Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jun 21, 2018

In email security circles, IPv6 is the elephant in the room.

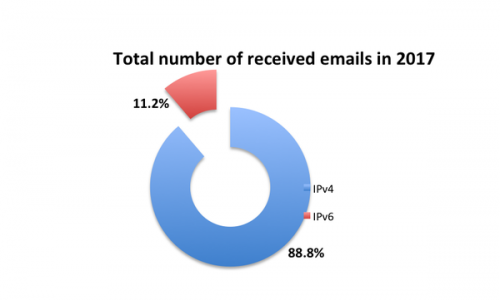

While the transition from IPv4 to IPv6 is a relatively smooth affair for most of the Internet, and few people will have noticed that a large part of Internet traffic is currently using IPv6, email is still lagging behind: RIPE, Europe's Regional Internet Registry, estimates that in 2017 only around one in nine emails was sent over IPv6.

Source: RIPE Labs

There are two reasons for this. The first is that, while the roughly three billion usable IPv4 addresses aren't sufficient for the current Internet, they provide more than enough IP addresses to serve the mail servers the Internet needs. There thus isn't a strong incentive to move to IPv6.

The second reason is that there actually is an incentive not to move to IPv6: spam. In particular, the fact that IP-based blacklists play an essential role in just about every anti-spam solution, often as a means to weed out the bulk of botnet spam before the content of the emails are analysed.

Though it is technically possible to run IPv6-based blacklists, and some such lists do exist, the practically infinite address space makes these lists far more difficult to run, while spammers could easily choose new address ranges for every new campaign – something which on IPv4 is simply not possible.

So should we just stop using IPv6 for sending email?

While indeed the need to move to IPv6 isn't very urgent for email, we can actually use this as an opportunity. Google, for instance, requires those sending emails to have a valid PTR record for the sending IP address, and for the email to pass at least one of SPF and/or DKIM.

These are reasonable requirements, and ones that legitimate email can be expected to fulfil, even if, for reasons of backwards compatibility, not all of them do. Spammers typically can't fulfil these requirements without more or less identifying themselves, thus making it easier for their emails to be blocked.

This doesn't mean that by moving to IPv6 we can solve spam (which is a feature of, and not a bug in, the way email works), but I don't think the often expressed fears about being unable to handle it are justified.

In an IPv6-only email world, things will certainly be different. Filtering will rely less on IP-based blocklists, but DNS-based lists of IP addresses and especially domains may actually start playing an even more fundamental role, even if this role may become less about the instant blocking of emails, and more about helping to build a holistic picture of whether an email is legitimate or not.

In particular, this makes such lists more useful in blocking targeted email attacks, whose small scale often allows them to fly below the radar of blacklists, but where properties of the domain (such as its registration date, or its past email history) can actually help spot them. We are certainly seeing a trend towards more of these kinds of email attacks.

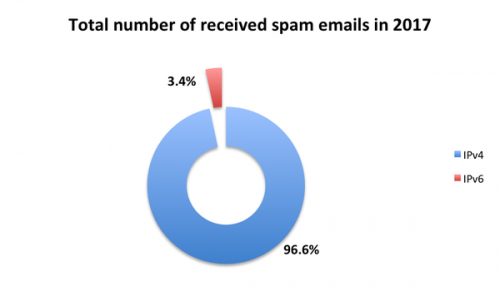

So far, not a lot of spam is being sent via IPv6 – a little more than one in 30 spam emails according to RIPE – and anecdotal evidence suggests that most of this is incidental: spam sent from bots that just happen to run on IPv6-connected devices and using software that is agnostic to the IP version.

|

Source: RIPE Labs

I don't expect this number to grow any time soon. But if it did, we'd be more ready for it than we may realise.