2008-01-01

Abstract

Despite the best efforts of the IT security industry it looks like the malicious bot is here to stay. Andrei Gherman looks at how botnet monitoring can provide information about bots as well as helping to keep the threat under control.

Copyright © 2008 Virus Bulletin

The constant increase in the prevalence of bots over the past few years will not come as news to anyone. Bots have been analysed and studied thoroughly, command and control servers have been shut down, and authorities have begun hunting for those running such networks. Virtually every IT professional is aware of this threat, but despite our best efforts, it looks like the malicious bot is here to stay.

In the beginning, malware writers improved their bots constantly, adding new features and innovations with each version. Today, however, bots are mass-produced, with dozens of slight variations of old malware being released with countless methods of packing and encrypting. This makes the bot problem very difficult to control.

Although the anti-virus industry aims to combat new variants more effectively by developing and improving on heuristic detection, there remains a gap between the spreading and the detection of new variants. Honeypot technology has helped to shorten the time frame, but wouldn’t it be better if we could detect the new variants directly at their source?

This article provides more information about botnet monitoring and how it can help keep the threat under control. Some of the methods and techniques used in the Avira lab will be described, along with their advantages and disadvantages, concluding with the presentation of an automated tool capable of fulfilling various tasks.

Malicious bots have undoubtedly been the fastest growing threat over the last few years. Virtually unknown a few years ago, IRC bots have risen to become the most widespread malware type in the wild. Although nothing spectacular regarding IRC bots has happened for quite a while, the threat continues to exist and grow.

Prompted by the huge number of variants that continue to appear, and the fact that almost every malicious bot includes the functionality to download and execute files (most of the time in order to update itself or install spyware/adware), the Avira virus lab started the Active Botnet Monitor (ABM) project.

The original purpose of the project was to find a way of obtaining the download locations in order to analyse and, if necessary, combat the potentially malicious files before they become a widespread threat. Although this is still its main objective, the ABM project has proved to have several other uses, such as the collection and building of statistics relating to botnets’ size and location and highlighting the relationships between different threats.

The project began in 2005 and started a lot more slowly than we had anticipated. At the time, although botnets were a known and growing threat, useful documentation on the subject was not readily available. The first few months of research consisted of a long process of painstakingly reverse engineering countless variants of bots from several families in order to find out exactly how they worked and what kind of functionality they included.

Sometimes infected systems were allowed to stay connected to the command and control (C&C) servers for days (in a controlled environment, of course) and all the sniffed traffic was analysed manually. Before long the amount of raw traffic that was logged became too large to store, let alone analyse.

The obvious next step was to obtain the information needed to connect to a C&C server through the quick behavioural analysis of a bot and then use this information to connect to the server using some of the existing IRC clients. As we had expected, this approach failed and was quickly dismissed. The botnet controllers (sometimes bots themselves) could easily identify the popular IRC clients we used and sometimes we were denied access to the servers. Another problem was that as the number of bots grew, more and more instances of our IRC clients were needed. Obviously this was not a feasible solution and it became clear that we needed a specialized, purpose-built tool.

By this point it was obvious that the best (and probably only) way to gain access to the information we needed was to enter the botnet by pretending to be an infected system. Regardless of how this was achieved, the initial requirement for the botnet monitor was to be able to notice and log the URLs that appeared in the communication between the bot and the C&C server.

Before designing the system a second requirement was added, namely the ability to identify possible commands to join other channels and act accordingly in order to stay under the radar. This proved to be a very good idea, as it helped to mimic the malware’s behaviour accurately and also provided a way of obtaining additional information that was not available through monitoring only those channels that were hard-coded in the body of the bot.

For example, botnet controllers might become suspicious if one of their bots didn’t obey an obvious command. Furthermore, it was known that botnet herders sometimes prefer to organize their bots in several different channels, in order to provide more efficient control (especially concerning large botnets) or just to keep ‘back-ups’ of the bots on other channels in case the original channels are taken down by the authorities. Therefore, getting onto as many channels as possible (without raising the attacker’s suspicion) seemed like the right thing to do.

Our first idea was for the system to act as man-in-the-middle between a bot and its C&C server. Theoretically this was the best design as it meant that our tool could simulate an infected system’s behaviour perfectly.

Another advantage of this design was that it would be very easy to implement. All we would need to do in order to have a functional tool was build a general-purpose TCP client + server system which simply forwards everything it receives from one end to the other. It would be protocol-independent and, by analysing the actions of the bot on the simulated internet environment, we could obtain a lot of information easily. We would be able to follow everything the botnet did during its lifetime (downloading files, spam messages, DDoS targets, etc.) without the attacker ever finding out.

The problem with this type of system, however, is the complex infrastructure it requires. This design would have worked perfectly well if we had been planning to study just a few bots, but when trying to build a system that monitors a huge number of botnets continuously and indefinitely, the problem becomes obvious. There are simply not enough physical systems available to infect every time a new bot variant appears. Of course virtualization helps, but not nearly enough. An additional solution would be to try infecting a system with multiple bots. In theory, this might work (and our experiments showed that this could be done), but in some cases the results are likely to be unpredictable.

It became clear that the only reasonable way to infiltrate a botnet would be to implement our own IRC client. Of course, not all the IRC commands supported by the protocol would need to be implemented, just the ones that were useful for our research.

Initially we still wanted to mimic the malware’s behaviour perfectly, so we planned for our system to have a database containing a list of typical commands and the bot’s responses to those commands. However, that idea was never implemented. The variants appeared too quickly, one after the other, and analysing each and every one of them (to determine the full list of commands it accepted and how it replied to the operator) would have taken too long. Furthermore, as the source code for some of the most popular bots is freely available, it would take just a rename of some commands and a recompile to render our system useless.

So we decided on a different approach. Our bot would always remain ‘quiet’. It would never reply to any of the operator messages. Although we weren’t completely happy with this approach, and we feared we might easily be discovered, it turned out to be a lot more efficient than we had anticipated. First, this is because botnet operators have to deal with very large numbers of bots, and if sometimes one doesn’t reply it usually goes unnoticed. This is true even in cases where the botnet operator is a bot designed for this purpose. Furthermore, a bot’s failure to reply can be explained in several ways (e.g. lag, a bad connection, filtered traffic, lost packets, etc.), but a bot replying with a wrong message would surely tip off the attacker about our presence.

For similar reasons we decided that our system wouldn’t include an Auth/Ident server, even though we were well aware that some families of bots included this functionality. A missing Ident server could be explained by a blocked port or a failure to bind, whereas a different one would be suspicious.

In the end we decided to implement only the following commands in our client:

Commands needed to join the botnet:

PASS

NICK

USER

PONG

JOIN

MODE (not necessarily needed to join, but useful for simulating the malware’s behaviour)

Other commands:

NAMES (useful for statistics, it can also provide an almost fool-proof way of checking if our client is on a certain channel)

LIST (useful for statistics, also under certain circumstances it can provide a quick way of checking if a certain channel already exists on the monitored server)

Using this as a starting point we began implementing our client. Some additional requirements we had to take into consideration were that it had to be a multi-server application (obviously) and that it had to be an (almost) automated system that would require virtually no user interaction. The support for multiple servers was implemented using threads (not a very good idea when it comes to debugging, but the advantages this method provides over others far outweigh the inconvenience, especially when dealing with servers that are not RFC compliant).

In order to automate the system as far as possible the following behavioural pattern was established: first, the botnet monitor considers all the traffic with the server to be suspicious. In particular this means that, unlike some known malicious IRC bots, which parse only the messages that come as PRIVMSGs or NOTICEs, for example, our client tries to find possible commands in every piece of traffic that comes from the servers (PRIVMSGs, NOTICEs, topics, MOTDs – in practice it analyses everything that isn’t a PING).

After receiving a message, it starts parsing for URLs. If a string containing a URL is detected, it is logged automatically. Afterwards it starts parsing for possible commands to join other channels. If a word in the message fits the IRC format for channel names, it checks whether that channel exists on the server and then tries to join it. At first it tries without using any password. If that fails it then tries all the words received in the message as potential passwords (for a while we were afraid that this brute force attempt would be discovered, but so far this has not happened). Eventually the messages that don’t contain any URLs or ‘valid’ commands to join other channels are logged and stored for future analysis.

The system worked pretty well for most botnets regardless of the family to which they belong, the type and structure of commands they use or the functionality of the malicious bot. However, it did have some serious problems with the fact that some of the malicious servers were not RFC compliant. In some cases the problem was small and could easily be fixed, but that didn’t help much since for botnets fixing an RFC compliance problem means fixing it for a single server. Each non-compliant server had its own way of not following the standard. Some servers didn’t provide the numeric responses, others never sent PING messages, a few didn’t provide any responses at all, and there were even some cases where the IRC statements were slightly renamed in order to prevent unauthorized access. With every problem we fixed we drifted further away from the protocol we were originally trying to implement.

Eventually we had no choice but to learn to play the attackers’ game and use the IRC standard as just a guideline rather than a set of rules. At this point our client uses its own ‘universal’ protocol, which is based on IRC but quite different from the original. In our protocol the client has two statuses: ‘trying to connect’ and ‘connected’.

The ‘trying to connect’ status is more or less a typical session when a client tries to connect to an IRC server and/or join channels. The difference is that our client doesn’t expect the server to provide any useful information regarding the login process.

For example, a normal IRC login session would require (most of) the following steps:

PASS (if the server has a password)

NICK

USER

MODE (if the bot is known to set a certain user mode)

JOIN

The server would normally supply responses after each step, and in addition it would issue a PING after the NICK or the USER command (i.e. before the client logs in).

However, since we cannot rely on the server’s answers, our client just issues each of these commands one by one and waits for a certain length of time after each one. If the timeout expires and no message is received from the server, our client jumps to the next command in the sequence. If a message is received, the client checks if the message is a PING. If it is, it replies with the appropriate PONG and jumps to the next command, otherwise it waits for the timeout to expire again (waiting for the second time is necessary as some servers split what is normally a single message into multiple messages). Of course, during this process all messages that are not PING requests are analysed in order to capture any potentially suspicious information (for example in the MOTD or in any messages received before our client joins a channel).

During the time our client is ‘connected’ it listens, analyses messages and acts accordingly.

This method has proved to be very efficient when dealing with any type of IRC server (RFC compliant or not) and has been used successfully ever since its implementation.

Although catching potentially malicious URLs is still ABM’s main purpose, some additional functionality was implemented in order to provide a more comprehensive view of the botnet scene. The most interesting is ABM’s ability to write large amounts of information into a database, which allows us to compile statistics regarding the size and location of the botnets.

There are two ways to determine the size of a botnet. One is to count the distinct IP addresses of the users connected to a C&C server, and the other is to count the number of bots that are online at a certain time. However, neither of these options can provide a 100% accurate picture of the situation, as botnet controllers usually try to hide this information by configuring their servers so as not to disclose the IP addresses of their clients, or to provide fake or no data relating to the number of clients connected at a certain time.

Eventually we decided to implement both ways of obtaining this information, as we felt that although neither of them was accurate by itself, together they could provide a more complete picture of a botnet’s real size. If, for example, we decided to count only the distinct IPs, we could underestimate the real size, as it is possible (and very likely) for more computers in a network sharing the same external IP to be infected by the same bot. On the other hand, if we decided only to count the number of bots, we could overestimate the size of a botnet, as it is possible for the same infected system to be on different channels at the same time and we could mistakenly consider it to be multiple bots. Having the same information from two sources allowed us to be more confident that the conclusion we drew from analysing the statistics would be as accurate as possible.

During our research we monitored several thousand servers and channels and managed not only to obtain many new malware samples and bot variants, but also to find out some new information about botnets.

For example, during 2007 we monitored more than 7,000 channels on over 4,500 servers and obtained about 2,000 URLs hosting malicious samples. Furthermore, our database currently contains over 380,000 entries consisting of various communications between systems infected with malicious bots and C&C servers – information that will help us understand the threat and the attackers’ way of operating.

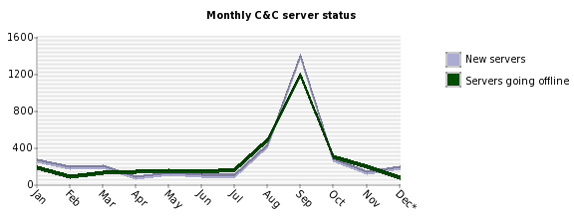

Figure 1. The number of new servers that appeared and the number of servers that went offline permanently each month (January – September 2007).

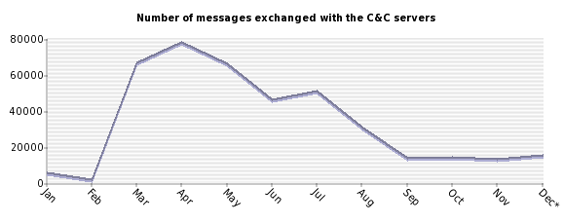

Figure 2. Monthly botnet activity measured in number of exchanged messages (January – September 2007).

A noteworthy aspect of these URLs is that in most cases they provide more than one sample. By monitoring these URLs over time we discovered that the file at that location usually changes, therefore each monitored URL gives us a chance to catch and detect several malware variants.

Besides this information we were also able to identify over 30,000 unique infected IPs and managed to estimate the total number of infected systems to be more than 200,000. Of course, these figures only apply to the monitored servers that allowed this information to be collected. In reality, the number of systems infected during 2007 will have been a lot greater.

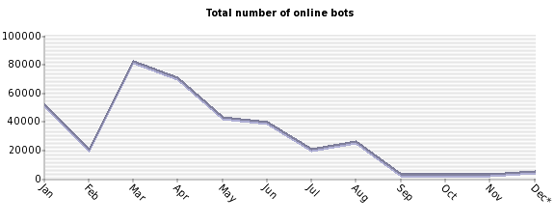

Figure 5. Monthly botnet activity measured in the estimated number of online bots (January – September 2007).

Another interesting aspect of our study is related to the localization of botnets. The country hosting the largest percentage of malicious C&C servers is the United States, with more than 43%, followed by Poland with 10%, Germany with 8% and Canada with 7%.

The situation for infected IPs is similar. The United States leads with 11%, followed by Germany with 9%, Poland with 7%, and Canada with 5%.

We must reiterate, however, that these figures only apply for the servers that allowed this information to be collected. The situation in reality may be quite different.

Monitoring is probably one of the best approaches possible when it comes to mitigating the botnet threat. We have come a long way since the beginning of the ABM project and discovered lots of interesting things, not to mention the malicious samples we have managed to catch and detect directly at the source.

Although the decline of the IRC bot is starting to become apparent, and IRC servers will probably be replaced by more sophisticated and harder to track C&C servers, for now the botnet problem is still far from being solved – if it can ever be. To date we have detected more than 100,000 individual malicious bots and this number is increasing on a daily basis. Furthermore, during 2007, between 10 and 20 new malicious botnets appeared each day. With these figures in mind I think we can safely say that, for now, we have not seen the last of the malicious botnets.