-06-05 | 3/51 |

| 2014-06-03 | 3/52 |

| 2014-04-06 | 1/51 |

| 2014-03-18 | 1/49 |

Table 1. The results of checking the PHP dropper using the VirusTotal service.

After execution, the script kills all ‘/usr/bin/host’ processes, identifies the system architecture (x64 or x86) and system type (Linux or FreeBSD), and drops a malicious shared object named ‘libworker.so’. The script also defines a variable ‘AU’, which contains the full URL of the script being executed. The first part of the PHP script is shown in Figure 1.

After that, the PHP dropper creates a shell script named ‘1.sh’, the contents of which are depicted in Figure 2. Besides all of this, the script also creates the environment variable ‘AU’, which is the same as the one defined in the PHP script.

Then the PHP dropper executes the shell script by running the command ‘at now -f 1.sh’. This command adds a cron task. After execution, the dropper waits for at most five seconds, then deletes the corresponding cron task. If execution of the ‘at’ command fails, the dropper runs the ‘1.sh’ script directly. This part of the PHP dropper is presented in Figure 3.

The LD_PRELOAD technique allows the shared object to be the first to be loaded and allows it to hook into different functions easily. If a standard library function is re implemented in such a library, that library will intercept all calls to that function. The malicious sample contains its own implementation of the ‘exit’ function, so this one is invoked by ‘/usr/bin/host’ instead of the original one.

During execution of the hooked ‘exit’ function an additional initialization function is called. The workflow of this function is shown in Figure 4. During the initialization, the following steps are performed:

An ELF file with only an ‘exit’ function is dropped

The process forks and the child process runs the ELF file and finishes its execution

The parent process performs further initialization: it tries to connect to the Google DNS service (the IP address is 8.8.8.8), decrypts and parses the configuration file and obtains the parameters of the system.

Once initialization is complete, the shared object file is removed from the disk. The malware then tries to open and map to memory a file with a hidden file system. If the file does not exist, it is created, mapped to memory, and a hidden file system is initialized. Then this process forks, the parent process exits, and the child process continues the execution. A high-level workflow of the hooked ‘exit’ function is shown in Figure 5. The successful execution path is marked on the workflow in red. As you can see, the execution path is neither only parent nor only child. We assume that this is an anti-debugging trick for debuggers that are configured to follow only child processes or only parent processes after a fork.

After all of these steps, the child process (the only one that is alive) runs the main infinite loop of the malware. The malware sleeps for the period of time defined in its configuration and runs functions that do useful jobs.

This function first sets up a socket for communication with the C&C server, then checks whether information about the infected host has been sent to the C&C since this working session started, i.e. since the malware was executed. If the flag indicates that information has successfully been sent to the C&C server, the malware sends a ‘ping’ packet, then receives and executes C&C commands.

If the flag indicates that the information has not been sent yet, the malware prepares an HTTP packet that contains the output of the ‘uname -a’ command, the architecture of the infected system, and information about the rights of the system user executing the process. After the packet has been sent, the malware reads the C&C response and if something goes wrong it exits this function. If everything is fine, the malware updates the flag and tries to read and execute other commands in the C&C response.

A high-level workflow of the main loop function is presented in Figure 6.

During the work, the malware maintains four lists and two queues. One queue is used for input strings (strings received from the C&C server), and the other is used for output strings (strings that will be sent to the C&C server). The first list is used to store the addresses of the working functions of plug-ins, the second to store the addresses of functions that process data before writing to a socket (one used to transmit data to the C&C), the third to store the addresses of functions that process data read from a socket (data received from the C&C), and the fourth to store the addresses of functions that will process data from string queues. Figure 7 shows how these queues and lists are used in the malware’s dataflow.

Figure 8 shows the dataflow when the malware processes a task.

There are seven different commands that are used in communications between the C&C server and the malware. The commands can be divided into two groups: inbound commands (C&C to bot) and outbound commands (bot to C&C). All of these commands are sent in HTTP POST requests/responses, i.e. inbound commands are transmitted in HTTP POST requests and outbound commands are transmitted in HTTP responses to the POST requests.

By sending this command the malware tells the C&C that it has successfully been loaded and is ready to work. If the web server is run with root privileges, the format of the ‘R’ command sent to the C&C is:

R,20130826,<system architecture - 64 or 32>,<EI_OSABI value from ‘/usr/bin/host’ ELF header>, ROOT,<output of ‘uname -a command’>

If the web server is run with restricted privileges, then the command is the same, but instead of ‘ROOT’ there is the output of getenv(‘AU’) – the URL for the PHP script used to start the malware. If everything is fine, the C&C server returns ‘R,200’.

This command is sent from the C&C server to the malware. The command has the following format:

G,<task ID>

If the current task ID is not equal to the one received, the malware will finalize the currently running task and start a number of new working threads. The number of working threads is set by the ‘L’ command.

This command is used to request files from the server. If the malware wants to request a new file, it will send the following command:

F,<file name>,0

If the malware wants to check if there is a new version of a previously obtained file, it will send:

F,<file name>,<CRC32 sum of the file>

If the file is not found on the C&C server, the server will respond:

F,404,<file name>

If the file hasn’t been changed since it was received, the C&C will respond:

F,304,-

If the new/updated file is found, the server will respond

F,200,<file name>,<BASE64 encoded file data>

After receiving the command with data, the malware decodes the BASE64-encoded data, writes it to disk and into a hidden file system. Then it tries to determine whether the received file is a plug-in. If the file is a plug-in, the malware checks its CRC32 sum, which is stored in unused ELF header fields, and loads the plug-in into memory.

The ‘L’ command is used by the C&C server to configure the malware and to make it load a plug-in. If the C&C wants to configure the core module of the malware, it will send:

L,core,<number of working threads>,<sleep timeout>,<socket timeout>

After receiving this command, the malware will finalize all working threads, then update the number of working threads, the sleep timeout and the socket timeout.

If the C&C wants the malware to load a plug-in, it will send:

L,<plug-in file name>,<plug-in parameters separated by comma>

If the malware receives this command and another plug-in is already running, the running plug-in will be stopped and the new one will be looked up in the hidden file system. If the lookup fails, a file with plug-in will be requested from the C&C via the ‘F’ command. Then the plug-in will be loaded, initialized and run.

This command is used to transmit working data from the C&C to the malware and vice versa. If the C&C wants to add a string to the malware’s processing queue, it will send:

Q,string

All of these strings are added to the malware’s input queue and will be processed by a plug-in that is being run. If the malware wants to upload the results of its work, it will send:

Q,<plug-in name>, <string with results>

then remove these strings from its output queue.

This command is used by the malware to send its current state to the C&C server. The format of this command is:

P,<flag is a task is run>,<UNKNOWN>,<count of working threads>,<number of read/write requests to servers per second>,<total number of read/write operations to server since this number has been set to zero>

If the malware receives this command it will finalize all working threads, empty the input and output queue and release other system resources. After that, it is ready to process a new task.

The shared object contains configuration information stored in the data segment in an encrypted form. The decryption key is also stored in the data segment. Initially, only the first eight bytes are decrypted, then the malware checks whether the last four bytes are equal to 0xDEADBEEF. If they are, then the first four bytes represent the length of the encrypted data. After this, the rest of the ciphertext is decrypted. Figure 9 shows the pseudocode of the decryption algorithm.

We analysed the code of the algorithm and found that this is an implementation of the XTEA encryption algorithm [4], [5] with the number of rounds equal to 32; the mode of operations is ECB [6], [7].

An example of the decrypted configuration is shown in Figure 10.

All the samples we analysed had the same format for the configuration. The first part of the configura-tion contains special flags and offsets to data in the rest of the configuration array. The format of the decrypted configuration is presented in Table 2.

| Offset | Size in bytes | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | This field contains the number of eight-byte blocks in the configuration – in other words, the length of the configuration in eight-byte blocks |

| 4 | 4 | Special marker 0xDEADBEEF |

| 8 | 4 | Offset to the C&C URL |

| 12 | 4 | Sleep time between executions of the main loop function of the malware |

| 16 | 4 | Size of file mapping for the hidden file system |

| 20 | 4 | Offset to the name of the file that contains the hidden file system |

Table 2. Description of the malware configuration.

As can be seen from Table 2, a C&C address is defined directly in the malware configuration and no DGA is used.

As stated previously, the malware uses a hidden file system to store its files. The file system comprises a file that is created during the initialization. The filename of the hidden file system is defined in the configuration, but its name is usually ‘.sd0’. To work with this file system an open-source library ‘FAT 16/32 File System Library’, [8] is used. The library contains code to create and work with the FAT file system, but it is not used in the original form – some functions have been modified to support encryption. Every block is encrypted with 32 rounds of XTEA algorithm in ECB mode and the encryption key differs from block to block.

The hidden file system is used to store plug-ins and files with strings to process: lists of URLs, usernames, passwords, etc. The content of one instance of the file system is shown in Figure 11.

We developed a simple tool based on the open-source library [8] for decrypting and extracting files from such file systems. The script can be found in [9].

As mentioned before, the malware has functionality which allows it to use plug-ins. During our research we found eight different plug-ins for this bot. Plug-ins and their configuration files are stored in the hidden file system. All the plug-ins described here have been found in the wild and are used by the malware.

Every plug-in exports a structure that contains two special markers: pointers to useful plug-in functions and a string that contains the plug-in name. Every plug-in has at least two such pointers: a pointer to the plug-in initialization function and a pointer to the function that performs deinitialization. Two markers in this structure are constants: 0xDEADBEEF and a constant 20130826 that we suspect is a version of the plug-in. An example of such a structure is shown in Figure 12.

Due to the fact that all of the plug-ins are stored in the hidden file system, none of them were detected by any AV vendor when we checked on VirusTotal.

SHA256 hash sum: 9efed12a67e5835c73df5882321c4cd2dd2 3e4a571e5f99ccd7ec13176ab12cb

This plug-in is used to find websites that contain a remote file inclusion (RFI) vulnerability. During initialization, the plug in downloads a list of patterns and a list of websites to check. Then it sends special HTTP requests to the websites that try to include the ‘http://www.google.com/humans.txt’ file and analyse the corresponding HTTP responses. If the HTTP response contains the ‘we can shake’ substring, then the plug-in decides that the website has a remote file inclusion vulnerability. A part of the list with patterns is shown in Figure 13.

The results are transmitted to the C&C server with the use of ‘Q’ commands. The meanings of the commands are presented in Table 3.

SHA256 hash sum: 9707e7682dd4f2c7850fdff0b0b33a3f499e93513f025174451b503eaeadea88

This plug-in is used to enumerate users of WordPress sites. The working function of this plug-in receives a URL, transforms it, and makes HTTP requests with the following query template:

<original query without last part>/?author=<user id>

The user ID ranges from 0 to 5. If the corresponding HTTP response contains the substring ‘Location:’ and the destination URL contains the substring ‘/author/’ then the username is extracted from the destination URL. The first user to be found is transmitted to the C&C with the use of ‘Q’ commands. The meanings of the commands are presented in Table 4.

SHA256 hash sum: 84725fb3f68bde780a6349d0419bec39b03c85591e4337c6a02dcaa87b2e4ea3

The working function of this plug-in receives the hostname, makes an HTTP GET request to this host with the ‘/wp-login.PHP’ query, and searches for the substring ‘name=\"log\"’ in the corresponding query. So this plug-in identifies user login pages in sites based on the WordPress CMS. The results are sent to the C&C with the use of ‘Q’ commands. The meanings of the commands are presented in Table 5.

SHA256 hash sum: 6f96d63ab5288a38e8893043feee668eb6cee7fd7af8ecfed16314fdba4d32a6

This plug-in is used to brute force passwords for sites based on the WordPress and Joomla CMSs. The plug-in doesn’t support HTTPS. During our research, we found a dictionary containing passwords used by the plug-in. The dictionary contains 17,911 passwords. The lengths of the passwords range from 1 to 32 symbols.

SHA256 hash sum: 992c36b2fcc59117cf7285fa39a89386c62a56fe4f0a192a05a379e7a6dcdea6

This plug-in is also used to brute force passwords for sites, but unlike bruteforce.so, this plug-in supports HTTPS, and regular expressions, and can be configured to brute force almost any login page. An example of such a configuration is presented in Figure 14.

We analysed other configuration files for this plug-in and found that it was also used to brute force credentials for DirectAdmin control panels.

SHA256 hash sum: 38ee32e644cb8421a89cbcba9c844a5b482b4524d51f5c10dcb582c3c4ed8101

This plug-in is used to brute force FTP accounts.

SHA256 hash sum: d9d3d93c190e52cc0860f389f9554a86c8c67d56d2f4283356ca7cf5cda178a0

This plug-in is used to crawl web pages and extract useful information. A list of websites to crawl, as well as depth level and other parameters, are obtained from the C&C server. The plug-in also supports HTTPS protocol and uses the SLRE [10] library to work with regular expressions. The plug-in is very flexible. One of the configuration files for this plug-in is presented in Figure 15. As you can see, in this case the plug-in was used to find and collect pharmacy-related web pages.

During our research we found that three C&C servers were used to manage the botnet. We were able to gain access to two of them and to collect some statistics. A general overview of the C&C administration panel is presented in Figure 16. The interface that allows the user to add tasks to bots is shown in Figure 17.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 16.)

These two C&C servers managed about 1,400 bots between them. The first botnet contained about 1,100 bots, the second about 300 bots. At the time of the analysis, bots from both botnets were used to brute force WordPress passwords. A picture of the brute force task is presented in Figure 18 and some results of this brute force task are presented in Figure 19.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 18.)

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 19.)

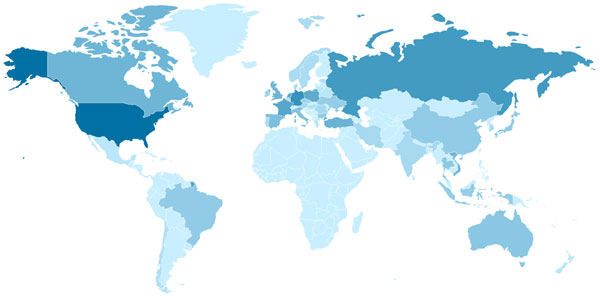

The geographical distribution of the infected servers of the botnets is presented in Figure 20. As can be seen, the countries with the highest rates of infection are USA, Russia, Germany and Canada.

Figure 20. Geographic distribution of infected servers in the larger botnet. Darker blue means more infected servers.

The third C&C server had also been identified by the Malware Must Die team [1], and at the time of our analysis it was switched off.

We analysed the sources of both active C&C servers. Besides the main page, the sources also contain two additional PHP scripts: config.php and update.php.

The first script contains configuration data: database credentials, MD5 hash of the administrative panel, maximum pending time for tasks, bot wake up time, etc. Part of this script is shown in Figure 21.

(Click here to view a larger version of Figure 21)

The update.php script is used for waking up bots. This script visits a host with inactive bots and runs the PHP script described in the ‘Malware representation’ section.

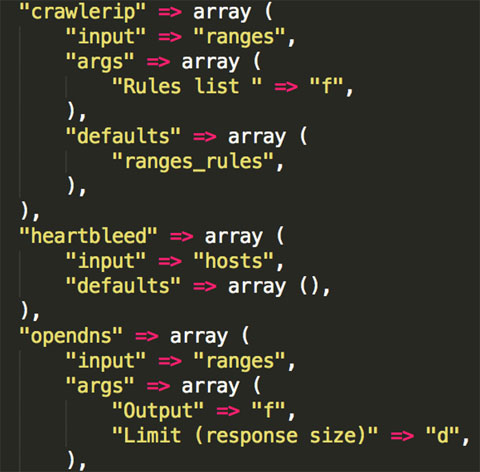

We also found that the C&C server supports a number of plug-ins that we haven’t found in the wild. For example, a plug-in that exploits the recently identified ‘Heartbleed’ vulnerability and collects data from vulnerable servers. A piece of code that describes all the available plug-ins is shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22. This piece of code shows that there are a number of plug-ins we haven’t seen in the wild.

The C&C uses MySQL and memcached (if it is available) as data storage, but plug-ins are stored on disk.

We also found that the code of the C&C scripts contains a number of security flaws, but a description of these vulnerabilities is beyond the scope of this article.

During our analysis, we found some common features shared between Mayhem and some other *nix malware. The malware is similar to ‘Trololo_mod’ and ‘Effusion’ [11] – two injectors for Apache and Nginx servers respectively. All three malware families have the following similarities:

configuration has the same format

XTEA algorithm in ECB mode is used for encryption

0xDEADBEEF markers are widely used in configuration files and other parts of code

ELF headers of shared objects are corrupted in the same way.

Despite a lack of evidence, we suspect that all these malware families were developed by the same gang.

Having completed this research, we can confidently say that botnets made up of *nix web servers are becoming more and more popular, as a modern trend in malware. Why is this the case? We think the following are some of the reasons:

Web server botnets offer a unique model of monetization through traffic redirection, drive-by download attacks, black hat SEO, etc.

Web servers have good uptime, network channels and are more powerful than ordinary personal computers.

In the *nix world, autoupdate technologies aren’t widely used, especially in comparison with desktops and smartphones. The vast majority of webmasters and system administrators have to update their software manually and test that their infrastructure works correctly. For ordinary websites, serious maintenance is quite expensive and often webmasters don’t have an opportunity to do it. This means it is easy for hackers to find vulnerable web servers and to use such servers in their botnets.

In the *nix world, the use of anti-virus technologies isn’t widespread. A lot of vendors don’t offer any proactive defence or process memory checking modules. In addition, an ordinary webmaster usually doesn’t want to spend time reading the manuals of such software and solving possible performance issues that might occur.

Mayhem is a very interesting and sophisticated piece of malware that has a flexible and complicated architecture. We hope that our research will help the security community in the struggle against such threats.

We would like to thank Fraser Howard and Charles McCathie Nevile, whose comments and suggestions helped us to improve this article.

[3] Fort Disco Bruteforce Campaign. http://www.arbornetworks.com/asert/2013/08/fort-disco-bruteforce-campaign/.

[4] Wheeler, D.; Needham, R. Correction to XTEA. http://www.movable-type.co.uk/scripts/xxtea.pdf.

[6] Wikipedia. Block cipher mode of operation. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.PHP?title=Block_cipher_mode_of_operation&oldid=582012907.

[11] Effusion – a new sophisticated injector for Nginx web servers. https://www.virusbtn.com/virusbulletin/archive/2014/01/vb201401-Effusion.