Posted by Martijn Grooten on Jun 29, 2017

"What's in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet"

Shakespeare's philosophising can equally be applied to malware, and whether you call it Petya, NotPetya, Nyetya or Petna, the latest piece of malware to hit the headlines is just as damaging.

The name isn't the only thing security experts disagree on when it comes to the malware that has been causing damage around the world (and seems to have hit Ukraine particularly hard) in the past 48 hours.

What experts do agree on is that it shares some similarities with the ransomware known as Petya (a February 2017 analysis from Fortinet's Raul Alvarez includes, for example, the same fake CHKDSK screen as we see in this malware); that at least one of the infection vectors was the compromised update mechanism of MEDoc, tax accounting software for the Ukrainian market (as explained in a Microsoft blog post); that it uses a number of methods to spread internally within networks, including but not limited to two SMB exploits leaked by the 'Shadow Brokers' (as explained in a Cisco Talos blog post); and that, as Kaspersky researchers explain, it uses a randomly generated string installation ID that a victim, upon payment of the ransom, is supposed to use to get the decryption key.

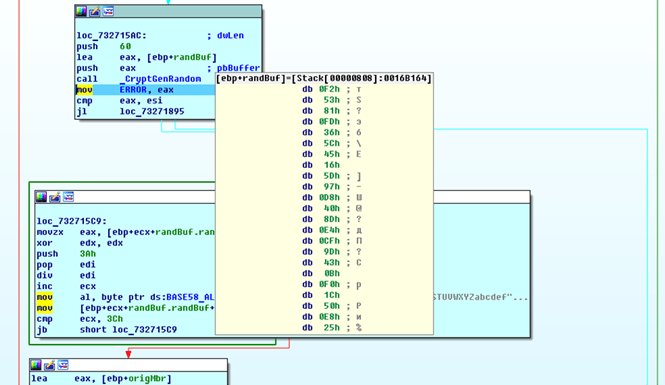

The malware's use of GetCryptRandom to generate the installation ID; source: Kaspersky.

The malware's use of GetCryptRandom to generate the installation ID; source: Kaspersky.

However, the use of a random string, rather than something that leads to the private encryption key used to encrypt the files on the machine, means that it is likely that decryption of files won't be possible, and that those who have paid the ransom to the hard-coded Bitcoin address will get neither their money nor their files back. Therefore, it won't make much of a difference that email provider Posteo has taken the somewhat odd step of blocking the email address that victims were supposed to use to receive the decryption key.

Of course, it could well be that the lack of an encryption mechanism was intentional, and that the authors didn't mean to gain financially, just to disrupt systems – and many people have jumped to quick, but understandable conclusions about who could want to do this to Ukraine.

We should be wary of confirmation bias though. In March, when the Shadow Brokers leaked a number of exploits against Windows vulnerabilities, the timing (it was a Friday afternoon) and the suspected motive of this group led people to believe that these were zero-day vulnerabilities. Indeed, several researchers confirmed the exploits worked against fully patched Windows systems and those who couldn't get them to work were looking at what mistakes they could have made. Later, it turned out that the first group of researchers were so eager to prove that these were zero-days, that they didn't realise their systems weren't fully up-to-date and that a recent Microsoft patch had indeed patched the vulnerabilities.

Malware written to destruct does exist and in recent years has affected, for example, South Korea and the Middle East. But malware authors do make mistakes and sometimes their mistakes are indeed odd and unusual. Without further evidence to the contrary, we should keep that possibility in mind.

On the subject of encryption mistakes in malware, at VB2016 last year, Check Point researchers Yaniv Balmas and Ben Herzog presented the paper "Great Crypto Failures". You can read their paper here or here (PDF) or watch their presentation below.