Posted by Virus Bulletin on Sep 20, 2013

After initial takedown, more efforts put into making new fake accounts look genuine.

Virus Bulletin's research into a scam selling fake Twitter accounts being passed off as 'followers' has helped in the takedown of more than 45,000 such accounts - but has also showed that the scammers are upping their game.

The success of a social media account can be measured by the number of followers it attracts. It seems obvious that this doesn't work the other way: an account won't become more successful if it simply buys a bunch of followers. Yet the shady corners of the Internet are rife with sites that let you 'boost your reputation' by buying followers.

Although potential buyers are made to believe that the followers are genuine Twitter users, they are not. They are fake accounts, managed by the scammers who make a serious effort to make them appear real.

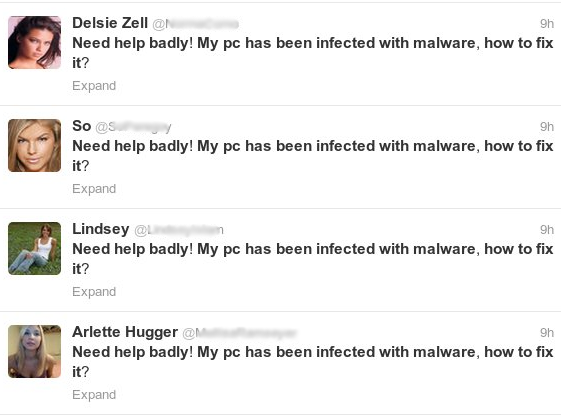

I stumbled upon one such campaign last month. It started with a question posed on Twitter about many users posting exactly the same Tweet about an apparent malware infection on their PC.

It didn't take long to figure out that these accounts had done little more than post random remarks and half-witty quotes - and that the same Tweets has been sent by many different accounts. There were many other similarities between the accounts, such as the lack of interaction or followers. The Tweets could usually be traced back to other prominent Twitter accounts.

The accounts 'followed' few other Twitter accounts, if any, but those that they did follow were shared by many of them. These were likely users that had fallen for the buy-followers scam. Indeed, the number of followers these accounts boasted seemed unreasonably high, given the content of the Tweets and the fame (or lack thereof) of the user.

There were a number of other characteristics that made the fake accounts relatively easy to spot. Using Twitter's public API, I wrote a script that searched for such accounts and it didn't take long before I had found more than 17,000 of them. I reported them to Twitter, which took prompt action and suspended them.

I suspected these were far from all of the accounts the scammers used: some of them were registered as early as September last year and many accounts had been dormant for long periods of time. Twitter's API only helped me find recently active accounts.

Indeed, some small modifications to my script allowed it to pick up many accounts that I hadn't seen before. I also noticed that new accounts were still being registered.

Possibly as a response to the mass-takedown, the scammers had upped their game and increased their efforts to make the accounts look genuine. Now they weren't just following those that had paid for them - they were also following each other, as well as several popular Twitter users. The Tweets posted by some of the newer accounts even seemed to be somewhat related to each other and included links and hashtags.

In fact, looking at these accounts on their own, there is very little that gives rise to suspicion. Only after noticing a number similarities with many other accounts can one conclude that these are indeed part of the scam.

The script helped me find at least 28,000 other fake accounts that were part of the same scam, around 30% of which had already been suspended by Twitter. The rest have since been reported to Twitter, which once again acted quickly.

Of course, from a security point of view, fake followers do little harm to the millions of genuine Twitter users. However, the longer they stay active, the less they will be noticed as fake. And it won't take much for their owners to turn them into a Twitter botnet sending malicious links - as other Twitter spammers are currently doing.

There are probably millions of fake Twitter accounts, many of which are engaging in all kinds of badness. Twitter tends to respond quickly to reports of any form of misuse, and users' ability to report accounts for spam works well. But when such an effort is being made to make the accounts look genuine, the company's task to keep its network clean will not be an easy one.

Many thanks to Bart Blaze for his help and suggestions.

Posted on 20 September 2013 by Martijn Grooten