2010-06-01

Abstract

Sender authentication is a hot topic in the world of email. It has a number of uses and a number of suggested uses. Which ones work in real life? Which ones don’t quite measure up? Can we use authentication to mitigate spoofing? Can we use it to guarantee authenticity? And how do we authenticate email, anyway? Terry Zink provides the answers to these questions and more.

Copyright © 2010 Virus Bulletin

Sender authentication is a hot topic in the world of email. It has a number of uses and a number of suggested uses. Which ones work in real life? Which ones don’t quite measure up? Can we use authentication to mitigate spoofing? Can we use it to guarantee authenticity? And how do we authenticate email, anyway?

The email system is modelled on the real-life postal mail system – which has both strengths and weaknesses. Let’s suppose for the sake of argument that I have a best friend whose name is Tony. Let’s also suppose that I live in the Seattle area in Washington in the US, and that Tony has recently moved to Sacramento, California. The only way we can communicate is via postal mail (neither of us knows how to use the Internet, we both refuse to pay for telephone services and we don’t know how to use smoke signals). One day, I receive what appears to be a handwritten letter. I don’t recognize the handwriting as Tony’s because I never paid attention to his writing, but the envelope is addressed to me and the return address in the top left corner shows Tony’s name and an address in Sacramento, California. If I had no other information to go on, I would assume that this letter really was from Tony.

On opening the envelope, however, I find that it is not a personal letter at all but an advertisement for a diploma from an online university. They’re offering a good deal – only $99 for a degree – but I am annoyed because someone has falsely sent me a letter in my friend’s name.

What would be useful would be if some authority traced the letter from Tony’s home in California to my place in Washington. What if the Post Office placed a ‘verified’ stamp against the return address in the top-left side of the envelope?

In other words, what if the Post Office guaranteed that the message came from where it claimed to come from by going to Tony’s place directly, verifying that the return address was correct, and then indicating with a stamp of authenticity that this was the originating address of the letter? If that were the case, then all I would have to do would be to look for that US Post Office stamp to be sure of who my mail was from.

Email, in its simplest form, is like postal mail. Anyone can send mail to anyone else, and can send mail as anyone else. My somewhat good friend Frank can send me an email, pretending to be Tony, and the email will reach me. I will initially think that the email is from Tony, but in reality it is not.

I remember back in my university days when we learned how to send ‘fake’ email. The basic idea behind this was that we could send email to whomever we wanted and specify any return address we wanted, even from a domain that didn’t exist. So, I sent a few fake messages to family and friends of mine. Oh, what great fun I had! It didn’t occur to me that ethically challenged people would exploit this for nefarious purposes.

Unfortunately, the type of postal authority I described above, which guarantees the authenticity of the originating point of a letter, doesn’t exist in real life. Fortunately, in email we can do better.

To begin with, we need to understand how email gets from point A to point B. Email travels through connections called ports. To keep track of all the different connections, the ports are numbered. Port 25 is the one that is used to transmit and receive email. When a computer attempts to transmit email, it opens a connection to port 25 and attempts to transmit using the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, or SMTP.

This whole transaction depends on five commands which constitute the core of SMTP: HELO, MAIL FROM, RCPT TO, DATA and QUIT.

HELO identifies the sending machine. ‘HELO mail.tzink.com’ should be read as ‘Hello, I’m mail.tzink.com’. However, the sender does not necessarily have to tell the truth; in fact, nothing prevents the sender from saying ‘Hello, I’m bonjour.hola.guten-tag’ or ‘Hello, I’m woozle.wozzle.gov’, or even ‘Hello, i.am.not.configured.properly’.

MAIL FROM is the command that initiates the mail processing. It means ‘I have mail to deliver from so-and-so’. The address that is specified becomes the Envelope From or Envelope Sender (or the P1 From) and it does not need to be the same as the sender’s own address.

RCPT TO is the flip-side of MAIL FROM; it specifies the intended recipient of the message. One piece of mail can be sent to multiple recipients by including multiple RCPT TO commands. The specified address becomes the Envelope To, which is also referred to as the Envelope Recipient (or P1 To). It is this that determines who the mail will be delivered to, regardless of what is in the To: line.

DATA starts the actual mail entry. Everything entered after a DATA command is considered to be part of the message and there are no restrictions on its form. Lines at the beginning of the message (before the first blank line) that start with a single word and a colon are considered to be headers by most mail programs. A line consisting only of a period terminates the message.

QUIT terminates the connection.

Below is an example mail conversation between the sending domain tony.net (Tony runs his own mail server) and the recipient domain tzink-is-awesome.com (I run one, too). The commands in bold are the transmitting machine while the ones in plain text are the recipient machine. (My examples are simplified and the actual SMTP transaction would be more complicated in real life. The email addresses are fictional, although the domains might be real.)

HELO mail.tony.net 250 mailhost.tzink-is-awesome.com Hello mail.tony.net, pleased to meet you MAIL FROM: [email protected] 250 [email protected]... Sender ok RCPT TO: [email protected] 250 [email protected]... Recipient ok DATA 354 Enter mail, end with “.” on a line by itself From: Tony Diamond <[email protected]> To: Terry Zink <[email protected]> Date: Tue, Apr 7 2010 14:36:14 PST Subject: How’s it going? So this is pretty cool, I’m sending an email message. -- Tony . 250 FAA214578 Message accepted for delivery QUIT 221 mailhost.tzink-is-awesome.com closing connection

Note the five important commands: HELO, MAIL FROM, RCPT TO, DATA and QUIT. These are the basics of what it takes to send an email. Sending email is very simple and that is its strength; Tony can log on and, using his mail server, send me an email.

Tony can send the email shown above. But so can Frank. In SMTP, there’s nothing to say that the MAIL FROM has to be Tony or Frank. Both Tony and Frank can put whatever they want into the MAIL FROM and send it to me, and I’ll get the message. And as it turns out, email’s simplicity is also its weakness.

While the postal mail service doesn’t indicate exactly where a letter was picked up from, email does (in a way) have that feature. When the receiving mail transfer agent (MTA) receives the message, it inserts additional headers which allow us to trace the message to its source. For the example above, these would be the headers from the message when the receiver got them:

From [email protected] Received: from mail.tony.net (mail.diamond-mail.net [292.13.130.22]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0) for [email protected] with EMSTP id 123456789 From: Tony Diamond <[email protected]> To: Terry Zink <[email protected]> Date: Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:36:14 PST Subject: How’s it going?

Let’s step through these one by one. The first line is the From address, which is the Envelope Sender. The Envelope Sender is generated by the receiving machine from the MAIL FROM command which comes from the transmitting machine. Note the lack of a colon in the From header – this distinguishes it from the other From: header later on. The convention is not universal, but it is common. The envelope headers are generated by the receiving machine, while the message headers are created by the transmitting machine.

The next line is a Received header. This is also an envelope header because it is generated (stamped) by the receiving machine. This Received header is important because it is the email equivalent of the US Post Office putting its stamp of authority against the originating address. If you want to see where an email came from, look for a Received header:

Received: from mail.tony.net

This piece of mail was received from a machine that calls itself (HELOs as) mail.tony.net. Next comes:

(mail.diamond-mail.net [292.13.130.22])

The IP address of the sending machine is 292.13.130.22 – Received headers will always log the sending IP address. The name of the sending machine is mail.diamond-mail.net. This name is found by performing a reverse DNS lookup of the IP address. In other words, here’s what happened:

The message was received from a machine that said its name was mail.tony.net.

The IP address of the transmitting machine was 292.13.130.22.

A reverse DNS lookup of that IP address shows its name to be mail.diamond-mail.net.

Not all IP addresses have reverse DNS lookups, but when they exist it is easier to implement a weak form of sender authentication. If it didn’t exist, the name part would be blank.

The next part of the header is the following:

by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0)

This indicates that the machine that received the message is mail.tzink.net using the (fictional) mail-receiving software MyMailer (version 1.0). This is followed by:

for <[email protected]>

This indicates that the message was addressed to [email protected]. This is the Envelope To, the address that is specified in RCPT TO by the sending machine. It is this address that the message is routed to. Note that this address does not have to be the same as the one in the To: header later on. The Envelope Sender is not always in a Received header, sometimes it is in a header elsewhere in the message. Finally, the Received header ends with:

with EMSTP id 123456789

The receiving machine assigned the ID number 123456789 to the message. This is used by mail administrators for checking logs.

The next few headers are message headers:

From: Tony Diamond <[email protected]> To: Terry Zink <[email protected]> Date: Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:36:14 PST Subject: How’s it going

These are created by the transmitting machine (Tony’s). Note that there are four important routing headers: the Envelope To, the Envelope From, the message To: and the message From:. The envelope headers are generated by the receiving machine based on the SMTP commands used by the transmitting machine, while the To: and From: headers are extra headers inserted into the body of the message (which often show up in email clients such as Thunderbird, Apple Mail or Outlook). The message is routed based on the envelope headers, not the message headers. Also note the absence of a colon in the envelope headers.

Envelope headers appear differently in different mail servers. Sometimes the envelope sender is specified in the Return-Path header.

It is important to note that my example above is simple. Often, a message will go through more routing and will have a few more Received headers. However, the Received headers outlined here are key to determining where a message came from – from Tony legitimately, or from Frank.

The system described above works well if everyone plays by the rules. But not everyone does; in fact, spammers quite often ‘cheat’ and do all sorts of malicious things to try to get their messages into users’ inboxes. From the example earlier:

Received: from mail.tony.net (mail.diamond-mail.net [292.13.130.22]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0) for [email protected] with EMSTP id 123456789

In this example, the IP (292.13.130.22) that sent the message has a reverse DNS of mail.diamond-mail.net. However, what would happen if a spammer decided to forge the HELO? What if they said ‘Hello, my name is mail.fake.net’?

Received: from mail.fake.net (mail.diamond-mail.net [292.13.130.22]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0) for [email protected] with EMSTP id 123456789

In this example, the machine claimed to be mail.fake.net, but was sending from mail.diamond-mail.net. Straight away, we can see that there is a mismatch. When we look up the IP address mail.fake.net, it turns out that it resolves to 264.33.78.90. In other words, it is completely different from mail.diamond-mail.net. Thus, we have uncovered an example of a transmitting machine claiming to be sending from one mail host, but in fact sending from another.

A smarter spammer will use a trick to bypass this. Rather than sending from an IP address that has a reverse DNS lookup (i.e. converting an IP to a domain name), they will send mail from an IP that has no reverse DNS. In that case, the received line would look like the this:

Received: from mail.fake.net (unknown [282.31.32.33]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0) for [email protected] with EMSTP id 123456789

I’ve inserted the ‘unknown’ because the above IP address does not resolve in DNS. Since the transmitting IP has no reverse DNS there’s no way to verify whether 282.31.32.33 resolves to it. Performing a DNS lookup on mail.fake.net reveals an address that doesn’t match the IP address; this is suspicious but not definitive.

A smarter spammer still would obfuscate even more:

Received: from hofgado (unknown [272.31.32.33]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0) for [email protected] with EMSTP id 123456789

The transmitting machine called itself ‘hofgado’ and sent from an IP with no reverse DNS. There’s definitely no way to resolve this because the HELO won’t resolve via a DNS lookup (‘hofgado’ is not in the proper format) and there is no reverse DNS for the IP 272.31.32.33. Nothing can be verified and we can make no assertions as to the authenticity of the message. While this certainly looks suspicious, one of the great problems of filtering spam is that misconfiguration of legitimate mail servers is incredibly common, and so looking for mail with misconfiguration as one of its features is not enough to flag a message as spam.

Each time mail goes through a relay, the receiving MTA stamps a Received header telling you where it came from and where it’s going. The analogy in the postal world would be the post office writing down on the envelope that Tony’s letter to me was picked up in Sacramento, processed in San Francisco, relayed through Boise, Idaho and then delivered to me in Seattle.

Suppose that Tony’s mail to me went through multiple hops. We can see whenever that occurs:

From [email protected] Received: from mail.jason.net (jd.net [284.33.167.99]); Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:35:35 PST Received: from bergie.net (mail.rypod.com [267.99.33.167]); Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:34:01 PST Received: from mail.tony.net (mail.diamond-mail.net [292.13.130.22]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0); Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:33:15 PST From: Tony Diamond <[email protected]> To: Terry Zink <[email protected]> Date: Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:36:14 PST Subject: How’s it going?

In general, Received headers are read from bottom to top (that is, mail originated from the bottom Received header and took the path outlined in each Received header above it), with the most recent one being stamped at the top and being the most reliable. In the above example, the message started from the IP 292.13.130.22 at Tony’s mail host. It was routed through my other friend bergie.net (IP = 267.99.33.167), then went through jd.net before finally arriving at its end destination in my inbox. It’s a complicated process but from the above, we can see that the message originated at 292.13.130.22, the first IP address. It’s a nice, handy way to trace the path an email followed.

Unfortunately, spammers will often insert fake routing information into the headers. Suppose that the email headers said the following:

From [email protected] Received: from mail.tony.net (mail.diamond-mail.net [292.13.130.22]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0); Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:36:15 PST Received: from frank (franksmail.net [284.33.167.99]); Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:35:35 PST Received: from mail.tony.net (mail.diamond-mail.net [262.13.130.22]) by mail.tzink.net (MyMailer 1.0); Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:31:15 PST From: Tony Diamond <[email protected]> To: Terry Zink <[email protected]> Date: Tue, Apr 7, 2010 14:36:14 PST Subject: How’s it going?

From here, we can see that the mail started out from Tony’s mail server, was relayed through Frank’s mail server and then routed through Tony’s (again?) before it came to me. While it’s odd that this double routing occurred, it is possible (though not probable).

The fact is that this message could have taken that path, or it could have originated at Frank’s machine. Frank could have inserted a fake Received header to make it look as if it started at Tony’s machine in order to trick the receiver into thinking it came from a trusted source. Without doing some manual inspection, it’s difficult to know programmatically where the message actually originated. Usually in the message headers there are some clues, but the fact is that the only Received header you can trust is the topmost one. (There are scenarios where you can trust lower Received headers, but those are outside the scope of this discussion.) That’s the one your receiving MTA stamps, and you can trust it to tell you where the message has come from.

Looking at parts of headers that are fake is one thing. However, it’s not enough simply to be able to distinguish between fake headers and real ones; we still need to be able to authenticate who the mail came from. In other words, while we certainly want to be able to tell when something is fake, we also want to know when something is real. If Tony sends me a letter, I might be able to tell from the handwriting that it doesn’t belong to him and therefore that the message is fake. But how would I be able to know if the message is real? Is there anything that we have in email that allows us to make that validation?

One of the simplest forms of authentication is Forward-Confirmed Reverse DNS – something that I call a weak form of authentication.

Now that we have seen how email headers are inserted by the receiving machine upon receipt of an email, we need to go into a little bit of detail about how mail servers convert IP addresses to host names and vice versa.

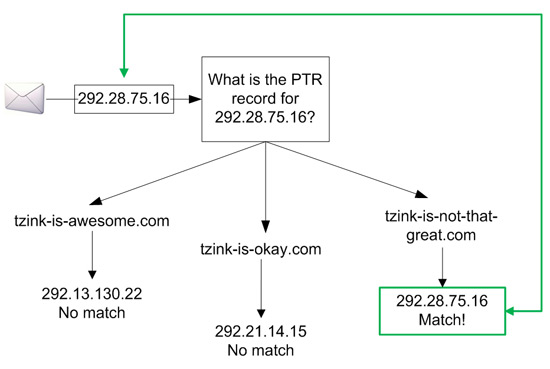

DNS stands for Domain Name System. It converts a host name to its IP address. Reverse DNS is the opposite: it converts an IP address to its host name. It does this by examining the IP’s PTR record:

A PTR record, or pointer record, maps an IPv4 address to the canonical name for that host. Setting up a PTR record for a hostname in the in-addr.arpa domain that corresponds to an IP address implements a reverse DNS lookup for that address. For example, at the time of writing, www.icann.net has the IP address 192.0.34.164, but a PTR record maps 164.34.0.192.in-addr.arpa to its canonical name, referrals.icann.org.

The converse of a PTR record is the A record, which maps a hostname to its 32-bit IP address. So, A-records are used for DNS lookups (example.com to xx.yy.zz.ww) and PTR records are used for reverse DNS lookups (xx.yy.zz.ww to example.com).

This brings us to Forward Confirmed Reverse DNS, or FCrDNS, which is when an IP has a forward DNS (name -> IP) and reverse DNS (IP -> name) that match (see http://www.answers.com/topic/forward-confirmed-reverse-dns). The process works as follows:

A reverse DNS lookup is performed on an IP. This returns a list of hostnames associated with that IP (the list could have 0, 1 or more entries).

For each entry in that list, a regular DNS lookup is performed to see if the IP matchup matches the original IP address. So, for example:

Since we matched the IP address in one of the domain’s A-records that was found in the PTR, we are said to have FCrDNS for the IP.

This is important in spam filtering because if an IP has FCrDNS then we can be sure that the mail originated at the domain. Spammers cannot normally forge this if they are sending from zombie computers.

So, for the following email that Tony has sent me:

The sending IP and the domain name match when we check them out in DNS. We have now confirmed that the IP and domain agree with each other in DNS. Because the owner of the IP and the domain are the only ones that can maintain the public records in DNS, we can be sure that the mail is coming from the owner of that IP and domain. Since Tony owns them I can be sure that the message came from Tony.

I call this a weak form of authentication for two reasons:

Authentication by FCrDNS is implicit, not explicit.

Yes, it’s nice if the A-record of the sending domain matches the PTR record of the sending IP. If the two of them match, then the chances are very high that the owner of the IP and domain are one and the same. We assume that is the way it is supposed to be, by design, but there’s no public documentation from the domain and IP owner saying that they set it up that way.

This works for small users that don’t control a lot of IP addresses, but not for big ones.

It doesn’t scale.

Often in legitimate circumstances, we just can’t get FCrDNS.

Let’s say I am a very large (fictitious) webmail provider, woohoo.com. If I send mail from [email protected], the sending IP of the MTA may not be in woohoo.com’s A-record. In fact, this is quite common. In order to scale to support millions of users, Woohoo has deliberately separated the hosting of its main page http://www.woohoo.com/ from its email servers. This is needed for redundancy; if the main page goes down it shouldn’t affect the mail servers, and vice versa.

If you receive an email from [email protected], it will always come from an IP in the range 257.17.0.0 – 257.17.255.255. If you get the A-record for woohoo.com, it will always fall in the range 257.16.0.0 – 257.16.255.255. They will never match.

What constitutes a match, anyhow? If [email protected] sends from IP 257.17.11.162:

A-record for woohoo.com – 257.16.18.48

PTR-record 257.17.11.162 – mail22.woohoo.com

Is this a match? It looks like it. But maybe not. Maybe woohoo.com doesn’t want anyone doing partial matches, it has to be a complete match. But part of woohoo.com is there - maybe we should use it? Should we authenticate implicitly? What sorts of risks do we open ourselves up to if we do? (A lot.)

Unfortunately, the idea of implicit authentication is a risk.

Forward-Reverse Confirmed DNS is simply too narrow a case to be used for authentication. For small senders who have narrow lists of IPs to maintain, it works. As an organization gets larger, it needs to find a solution that scales much better and authentication must be more explicit. We still want to authenticate an email, but we have to move onto something other than FCrDNS. To do that, we need to look at stronger authentication technologies – SPF, SenderID and DKIM. The discussion of those, however, will have to wait until next month.