Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jul 6, 2018

If, at some point in the past few years, you have looked at a spam campaign in which a lot of emails were being sent from Vietnam or India, there's a good chance the spam was sent by the Necurs botnet.

Necurs has been active for at least six years – Virus Bulletin published a three-part analysis of the botnet (1, 2, 3) by Peter Ferrie back in 2014 — and I have always found understanding Necurs to be very helpful in understanding the current threat landscape.

Necurs-infected machines tend to be older, and poorly protected. The botnet's rootkit doesn't support Windows 8 or newer – in fact, Necurs appears not to have infected any new machines in years, suggesting the infected machines have rather poor security hygiene, rarely if ever get cleaned and probably don't run up-to-date security software. For obvious reasons, poor security hygiene is more common in lower income countries, which explains the botnet's geographical spread.

Necurs is still very active though, despite its management apparently having changed at some time in 2016. Like many botnets, Necurs is modular and its operators are able to push out new modules through its C&C channel.

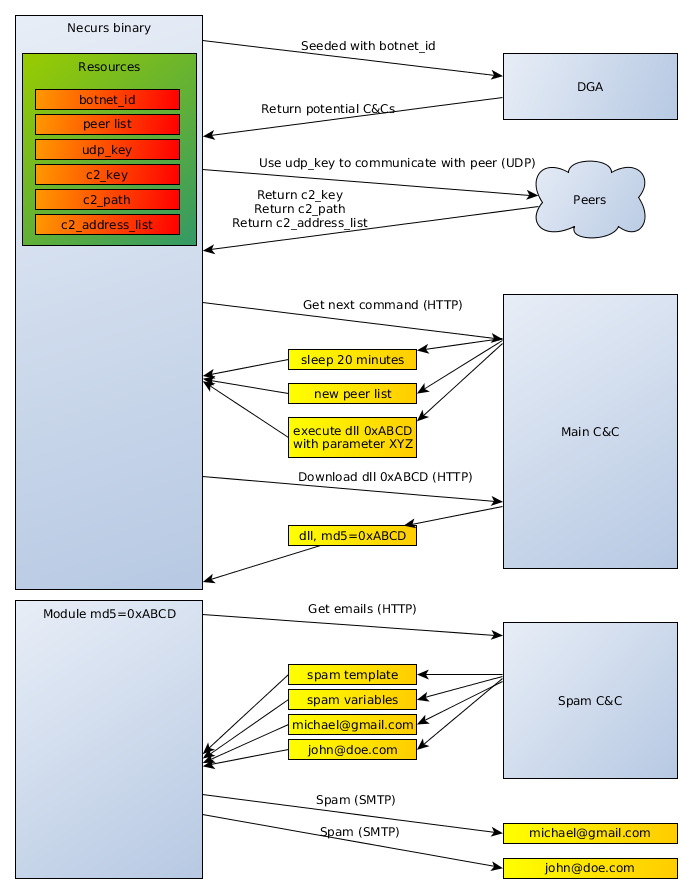

Necurs communication. From the VB2017 paper by Jarosław Jedynak & Maciej Kotowicz on spam botnets.

Necurs communication. From the VB2017 paper by Jarosław Jedynak & Maciej Kotowicz on spam botnets.

A recent Trend Micro blog post looks at modules that have recently been pushed out to the bots and how this has changed the botnet's behaviour. Though infamous for its spamming activities, Necurs is now used less for sending spam and more for mining cryptocurrencies (in particular Monero). This, of course, fits into a general trend of malware being used for cryptocurrencies, and makes particular sense if the machines are low value and there is an assumption that the owners wouldn't be willing, or able, to cough up the money demanded by a ransomware infection.

But that is not all of it. It turns out that some Necurs infected machines do live in more interesting environments. A module recently uploaded to the bots checks if the machine is running in an environment in which banking activity is taking place, or if the machine is used for point-of-sale activity or to trade in cryptocurrencies; in these cases, the Flawed Ammyy remote access trojan is pushed to the endpoints. (Flawed Ammyy was also spread via a recent Necurs spam campaign.)

A remote access trojan (RAT) gives the botnet operators full control over the infected machine and it is not hard to imagine how, in these particular cases, it can be used to make money directly from the infection.

Spam bots are relatively harmless for the owners of the infected devices and there isn't often a clear incentive to clean them up. Necurs' recent activity serves as a reminder that such an infection still means someone has access to the machine, which could suddenly be used for something far worse.

The decline in Necurs' spam-sending activities isn't necessarily good news for our ability to block malicious email traffic either: Necurs spam has always been easy to block, if only for the simple reason that residential IP addresses from Vietnam tend to be listed on almost every blocklist. Indeed, in recent months we have noticed a small deterioration in the ability of email security products to block malicious spam. Spammers looking for other botnets could have contributed to that.