Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jan 5, 2018

At one end of the attack spectrum there are attacks that cleverly exploit features of modern processors. At the other end, there are tech support scams that, through some basic social engineering, aim to convince the victim that their PC is infected (or even that their 'IP address is spreading viruses') and then charge a hefty fee for 'fixing' it.

To give an idea of the kind of users targeted by this threat, I've spoken to support scammers that didn't ask whether I was using a Windows or a Mac (they follow different scripts for different operating systems) but tried to determine this themselves through a series of questions ('what do you see there on the screen?', 'what happens when you press this key?', etc.).

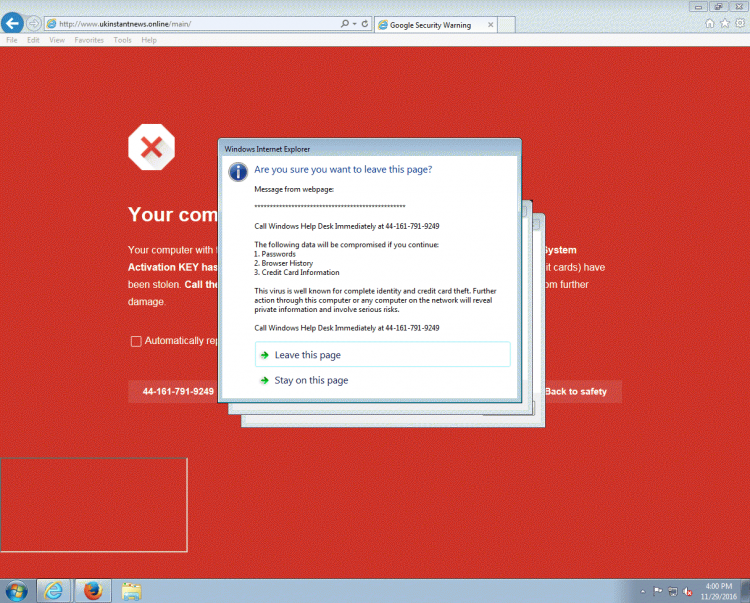

These days, rather than cold calling potential victims, most scammers use exploit kits and malvertising to give the victim the impression that there is a serious problem with their computer, after which they may call the phone number that is, conveniently, displayed on the screen.

But cold calling still happens, as Symantec's Andrew Brandt (a VB2017 speaker) found out last week. Many security researchers like to play dumb when receiving such a call and there are many humorous videos of scammers being scammed, but these calls also provide an opportunity to investigate what is going on. Based on my own experience, the following is some advice on how a researcher can get the most out of a cold call.

The first thing to note is that scammers tend to work like telemarketers. Once they believe you are a potential victim, they are happy to accommodate your wishes – for example by calling back at later time, that is more convenience for you. You can use this opportunity to prepare a virtual machine and recording equipment.

You may want to make your machine look quite real, though I've never witnessed a scammer being suspicious of what looks like a brand new machine. Spending a few minutes browsing the Internet may generate some (harmless) errors and warnings in the logs, which may help the scammer: these logs are often used as 'evidence' that there is a problem with the PC.

I have never seen any evidence of support spammers engaging in other kinds of malicious activities, such as stealing documents, but it may not hurt to add some 'bugs' (such as the free ones from Thinkst Canary) to Word documents and PDFs, in case these documents are siphoned out and later opened.

Once the scammers believe they have convinced you that your IP address is indeed spreading viruses, they will demand payment before any further action is taken. Not a lot of research has been done on this second phase, but it is worth trying to see if you can get there.

I have succeeded twice: once by using a made-up credit card number that, with some luck, had a valid check-sum (this is, of course, something you can prepare in advance). Another time, I used social engineering myself to get the scammer to agree to let me pay later as 'I had left my credit card at work'.

After I had played the satisfied customer – even one they didn't make any money from – the scammers would call back regularly, either to let me know that my one-year support licence was due to expire, or to inform me about new problems with my PC. It was a nice side project, and when I moved house I was disappointed that I had to give up my phone number which had become a scammers' honeypot.

One thing that helped was providing the scammers with a fake first name (they had my last name and phone number from the UK electoral register), so that I always knew when scammers were calling me – no one else would ask for 'Mr John'.

Finally, some people believe in wasting the scammers' time by dragging out the conversation for as long as possible. I am sceptical of this strategy, if only because the scammers' income tends to be an order of magnitude below that of the minimum wage in most western countries.

Some of my experiences in dealing with support scammers were presented in a VB2012 paper (pdf) that was co-written with David Harley (ESET), Steve Burn (Malwarebytes), and Craig Johnston. A VB2014 paper by Malwarebytes researchers Jérôme Segura remains, in my opinion, the best overview of the subject. Jérôme continues to write about the subject on Malwarebytes' blog.