Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jan 17, 2019

This blog post was put together in collaboration with VB test engineers Adrian Luca and Ionuţ Răileanu.

In a talk I gave at IRISSCON last year (the video of which you will find at the bottom of this post), I discussed how spam is a problem that has almost been solved (and certainly has been well mitigated).

You would be forgiven for thinking that traditional spam is mostly a thing of the past. This isn't true: in our VBSpam lab, using the spam feeds provided by Abusix and Project Honey Pot, we see that spam messages are still sent out in their millions: Viagra spam, dating spam, spam offering SEO for your website and, recently, a lot of extortion scams where the victim is told that they must pay a few hundred dollars to save their browsing habits from being shared online.

In our lab, we measure how well such spam is blocked by email security products. For traditional spam messages, with very few exceptions, the block rates are extremely high – often only a small fraction below 100 per cent. However, things are different when it comes to emails with a malicious attachment or that contain a phishing link. It is not uncommon for an otherwise well-performing email security product to miss as much as ten per cent of these emails, and for individual emails to be missed by more than half of the products in our lab.

Such emails aren't inherently harder to block, but the fact that the cybercriminals behind such campaigns tend to be more skilled, and the fact that the emails are sent in much smaller batches, means that they are able to evade filters and blocklists more easily.

Below we list some recent examples of phishing and malware emails seen in our test lab, notable because they were missed by many email security products.

If you would like your product to be tested in our lab, to receive weekly updates on its performance and, optionally, be included in our quarterly public reports, please contact us at [email protected]!

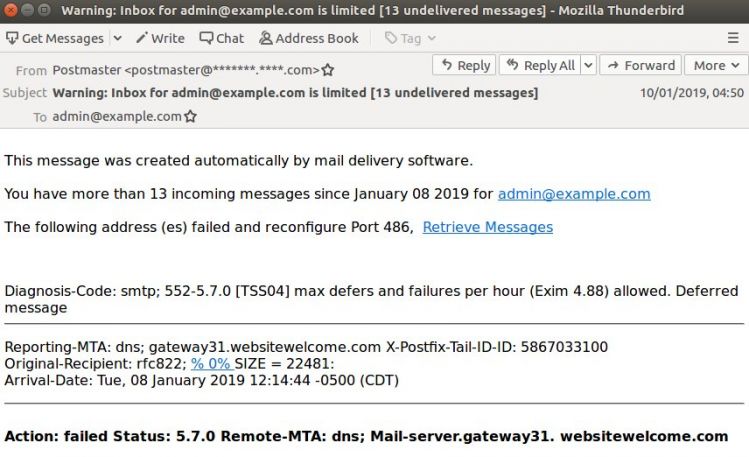

At first glance, a message "created automatically by mail delivery software" looks like a genuine bounce. It must have tricked products in our test lab too: only a handful of them blocked this email.

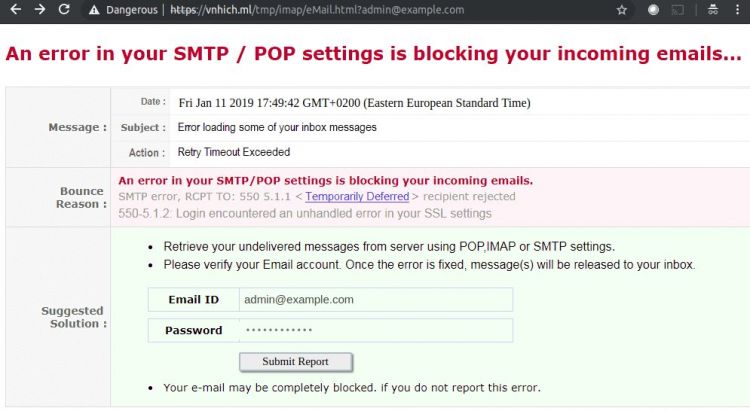

However, email bounces don't typically contain links. This one does, and indeed the link takes you to a phishing site that asks you to enter your email credentials. Interestingly, this template has been used previously in phishing campaigns.

The linked page looked like an ordinary phishing page, appearing legitimate to the untrained eye. But, to evade detection, the page (hosted on a hijacked Yoomla site) contained very little HTML code, and most of what appeared to be text was, in fact, part of the background image, displayed via CSS. Only the form was part of the HTML.

Luckily, VB also has a lab where we can check the ability of web security products to detect sites like these. Several days after the email was sent the site was still live, and although the majority of products detected it, some failed to block it.

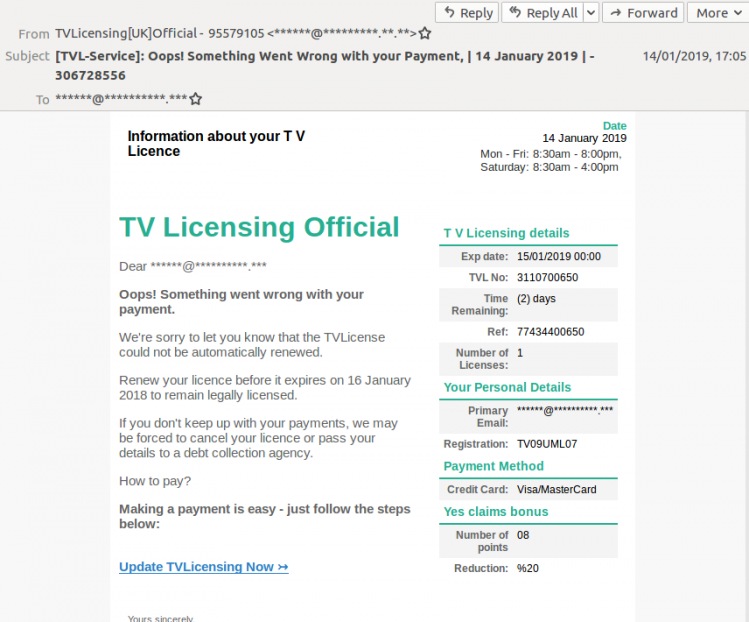

In the UK, the BBC is largely funded through TV licences that anyone watching TV at home must pay for; indeed, a Russian friend once asked me "is it true that in the UK, you need a government licence to watch TV?". Though the system appears slightly outdated (there is a discount for those who have only a black-and-white TV), fines are issued to those found watching TV without having paid for a licence.

Unsurprisingly then, TV licence phishing emails about failed payments have been around for quite some time. Malwarebytes' Chris Boyd wrote about a campaign in September last year. A new campaign was covered by Graham Cluley earlier this week.

We have recently seen a fairly large number of emails of this campaign in our lab. What concerned us, though, were the many products that missed the emails, with some of the earlier ones being missed by almost all products; block rates increased as the campaign progressed.

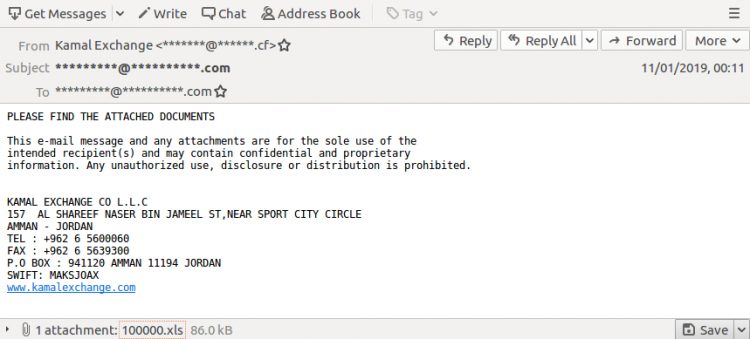

Apart from the fact that the recipient's email address is in the subject line, there is nothing suspicious about an email with "attached documents", especially if you were expecting someone to send you some files. The document in this case was a malicious Excel file (SHA256: 62706e2512e5a7f369730cce4ab45d70703c762d8eb6dba7148b8099f7c39fac) that, through macros, would run malware on the target's device.

We did not analyse the malware itself, but it is typical for there to be many potential payloads, depending on various characteristics of the victim.

What we found both interesting and worrying, though, was the fact that half a dozen products in our lab, as well as the majority of IP- and domain-blacklists, failed to block this email. This was no doubt thanks to a combination of the malicious code being obfuscated in the attachment and the fact that the email was sent from a legitimate, but likely compromised mail server.

Some emails are noticeable not because many products miss them, but because they are very unexpected. This was the case when we saw an email with the 2004 Mydoom worm as an attachment. The almost 15-year-old worm had already been reported as still being sent in spam attachments by Brad Duncan in December. In the samples he saw, the PE file was zipped, while we saw the PE file itself attached to an email (SHA256: b672583624d1ba9d2a75978643133117bfea5dab664f6d346293a3bc10658c14). This in part explains the high block rates: most products block such attachments before even scanning them.

We thought Mydoom's continued appearance and its upcoming 15th birthday a good resason to republish a 2004 article on the worm.

Spam may be what Bruce Schneier once described as "a rare success story" in the world of IT security, but the devil is in the details. And in these details, things don't always look as good. We will continue to look at spam from the angle of which emails manage to bypass filters; and we will regularly report the findings of our lab team on this blog.