Posted by Martijn Grooten on Mar 6, 2018

Sending one email is easy. Sending thousands or millions of emails is hard: one effect of the anti-spam infrastructure we have collectively built is that the process of sending email scales very badly (even for those who only send legitimate messages). This is why companies tend to outsource their mail delivery operations to email service providers (ESPs) – these handle unsubscribe requests, bounces, and deal with the occasional but inevitable listing of the mail servers on DNS blacklists.

In the main, these ESPs manage to avoid having spammers as their customers, but occasionally spammers find a backdoor into an ESP's systems. Recently, one of the largest ESPs, Mailchimp, was found to have been used in this way: My Online Security wrote about it yesterday, while Libra Esva covered the subject in January.

It is unclear how spammers managed to gain access to Mailchimp's systems; possibilities range from a vulnerable third-party plug-in that integrates into Mailchimp, to a vulnerability in Mailchimp itself, or customer credentials being stolen through a phishing attack.

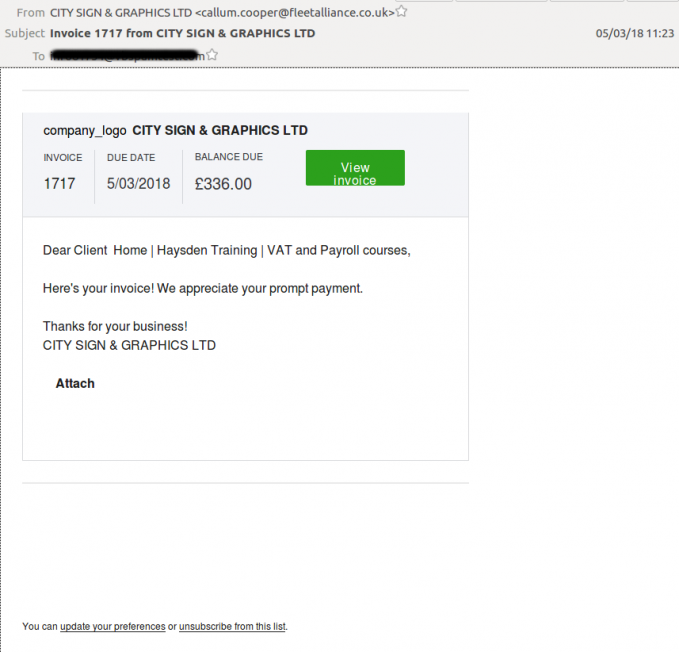

The latest campaign sent emails claiming to link either to an invoice or a fax. In theory, this makes an email harder to block than if an attachment had been present, as email security products scan attachments, but typically avoid inspecting links beyond the URL.

In practice, while some email security products in our test lab did indeed miss the emails, the majority correctly marked them as unwanted. And even in cases where users did receive and open the email, they would have had to download the attachment in order for the payload to be executed. When I tried to do so, the URL was blocked by Google Chrome, and when I managed to bypass that detection, the payload turned out to have been removed from the (compromised) website. Even if successfully downloaded, the malware still would have had to bypass an endpoint security product.

Pulling off a successful malware campaign is a lot harder than it may seem. This is why malicious spam campaigns – still one of the most common ways for malware to spread – rely on very large numbers to begin with. Being able to break one part of the 'kill chain', for example by using the servers of a legitimate mailer, does pay off, but most users would still be protected against the attacks.