Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jan 28, 2019

Over a one-week period earlier this month, the average email with a malicious attachment was almost three times as likely to bypass email security products than a spam email without such an attachment. When it came to phishing emails ─ a category in which we include emails that link to malware ─ the situation was even worse and such emails were more than 15 times as likely to be missed by security products.

There are two conclusions we can draw from this. The first is that malware and phishing campaigns are sent with more professionalism and in much smaller batches, which helps them bypass filters at a relatively high rate.

The second is that a malicious link is more effective for a spammer than a malicious attachment. Intuitively, this makes sense: though some products do scan links, this is less effective than scanning malicious content contained within the email itself, even if the attachment typically ends up downloading the next-stage payload from elsewhere.

Of course, a link inside an email creates a single point of failure, whereas a malicious attachment may include multiple ways to download the next-stage payload; hence, once it has made it to the inbox, an email with a malicious attachment could actually be more effective.

Emails used in Virus Bulletin's test lab are provided by Abusix and Project Honey Pot. Don't hesitate to contact us ([email protected]) if you'd like to have your product added to our tests.

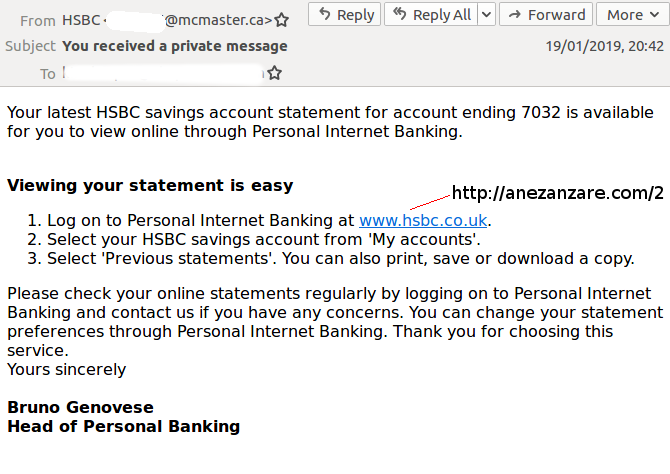

Only a few products in the lab successfully blocked an email about a private message from the HSBC bank, which led to a phishing page on a compromised website. (The phishing page had been taken down by the time of our analysis.) What may have tricked products is the fact that the email was sent from a compromised account at a Canadian university, thus bypassing any sender-based filters.

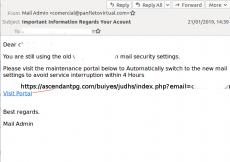

This explains why we also saw many generic phishing emails that used new mail settings or an about-to-be-deleted account as a lure to have a user enter their email credentials on a phishing page. Though most of these emails were blocked by all, or almost all products, some did slip through.

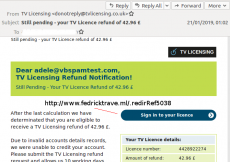

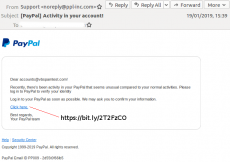

Other common phishing targets were tax revenue services, invoices (which typically link to malware), accounts at Netflix and Amazon, UK TV licences (as seen previously) and the most archetypal of all phishing targets, PayPal.

|

|

|

Malicious attachments come in various types, but the two most common are Office documents (using macros to run malicious code, or exploiting an Office vulnerability) and compressed archives. We have not noticed any attachment type that does a better job of bypassing email security products.

Though block rates of emails containing malware are significantly higher than those of phishing emails, it is not uncommon for such emails to bypass half a dozen security products or more.

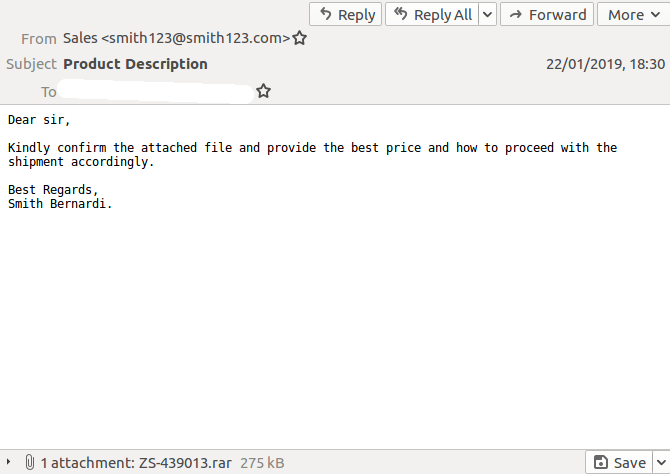

One notable recent example was an email about a product that likely appeared sufficiently generic not to raise any suspicion and that seemed relevant to most recipients.

Attached to the email was a rar archive which contained a single PE file (SHA256: 32af83660b7084ee03f66d1c3fdab337ea41eaf6a0cfd3ee320b0ed740ceb65d). Though we did not perform a thorough analysis, based on open source intelligence we believe it is probably Lokibot.

Extortion spam

While malware and phishing emails are sent in relatively small batches, this isn't the case for 'sextortion' spam emails, where the sender demands money in order not to release the recipient's secret browsing habits. Some of these emails include a password used by the account owner (and obtained from one of many public breaches) to make it more credible.

Last week, security journalist Brian Krebs wrote an interesting analysis of these campaigns, pointing to them using a weakness in GoDaddy and possibly other DNS providers that allows them to add DNS records.

We believe there are multiple active campaigns of this type and have also seen them in languages other than English. Indeed, we have observed the use of legitimate domains and likely compromised SPF records, but have not noticed particularly low block rates for these emails.

Ultimately, the first rule of sending spam applies: no matter how good your delivery mechanisms are, if you send unwanted emails in very large numbers, the overwhelming majority of them will be blocked.