Posted by Martijn Grooten on Sep 18, 2017

For the security community, 2017 might well be called the year of the update: two of the biggest security stories – the WannaCry outbreak and the Equifax breach – involved organizations being hit badly as a consequence of not having installed (security) updates, while another major story, that of (Not)Petya, concerned a threat that spread through a compromised update system used by the Ukrainian tax software MEDoc.

A new story can now be added to the latter category: that of CCleaner, a legitimate tool widely used for cleaning up Windows and OS X computers. Researchers from Cisco Talos found a version of the product that came with a malicious payload added to it, which installed a backdoor on targeted systems.

In a blog post, the Cisco researchers provide a good overview of the malware and its C&C communication to a hard-coded IP address, with a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) as a backup communication channel. The takedown of the C&C servers and the takeover of the relevant domains means that the original malware itself has now been neutralized. However, should the attackers have used the backdoor as a foothold to install more persistent malware on an infected machine, this malware would likely still be active.

It is unclear whether this has happened, and there is no evidence to suggest that it did. But it is not beyond the realms of possibility that the attackers had specific targets in mind when they spread the malware; this would explain why it exfiltrated information about the infected machine.

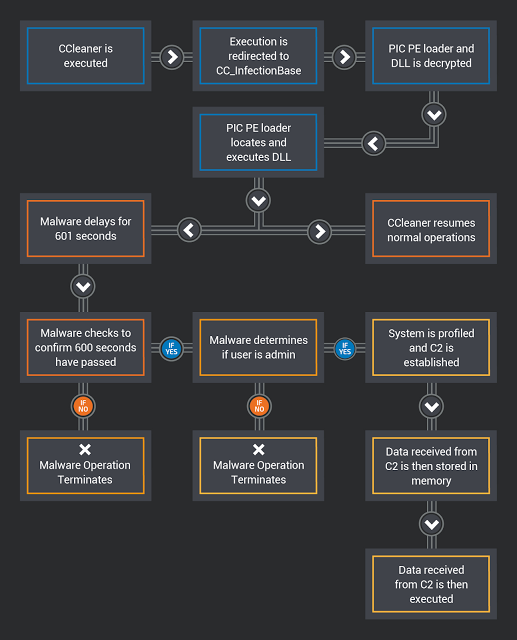

The malware operation process flow. Source: Cisco.

In an announcement, Piriform, the company that produces CCleaner, played down the seriousness of the issue, saying that only a small percentage of its users would have downloaded the malicious version (the product did not install automatic updates). This is true, as is the fact that the only data known to have been exfiltrated from infected machines was "non-sensitive", but it remains important for infected users to follow the advice from Cisco: reinstall machines or roll back to a previous version.

It is easy to pick on Piriform and Avast (which acquired the company less than two months ago) for this serious issue, but it may be more helpful to look at the bigger picture: both Piriform and MEDoc are small companies. Without knowing anything about the inner workings of either company, it would be reasonable to assume that the security strategy of each was reflective of their respective size, rather than of the much larger footprint they had in the global IT infrastructure. This is a big challenge, not just for companies in a similar position, but for the security community as a whole.

(Thanks to Cisco's Warren Mercer for confirming a few details. He and his colleague Paul Rascagnères will be speaking at VB2017 in Madrid in two weeks' time - registration is still open!)