2011-01-01

Abstract

As in normal business, one of most effective ways for a banker trojan to gain market share is to do things better than its competitors, and if possible, make the migration from competitors to its own business as easy as possible. Carberp does both of these things very successfully. Toni Koivunen has all the details of this rising star in the banker trojan scene.

Copyright © 2011 Virus Bulletin

Carberp, a rising star in the banker trojan scene, first appeared in early 2010. Until recently, the Zeus trojan has been pretty dominant in the banker scene, but lately a few new contestants have entered the arena, SpyEye and Carberp being the most notable. As in normal business, one of the most effective ways to gain market share is to do things better than your competitors, and if possible, make the migration from competitors to your own business as easy as possible. Carberp does both of these things very successfully.

The data in this analysis was reversed from a Carberp variant with SHA-1: ba110352e6a5fb291973d4ea2f3ef3a0231f8afe. After a few days of tinkering I had a sufficiently reversed IDB in my hands (with 260 out of 350 functions named and prototyped).

Even though the main functionality of Carberp revolves around stealing bank credentials it is capable of a lot more tricks than that, mainly thanks to its modularity. Carberp is almost completely memory resident, requiring only a single file on the hard drive, and it can survive without administrative rights. The icing on the cake is that it has its own ‘anti-virus’ module that is designed to nuke any competition.

One of the most striking features when taking a look at the fresh IDB after unpacking is the complete lack of imported functions. The way Carberp does its deeds is that wrappers are created for all the WINAPI calls (stdlib functions such as strcmp and so on are compiled statically).

Figure 1 shows a screenshot for the wrapper around the socket() call.

The dwDllIndex refers to an array inside the ResolveFunctionFromHash() function that contains all the DLL names used by Carberp. The same hashing scheme as is used on the WINAPI names is also used on some other strings including a few process names that the malware is specifically trying to find. The hashing scheme is shown below:

DWORD HashString(char *pszApiName)

{

DWORD retval = 0;

char byte;

char *copy = pszApiName;

if(pszApiName == NULL)

{

return -1;

}

byte = pszApiName[0];

while(byte != NULL)

{

retval = (retval << 7) | (retval >> 0x19);

unsigned char key = copy[0];

retval = key ^ retval;

copy++;

byte = copy[0];

}

return retval;

}After locating the hash function it was pretty trivial to port it into a tool that hashes all the exports from all the used DLLs into a single text file. That file was then used along with the IDB to map all the wrapper functions.

One interesting feature that was spotted when running the Carberp sample in a sandbox was that it created a lot of temporary files. Closer inspection revealed that this is part of a functionality that is designed to defeat possible user-mode hooks. At several points, including the point at which the sample starts up, Carberp performs a number of checks, pushing several WINAPI name hashes and DLL names to a function.

The called function locates the specified DLL and copies it to a filename that it builds by using GetTempPathW and GetTempFileNameW. Then, using CreateFileMappingW and MapViewOfFile, the DLL in question is mapped into memory and the function starts to parse the Export directory and hash the WINAPI names, looking for the given hashes. When the correct hash is found, the function will compare the first 0x0A bytes of the function, both from the freshly mapped file and the DLL that has already been loaded into memory by the PE loader. If the bytes are different, it will copy the 0x0A bytes from the mapped DLL to the ‘real’ function offset, thus eliminating possible user-mode hooks in the process – extremely efficient, at least in theory. Carberp doesn’t even bother to set any flags to indicate that hooks have been detected. While this is a beautiful design, its implementation gets an ‘F’ for fail.

There is a tiny mistake in the code. For instance, when Carberp is checking ZwSetContextThread for possible hooks, the actual bytes being checked belong to the ZwRollforwardTransactionManager WINAPI call. I guess someone missed the fact that the number of exported names can differ from the number of exported ordinals. This renders the anti-hooking functionality pretty much useless, at least for the time being.

One interesting thing is that in a few places, early in the main function, Carberp calls the GetProcessIdForNameHash function (see Figure 2, “Carberp calls GetProcessIdForNameHash.”).

The GetProcessIdForNameHash function calls the ZwQuerySystemInformation function, passing SystemProcessesAndThreadsInformation as a parameter. In return, it receives a list of running processes and threads in a SYSTEM_PROCESSES struct. It then iterates through the list of processes, checking all process names against the provided parameter (1566CB2Ch). If a match is found, it will call the WinStationTerminateProcess function to terminate the process. Funnily enough, WinStationTerminateProcess requires Terminal Services to be enabled in order for it to work. As to the specific process that is being targeted with this, I don’t know. It was not running on my computer so I didn’t see what the hash would match. I did try brute forcing it for a while, making around 22M attempts per second on a dual-core but I didn’t get any hits, so the target for termination remains a mystery for now.

Carberp uses five executable modules, two of which are embedded in the binary itself and three that are downloaded from the C&C server. All of the modules are encrypted with the same algorithm (the webinjects are encrypted with it as well). The three modules that are downloaded are:

miniav.plug

stopav.plug

passw.plug

Miniav.plug is a DLL file, apparently created by the author of Carberp, that is a form of AV engine designed to wipe out competition such as Zeus from the infected machine. The author of the module was apparently feeling generous and left the debug information in the module. I believe the main function of the miniav.plug file says all that is needed (see Figure 3).

Stopav.plug is another DLL file. This one is designed to disable existing AV products on the infected machine. It works by creating a process belonging to the targeted AV and then injects a small thread into that process. The injected thread is responsible for removing the file(s) belonging to the AV product, after which it will kill the process itself. I suspect that the reasoning behind this is that if the file removal command comes from within the AV product’s own process, there is less chance that the AV engine will object.

The third downloaded component is passw.plug. Like miniav.plug and stopav.plug, this module is written in Delphi. The purpose of the module is to run and grab as much data worth stealing as possible. The list of software that is targeted includes:

Camfrog

Cached passwords (WNetEnumCachedPasswords)

AOL Instant Messenger

Google Talk

Windows Live

PalTalk

AIMPro

QIP.Online

JAJC from Abstract Software

Internet Explorer 7

WebSitePublisher from Crye

ICQ

MSN Messenger

Yahoo! Messenger

Gadu-gadu

Jabber

Miranda

&RQ

Mozilla Firefox

RIT The Bat!

All the data gathered by passw.plug is passed back to the main binary, which sends the data directly to the C&C server without storing it even temporarily to the disk. The passw.plug module appears to be a variant of LdPinch.

One of the executable modules that resides within the body of the main binary itself is used to take screen captures. The screen captures are also sent directly to the C&C without storing them on disk.

None of the five modules that Carberp uses ends up on the disk surface. They are decrypted on the fly and then mapped into memory, thus reducing the telltale signs of disk activity.

As mentioned, Carberp uses the same encryption scheme on all the modules it uses as well as the webinjects. The following is the decryption scheme reversed from the binary (with a few lines of additional code for clarification):

unsigned char *pData = (unsigned char *) malloc(dwFileLength);

fread(pData, 1, dwFileLength, hFile);

fclose(hFile);

unsigned long dwLength = 0;

if(memcmp(pData,”BJB”,3) == 0)

{

unsigned long dwKeyLength = pData[3];

printf(“KeyLength is %d.\r\n”,dwKeyLength);

unsigned char *pKey = (unsigned char *) malloc(dwKeyLength + 1);

memset(pKey, 0, dwKeyLength + 1);

memcpy(pKey,(const void *)&pData[7],;

dwKeyLength);

pData = pData + 7 + dwKeyLength;

dwLength = dwFileLength - 7 - dwKeyLength;

unsigned long i, j;

for(i = 0; i < dwLength; i++)

{

for(j = 0; j <= dwKeyLength; j++)

{

if(pKey[j] == 0){

break;

}

pData[i] = pData[i] ^ (pKey[j] + (i * j));

}

}

}

else

{

printf(“This does not appear to be a Carberp .plug file, aborting.\r\n”);

return 0;

}So basically the XOR key is carried in the file itself. The first DWORD after the ‘BJB’ header specifies the length of the key, and the encryption portion starts directly after the key. All the observed keys have been between six and eight characters long, with the character set containing only digits, 0–9.

Although Carberp doesn’t like being hooked, it sure does like to hook others. It copies the required number of bytes from the API to a new location, writes a jmp hook (0xE9) to the original API with the jmp offset pointing to the hook, and writes another jmp to the end of the ‘stolen’ bytes where the jump will return to the original API.

The following is the list of hooked functions:

nspr4.dll!PR_Connect

nspr4.dll!PR_Write

nspr4.dll!PR_Read

nspr4.dll!PR_Close

ssl3.dll!SSL_ImportFD

wininet.dll!HttpSendRequestA

wininet.dll!HttpSendRequestW

wininet.dll!HttpSendRequestExA

wininet.dll!HttpSendRequestExW

wininet.dll!InternetReadFile

wininet.dll!InternetReadFileExA

wininet.dll!InternetReadFileExW

wininet.dll!InternetQueryDataAvailable

wininet.dll!InternetCloseHandle

ntdll.dll!ZwResumeThread

ntdll.dll!ZwQueryDirectoryFile

ntdll.dll!ZwDeviceIoControlFile

ntdll.dll!ZwClose

Most of the hooks are for stealing data, with a few that are used to hide the malware’s presence (ZwQueryDirectoryFile for instance). One thing that seemed odd at first was the presence of the ZwDeviceIoControlFile hook. On further examination it turned out that the hook exists solely to steal FTP credentials. At the beginning of the hook a check is made as to whether the IoControlCode matches what is used when a program makes a send() call (Figure 4).

If the IoControlCode matches, the socket handle and input buffer are passed onto another function (ExamineSocketCall in the example above). Further checks are performed to check that the remote address is a loopback address and that the port is not 21. If all the checks are passed, the hook will rip out the USER and PASS fields from the stream and upload them directly to the C&C server, to a script called sni.html.

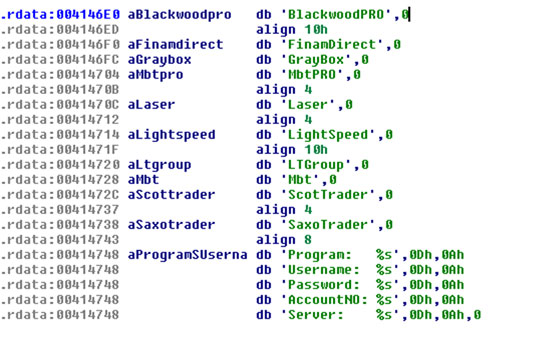

Based on certain strings in the code (see Figure 5), it seems that Carberp might be arming up to capture credentials related to various programs that are used in stock market trading.

Figure 5. Strings in the code suggest Carberp might be targeting programs relating to stock trading.

This is a bit worrying. The potential for financial damage (or, for the attackers, financial gain) is pretty high. Credentials and access to the systems that are listed in the code would enable the attackers to gain insider information as well as to perform fraudulent sales and/or purchases on stock markets. Luckily, this has not yet been implemented, but as Carberp is pretty new to the scene we may see it happening soon.

Even though Carberp is relatively new, its authors have demonstrated quite a deep technical expertise and the ability to innovate. Unless they mess up significantly, they are well on the road to snatching some market share from Zeus and the rest of the gang and it is likely that Carberp will slowly but surely gain in popularity.