Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jul 3, 2018

One of the most significant developments in the threat landscape in recent years has been the return of malicious Office macros, their resurgence having started four years ago.

Unlike their predecessors from the 1990s, these macros can't run automatically, but require the user to explicitly enable macros. This obviously mitigates the damage quite a bit, but not enough to stop this being an attractive infection method for both opportunistic and targeted malware attacks.

Since then, malware authors have been looking for other features that can be abused in a similar way. Last year, researchers at Sensepost discovered that the Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE) protocol could be used to deliver malware. Now, security researcher Matt Nelson has found another such method: the .SettingContent-ms filetype.

Introduced in Windows 10, these are XML files that are essentially shortcuts to the Windows Control Panel. However, Nelson found that they can also be used to run other commands, including PowerShell code. And thus they can be used to run or download malware.

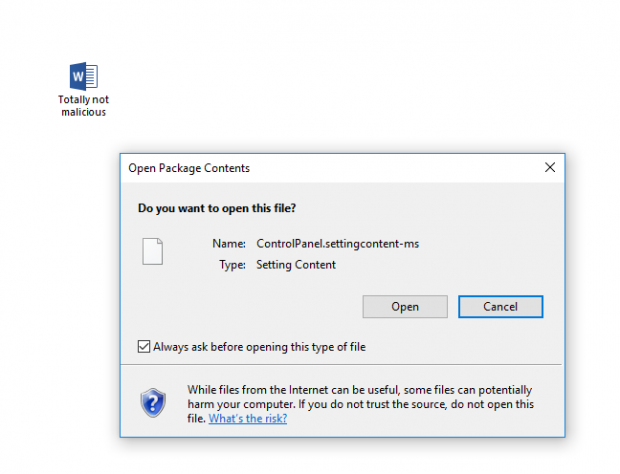

Because .SettingContent-ms files are not listed as known bad file types in Office, they can also be embedded into Office documents – when opened, all the user has to do is confirm they want to open the file and the device will be infected with malware. (When downloaded directly from the Internet, the files are run without any warning, but Nelson rightly believes that this is a less likely infection vector.)

The warning shown to the user when opening a .SettingContent-ms file embedded in an Office document. Source: Matt Nelson.

As per its recently published policy for patching and servicing, Microsoft has decided not to fix this issue, though of course this may change in the future; Microsoft did eventually disable DDE after it became a popular way for malware to spread.

As operating systems and software is becoming more secure, both malware authors and white hat researchers will increasingly be looking for exploitable features rather than bugs. Though some features can be disabled, if a user has the system privileges to perform an action, they can probably be socially engineered to do so.

One way to mitigate this risk is to harden systems by limiting the number of things a user can do. I have previously recommended the iPhone for high-risk users for this very reason.

The risk can also be mitigated by using security software. Though many security experts are rightly sceptical of the bold promises made in product marketing, there is no question that security software does a much better job than most users at deciding what programs and scripts should be allowed to run.

So far, there have been no reports of this technique being used in the wild. Several security vendors already claim that their product would block this kind of infection; if you work for a vendor, it might be a good idea to check whether yours does too.